Rollup Economics 2.0: Analyzing Multi-Layer Economic Relationships in a Mature Rollup Ecosystem

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Rollup Economics 2.0: Analyzing Multi-Layer Economic Relationships in a Mature Rollup Ecosystem

An obvious fact is that Rollups will eventually choose to adopt shared services, whether as part of a Rollup coalition or as part of an economic alliance.

Author: davidecrapis.eth

Translation: TechFlow

In February 2022, Barnabé proposed a rollup economics framework for resource pricing and value flows, designed to analyze key concepts such as MEV in L1-dependent economies, interactions between L1 and L2 fees, operator revenue and costs. It was a simple framework suited for a simpler world: centralized rollups running on independent training wheels. Over the past 18 months, much has changed: shared sequencing, decentralization, proof/data aggregation, rollup coalitions, governance.

We propose a new framework that will help make sense of the new world that rollups are preparing to scale into. There is still extensive experimentation underway, but several patterns have already emerged. We will analyze these key patterns and aim to provide a tool to understand where things might be headed and answer current open questions.

Back to Basics: Revisiting Rollup Economics 1.0

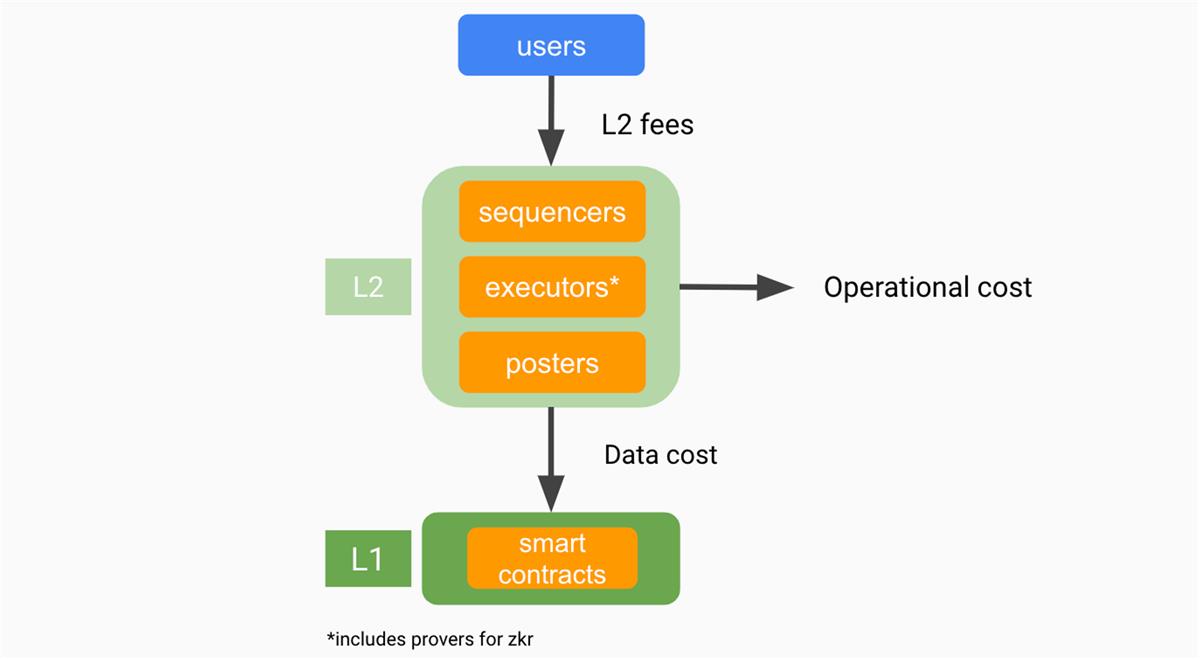

The original rollup economics framework included three entities: users, rollup operators, and the base layer. It also featured a similarly simplified view of value flows: L2 fees and MEV, operator costs, and data publication costs. This is a simple framework, but it's useful to start here and build upon it because things quickly become more interesting and complex.

From these basic flows, we can measure rollup protocol surplus and reason about related concepts—MEV extraction and distribution, L2 issuance, allocation of L2 congestion fees, and the time horizon over which a rollup maintains budget balance or achieves surplus (L2 ecosystems are growing economies, and running a surplus may prove useful for funding public goods, development, and growth within the community).

