The Coexistence Strategy of the Three Pillars of Digital Currency

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Coexistence Strategy of the Three Pillars of Digital Currency

Structural Roles of CBDC, Bank Stablecoins, and Non-bank Stablecoins and the Institutionalization Pathway in Korea

Table of Contents

CBDC VS Stablecoins

-

Digitalization of the Dual Monetary System

-

Global Trends in Hybrid Structures

-

The Necessity of CBDC

-

A New Paradigm: Parallel Structure of CBDC and Stablecoins

Bank-Issued vs Non-Bank-Issued Stablecoins

-

Objectives of Bank-Issued Stablecoins

-

Objectives of Non-Bank-Issued Stablecoins

-

Optimistic View: Functional Differentiation and Coexistence

-

Pessimistic View: Reintegration by Traditional Industries

Korea’s Approach to Stablecoin Strategy

-

Policy Environment and Fundamental Premises

-

Policy Assessment of Government Bond-Collateralized Stablecoins

-

Fostering Bank-Led Stablecoins

-

Korea’s Strategic Response

Introduction

This report analyzes the structural roles and possibilities for coexistence among central bank digital currencies (CBDC), stablecoins issued by commercial banks, and those issued by non-banks—key monetary tools in the era of digital currency—and proposes a Korea-specific institutional strategy. The traditional dual structure of the monetary system (central bank money + commercial bank money) continues into the digital age, while the emergence of non-bank entities issuing money adds a third axis, driving the evolution of the digital currency ecosystem toward a "triple-axis" model.

Given fundamental differences across issuance entities, technological infrastructure, policy acceptance, and regulatory feasibility, these digital currencies require coexistence policies based on functional differentiation and parallel structures rather than integration into a single framework. Drawing on global experimental cases, this report examines the public functions and technical limitations of various digital currencies, emphasizing particularly CBDC's role as a core instrument for international settlement and safeguarding monetary sovereignty, bank-issued stablecoins as tools for digitizing traditional finance, and non-bank stablecoins as enablers of innovation in retail economies and Web3 ecosystems.

Considering Korea’s strong emphasis on monetary sovereignty, foreign exchange management, and financial stability, this report advocates a pragmatic strategy centered on cultivating bank-led stablecoins while restricting non-bank stablecoins to limited experimentation within a regulatory sandbox. Additionally, it proposes hybrid architectures ensuring technological neutrality and interoperability between public and private infrastructures, serving as bridges connecting traditional financial systems with private-sector innovation.

By analyzing viable paths for digital currency institutionalization and strategic technology infrastructure development in Korea, this report outlines policy directions that align with global policy frameworks while ensuring the long-term sustainability of Korea’s national monetary system.

Purpose and Scope of Discussion

This report aims to analyze global issuance and circulation models of fiat-pegged digital assets and propose an institutional development roadmap suitable for Korean policymakers and industry stakeholders. Readers from other jurisdictions should interpret the content in light of their local regulatory environments.

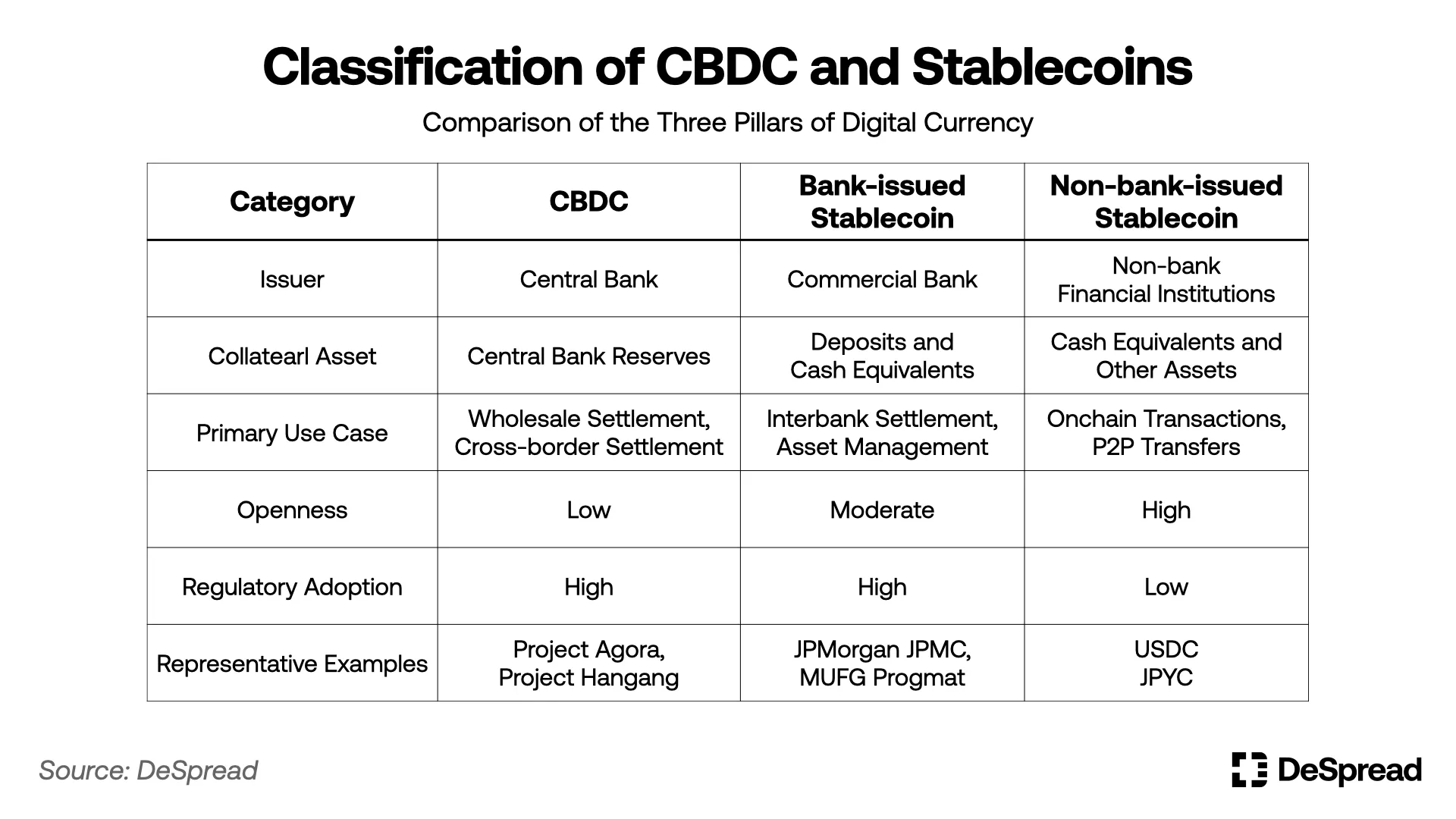

The report first clarifies two commonly conflated concepts: Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) and stablecoins. Although both claim 1:1 parity with fiat currency, they differ fundamentally in definition and use. Based on this distinction, the report further explores how CBDCs, bank-issued stablecoins, and non-bank-issued stablecoins can function complementarily and coexist institutionally within blockchain-based environments as three pillars of digital currency.

