Aperture introduces you to intent architecture (Intents)

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Aperture introduces you to intent architecture (Intents)

Besides rhetoric, what functions and features should an intent-based solution actually have?

Author: Aperture Finance

This is the first article in Aperture Finance's series on decrypting the Intents space. In this piece, we introduce the narrative around intents and how they address current challenges in DeFi, with a focus on Aperture’s role as a leading project in intent-based architecture. Whether you're new to the concept of intents or already familiar with products like Anoma and reports from Binance Research, Paradigm, and Delphi Digital, this article offers valuable insights for investors and practitioners alike.

Starting With Simple Scenarios

Imagine a future user experience enabled by Aperture, where users can clearly specify their desired final state from a transaction—and receive optimal solutions through a bidding mechanism:

● Hedge 50% of the volatility risk of my ETH holdings for 30 days, using any method, as long as the cost is capped at an annualized rate of no more than 2% per ETH;

● Claim all eligible airdrop rewards on my behalf, with fees not exceeding 1% (including gas costs);

● Rebalance my liquidity positions across all chains and DEXs (Uniswap, Maverick, and Sushiswap), ensuring 60% of funds are allocated to the pool with the highest APR, 30% to the second-highest, and 10% to the third-highest.

Under today’s “transaction-centric” model, each of these intents could spawn an entirely new protocol—from fundraising and development to community building. But developing a separate protocol for every use case would be far too time-consuming. Moreover, users remain constrained by front-ends and smart contracts. There is a better solution—but first, we must move beyond the transaction-centric paradigm.

Intent > Transaction

In today’s DeFi landscape, users rely on a well-known but limited “transactional approach” to achieve desired outcomes: interacting with dApp interfaces, triggering actions, and hoping for the best. This process mirrors challenges in healthcare systems—patients face endless choices, aiming for specific health goals, yet receive no guarantees on outcomes or even final costs.

Consider a simple example: Xiao Wang suffers from neck pain and has the following goals:

● Reduce overall pain by 40% to 100%;

● Spend less than $500 out-of-pocket;

● Achieve relief within three months.

Similar to browsing on-chain solutions, Xiao Wang might jump straight to considering surgery—an option limited by his own knowledge. He may consult a surgeon who claims the procedure will relieve his pain and cost under $500. Yet, the outcome often falls short: little pain reduction and actual expenses far exceeding $500.

In contrast, an “intent-based” system could revolutionize this process. In the same scenario, the patient could express their needs directly in natural language:

“Reduce neck pain by at least 40% within three months for under $500, prioritizing pain reduction, then cost, then time. Healthcare providers must have a 99% trust rating. Any treatment channel is acceptable.”

Suppose there exists an intent-based healthcare platform that enables competing healthcare providers (“solvers”) to propose optimal solutions. These solvers could differentiate themselves through technical innovation, novel therapies, or more competitive pricing.

Ultimately, Xiao Wang might receive a superior solution: a two-month treatment program from a provider with a 100% trust rating—daily sauna sessions plus biweekly rehabilitation therapy—reducing his pain by 90% at a total cost of under $200. (This article does not constitute medical advice; please consult a doctor for neck pain.)

Of course, this analogy has limitations—healthcare inherently involves unpredictability. Costs and timelines can be estimated, but individual outcomes vary widely. However, in our blockchain world, the situation is different: advanced process simulation, zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs), and other technological advances free DeFi users from such uncertainty.

So, what conditions are required to make intent-based systems a reality? Beyond theory, what functional features must intent solutions actually possess?

Core Components of Intent Architecture

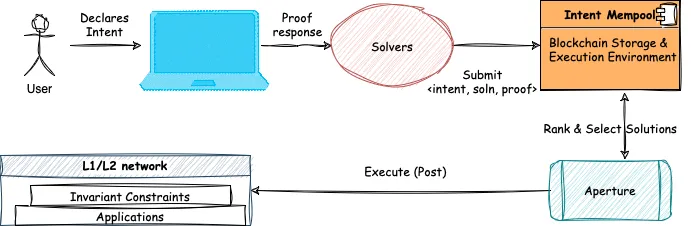

From the end-user perspective, a truly intent-based user experience (Intents UX) requires three key components—most of which are currently absent in existing DeFi dApps (at the execution layer):

1. A new type of user interface that allows users to explicitly state their transaction goals. Instead of being presented with binary “yes/no” options, users can clearly describe their desired end state.

2. A solver network that competes to identify and deliver the optimal way to achieve the user’s goal flexibly.

3. An arbiter executor capable of accurately ranking proposed solutions from various solvers and executing the selected final solution. The solver network is responsible for selecting the winning solution based on rankings, ensuring solver accountability and enabling transaction execution across dApps and blockchains (“global composability”).

Creating a new user interface requires a domain-specific language (DSL) that front-ends can use to translate intents into verifiable, on-chain executable formats. Establishing a solver network is essential to drive competition, delivering better rates and outcomes for users.

Beyond these user-facing elements, any intent architecture must abstract away certain complexities from the user, including:

1. Verifiability (Global Composability): The architecture must have a method to verify that a proposed solution truly fulfills the user’s intent. Standardizing verification is key to unlocking true “global composability.” In other words, if there’s a standardized way for an arbiter executor to verify final states—regardless of chain or dApp—users gain access to a genuinely globally composable intent network.

2. Ranking (Zero-Knowledge Proofs): Beyond cross-chain and cross-dApp verification, simulations and solution ranking are needed. Some verification processes may be too complex or costly for on-chain execution. Here, zero-knowledge proofs (ZK) can reduce computational overhead. Such ZK solutions don’t need to be built from scratch—modular tools like Axiom or Brevis can be leveraged.

3. Privacy (Privileged Solvers): Certain intents may expose sensitive user information (e.g., vulnerability to frontrunning). A robust intent architecture can address this by enabling privileged solvers. These solvers are specifically authorized to handle privacy-sensitive intents, possessing special credentials that allow them to manage transactions requiring higher security and confidentiality.

4. Solver Behavior Deviating From Intent (Penalty Mechanisms): To ensure solvers fulfill transactions as expected and avoid malicious behavior, the system must implement penalty mechanisms. A core feature of intent architecture is enforceable accountability—should malicious actions occur (e.g., transaction reversals or other attacks), the architecture has the authority to penalize such behavior. This protects transaction integrity and deters potential misconduct through solver penalties.

Aperture’s Universal Intent Architecture

Returning to our earlier example:

Rebalance my liquidity positions across all chains and all DEXs (Uniswap, Maverick, and Sushiswap), so that 60% of funds are concentrated in the pool with the highest APR, 30% in the second-highest, and 10% in the third-highest.

This describes a universal intent spanning all chains and DEXs. In the next article, we will elaborate on Aperture’s ambitious vision for the intent space: a network of Solver DAOs empowered by a unified interface. In subsequent pieces, we’ll analyze Aperture’s 2024 roadmap, detailing how we plan to go from blueprint to reality, step by step, in building a universal intent architecture. Stay tuned!

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News