Rollup Protocol Surplus = L2 Fees - Operating Costs - Data Costs

The rollup protocol controls its L2 fees (including congestion pricing and MEV) as well as operating costs (including issuance and operator rewards). Regardless of whether the protocol aims for balance or surplus, L2 operations require coordination mechanisms to:

(1) optimally set L2 congestion fees,

(2) extract and redistribute MEV,

(3) reduce data costs through optimization and strategic publishing.

These are the main economic design choices currently being experimented with across different L2 ecosystems. In the future, protocols might reduce uncertainty in data costs by using blockspace derivatives.

One major change has occurred over the past 18 months. Similar to L1 block building, we’ve seen rollup operators being broken down into more specialized roles. As the economy grows, specialization naturally emerges—and this is good, because separation of concerns leads to more resilient systems, provided we can address it in our designs. However, the design space is now larger, so we need a new map to guide us.

Rollups Are Maturing

As rollups mature, their complexity increases—we call this phenomenon "rollup coalitions." Shared rollup architectures among similar types of rollups are designed to increase security (through shared governance and community coordination), efficiency (via shared functions and economies of scale), and user experience (through better interoperability and reduced fragmentation). At the same time, independent providers are developing infrastructure offering one or more of these benefits to any rollup choosing their services. We’ll detail these models below.

Independent Rollups

Individual rollups are moving away from training wheels, increasing both security and decentralization. From an operational/economic perspective, the primary cost areas include:

-

Sequencing: This incurs operational and incentive costs to motivate sequencers.

-

Data Availability (DA): Rollups must publish data on the base layer, incurring data costs—the main cost item discussed in the original framework.

-

State Verification (SV): For zkRollups, this directly increases operating costs via proof generation.

Across all these cost domains, individual rollups face important trade-offs between security and efficiency. For example, they may choose a less secure but cheaper data availability layer. Historically, data publishing costs (which we refer to simply as data costs, though they include some L1 computational costs related to publication) have been the highest line item. With the upcoming implementation of EIP-4844 on Ethereum and full Danksharding later, this will significantly decrease, providing rollups with the cost-efficiency needed to scale and support new use cases. In the long run, data costs and service efficiency could be further optimized through off-chain aggregation innovations that unlock economies of scale.

Concrete examples of aggregation include: shared sequencing services; for optimistic rollups, a promising idea is shared batch posting, enabling faster compression gains—especially for smaller players—offering lower costs and higher security through faster data publication; for zk rollups, shared provers are among the most exciting solutions, particularly since they allow recursive aggregation, yielding massive gains in efficient use of L1 data markets at the expense of increased off-chain computation. It’s clear that rollups will eventually adopt shared services, either as part of a rollup coalition or an economic alliance.

One potential direction for rollup ecosystems is having more independently operated rollups closely aligned with the L1. Though few implementations exist yet, at least two interesting architectures are emerging. One involves rollups delegating block sequencing to the L1, leveraging the L1 transaction supply network for MEV extraction while retaining control over setting L2 congestion fees. An even more extreme version sees rollups embedded directly into Ethereum itself. We’ll explore the economics of these models in greater depth when discussing MEV resilience and decentralization in rollups.

Rollup Cooperatives

The first type of integration between two rollups is purely economic cooperation—for example, economic cooperatives.

“A cooperative is a group of entities sharing or working together toward a common goal, such as economic benefit or savings.” — Wikipedia

In its simplest form, there is a joint procurement agreement among rollups for a certain service. Imagine a shared batch posting service that rollups can subscribe to, gaining lower data publishing costs. Deeper economic integrations are also possible—for instance, a shared sequencing service offering not only cost efficiencies but also enabling atomic settlement of transactions across rollups, thus lowering trade barriers between them. This model resembles the European Economic Community or other similar common market associations.