Note: The term “stablecoin” in this report refers exclusively to fully collateralized digital assets pegged 1:1 to fiat currency. Over-collateralized, algorithmic, or yield-bearing stablecoins are outside the scope of this discussion.

CBDC VS Stablecoins

1.1. Digitalization of the Dual Monetary System

The modern monetary system has long relied on a “dual structure,” comprising central bank-issued money (such as cash and reserves) and money created by commercial banks (such as deposits and loans). This architecture achieves a good balance between institutional trust and market scalability. In the digital finance era, this structure persists, represented by central bank digital currencies (CBDC) and bank-issued stablecoins. As digitization deepens, stablecoins issued by fintech firms or crypto enterprises—non-bank actors—are emerging as a third pillar, reshaping the digital currency landscape. The current digital currency ecosystem can be summarized as follows:

-

CBDC: Digital currency issued by central banks, serving as a key tool for monetary policy implementation, financial stability, and upgrading payment and settlement infrastructure.

-

Bank-Issued Stablecoins: Digital currencies issued by banks using customer deposits, government bonds, cash, or similar assets as collateral. Deposit tokens represent a 1:1 on-chain conversion of bank deposits, offering high legal certainty and close alignment with existing regulation. Alternatively, stablecoins may also be backed by off-balance-sheet assets such as cash or government bonds, including multi-bank consortium projects.

-

Non-Bank-Issued Stablecoins: Typically issued by fintech companies or crypto firms outside the traditional banking system and circulated on public blockchains. Recently, hybrid models involving partnerships with trusts, custodians, or depository banks have emerged, aiming to ensure deposit backing and institutional legitimacy.

Note: BCG (2025) categorizes digital currencies into three types based on issuer and underlying assets: CBDC, deposit tokens, and stablecoins. CBDCs, issued by central banks, serve as base money, providing public trust and final settlement capability. Deposit tokens are commercial bank deposits tokenized and placed on-chain, highly compatible with traditional financial systems. Stablecoins, issued by private entities and backed by fiat or government bonds, primarily circulate and settle within decentralized ecosystems.

However, this classification is not universally adopted by regulators. Japan, for example, emphasizes the criterion of "whether the issuer is a bank" over technical distinctions like "deposit tokens versus stablecoins." Although Japan’s 2023 amendment to the *Payment Services Act* explicitly permits stablecoin issuance, only banks, fund transfer operators, and trust companies qualify as issuers, with collateral initially restricted to bank deposits. Discussions are now underway to allow up to 50% of collateral to consist of Japanese government bonds, indicating potential coexistence between deposit tokens and stablecoins. However, restrictions on issuance rights show Japan’s framework clearly favors a bank-centric model, differing directionally from BCG’s technology-based classification.

In contrast, non-bank U.S. dollar stablecoins already dominate global markets with strong demand, making a private-sector-centered classification more realistic in the American context. For countries like South Korea and Japan, where no digital token system yet exists, a model prioritizing credibility of issuance structure and coordination with monetary policy may be more appropriate from the outset. This reflects not just technical differences but divergent policy value judgments.

Based on these considerations, this report redefines digital currencies into three categories—CBDC, bank-issued stablecoins, and non-bank-issued stablecoins—using criteria of policy acceptability, trust mechanisms in issuance structure, and alignment with monetary policy.

Table 1: Differences Between CBDC and Stablecoins

CBDC and stablecoins differ not merely in technical implementation but fundamentally in their economic roles, feasibility of monetary policy execution, financial stability implications, and governance responsibilities. Therefore, the two should be understood as complementary rather than substitutable.

Nevertheless, some countries are beginning to redesign this structural framework. For instance, China’s digital yuan (e-CNY) serves as a monetary policy tool; India’s digital rupee aims to transition toward a cashless economy; and the UK’s Project Rosalind experiments with retail CBDC accessible directly to the general public.

The Bank of Korea is similarly exploring the boundary between CBDC and digitization of private deposits. Its recent “Project Hangang” tests the interoperability between a central bank-issued wholesale CBDC designed for institutional use and commercial bank-generated “deposit tokens” derived from a 1:1 conversion of customer deposits. As part of CBDC issuance trials, this project seeks to digitize commercial bank deposits, suggesting Korea’s intent to integrate deposit digitization into the CBDC framework and avoid separate institutionalization of privately issued digital currencies.

Meanwhile, in April 2025, major Korean commercial banks (KB, Shinhan, Woori, NH, IBK, Suhyup) together with the Korea Financial Telecommunications & Clearings Institute (KFTC) began advancing plans to establish a joint venture for issuing a consortium-based Korean won stablecoin. This represents a separate track of private-sector digital currency experimentation, signaling that the distinction between deposit tokens and bank-issued stablecoins may become increasingly significant in future institutional debates.

1.2. Global Trends in Hybrid Structures

Major economies including the United States, Europe, and Japan, along with international organizations such as the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), are focusing on preserving the dual monetary structure through digital transformation. Recently, large U.S. banks such as BNY Mellon, Bank of America, and Citigroup have jointly explored wholesale stablecoin initiatives, proposing new infrastructure capable of enabling real-time interbank payments and collateral clearing without central bank involvement.

