From the Perspectives of UniSwapX and AA: Analyzing the Implementation Challenges of "Intent-Centric" Architectures

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

From the Perspectives of UniSwapX and AA: Analyzing the Implementation Challenges of "Intent-Centric" Architectures

What is "intent"? What are its applications?

Author: Shisijun

Recently, in Paradigm's article "Intent-Based Architectures and Their Risks," a prominent Web3 venture capital firm, "intent-centric protocols and infrastructure" ranked first among ten major trends in the crypto space. Combined with projects like Bob the Solver, Anomo, and DappOs showcased at ETHCC in Paris—projects that have been developing and exploring for years—this has sparked significant industry attention toward intent-centric architectures. The core goal of such systems is to dramatically enhance user experience by completely abstracting away complex transaction details, making it a potential engine for mainstream Web3 adoption.

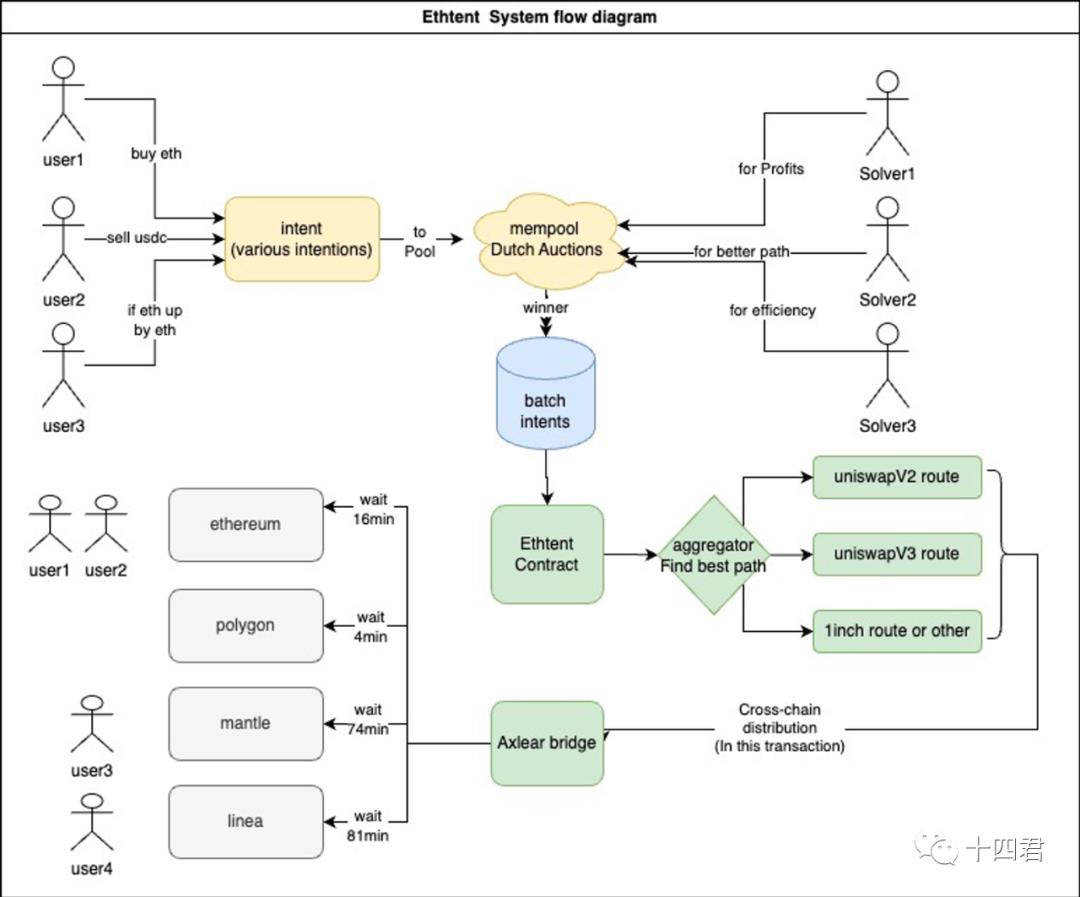

During this year’s Token2049 hackathon, I collaborated with the Card3 team (a B2B-focused NFT product offering high-ROI real-life social experiences) to build Ethtent, which secured second place in the DeFi track based on intent-driven design. This article will explore intent-centric architecture from my firsthand experience implementing a solver, as well as through two real-world applications: ERC4337 and UniswapX.

