Creator Economy in Web3 Gaming: From Games to Platforms, Challenges of User-Generated Content

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Creator Economy in Web3 Gaming: From Games to Platforms, Challenges of User-Generated Content

Gaming is one of the few consumer-facing use cases with a real chance to scale to a billion users within the digital assets ecosystem.

Written by: Joel John, Siddharth

Translated by: TechFlow

Today we’re talking about games. For several reasons, gaming is one of the rare consumer-facing use cases with genuine potential to scale digital asset ecosystems to a billion users.

-

First, gamers are already accustomed to digital assets; they regularly pay for in-game transactions (i.e., items).

-

Second, it's a high-frequency transaction use case that our current financial infrastructure struggles to serve globally.

-

Finally, games help us distract ourselves and provide critical functions like community.

Expensive JPEGs and Nonexistent Users

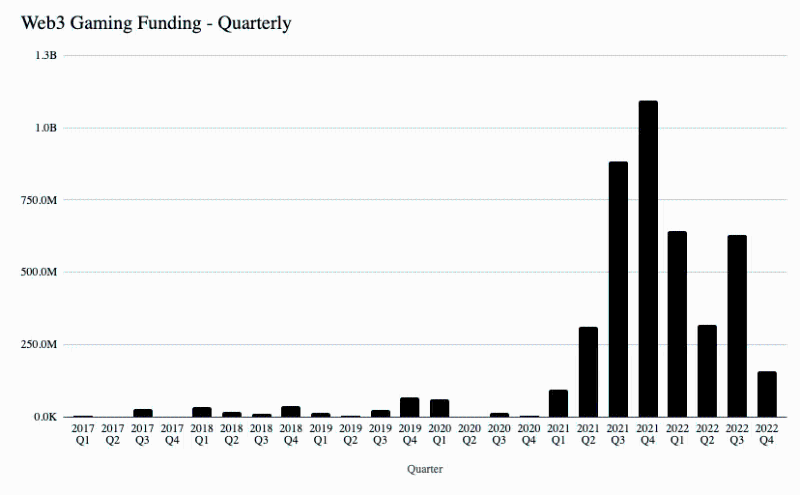

Funding for blockchain-related games surged from $83 million in 2020 to over $2.4 billion in 2021. Axie Infinity’s success drove this 30-fold spike during the dawn of a new category. The actual amount flowing into the ecosystem may be far higher, as founders and venture capital firms rush to build everything from developer tools to wallets for gaming ecosystems.

However, two years later, there’s little hype now (we know AAA titles like Fortnite take years to build).

There are several reasons:

- First, traditional gamers play games for entertainment and distraction. Currently, Web3 games focus too heavily on financial aspects, diminishing gameplay. You can't create a Web3-native version of GTA 5 or Red Dead Redemption within 18 months. And for studios with existing user bases, forcing on-chain primitives makes no sense—users loudly oppose such ideas, leading to potential chaos and poor PR.

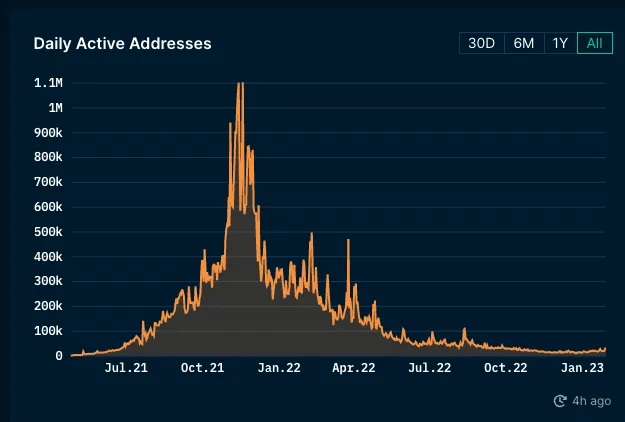

- On the other hand, bear markets hit Web3-native games like Axie Infinity, which saw a surge in new users in Q3 2021. Declining token prices mean average users care less about economic incentives tied to Web3 games. Consumers begin viewing these products as more transactional and less fun. These games cannot sustain themselves either as livelihoods or great time-passes. Daily active users and revenue quickly decline.