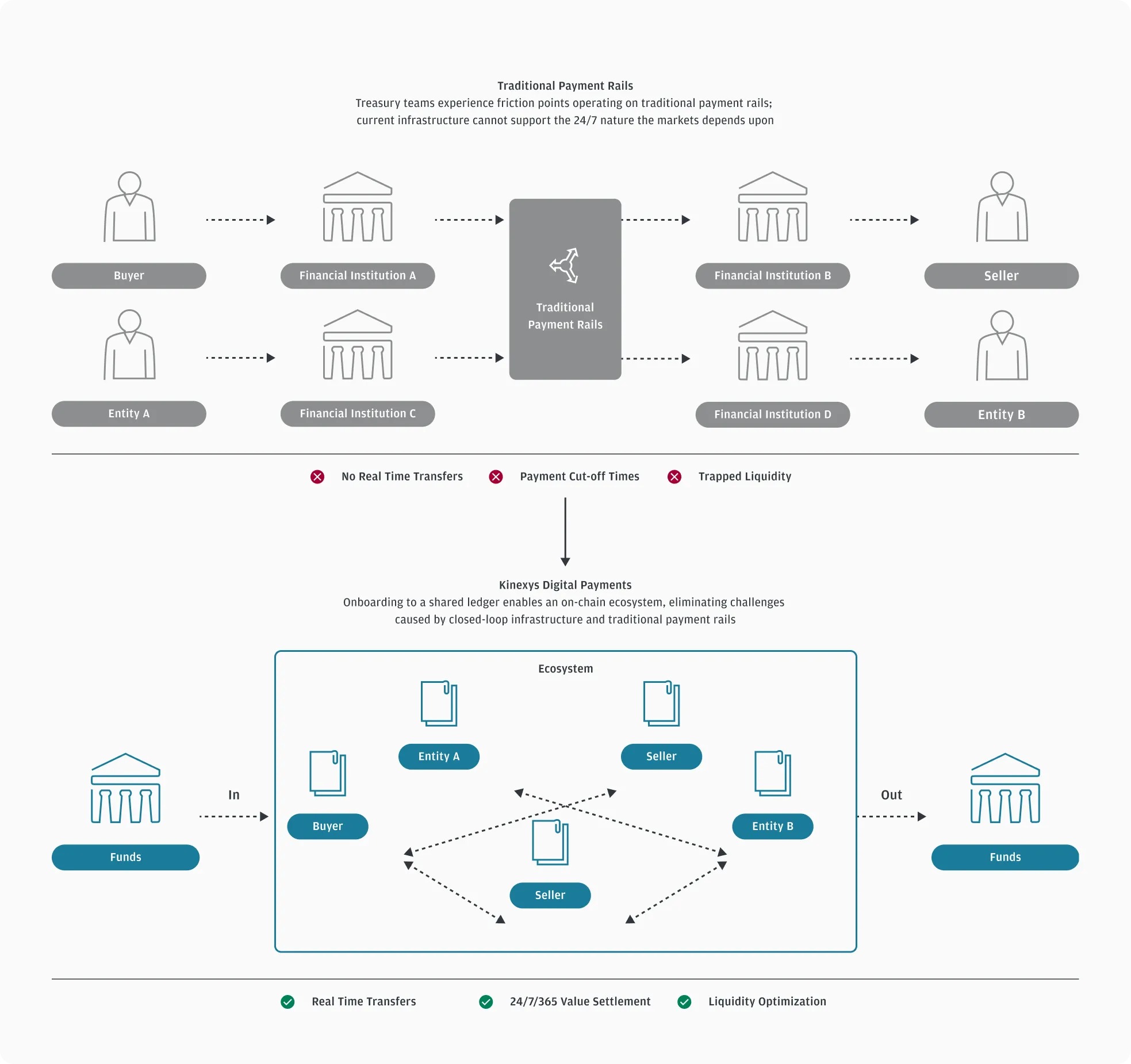

According to the BCG (2025) report, when stablecoins meet regulatory standards, privately led digital payment infrastructure can serve as an alternative in countries where CBDC rollout remains short-term unfeasible. This is evidenced by platforms like JPMorgan’s "Kinexys," Citigroup’s RLN, and Partior, which achieve high-trust digital settlements without CBDC support.

1.3. The Necessity of CBDC

As the view gains traction that bank-issued wholesale stablecoins alone can build efficient payment and clearing systems, questions arise about the necessity of CBDC in wholesale payments and inter-institutional settlements.

“Is CBDC still necessary?”

The answer is “yes.” Limitations of private-sector models extend beyond technical maturity or business reach—they face fundamental constraints in fulfilling public functions such as monetary policy transmission, legal standing, and ensuring neutrality in cross-border clearing.

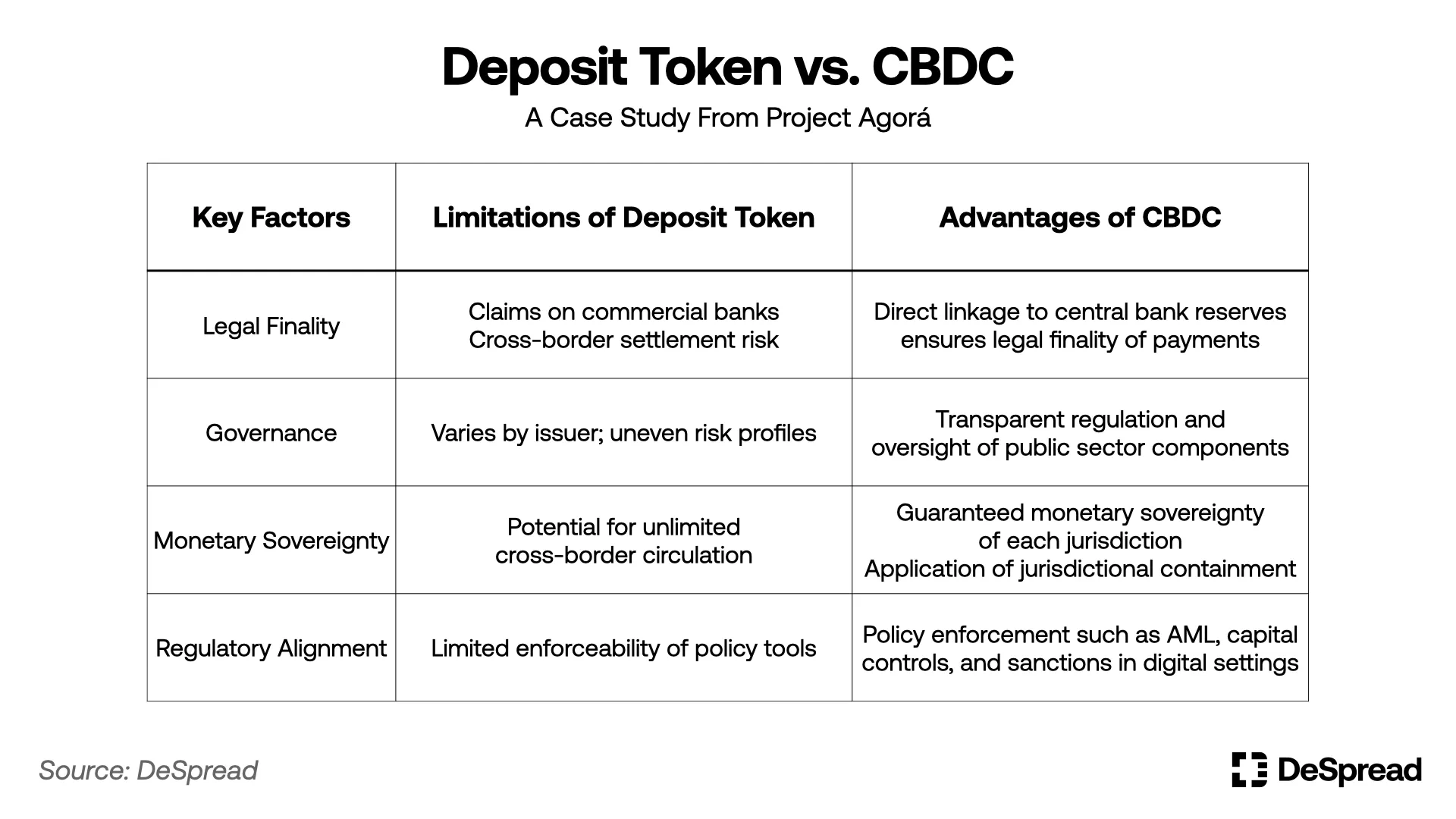

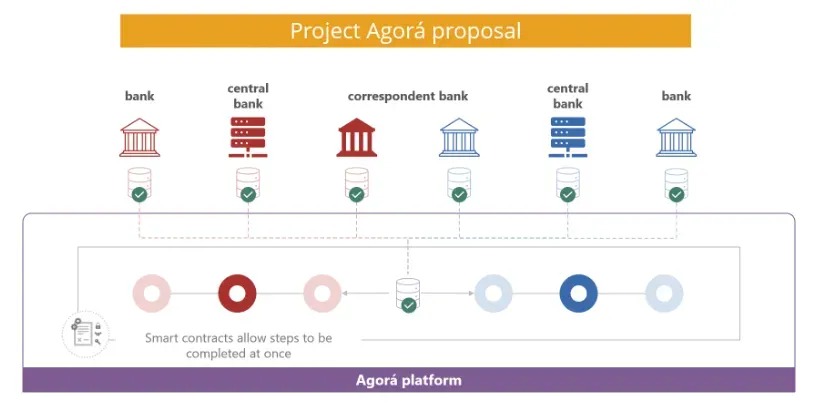

A representative case conducting systematic policy validation is Project Agorá (2024), jointly initiated by the BIS, European Central Bank (ECB), Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), IMF, seven central banks, and several global commercial banks. The project tested a parallel structure using both CBDC and deposit tokens in cross-border wholesale payment systems. It aimed to enhance interoperability between public money (CBDC) and private money (deposit tokens) while exploring design principles to preserve independence and oversight within national monetary systems. Through this experiment, BIS implicitly conveyed the following policy insights:

