After the first global DAO case, how long can the "decentralized facade" of on-chain lending last?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

After the first global DAO case, how long can the "decentralized facade" of on-chain lending last?

The next breakout point for on-chain lending is undoubtedly RWA, bringing real-world assets (such as government bonds and real estate) on-chain.

By: Man Kun

Introduction

"As long as the code is sufficiently decentralized, there's no legal entity—regulators can't touch us." This was once seen as a safe haven by many on-chain lending entrepreneurs. They aimed to build an "algorithmic bank" with no CEO and no headquarters.

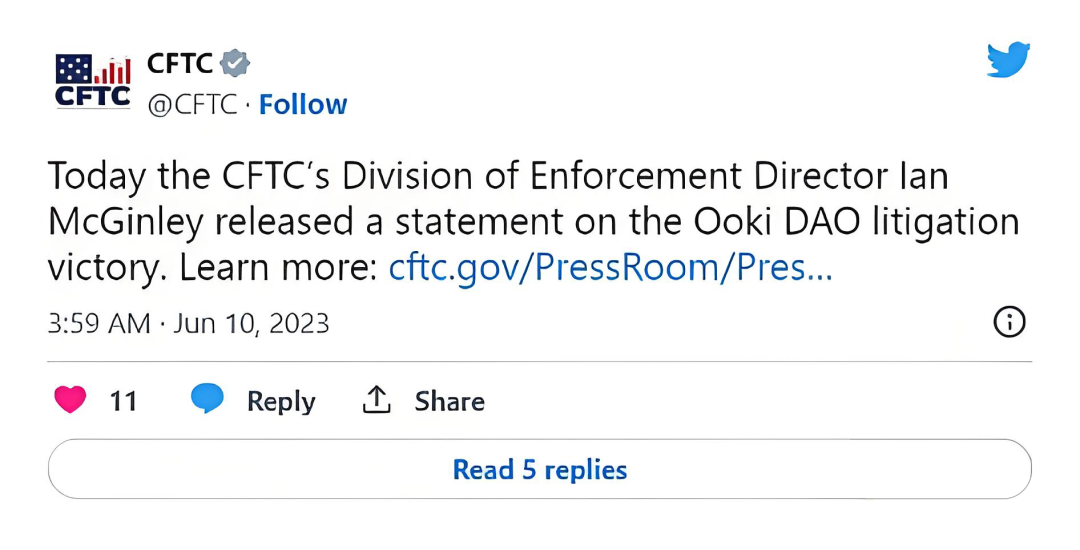

However, with the enforcement of penalties in the U.S. Ooki DAO case, this veil of "de-subjectification" is being systematically pierced by regulators. Under stricter principles of "look-through regulation," how far can on-chain lending truly go?