Established game studios with decades of experience haven’t fared much better with their Web3 projects. Ubisoft earned only $400 by integrating NFTs into one of its flagship games, Ghost Recon. The backlash was so severe that they halted all NFT-related updates within five months.

The reason is simple. When we impose Web3 as a narrative layer onto games, we add unnecessary complexity to an already functional product. Users only care if it provides exponential advantages. Over the years, players have seen studios develop increasingly aggressive methods to extract money from them.

In its current form, NFTs are just another way for studios to exploit user assets. There was a time when gamers could exchange physical copies of their favorite games with friends. That disappeared when game distribution went digital, and platforms like Steam and Origin became centralized marketplaces.

Game developers realized they could sell expansions of the original game via downloadable content (DLC) instead of full sequels. As studios sought more profit, microtransactions were introduced. In the past decade, the most controversial monetization practice in games has arguably been loot boxes—effectively lotteries sold to minors hoping for random character upgrades.

Over the past 15 years, game monetization has seen both successes and controversies. Previously, you could buy a game and fully own it without microtransactions or expansion packs. But game publishers’ economics weren’t ideal, especially for multiplayer games. Ongoing costs include server maintenance, user management, feature releases, and mechanisms to keep the game relevant.

If bundled together, these costs would make the game unaffordable for most users and ultimately lead to its demise. This is partly why modern games like Fortnite transitioned to subscription models. Additionally, ecosystems like Microsoft’s Xbox and Sony’s PlayStation offer their own bundled platform subscriptions.

Imagine game platforms as digital towns where users gather, interact, play, and often transact. Unlike early 2000s games, which were linear experiences driven by storylines, these digital products are now social commodities packaged as game experiences.

Every time a new financial primitive is introduced into games, strong opposition arises because it gives developers more power than users. Imagine going to a restaurant and paying every time you take a bite. That’s what tools like microtransactions do in their current form. Especially in Web3-native games, the “entry requirement” usually involves buying a JPEG, potentially costing a month’s salary.

To achieve fair outcomes for both players maintaining these digital domains and developers, we need financial primitives that serve both sides. Gamers already see games they’ve spent the most time in as "home." Yet, few primitives allow creators and players to own or directly profit from their in-game work.

It might seem far-fetched to imagine a market where creators earn a living through game experiences. Many will remind us that most gaming enthusiasts spend time managing communities for non-monetary benefits, like relationships they build.

Today’s Web3 games focus on better financial infrastructure and asset verification. For these primitives to become relevant, we must empower users and creators through this foundation. This is where UGC comes in.

Understanding User-Generated Content (UGC)

Most traditional studios have limited production speed. This is by design, as creating high-quality content—whether writing books or making films—is extremely time-consuming. Inspiration and transforming ideas into consumable content take time. When content is finally produced, there’s additional risk it may appeal only to a small global audience.

That’s why most big movies focus on universally relatable emotions like love and family, or rags-to-riches stories. They optimize for mass affinity. Study any traditional publisher, and you’ll find their audiences often share ideological tendencies.

The internet largely disrupted this relationship. Instead of centralized publishers producing content, everyone now creates and consumes content. Since the internet drastically reduced distribution costs, offloading expensive content creation to users eager to build audiences makes sense.

Unlike traditional media, social networks reduce content creation costs to nearly zero while capturing increasing user attention.Shifting content creation costs to users while increasing time spent on platforms gives new-era social networks powerful dual leverage, making them highly profitable.

Compared to traditional media, they gain user attention at minimal operational cost. When you scroll TikTok, Byte spends no extra resources curating your feed.Their costs are limited to content moderation and server maintenance. Facebook spent over $500 million hiring experts to manage content. Estimates suggest between 15,000 and 30,000 moderators screen content daily across social networks.

In gaming, UGC gained traction online through streaming others playing games. Gamers often enjoy watching others play, especially with entertaining commentary.