-

Legal Finality Gap: As liabilities of central banks, CBDCs inherently possess legal finality in settlements. Deposit tokens, however, represent claims against commercial banks and may entail legal uncertainty in cross-border transactions, leading to settlement risks.

-

Governance Asymmetry: CBDCs operate under transparent public rules and regulatory frameworks, whereas private tokens vary significantly in technical architecture and governance depending on the issuer—posing systemic risk in multi-currency, multilateral clearing networks.

-

Monetary Sovereignty and Jurisdictional Controls: To protect national monetary sovereignty, Project Agorá applied jurisdictional isolation, restricting deposit tokens to domestic financial systems and prohibiting direct cross-border circulation, thereby preventing uncontrolled spread of private money from undermining domestic monetary policy.

-

Regulatory Coordination and Policy Integration: BIS focused on embedding anti-money laundering (AML), foreign exchange controls, and capital flow regulations into digital payment networks. As public assets, CBDCs offer inherent advantages in policy integration and regulatory coordination, significantly outperforming private token solutions.

Table 2: Project Agorá’s Case for CBDC Necessity

Figure 1: Project Agorá

In essence, Project Agorá demonstrates a dual-structure design: CBDC ensures public trust and regulatory coordination in international digital payment systems, while deposit tokens provide agile interfaces for business-to-business transactions—clearly delineating their respective roles and limitations.

This architectural approach is especially critical for countries like Korea, where sensitivity to monetary sovereignty is high. The Bank of Korea participated in Project Agorá, testing digital clearing based on deposit tokens. At the “8th Blockchain Leaders Club” event on May 27, Deputy Governor Lee Jong-yeol emphasized: “Protecting monetary sovereignty from infringement is the core of Project Agorá. Korea’s deposit token design ensures it cannot be used directly in other countries,” indicating that Korea recognizes not only the technological aspects but also the importance of protecting its own monetary sovereignty within digital clearing architectures.

If Project Agorá validates the necessity of CBDC as a tool for international clearing and its coexistence with deposit tokens, then Project Pine, jointly conducted in 2025 by BIS and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), proves that central banks can digitize monetary policy operations and liquidity provision via CBDC.

Project Pine designed a mechanism where central banks automatically execute conditional liquidity provision using digital government bonds as collateral via smart contracts. Beyond mere digital transfers, the experiment demonstrated how central banks could directly adjust money supply, inject or withdraw liquidity in real time, and automate these functions on-chain.

This goes beyond indirect policy signals like benchmark interest rate adjustments, suggesting new possibilities for codifying central bank policy execution and financial system governance. In other words, CBDC is not merely a payment and settlement tool but a foundational institutional infrastructure for precise, transparent digital monetary policy.

1.4. A New Paradigm: Parallel Structure of CBDC and Stablecoins

We must regard the parallel structure of CBDC and stablecoins as a new paradigm. CBDC is not simply a “public stablecoin,” but rather the cornerstone of policy execution, clearing infrastructure, and systemic trust in the digital financial era; private stablecoins should be seen as flexible and fast financial instruments meeting end-user needs.

The key question is not “why do we need both?” We have always operated under a dual structure of central bank money and commercial bank money, and in the digital asset era, this structure will persist with changes only at the technical level. Thus, we expect the coexistence of CBDC and private stablecoins to become the new order of digital-age monetary policy.

Bank-Issued vs Non-Bank-Issued Stablecoins

As the parallel structure of CBDC and private stablecoins gradually becomes an accepted policy framework, we can refine our discussion further. Regarding the internal structure of private stablecoins, a crucial debate emerges: should bank-issued and non-bank-issued stablecoins develop in parallel, or should only one path be institutionalized?

Although both types maintain a 1:1 peg to fiat currency, they differ clearly in issuance entity, policy acceptance, technical implementation, and use cases. Bank-issued stablecoins are digital currencies issued by regulated financial institutions based on deposits or government bonds, with limited deployment on public blockchains. In contrast, non-bank-issued stablecoins primarily circulate on public blockchains and are typically issued by Web3 projects, global fintech firms, or cryptocurrency companies.