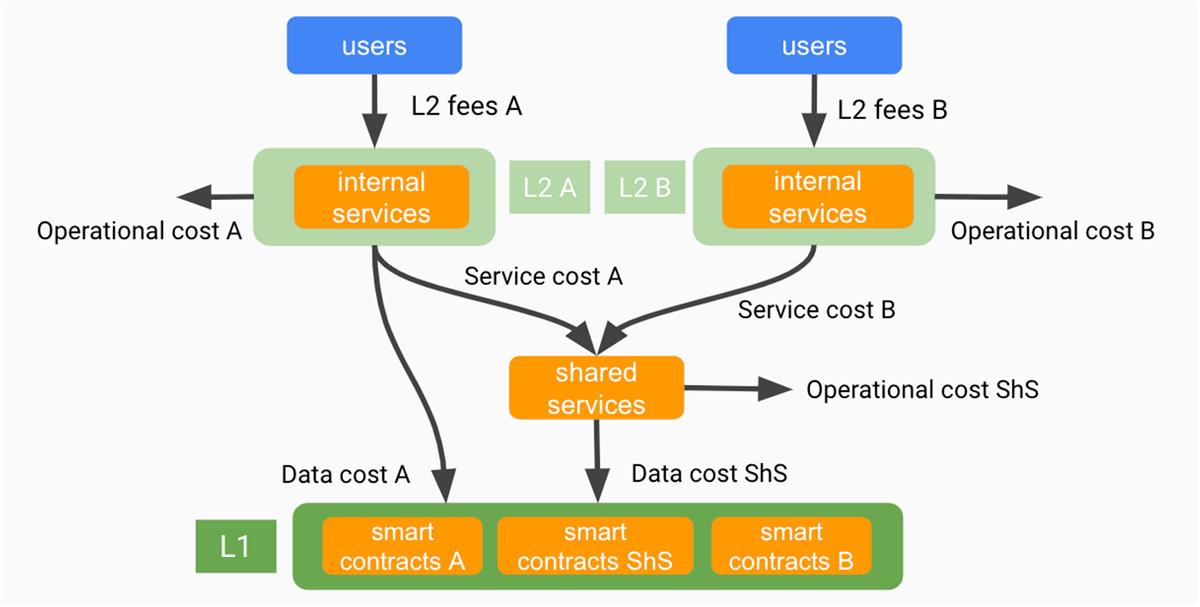

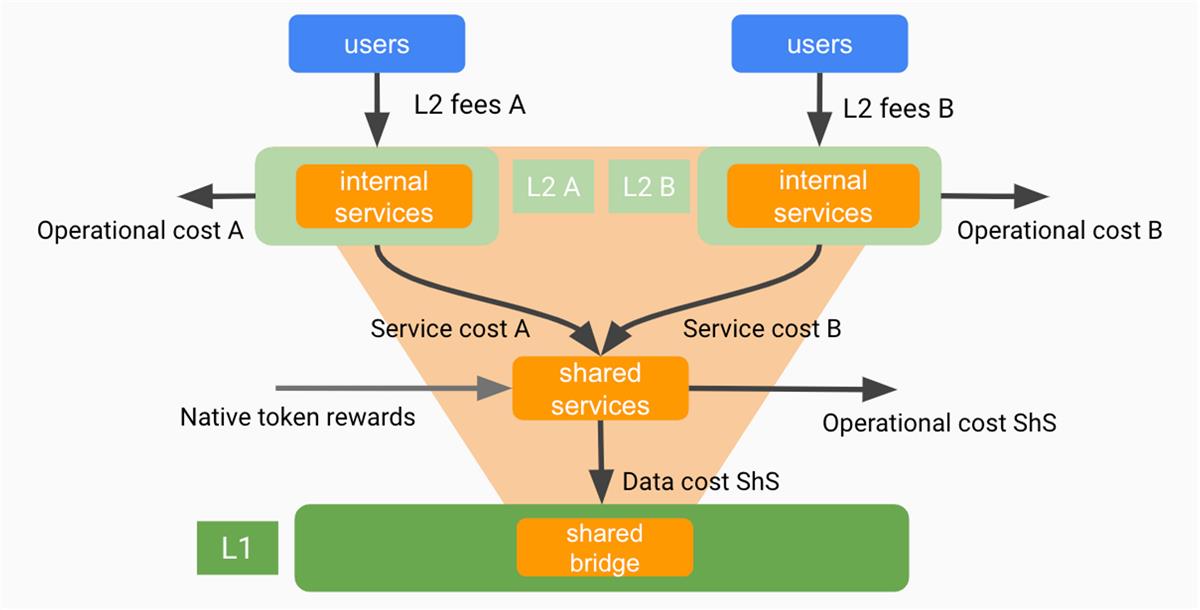

We can enhance the simple model of independent rollup economics by introducing intermediary service providers. In this case, two new economic effects emerge for the rollup ecosystem:

-

Rollup Cost Structure: Rollup operator costs now include operating costs, service fees, and data publishing costs.

-

Economics of Shared Services: The new entity must achieve budget balance.

Examples of such services include Espresso Sequencer, a shared service for sequencing and publishing limited to shared batch posting, or shared proving. In all cases, shared services raise two critical economic issues:

-

Cost Sharing of Services Across L2s: The total service cost must be allocated among adopting rollups in an economically sound and fair manner.