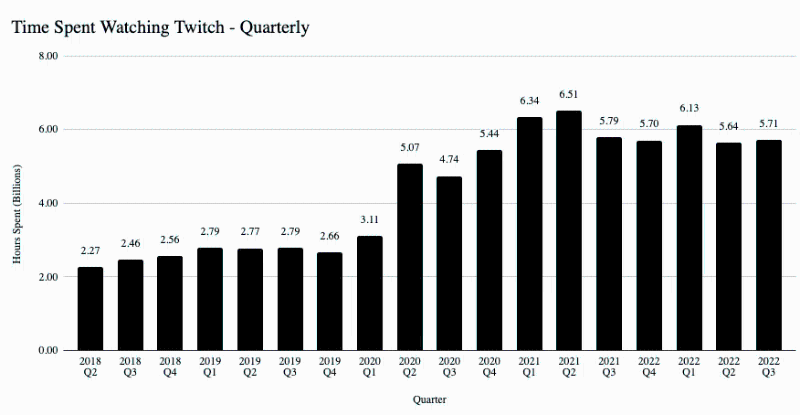

Twitch is today’s go-to streaming platform for gaming content, with viewers collectively spending 2,500 years annually watching Twitch streams.

But the fun of watching others lasts only so long. Hence, some games allow creators to build assets and sell them to others. This includes everything from simple racing games to complex strategy-based games. Suddenly, what players can do isn’t limited to what developers provide. Instead, users can infinitely vary gameplay built atop the base game.

Think of it as the difference between publishing a book and releasing a Microsoft Word document—see what unique stories your creators come up with. Game studios retain intellectual property rights over characters and code governing the world players inhabit. They also drive initial user acquisition around the game.

Games like CSGO and Age of Empires allow players to create unique levels and challenges. Fortnite has a Creative Mode enabling users to build their own worlds and characters. Far Cry 5’s Arcade Mode consists of custom game levels created by community members. Unlike mods, in-game UGC typically requires less technical expertise and is supported by built-in game mechanics. Users have discussed them since at least 2012.

From Game to Platform

UGC is a powerful lever for new games, offering two core functionalities:

-

First, it extends how long user groups can engage with the game. Linear games with progressive storylines are enjoyable until the story ends, after which players lack reasons to continue. But online modes extend a game’s lifespan and profitability. That’s why Rockstar’s GTA 5 is the most profitable entertainment product ever, generating $6 billion in global sales.

-

Second, it allows the most active contributors in the game to remain invested. Building unique levels and worlds in a digital domain fosters emotional attachment to the game. When games become channels for creative expression, feedback from other players validates their efforts. Essentially, UGC helps shift part of a game’s user base from passive participants to active creators.

Most games launch with compelling storylines (e.g., Assassin’s Creed or Call of Duty) and eventually evolve into channels where UGC becomes part of broader content offerings. Recently, games like Fortnite have developed a model where users participate less in battle royales and more in actively, chaotically, and randomly engaging with massive amounts of custom content.

The randomness brought by massive multiplayer interactions becomes a hook attracting users because gameplay becomes unpredictable. Each session offers something different. This creates an effective feedback loop, motivating users to keep using the product simply because they don’t know what to expect.

Minecraft and Roblox are exceptions to this norm—they’ve become platforms. A game that becomes a platform typically owns relatively little IP and allows fluid narratives depending on who builds on it. On these platforms, users spend more time on user-generated game experiences than on storylines or levels developed by the studio behind the game. Fortnite is in a unique transitional phase toward becoming a platform—reportedly, users now spend about half their in-game time interacting with UGC.

Over time, transitioning into a platform is the holy grail for most games, opening unique monetization avenues. For example, Fortnite partnered with over 100 brands in recent years. Moreover, its focus on becoming a UGC platform enables the game to redirect some revenue from users to creators.

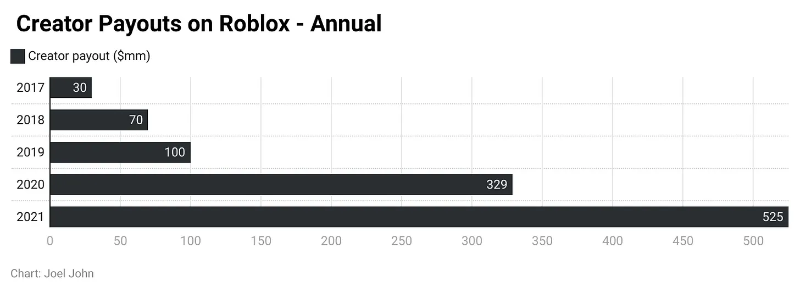

In 2021, Roblox had over 1.7 million individual users creating content on the platform. Of these, over 8,600 earned more than $1,000. Additionally, about 74 developers each netted over one million dollars. The median user accessed 40 different experiences on Roblox.