2.1. Objectives of Bank-Issued Stablecoins

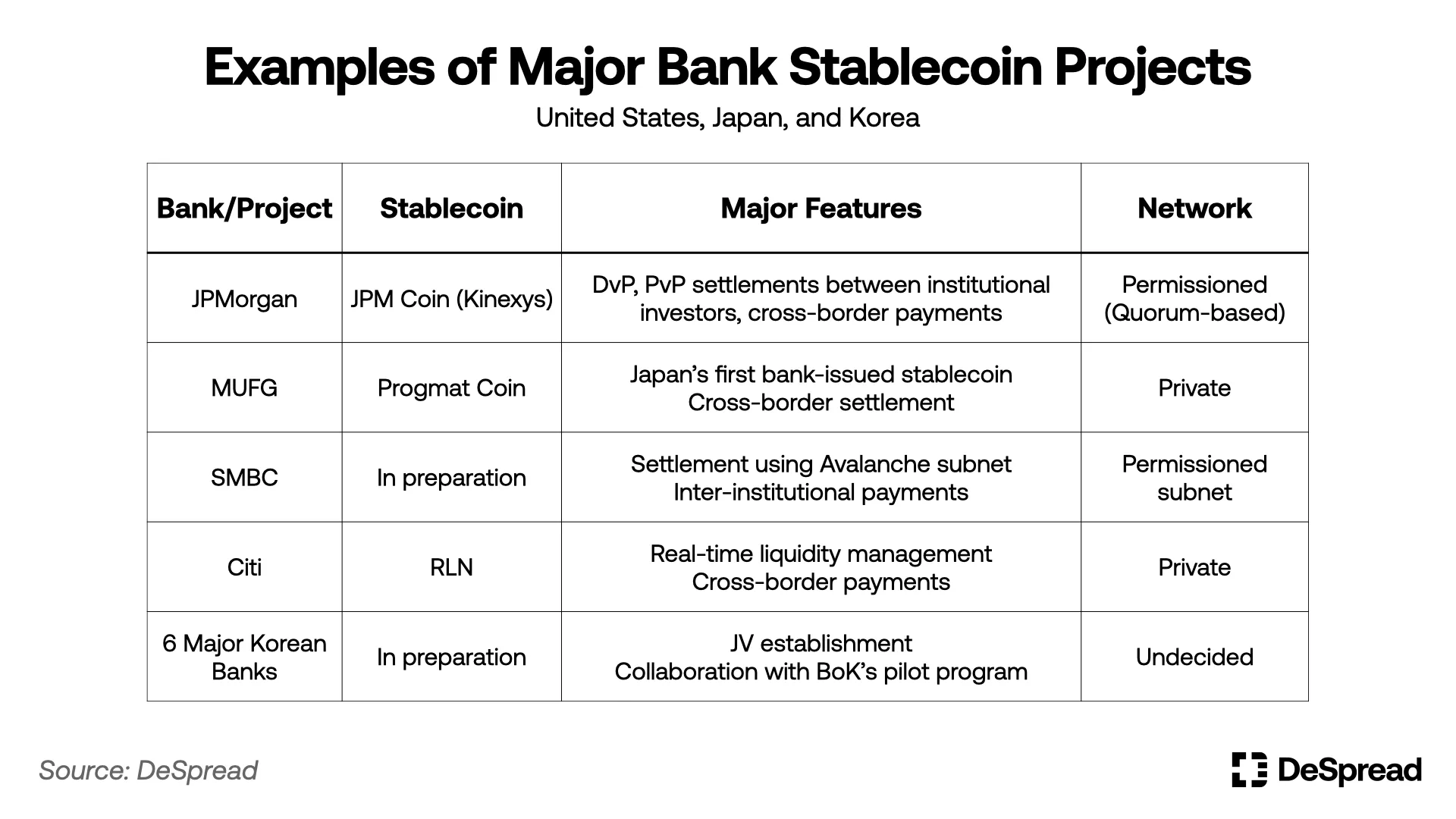

Bank-issued stablecoins digitally replicate the role of deposits within the traditional financial system. Examples include JPM Coin by JPMorgan Chase, MUFG’s Progmat Coin, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation’s yen stablecoin, and Citigroup’s RLN—all account-based stablecoins operating within regulatory frameworks covering AML, KYC, depositor protection, and financial soundness.

These stablecoins function as digital cash in institutional contexts such as delivery-versus-payment (DvP) and funds-versus-payment (FvP) settlements, trade finance clearing, and portfolio management, combining institutional stability with the flexibility of smart contract automation. They feature legal certainty, participant control based on KYC, and potential linkage to central bank reserves.

Notably, examples like JPMorgan’s Kinexys and Citigroup’s RLN operate on permissioned networks, allowing transactions only among pre-verified institutions with confirmed identities, purposes, and sources of funds—making legal liability and regulatory compliance clear-cut. These networks enable real-time payments and clearing via centralized node structures and interbank consensus protocols, freeing on-chain financial activities from the volatility and regulatory risks associated with public blockchains.

Figure 2:JPMorgan Kinexys Architecture

Commercial banks in major economies such as the U.S., Japan, and Korea are actively issuing or preparing to introduce deposit-backed stablecoins. Beyond deposit backing, there is a growing trend toward using government bonds and money market funds as collateral for bank-issued stablecoins. In the U.S., large bank alliances like Zelle and The Clearing House are discussing joint stablecoin issuance, signaling the spread of the regulated stablecoin model. Japan’s Financial Services Agency is considering raising the cap on government bond collateral in stablecoins to 50%. In Korea, six major banks (KB Kookmin, Shinhan, Woori, NH, IBK, Suhyup) and KFTC are jointly establishing a legal entity to issue a Korean won stablecoin—a move running parallel to the Bank of Korea’s wholesale CBDC experiment (Project Hangang), suggesting a future landscape of coexisting deposit tokens and stablecoins.

This trend indicates that deposit tokenization is no longer just a technical trial but a substantive step toward automating institutional payment and clearing systems. Moreover, major countries are expanding acceptable collateral types for bank-issued stablecoins to include cash equivalents, enhancing their role in regulated liquidity provision.

Table 3: Major Bank-Issued Stablecoin Cases

2.2. Objectives of Non-Bank-Issued Stablecoins

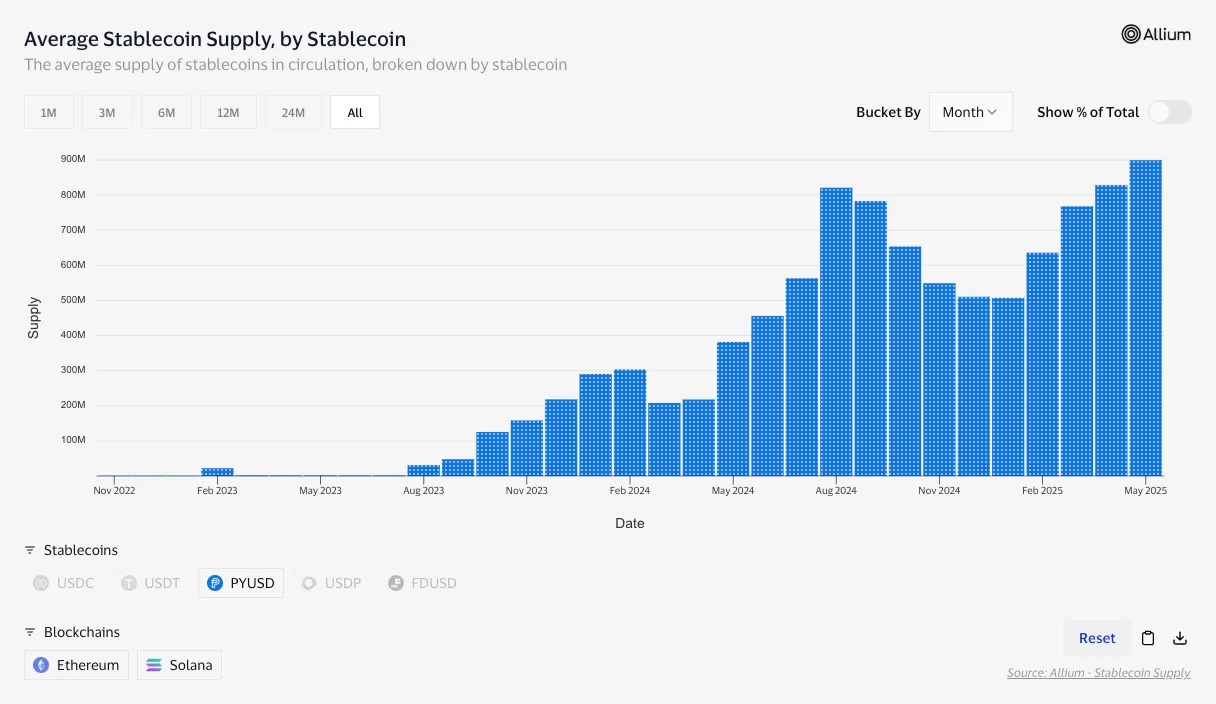

Non-bank-issued stablecoins represent a new user interface for financial innovation and global scalability. Key examples include Circle’s USDC, PayPal’s PYUSD, and StraitsX’s XSGD, widely used in e-commerce payments, DeFi, DAO rewards, gaming item trading, and P2P transfers within micro-payment and programmable finance environments. Freely tradable on public blockchains, they offer accessibility and liquidity to users beyond traditional financial infrastructure. Within Web3 and DeFi ecosystems, they have become de facto standard currencies.