-

Decentralization of Shared Services: Achieving an appropriate degree of decentralization depending on the service type, balancing performance and robustness. This standard is lower than that of the base layer, but still involves managing incentives and MEV.

Rollup Coalitions

Rollup coalitions differ from economic cooperatives because they feature both economic integration and some form of political integration. This model resembles a federal state.

Technically, political integration is achieved through a shared bridge, but it also requires a shared governance system. Here, we largely set aside political and governance considerations and assume the existence of a shared bridge, focusing instead on the implied economic relationships. This federated rollup architecture is emerging across all major rollup systems, which are becoming platforms for deploying interoperable peer rollups.

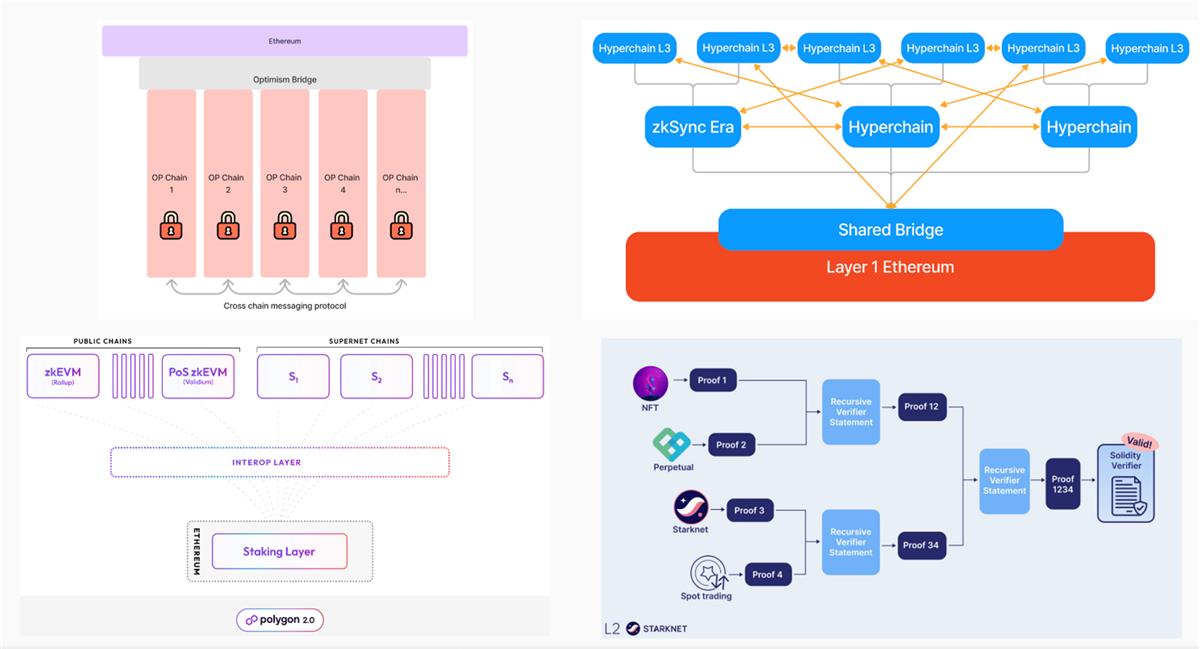

For example, Optimism Superchain, Polygon 2.0, StarkWare SHARP, zkSync Hyperchains, and other related projects share similar patterns in their architectures. We generalize this in the diagram below. Note that for clarity, we make the realistic assumption that rollup coalitions automatically opt into shared services and do not incur direct data publishing costs.

The presence of a shared bridge introduces additional economic variables. In particular, native L2 tokens—such as the OP token in the Optimism ecosystem—provide significant decision-making power through governance over resource allocation, roles, and economic flows within the ecosystem (for example, OP governance is an experiment in hybrid token-based identity governance). Once rollup tech stacks mature and primary security issues are resolved, the next focus becomes robustness, which may involve some level of decentralization.

When rollups consider building decentralized services (for sequencing, proving, or validation), they will need to run consensus protocols. This is when large-scale ecosystems see opportunities to "upgrade" their native tokens into productive assets (exactly what Polygon 2.0 plans to do with POL). This isn't the only way to decentralize L2 services, as Ethereum L1 can also leverage its superior security properties. However, for larger ecosystems wishing to retain more internal control/governance and associated rewards/incentives, using native tokens may be an attractive path.