They’ve evolved from standalone media consumption goods into platforms where users create most of the user experience.

Challenges of User-Generated Content

For games aspiring to become transactional platforms, UGC is a powerful lever. But it doesn’t always work as intended. Even large game markets like Steam struggle to maintain long-term creator payouts. Back in 2015, long before NFTs or royalties emerged, Steam had a Creator Workshop section that paid over $50 million to creators making mods, skins, etc., for a few games.

At the time, only 25% of revenue was shared with creators. The program had to shut down four months later due to “unexpected user behavior.”

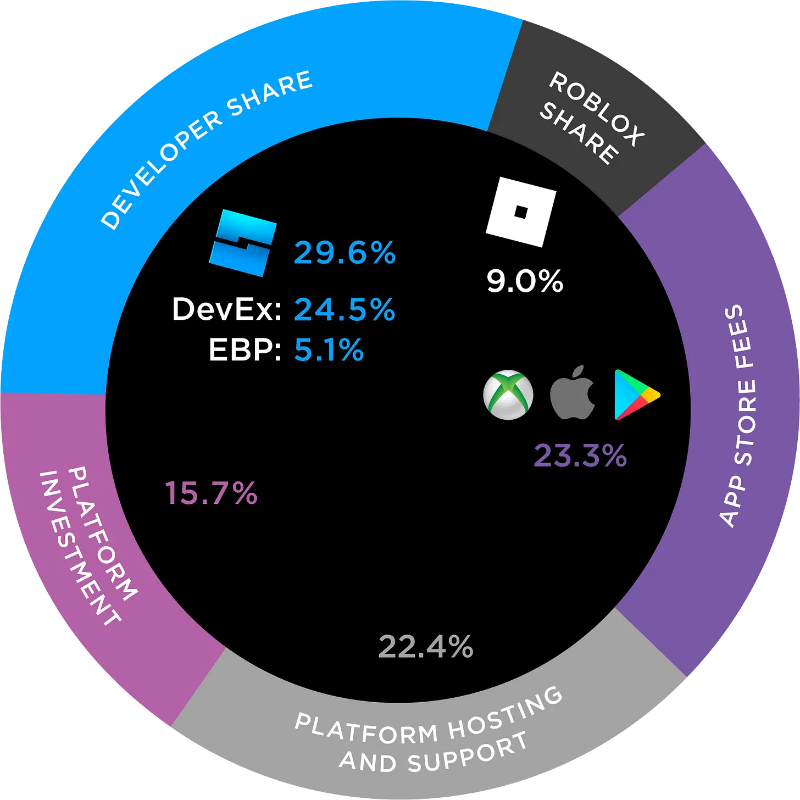

Roblox and Fortnite are powerful platforms creating entirely new forms of work. Just ten to twenty years ago, passionate gamers rarely had channels to convert their time and skills into income. Today, for every dollar spent on Roblox, developers earn an average of $0.29. If that seems low, consider that Fortnite creators earn only about 5% of the revenue they generate for the platform.

This isn’t to say game studios behind these works are stealing from creators. Maintaining the game, covering ongoing development costs, and platform fees from Xbox, Apple, or Google all incur expenses. In most cases, users are happy to receive any monetary return for their efforts.

-

From their perspective, friction stems from payment threshold requirements. For instance, due to financial transaction costs, Fortnite requires a minimum payout threshold of $100. Embedding Web3-native wallets and using tools like Stripe to pay in USDC could reduce this threshold to a fraction of its current level.

-

The other issue is today’s copyright enforcement mechanisms. It’s difficult to automatically verify and review which user first created an experience. Human intervention helps but can take weeks. Risks of copyright infringement also exist for music or art used in-game.Recently, Roblox paid $200 million in settlements for music copyright infringement. Since then, they’ve partnered with major studios to allow embedding known tracks in experiences without infringement.