The non-bank stablecoin ecosystem itself is diverse: some actors aim for disruptive innovation independent of the existing financial system, while others seek regulatory compliance and integration into institutional frameworks. For example, issuers like Circle are actively pursuing MiCA licensing and cooperation with U.S. regulators to integrate into traditional finance; others follow decentralized community-driven experimental models.

Thus, the non-bank stablecoin space embodies a zone of coexistence between innovation and institutionalization, with future policy design and market regulation significantly influencing the balance between the two.

2.3. Optimistic View: Functional Differentiation and Coexistence

The question of whether bank- and non-bank-issued stablecoins can substitute for each other should be evaluated less from a technical standpoint and more through political, policy, and industrial strategy lenses. Given their differing institutional constraints and application scenarios, the prospect of coexistence under functional differentiation is gaining recognition among policymakers and markets.

-

Bank-issued stablecoins, benefiting from legal certainty and regulatory compliance, primarily serve inter-institutional settlements, asset management, and wholesale payments. JPMorgan’s Kinexys has been operational for over four years, while Citi’s RLN and MUFG’s Progmat Coin are undergoing practical validation.

-

Non-bank-issued stablecoins are better suited for micropayments, global retail services, on-chain incentive systems, and decentralized applications (dApps), having become de facto universal currency standards within public blockchain ecosystems.

Non-bank stablecoins are vital drivers of financial inclusion and innovation. Compared to the identity verification, residency requirements, credit history checks, and minimum deposit thresholds required for bank-issued stablecoins, public blockchain stablecoins require only a digital wallet, making them highly attractive to the unbanked. Hence, they provide the only scalable access point outside the traditional financial system and serve as crucial bridges toward inclusive finance and technological democratization.

The reason bank-issued stablecoins are not deployed on public blockchains reflects regulators’ institutional resistance to such arrangements. For authorities, irretraceability, anonymity, and lack of control over on- and off-ramps constitute core compliance risks. Ultimately, any digital currency accepted by the institutional system must offer a certain degree of programmable control and export regulation. The logic of censorship resistance inherent in maximalist public blockchain ideologies inevitably conflicts with real-world financial regulatory orders.

Despite this, the non-bank stablecoin market comprises both technologically driven innovators seeking disruption and enterprises pursuing stability through regulatory compliance, showing that gradual institutionalization and experimental evolution in fintech are progressing in parallel.

The recent procedural vote in the U.S. Senate on the GENIUS Act represents an effort to formalize this trend. The bill conditionally allows non-bank stablecoin issuance, leaving room within an institutional framework for innovative market entry. Circle is attempting a shift toward regulatory friendliness through MiCA licensing and SEC oversight; JPYC in Japan is collaborating with MUFG to upgrade from a prepaid instrument to an electronic payment method. These developments suggest that non-financial actors may gradually enter institutional channels.

Non-bank stablecoins leveraging smart contracts to program AML, KYC, geographic restrictions, and transaction conditions hold promise for reconciling public blockchain openness with institutional requirements. Yet, the technical complexity of smart contracts and regulator concerns about public chains remain unresolved challenges. In this context, public blockchain stablecoins aiming for “universal access with compliance” are attracting attention.

PayPal and Paxos’s PYUSD exemplifies this goal. Circulating on public blockchains like Ethereum and Solana, PYUSD maintains 1:1 USD reserve backing via Paxos and achieves regulatory compliance through PayPal’s KYC and transaction monitoring—successfully balancing openness with oversight. Since 2024, PYUSD has expanded its influence in DeFi and retail economies, demonstrating the potential of regulation-friendly stablecoins.

Figure 3:PYUSD Supply

In May 2025, during a policy forum at the Korean National Assembly, Consumer Finance Institute Director Yoon Min-suk stated, “Stablecoin innovation is realized through participation by diverse actors such as fintech and IT firms,” advocating a multi-tiered institutionalization strategy. This trend is also evident in KakaoPay’s exploration of blockchain-based payments and the Financial Services Commission’s ongoing discussions on stablecoin regulation.

In this context, the key realization is that non-bank stablecoins do not necessarily conflict with or replace the institutional system but instead fill gaps left by existing financial systems, demonstrating possibilities for coexistence. Their inclusion of the unbanked, practical utility in public blockchain-based Web3 ecosystems, and ability to enable fast, low-cost global payments are functionalities that bank-issued stablecoins alone cannot fulfill. Thus, the two achieve functional differentiation in their optimal roles—not as competitors, but as balanced, collaborative components.

2.4. Pessimistic View: Reintegration by Traditional Industries

There is also skepticism about the long-term viability of the current “functional coexistence” narrative. After all, many technologies that spark innovation in niche markets often get absorbed and consolidated by traditional industries as they mature. Indeed, traditional financial players are now taking the stablecoin market seriously and are unlikely to stand idle.

Major U.S. banks have begun preliminary discussions around joint stablecoin issuance through alliances like Zelle and The Clearing House. This is a strategic move anticipating potential losses in foreign exchange fees, retail payment commissions, and wallet dominance should legislation like the Genius Act pass, as noted in reports.

In such a scenario, even if non-bank stablecoins achieve technological superiority or widespread adoption, they may ultimately face absorption or marginalization by bank-dominated infrastructures. Banks, in particular, can use central bank reserves as collateral for stablecoins, potentially giving them competitive advantages in credibility and efficiency over traditionally collateralized stablecoins. That is, public blockchain-based stablecoins may face structural disadvantages in institutional networks and collateral capabilities.

While Visa, Stripe, and BlackRock do not issue stablecoins directly, they integrate USDC into payment networks or launch tokenized funds (e.g., BUIDL), absorbing stablecoin innovations into existing financial infrastructure and redefining them in forms compatible with institutional systems. This strategy leverages the potential of stablecoins while maintaining traditional financial stability and trust.

This trend is clearly reflected in the case of StraitsX’s XSGD. Though issued by a non-bank financial institution, XSGD is fully backed by deposits held at DBS Bank and Standard Chartered and operates on a closed-network infrastructure built on Avalanche Subnet.

Subnet: An enterprise-grade network structure allowing full customization of openness, consensus mechanisms, and privacy levels, specifically designed for regulatory compliance.

XSGD’s ability to access public chains via Avalanche’s C-chain and circulate across multiple networks is a special case enabled by Singapore’s open regulatory environment. Similar structures would likely face difficulty in more conservative jurisdictions, where both issuance and distribution channels might be confined to regulated, permissioned frameworks. While XSGD symbolizes compromise between institutional systems and technology, in more restrictive environments, the advantage of the bank-led model may become even stronger due to practical constraints.

JPMorgan’s Kinexys clearly illustrates the convergence of asset management and settlement into bank-controlled digital financial networks. BCG analysis suggests that public blockchain-based stablecoins face structural limitations in regulatory acceptance, and only models based on financial institutions can sustainably exist within institutional systems.