We’ll examine: What exactly is “intent”? Is it truly as promising as it seems? What are its applications? And what challenges remain for widespread adoption?

1. What Is Intent-Centric Architecture?

Just as account abstraction predates Ethereum itself, the earliest concrete concept of “intent” can be traced back to 2018, when the DEX Wyvern Protocol introduced its design philosophy. At its core, unlike traditional transaction models focused on execution steps, ordinary users primarily care about achieving accurate and consistent outcomes—not rigid adherence to process.

Let’s consider a scenario where you want to swap a certain token.

-

In traditional transactions: You must execute three separate transactions—deposit ETH for gas, approve token spending, then submit the swap transaction;

-

In intent-based transactions: You simply sign once: “I’m willing to exchange X amount of Token A for as much Y Token as possible, quickly, allowing up to 1% fee.”

We can understand an intent-centric protocol as a set of signed contracts enabling users to outsource transaction execution to third parties without relinquishing full control over their transactions.

Users only need to express their desired outcome—their intent—and one signature completes everything.

In other words: Transaction = how you do it; Intent = what you want, regardless of how it’s achieved.

Drawing parallels with the evolution of traditional internet services—from what providers offered, to matching supply and demand, to intelligent platforms—we see a similar trajectory over two decades of internet development:

-

Early vertical services (various portals where users search for numbers or workers to buy services);

-

Mid-stage service aggregation platforms (e.g., 58.com, matching service providers with user needs via traffic aggregation);

-

Later-stage intelligent platforms (algorithm-driven matching and recommendations enhancing intent accuracy, e.g., DiDi cross-city ridesharing, customized services).

Indeed, the intent-centric concept is compelling, and Web2 history confirms it as a key path to expanding user bases. But is it really that ideal? Let’s start by examining current market applications.

2. Typical Applications of Intent-Centric Systems

Although the intent-centric concept is newly gaining traction, numerous projects already align with it—or were inherently built around user intent. As Bastian Wetzel outlines in his article “Intent-Based Architectures and Projects Experimenting with Them,” various mainstream projects fall into this category.

As shown below, many protocols aren’t general-purpose intent solutions but rather specific ones—like Uniswap and Seaport. This mirrors Web2, where successful vertical solutions represent a necessary stage in intent-centric evolution.

ERC-4337 serves as foundational infrastructure supporting intent execution, reducing reliance on user-held gas thanks to bundlers.

Our main focus, however, remains evaluating whether these projects’ business models sufficiently support intent adoption. In my view, the most advanced real-world implementations today are UniswapX’s transaction intent model and ERC4337 as essential intent infrastructure.

2.1 Understanding Intent-Centric Design via UniswapX Economics

Shortly after UniswapX launched, I participated as both a Filler and quote provider in its RFQ system. It stands out as one of the most viable intent implementations because it directly and maturely addresses the economic incentives for counterparties—an essential hurdle for intent adoption.

2.1.1 Why Was UniswapX Needed?

Summarizing Uniswap V1–V3 development, AMM protocols historically faced issues including high user costs, poor execution prices, inefficient routing, suboptimal liquidity provider incentives, and more. Today, MEV dominates the mempool: nearly every large swap faces frontrunning, resulting in users getting the worst possible price while MEV extractors capture the profits.

UniswapX aims to tackle these problems head-on by fundamentally changing the AMM settlement mechanism—a strategic shift designed to disrupt the status quo.

Further Reading: UniswapX Research Report (Part 1): Tracing V1–V3 Evolution, Interpreting Next-Gen DEX Innovation and Challenges

2.1.2 What Is UniswapX?

By definition: UniswapX is a new permissionless, open-source (GPL), auction-based routing protocol for trading across AMMs and other liquidity sources.