You might wonder why we care so much about copyright and payments in obscure games. It’s because these virtual worlds are future workplaces for creators. In 2021 alone, Roblox paid over $500 million to creators on its platform. Distant from OnlyFans, which paid $1.6 billion to creators that year. But this shows developing, nurturing, and maintaining game experiences could become a future employment form.

If so, payment systems and copyright management must be handled via better tools requiring no human intervention. Ironically, many primitives we discuss today in blockchain ecosystems are well-suited here.

Hyper-Financialization of Games

A few weeks ago, I asked Siddharth Menon, founder of Tegro, what the most "interesting" game in Web3 is. He replied that users come to Web3 games not just for fun—their communities derive half their entertainment from financial activities.

"For me, the fun of game mechanics is a solved problem. It’s not new and has evolved over many years. However, Web3 gaming poses a new question. Games with balanced financial incentives, open economic layers, and gameplay resolving both will win. Games need to be designed not just for players, but also for investors and traders.—Siddharth Menon

This is why Web3 games appear controversial to traditional gamers. The industry is built for speculators, not today’s gamers.

Guiding users, collecting their banking information, conducting necessary anti-money laundering/KYC checks, and processing payments are your responsibilities. If done via stablecoins on-chain, this responsibility shifts to external parties (like exchanges), each under strict regulation.

This is particularly important in UGC, as suddenly you've opened doors to two things:

-

As a platform, you can reward early-stage contributors with in-game assets.

-

You can also open a marketplace allowing users to monetize hard-earned in-game assets.

These economies don’t require studios to burn cash incentivizing creators. Amy Wu elegantly explained this phenomenon in a recent talk.

In sustaining a great game, repetitiveness of content is one of the biggest challenges. UGCs, combined with token incentives and liquid markets, are powerful levers to attract creators who otherwise wouldn’t engage with Web3 gaming at all. Progress in generative content and creator incentives including tokens is still early but promising.—Amy Wu

Ideally, users who spend time playing or creating game experiences will trade acquired assets with users who lack time to play. I’m skeptical, so we reached out to Roby John from Super Gaming (one of India’s largest game studios) for validation.

Player-to-player trading isn’t new—users mining gold and trading entire accounts has existed for over 20 years. I noticed this when helping clan leaders in my games transfer top-tier items owned by elite clan members to lower-level players within their clans.

I didn’t understand this for years, but realized its importance around 2017 and built it as a feature into MaskGun itself. Today, blockchain-enabled ownership makes this easier without customer support or tool intervention.

Of course, this also removes the excitement I once felt as customer support facilitating trades of virtual AK-47s and SCAR-Hs between tribes in Tribal Wars.

In reality, two levers are at work here:

-

First, profit motives will motivate the vast majority of users to create experiences or grind within the game. Studios miss out on direct revenue by doing so. Traditionally, developers earn revenue when users buy assets directly from them. But this is balanced by reduced CAC and increased retention.

-

Second, due to player-to-player transactions, studios could earn significantly more via royalties than originally. For example, Yuga Labs and Nike each earned over $100 million in royalties from digital asset trading among their user bases.

Games like Axie Infinity represent pioneers willing to experiment with alternative models. For large studios like Epic and Ubisoft, risking alienation of existing users with different models is too great—this creates a window of opportunity for new entrants to disrupt incumbents.

Royalties aren’t some recent “breakthrough” feature discovered by games—today’s tech stack easily allows more developers to skim fees whenever users trade in-app assets. But the uniqueness lies in how closely these on-chain primitives integrate with complex financial primitive ecosystems.

Let me explain what I mean by “closeness” here. Most new Web3 games and NFT launches find their early adopters among crypto-natives. These users are accustomed to parking billions in DeFi and spending similarly on NFTs.

Li Jin, pioneer of the creator economy from Variant Fund, put it best when discussing this topic:

Using Web3 primitives in games gives creators confidence in owning the fruits of their labor. It also accelerates their means and speed of wealth creation. In the future, creators will use game assets with DeFi primitives to accelerate growth: tokenizing revenue streams, borrowing against custom art, even raising investments.—Li Jin

Many don’t adopt new Web3 primitives purely for fun. If profit-driven, they’ll bridge assets across chains, join strange secret rituals, and invest in what you’re building. Alongside their capital comes expertise in leveraging permissionless assets to boost profits.