Although Europe’s MiCA formally opens issuance to all entities, in practice, capital requirements, collateral management obligations, and issuance caps create barriers that make entry difficult for non-financial institutions. As of May 2025, aside from Circle’s pending license, few entities have officially registered as electronic money token issuers.

In Japan, the 2023 revision of the *Payment Services Act* restricts issuance of electronic payment-type stablecoins to banks, trust companies, and fund transfer operators. Public blockchain-based tokens can only circulate on select exchanges and do not receive official payment instrument status.

The “programmable, compliance-ready stablecoin” model mentioned in the optimistic view, while seemingly increasing institutional acceptability, faces complex institutional hurdles in achieving international regulatory alignment, legal recognition of smart contracts, and assignment of risk liability. Even if technically feasible, regulators are likely to continue prioritizing issuer credibility, capital strength, and controllability as core criteria.

In the end, non-bank stablecoins acceptable to regulators may reduce to “private entities operating like banks,” diluting the decentralization, inclusivity, and censorship resistance originally promised by public blockchains. In other words, the optimistic belief in long-term functional coexistence may be overly idealistic; digital currency infrastructure may ultimately consolidate around large-scale, trusted, institutionally backed entities.

Korea’s Stablecoin Strategy

3.1. Policy Environment and Fundamental Premises

Korea is a country where policy priorities strongly emphasize monetary sovereignty, foreign exchange management, and financial regulation. Interest rate-based monetary policy, centered on the central bank, has effectively controlled private-sector liquidity, with the Bank of Korea prioritizing predictability and monetary stability through policy rates. Under this structure, the emergence of new forms of digital liquidity raises ongoing concerns about potential disruptions to monetary policy transmission and existing liquidity management frameworks.

For example, stablecoins issued by non-bank entities using government bonds as collateral, although not based on central bank-issued base money (M0), may perform monetary functions on-chain, generating endogenous money creation effects in the private sector. If these off-system digital cash equivalents are not captured by monetary aggregates (M1, M2, etc.) or distort interest rate transmission, authorities may perceive them as “shadow liquidity.”

Such policy risks have been repeatedly raised internationally. FSB (2023) warns that unregulated expansion of stablecoins could threaten financial stability, citing risks of cross-border liquidity shifts, AML/CFT evasion, and ineffective monetary policy. BIS (2024) analysis also suggests that in some emerging economies, stablecoins may lead to informal dollarization, weakening monetary effectiveness due to deposit outflows from banks.

In response, the U.S. adopts a pragmatic institutionalization strategy via the Genius Act. The bill allows private stablecoin issuance but imposes conditional licensing through stringent collateral requirements, federal registration, and eligibility restrictions—a strategic move to absorb risks into a regulated framework rather than ignore FSB and BIS warnings.

The Bank of Korea has expressed clear concerns regarding such policy risks. Governor Lee Chang-yong stated at a press conference on May 29, 2025: “Stablecoins are private substitutes for money that may undermine the effectiveness of monetary policy,” expressing concern that won-pegged stablecoins could trigger capital flight, erode trust in payment systems, and circumvent financial regulation. He emphasized, “We should start with regulated banks.”

However, the Bank of Korea has not imposed a blanket ban but instead manages and reviews pathways for institutionalization under controllable risk conditions. In practice, beyond CBDC, it supports payment experiments involving deposit-tokenized digital currencies issued by commercial banks (Project Hangang), conditionally accepting private-sector digital liquidity trials.

In summary, stablecoins may act as new variables in monetary policy. International bodies and Korean authorities are not concerned about technological possibility per se, but about under what conditions and within what frameworks this technology should be accepted into the monetary system. Therefore, Korea’s stablecoin strategy should not be unconditional openness or technology-first design, but a structured approach that sets parallel policy and technical prerequisites under the premise of institutional acceptance.

3.2. Policy Assessment of Government Bond-Collateralized Stablecoins

3.2.1 Relationship with Monetary Policy

Stablecoins collateralized by government bonds or other cash equivalents may appear to be secure-asset-backed digital currencies, but from a monetary policy perspective, they may function as private-sector money issuance structures beyond central bank control. This goes beyond being mere payment tools, potentially creating broad money (M2)-like liquidity without passing through base money (M0) channels.

The Bank of Korea typically influences broad money (M2) structure indirectly by adjusting the policy rate to guide commercial bank deposit rates and credit supply. However, cash-equivalent-collateralized stablecoins may bypass this monetary policy transmission channel, enabling non-bank entities to directly supply liquidity to the real economy via digital assets. Particularly concerning is that this process may escape traditional monetary controls such as capital regulation, liquidity ratios, and reserve requirements—posing a structural threat from the central bank’s viewpoint.

More importantly, government bonds are originally instruments for settling previously issued liquidity through fiscal policy. Using them again as collateral to issue another layer of liquidity (stablecoins) effectively creates a secondary monetization process by non-central banks—an outcome akin to a “double monetization structure.” Consequently, systemic liquidity may expand independently of the central bank’s interest rate signals, weakening the transmission power of policy rates.

BIS (2025) analysis confirms that inflows into stablecoins reduced yields on U.S. short-term Treasuries (3-month T-bills) by 2–2.5 basis points within ten days, while outflows increased yields by 6–8 basis points—showing asymmetric effects. This indicates that stablecoin flows alone can set interest rates in short-term funding markets ahead of central bank policy, potentially undermining the forward-looking influence of benchmark rates.

This structure may also affect real interest rates. If stablecoin-generated liquidity begins to materially impact asset prices and short-term rates within the financial system, the effectiveness of benchmark rate adjustments could diminish, turning the central bank from a “leading rate-setter” into a “market follower.”

Yet, it is difficult to conclude that all government bond-collateralized structures immediately invalidate monetary policy or pose severe threats. In fact, the U.S. Treasury April 2025 report interprets such stablecoins as “digital conversion of existing monetary assets,” arguing they do not alter total money supply. The actual impact of bond-collateralized stablecoins varies with operational design and policy environment, requiring nuanced evaluation rather than blanket judgment.

Therefore, government bond-collateralized stablecoins exhibit a dual nature—carrying both risks and practical benefits. Their policy acceptance hinges on how their structure integrates with the existing monetary system and whether they can be designed without compromising the predictability and credibility of policy tools.