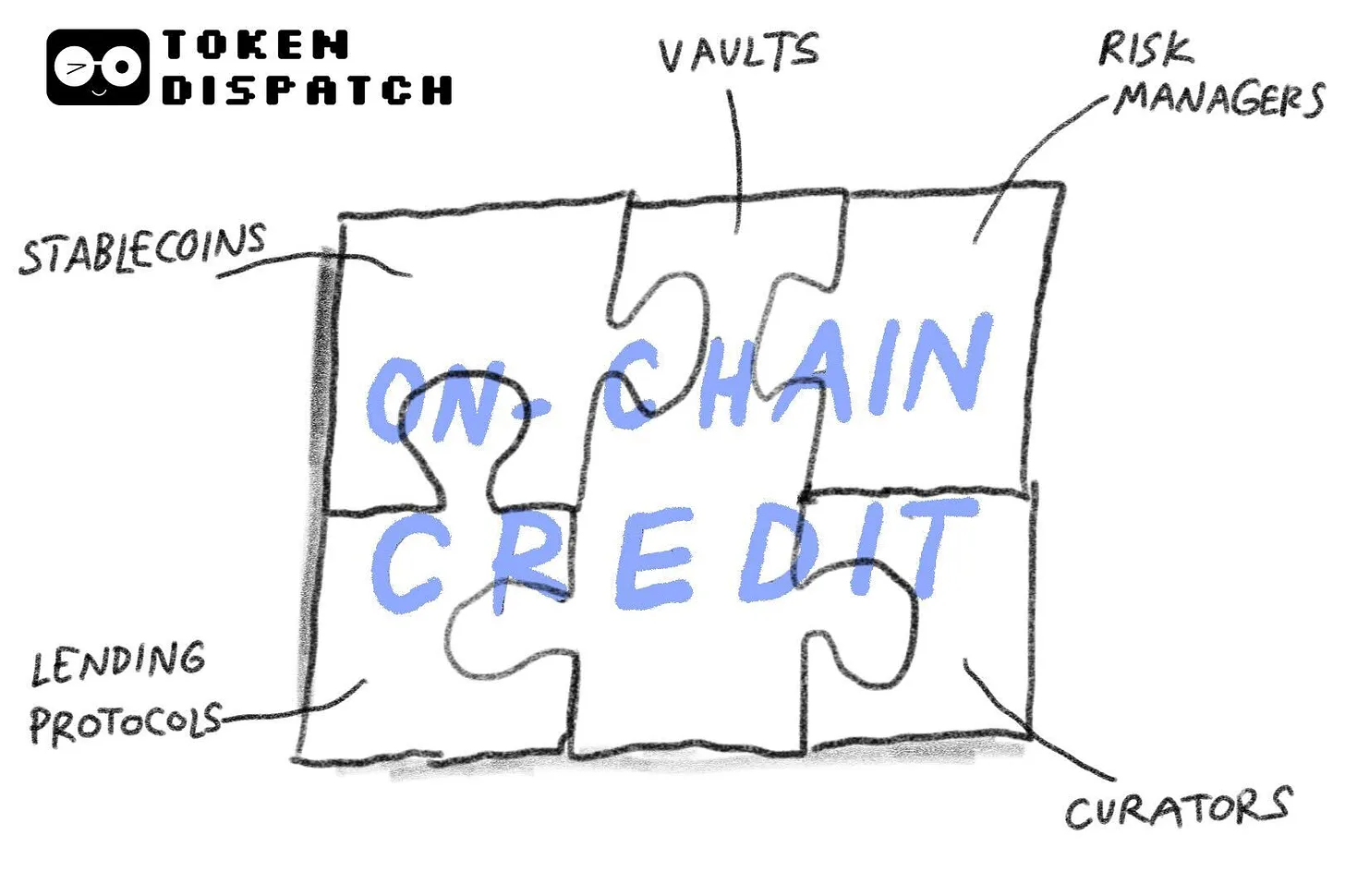

On-Chain Lending: Web3’s Autonomous Bank

Think of on-chain lending as a fully automated,无人-operated lending machine, primarily offering:

-

Automated liquidity pools: Lenders deposit funds into a publicly accessible pool managed by code, instantly earning interest.

-

Over-collateralization: Borrowers must pledge assets exceeding the loan value to mitigate risk.

-

Algorithmic interest rates: Rates automatically adjust based on supply and demand, operating in a fully market-driven manner.

This model eliminates traditional banking intermediaries, enabling a 7x24 global automated lending market. With no manual review and full execution via code, capital efficiency is greatly enhanced, asset liquidity unlocked, and native leverage provided for crypto markets.

Idealism vs. Reality: Why Do Entrepreneurs Pursue “De-Subjectification”?

In traditional finance, banks and lending platforms have clear corporate entities—someone accountable when things go wrong. On-chain lending, however, is designed to erase the "who." It seeks not mere anonymity, but a systemic architecture reflected in two key aspects:

1. Your counterparty is code, not people

You no longer sign contracts with companies or individuals, but interact directly with public, self-executing smart contracts. All lending rules—interest rates, collateral ratios—are hardcoded. Your counterparty is the program itself.

2. Decisions made by community, not management

There is no board of directors or CEO. Major upgrades or parameter changes are voted on by governance token holders distributed globally. Power is decentralized, making accountability ambiguous.

For entrepreneurs, choosing "de-subjectification" isn’t just idealistic—it’s a practical survival strategy aimed at defense:

-

Regulatory avoidance: Traditional lending requires costly financial licenses and strict compliance. By positioning themselves as "tech developers" rather than "financial institutions," teams aim to bypass these barriers.

-

Liability avoidance: In events like hacks causing user losses, teams can claim "the code is open-source and the protocol is non-custodial," attempting to avoid liability borne by traditional platforms.

-

Jurisdictional resistance: With no physical entity and servers spread globally, any single nation finds it difficult to shut down the system. This "unclosable" nature serves as ultimate protection against geopolitical risks.

The Harsh Reality: Why “Code Is Law” Doesn’t Hold Up

One: Regulatory Risks

Regulators are wary of on-chain lending due to three core underlying risks:

1. Shadow Banking:

On-chain lending essentially creates credit, yet operates entirely outside central banks and financial regulatory frameworks—an archetypal shadow banking activity. A sharp market downturn triggering cascading liquidations could pose systemic risks to the broader financial system.

2. Unregistered Securities:

When users deposit assets into liquidity pools to earn interest, U.S. SEC and similar regulators may view this as issuing unregistered "securities" to the public. Any promise of returns, regardless of technical decentralization, may violate securities laws.

3. Money Laundering Risks:

-

Liquidity pools are easily exploited by hackers: Stolen funds can be deposited as collateral, then used to borrow clean stablecoins, severing traceability and enabling easy money laundering—a direct threat to financial security.