Broadly speaking, there are three main models for Web3 trading markets beyond AMM:

-

On-chain order book: matching and settlement occur fully on-chain. Further reading: [Contract Analysis] CryptoPunks: The World’s First Decentralized NFT Marketplace

-

Off-chain order book with on-chain settlement: matching happens off-chain, final settlement on-chain. Further reading: X2Y2 NFT Market System Architecture

UniswapX shifts from the AMM model used in Uniswap V1–V3 to an off-chain matching, on-chain settlement order book model.

2.1.3 How Does UniswapX Work?

From the user perspective, suppose you wish to trade ETH ⇄ USDT around $1900 (allowing 2% slippage). All you need to do is:

-

Set your order parameters, including price decay curve and time limit (e.g., exchange 1 ETH for between 1950 and 1850 USDT within 24 hours);

-

Sign the order and publish it to the order book cluster;

-

Wait for a Filler to discover and fulfill your order.

That’s all the user needs to do.

From the Filler’s perspective, they are active executors of user orders—service providers with ample capital, cross-chain expertise, and comprehensive monitoring of all pools across chains. Their responsibilities include:

-

Scanning pools across protocols to gather real-time data needed for pricing;

-

Monitoring the mempool to anticipate future price movements;

-

Querying the RFQ network to obtain priority execution rights via quotes;

-

Analyzing public order books to determine optimal execution paths;

-

Competing in auctions when profitability thresholds are met (in Dutch auctions, later submission means lower final price);

-

Assessing other Fillers’ bid floors to strategically undercut them—even accepting lower per-trade profit—to win more volume overall.

So why would someone become a Filler? This brings us back to UniswapX’s economic model.

2.1.4 Evaluating UniswapX’s Intent Design

The key challenge for intent adoption is incentivizing users to publish intents.

Many limitations that previously disadvantaged DEXs against CEXs—such as transaction costs, MEV, slippage, routing inefficiencies, and impermanent loss—are now being addressed by specialized Fillers competing against MEV actors. Through technical superiority, they gradually reclaim value for users, creating a positive feedback loop (more users → more Fillers → more fee distribution).

Moreover, complex tasks like split-order routing are offloaded to backend systems. Users act solely as clients submitting orders, freed from worrying about execution complexity.

Thus, it forms a healthy economic cycle—both sides benefit—and sustainable incentive alignment ensures practical viability.

2.2 Viewing Intent-Centric Through ERC4337

At the bottom of the earlier diagram lies the Account Abstraction (AA) layer. For systems like UniswapX, since transactions are submitted by Fillers, users can naturally perform gasless cross-chain trades.

However, throughout the full transaction lifecycle, users still need to initiate an approve transaction authorizing UniswapX’s contract to deduct funds. To achieve truly pure intent-based transactions (no user-initiated transactions at all), integration with ERC4337 and Paymaster designs becomes essential.

For prior coverage on ERC4337—its definition, implementation principles, and evolution—see Shisijun’s previous livestream and summary: Explaining Account Abstraction in One Hour

In short, ERC4337 is an infrastructure stack:

-

On-chain, the EntryPoint contract verifies user signatures for authentication, ultimately driving the user’s CA wallet as identity;

-

Off-chain, users sign UserOperations as instructions, relayed through Bundler networks, which batch and submit them to chain.

The core optimization enables highly customizable CA wallets—supporting features like social recovery, project-funded gas, or using USDT as gas payment.

Today, however, we’re analyzing ERC4337’s value for intent from a business model perspective.

Recall why we praised UniswapX’s business model: both parties (user and Filler) gain value, with only MEV losing out. Yet relying on fees to ensure counterparty incentives is just one approach. Most future intent applications may instead generate revenue through B2B sales or consumer subscriptions, where intent fulfillment is just one component of a broader service offering.

Take payment systems like WeChat Pay or Alipay—they don’t charge consumers on peer-to-peer transfers but take ~0.6% when merchants withdraw funds (which also covers underlying transaction costs).

Over the past decade of mobile internet competition, maximizing user base was prioritized over immediate monetization, with revenue loops established later.

In the future, more dApps will emerge, and to improve user experience, many will gladly provide gasless infrastructure—just as Lens Protocol subsidizes hundreds of thousands of dollars weekly in Polygon gas fees to nurture content ecosystems. Compared to the millions burned daily during ride-hailing wars, this is still negligible.