We’ve observed users taking loans against in-game NFTs, issuing derivatives to speculate on prices, and forming DAOs to bulk-purchase in-game assets at discounts. Traditionally, these are things game developers couldn’t expect from players.

They might not want in-game asset prices collapsing due to liquidations on NFT lending platforms. But this is the benefit and risk of building permissionless, composable tools on blockchains. You never know how good—or bad—things might get.

We contacted Gabby Dizon, co-founder of YGG—one of the world’s largest gaming guilds—to evaluate these ideas:

Building user-generated content atop permissionless assets is a significant improvement over existing UGC models. It not only allows player communities to create new content but compounds network effects in ways original game developers never imagined. It also enables fairer value transfer and ownership for UGC creators.

Essentially, you're trading the certainty of user behavior within constrained environments for the randomness of users shaping your product. Sounds like an interesting version of a DAO.

Guiding the Development of UGC Economies

Web3-native games transitioning toward UGC platforms typically follow similar paths:

-

All games start by launching a core product compelling enough to attract at least thousands of daily users.

-

Once sufficient users are playing, the next step is introducing scarce assets obtainable only through prolonged gameplay. These assets usually give holders slight advantages in scoring points or winning matches.

-

Traders and players unwilling to spend days grinding acquire these assets at free-market prices.

-

At this point, games are incentivized to launch in-game marketplaces to prevent scammers and provide users with secure trading environments.

-

Assuming sufficient market liquidity and naturally occurring transaction frequency, developers may introduce native assets like Robux or Fortnite’s V-bucks. Economic models behind these currencies vary by game, but they can in turn incentivize users to generate content within the game.

But why bother with all this? Why "reward" users with on-chain tools they can trade or loan?

When asset ownership passes to users, a product unlocks two dimensions:

-

First, rather than restricting what users can do, developers let users imagine new uses. Ranging from creating lending markets for assets to building small in-game DAOs.

-

Second, it helps determine fair value for in-game assets before launching any UGC initiative. Because if you do so before establishing an active market, the platform risks being flooded with low-quality experiences designed solely to farm airdrops. This is a challenge most DeFi and NFT-native products currently face. Founders often don’t know their true user base size because they assume most users engage primarily to capture airdrops.

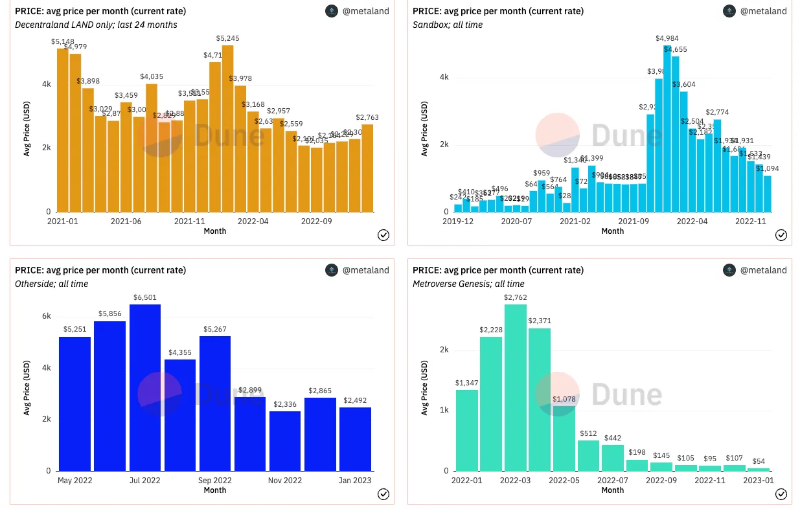

Sandbox and Decentraland were pioneers of UGC in crypto. They incentivized creators with native tokens and provided infrastructure bringing traders and creators together. But they overlooked one fact—unless you have a large enough user base genuinely interested in enjoying the product, the ecosystem won’t last. Traders typically buy land or develop experiences anticipating future profits.

But like ghost cities in China, unless real people actually want to spend time in these virtual worlds, asset prices will collapse rapidly.