Native tokens are crucial economic tools for bootstrapping L2 ecosystems/economies. Issuance can reward service operators, fund ecosystem support programs, or finance public goods. However, when native tokens back decentralization via a native staking protocol, excessive dilution may reduce security. Even if used solely for governance, excessive dilution could lead budget-constrained holders to sell, potentially causing ownership concentration. Therefore, it seems vital to have a token issuance schedule aligned with demand growth. Finally, another key consideration is increasing the L2 economy’s dependence on its native token (rather than ETH), which reduces resilience to certain failure modes, as fallback to L1 may no longer be viable. In the extreme, the L2 remains secured by Ethereum but loses the safety net provided by Ethereum’s external monetary backing.

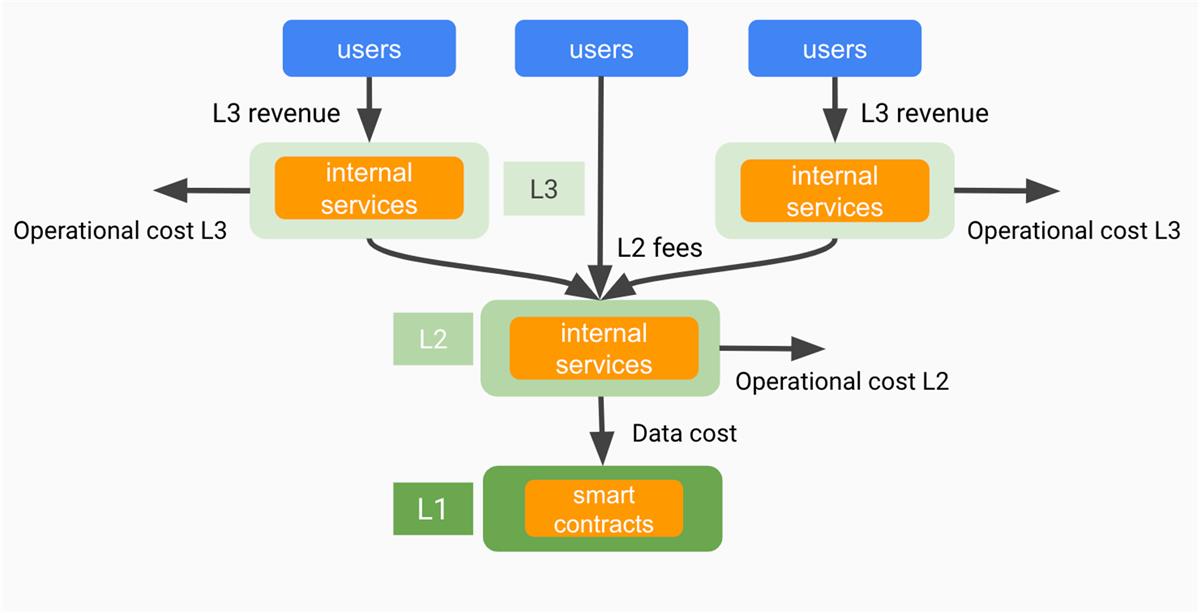

More Layers

Another active area of development involves application-specific or customized execution environments that ultimately settle on the base layer—even if indirectly. These typically target applications requiring low execution costs and simple deployment, willing to trade off some security. Examples include gaming, social media, and NFT products that don’t need to launch their own service economy or attract/safeguard large liquidity.

These include various types such as L3s, Validium, and Rollup-as-a-Service (RaaS) platforms. For example, Arbitrum Orbit is a platform supporting deployment of L3 chains atop Arbitrum L2 (One or Nova), with configurability options such as choosing between Arbitrum’s permissioned Data Availability Committee (DAC) or Ethereum L1 as the data availability layer. StarkNet and other zk rollup projects have also experimented with L3 implementations. On the extreme end of deployment simplicity are AltLayer or Caldera, offering no-code solutions for deploying “customizable” rollups, empowering users to make their own security-efficiency trade-offs.

We focus on L3 systems—essentially an additional layer built atop L2. From the perspective of an L2 rollup, this represents another source of L2 fee revenue. For the rollup ecosystem, an L3 is a new entity with its own budget balance constraints:

-

L3 revenue may come from fees, subscriptions (e.g., games), or other mechanisms like revenue sharing (e.g., NFTs).

-

L3 costs include system operating expenses and L2 fees for computation/data. These can be borne directly by the L3 or, in hosted service scenarios, paid by the RaaS platform. This adds another service provider requiring budget balance.

This is another example of economic specialization within the rollup ecosystem.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News