Therefore, the most standardized, universal, and trustworthy gas sponsorship mechanism will inevitably be the paymaster system built atop ERC4337 (evolving from meta-transactions but surpassing them).

A special smart contract account, a Paymaster can pay gas for others. It performs validation logic per transaction and checks conditions. For example, within the ‘validatePaymasterUserOp’ method, it checks for sufficient approved ERC-20 balance, then uses ‘transferFrom’ in the ‘postOp’ call to collect it. (See referenced Bilibili livestream for detailed execution walkthrough.)

Overall, this offers a far more generalized gasless solution than meta-transactions—avoiding non-standard chaos and backward compatibility issues (meta-transactions require contract modifications).

3. Challenges Facing Intent Adoption

To summarize, intent-centric architecture holds great promise and represents a critical direction for ongoing development. Beyond business model hurdles, what technical obstacles stand in the way of real-world deployment?

3.1 Conflict with AI Integration

While some believe AI-powered intent parsing enhances UX, my background in security strategy taught me that explainability and reproducibility are paramount when applying AI in decision-making systems. For instance, if an account is banned without clear justification, handling user appeals becomes impossible. Similarly, financial systems prioritize stability and consistency above all. No institution can guarantee AI won’t act maliciously once granted asset control.

Hence, AI will likely remain an auxiliary tool for intent interpretation for the foreseeable future. On-chain data analysis requires deep understanding of blockchain mechanics—otherwise false positives are inevitable.

Further Reading: Deep Dive into EVM: Risks Behind Contract Classification

3.2 DoS Risks and Solver Matching in IntentPool

IntentPool, analogous to ERC4337’s mempool, presents another major bottleneck. IntentPool cannot reuse existing Ethereum client (Geth, Erigon) mempool mechanisms and must be independently constructed.

Even referencing ERC4337’s BundlerPool, mempool designs come with trade-offs:

-

Decentralized mempool: Suffers from propagation issues. Since executing intents is profitable, nodes running intent pools have incentives not to broadcast them, reducing competition.

-

Centralized mempool: Solves propagation but introduces risks of centralized auditing and manipulation.

In short, designing a discovery and matching mechanism that balances incentives with decentralization is extremely challenging.

3.3 Intent Privacy Risks

Signatures are irrevocable. Even with expiration timestamps embedded, canceling before expiry remains costly (each cancellation requires an on-chain transaction).

This has led to emerging standards aiming to standardize and protect intent privacy, such as Anomo.

Privacy protection is difficult to achieve within EVM systems, prompting cutting-edge work on private intent languages like Juvix—designed for privacy-preserving dApps. Juvix compiles to WASM or circuits via VampIR, enabling private execution on Anoma or Taiga-compatible chains like Ethereum.

4. Conclusion

It’s encouraging to see growing interest in intent-centric concepts. Finally, Web3 is moving beyond self-referential hype and tackling real barriers to mainstream adoption. Only by focusing on genuine user needs—rather than grand narratives—and humbly serving users can Web3 earn broad acceptance.

Future intent models will either follow UniswapX’s path—generating revenue via fees to subsidize counterparty incentives—or adopt tiered user structures: a few paying premium users alongside a large base of non-paying yet ecosystem-critical users.

Ultimately, intent isn’t about chasing the buzzword—it’s about improving product experience.

DeFi will be the first arena where intent shines. Over 20 DeFi protocols are already collaborating with DappOS. Brink Trade has developed an Intent Engine allowing Bridge, Swap, and Transfer operations to be bundled into a single signed intent. Additionally, established protocols like CowSwap, 1inch, Uniswap, and LlamaSwap continue expanding functionality to accommodate broader user intents.

At this year’s Token2049 hackathon, my team tackled a cross-chain swap + strategy-assisted dollar-cost averaging use case in the DeFi track (see Ethtent system diagram below).

One realizes that building vertical intent solutions for fixed needs atop existing EVM infrastructure isn’t hard. The true challenge lies in creating a marketplace—or collaborative framework—for intent solvers: enabling different solvers to compose, reuse, and standardize solutions while aligning economic incentives.

Standardization often requires top-down definition. Currently, DappOs and Anomo lead this frontier—promising developments worth watching.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News