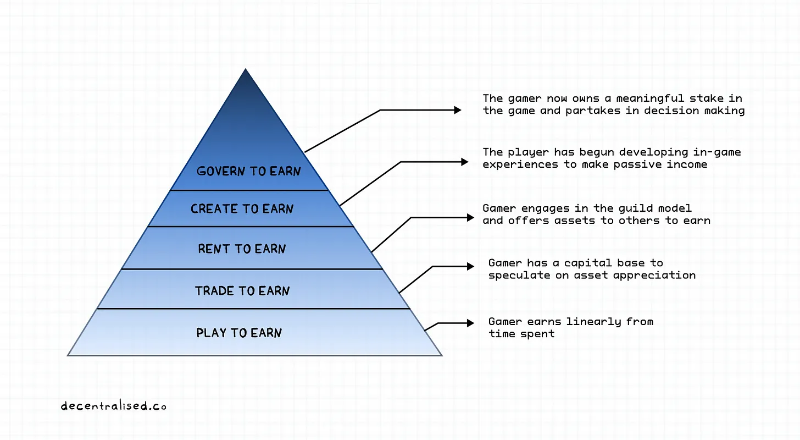

Strong UGC is likely built by focusing on gamer motivations. If Web3-native games overly emphasize economic compensation, they lose fun. Most users in P2E economies come for the extra income it generates. Such users may undergo an evolutionary arc. After spending enough time, users earn enough to buy in-game assets and trade them.

With sufficient profits, players can rent assets to others, similar to guild models. At their peak (in terms of commercial value)—players will possess enough skill to craft unique game experiences, build communities around them, and earn passive income.

This evolution of gamers—from linear income correlation to time spent, to actively creating and managing in-game experiences—is what most Web3-native studios miss today.

We often think primitives in DeFi, DAOs, and NFTs hold no value for ordinary people. The way to make them meaningful is embedding them in games and gathering sufficiently large user bases around them.

For example, if an in-game creator demonstrates sufficient commitment, they might raise funds from peers by forming a DAO. In return, contributors receive a share of revenue generated through the experience. Just as we see developers acquire and develop properties in traditional realms, we may witness studios specializing in building experiences within Web3-native virtual worlds like Sandbox.

This might seem far-fetched today, but consider that in 2021, over 70 developers earned over a million dollars on Roblox. Seven developers earned over ten million dollars.

As ecosystems around Web3-native UGC grow, we’ll witness on-chain footprints of the most active wallets. This will benefit games trying to scale by offering discounted attributes and similar incentives to creators building strong experiences across different games.

The Creativity Gap

Most Web3 games today are highly transactional economies. For this trend to reach ordinary people, we need to transition into channels for creative expression. Most social networks of today’s era achieved this shift nearly a decade ago. Creative output made platforms interesting places.

When creators move from building audiences to earning substantial money, they’ll care less about capital and more about influence. For them, creative expression will become the top priority. This might seem far-fetched, but consider that last year, one user earned $5 million from Fortnite’s Creator Support Program. Equally mind-boggling, he generated over $100 million in revenue from the game.

Consider how Gen Z and millennials generate returns from traditional assets like real estate. For the space age, we arrived too early. Our rights to "ownership" and accompanying dignity often reside in digital tools. Comparing a New York apartment to real estate in Decentraland is unfair. But early adopters of these digital domains will reap comparable or greater rewards in the next decade.

And unlike past tech booms, the internet will (ideally) grant everyone equal access to these opportunities. We heard similar arguments about ICOs and NFT mints, many of which ultimately became scams. The difference is, in games, you can’t profit merely by arriving early—creators must build things users want, otherwise digital ghost towns result.

The challenge facing most games exploring this theme is balancing community and profit motives. As we repeatedly see in protocols and DeFi primitives, profit motives of “asset owners” may lead to poor product decisions—alienating users for extended periods. This is partly why introducing UGC components into games will be gradual. Without a sticky community, you cannot bootstrap a sustainable market.

Much remains to be done. Regulators will need to recognize games as work channels, not mere entertainment. Who knows—we might see unions for in-game creators in the future. Investors may begin evaluating experience development in games through the same lens as SaaS products. Above all, creators will face a learning curve in understanding what they can do with this newly found "ownership."

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News