-

Regulatory Principle: Substance Over Form

Functional Regulation: Regulators don’t care whether you’re a company or code—they care whether you're functionally performing bank-like deposit-taking and lending. If your activity is financial in nature, it falls under financial regulation.

Look-Through Enforcement: When no clear legal entity exists, regulators will target developers or core governance token holders. The Ooki DAO case set a precedent—participants in governance votes were held liable.

In short, "de-subjectification" only makes the system appear "driverless." But if it threatens financial stability or harms investors, regulators—the "traffic police"—will issue fines and find the "driver" behind the wheel.

Two: Common Misconceptions

Many entrepreneurs attempt to evade regulation through the following means, but these defenses prove fragile. Below are four common misconceptions:

Misconception 1: DAO Governance Grants Immunity – Decisions are made by community voting; you can't punish everyone.

In the Ooki DAO case, token holders who participated in voting were deemed managers and penalized. An unregistered DAO may be treated as a "general partnership," where each member bears unlimited joint liability.

Misconception 2: I Only Wrote Code – I merely developed open-source smart contracts; someone else deployed the frontend.

Despite EtherDelta being a decentralized exchange protocol, the SEC ruled that founder Zachary Coburn wrote and deployed the smart contracts and profited from them, thus bearing responsibility for operating an unregistered exchange.

Misconception 3: Anonymity Protects Me – Team identities hidden, server IPs obfuscated, untraceable.

True anonymity is nearly impossible. Converting funds via centralized exchanges, git commit logs, or social media footprints can all expose identities.

Misconception 4: Offshore Structure = No Jurisdiction – Company registered in Seychelles, servers in the cloud—SEC has no authority.

U.S. "long-arm jurisdiction" is powerful. As long as one U.S. user accesses the platform or transactions involve USD stablecoins, U.S. regulators may assert jurisdiction. BitMEX was heavily fined, and its founders jailed.

The Entrepreneur’s Dilemma: Practical Challenges of Full “De-Subjectification”

When entrepreneurs opt for complete "de-subjectification" to avoid regulation, they face significant hurdles:

1. Inability to Sign Contracts, Hindering Collaboration

Code cannot act as a legal party to sign agreements. When leasing servers, hiring auditors, or partnering with market makers, no one can legally represent the protocol. If developers sign personally, they assume liability; if not, partnerships with major institutions become impossible.

2. No Legal Recourse Against Copying

Web3 promotes open-source culture, but this allows competitors to legally fork your code, UI, and even brand with minor changes. Without a legal entity, enforcing intellectual property rights becomes extremely difficult.

3. No Bank Account, Blocking Funding and Payroll

A DAO lacks a bank account, preventing direct receipt of fiat investments or salary disbursement. This severely limits talent acquisition and blocks investment from traditional institutional players.

4. Slow Decision-Making, Missing Crisis Response Windows

Entrusting all decisions to a DAO community means every critical action requires lengthy proposal, discussion, and voting cycles. During hacks or market crashes, this "democratic process" may delay responses, leaving projects unable to compete efficiently with centralized counterparts.

Paths to Compliance: How Entrepreneurs Can “Re-Establish Subjectivity”

Facing reality, leading projects no longer pursue absolute de-subjectification, instead adopting a pragmatic "Code + Law" model—building a compliant "shell" around the protocol.

Three mainstream compliance architectures today:

1. Two-Tiered Structure Separating Development and Governance:

Operating Company: A standard software firm registered in Singapore or Hong Kong, responsible for frontend development, hiring, and marketing. It positions itself as a "technical service provider" without direct involvement in financial operations.

Foundation: A non-profit foundation established in the Cayman Islands or Switzerland, managing the token treasury and governance voting. It acts as the protocol’s legal representative, assuming ultimate responsibility.

2. DAO Limited Liability Company:

Leveraging laws in Wyoming (U.S.) or the Marshall Islands, the DAO itself is registered as a new type of limited liability company. This caps members’ liability to their contributions, avoiding unlimited personal exposure.

3. Compliant Frontend and Permissioned DeFi:

While the underlying protocol cannot block usage, the project’s official website can implement user screening:

-

Geofencing: Block access from sanctioned or high-risk regions.

-

Address Screening: Use tools to blacklist known hacker or money-laundering addresses.

-

KYC Liquidity Pools: Partner with institutions to create lending pools exclusively for verified professional users.

Conclusion: From “Code Utopia” to “Compliant Infrastructure”

The next breakthrough for on-chain lending lies undoubtedly in RWA—bringing real-world assets (e.g., government bonds, real estate) on-chain. To onboard trillions in traditional capital, clear legal entities and compliant structures are mandatory.

Compliance isn’t betraying Web3 ideals—it’s the inevitable path for mainstream adoption. The future of on-chain lending isn’t a choice between "decentralized OR compliant," but a dual-track fusion of "code autonomy + legal entity."

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News