3.2.2. Global Comparison

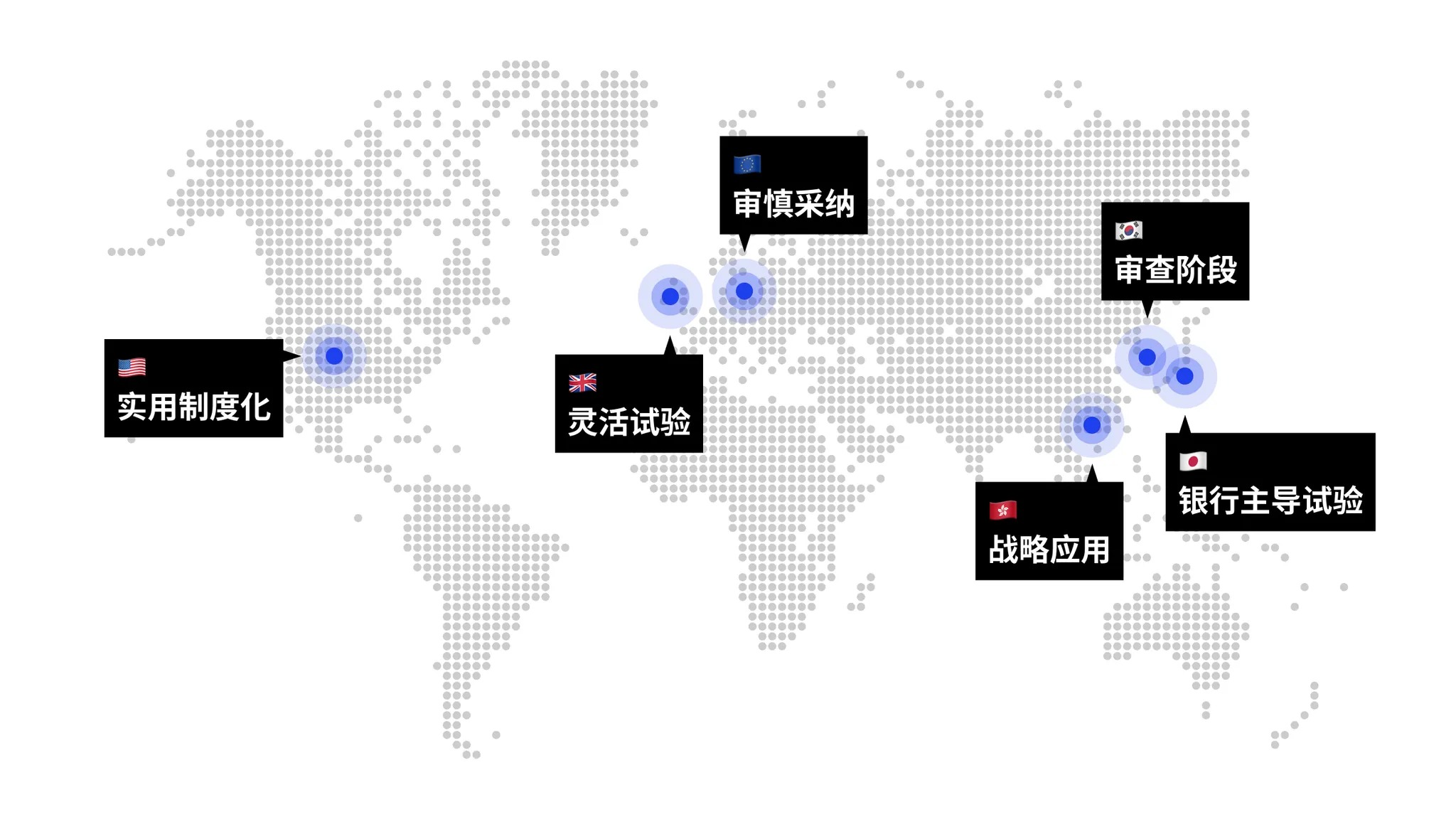

National policies on cash-equivalent-collateralized stablecoins vary based on differences in monetary system design, capital market depth, complexity of interest rate transmission, and regulatory philosophy toward digital assets. Notably, the U.S., Europe, Japan, and Korea differ in their approaches to managing tensions between stablecoin institutionalization and monetary policy.

Figure 4: Comparative Stablecoin Policies Across Major Economies

-

United States: With deep capital markets and a multi-layered interest rate transmission mechanism involving the Federal Reserve, money market funds, and deposit institutions, it is generally believed that bond-collateralized stablecoins will not immediately threaten monetary policy. Products like Circle’s USDC, BlackRock’s sBUIDL, and Ondo’s bond-fund tokens demonstrate liquidity structures linking digital assets with money market funds, viewed as instruments of securitization and financial innovation. The proposed Genius Act represents legislative momentum to formalize private stablecoins under conditions such as high-credit collateral and issuer registration.

-

Europe: The European Central Bank (ECB) maintains a more conservative and restrictive stance toward private stablecoins. MiCA imposes strict requirements on capital adequacy, redemption rights, and collateral transparency, effectively implying that only financial institutions can become issuers. The ECB fears private stablecoins could compete with the digital euro or circumvent monetary policy, thus prioritizing institutional stability over technological experimentation.

-

Japan: Given its ultra-low interest rate environment and bank-centric credit creation, Japan has limited monetary policy flexibility. Hence, it views private stablecoins as auxiliary tools for digital credit expansion. Bank-led models are most actively discussed, with consideration to allow partial holding of government bonds as reserves for stablecoin issuance. Preference leans toward private, permissioned chain structures to build regulator-friendly environments.

-

South Korea: Due to its interest-rate-focused monetary policy and relatively shallow capital markets, Korea ranks among nations most concerned about the monetary policy implications of bond-collateralized stablecoins. Since 2023, the Bank of Korea has repeatedly warned in reports: “In a system where liquidity is adjusted via policy rates, inflows of digital currencies may weaken the credibility of monetary policy.” Governor Lee Chang-yong stated in May 2025: “Privately issued stablecoins may function like money; issuance by non-bank institutions should be approached cautiously.” Korea is currently advancing wholesale CBDC trials alongside deposit-token-based payment experiments by commercial banks.

-

United Kingdom: In a consultation paper released in May 2025, the UK indicated that stablecoin collateral could include not only short-term but also partial long-term government bonds. This grants issuers broader discretion in asset composition and is seen as a regulatory experiment acknowledging market flexibility and private-sector autonomy.

-

Hong Kong: Given its HKD-USD peg, Hong Kong allows USD-denominated assets like U.S. Treasuries as stablecoin collateral. This is not merely a financial experiment but linked to strategic goals of extending the HKD-USD peg into digital liquidity, reflecting central authorities’ intent to leverage stablecoins in reinforcing foreign exchange architecture.

Stablecoin policies worldwide reflect not just risk management or monetary effectiveness but also deeper macroeconomic objectives tied to capital market characteristics, foreign exchange strategies, and positioning as global financial centers. The UK and Hong Kong cases highlight the importance of such strategic thinking. This suggests Korean policymakers should not treat stablecoins solely as “objects of control” but consider how to utilize them as “strategic tools” to deepen capital markets, improve international settlement efficiency, and strengthen foreign exchange strategy—thereby fueling long-term economic growth. Such an approach requires moving beyond pure risk avoidance toward opportunity capture.

3.3. Fostering Bank-Led Stablecoins

3.3.1. Institutional Role and Importance of Deposit-Backed Stablecoins

Deposit-backed stablecoins issued by banks (deposit tokens) are regarded by policymakers as among the most credible forms of digital liquidity. This model issues tokens based on existing deposit balances, enabling digital circulation without increasing money supply or distorting interest rate policy, thus enjoying high institutional acceptance.

However, deposit-backed stablecoins are not risk-free. Liquidity risks, capital adequacy concerns, and extended usage beyond deposit insurance coverage must be considered in institutional design. Especially under large-scale on-chain circulation, impacts on bank liquidity structures or payment network operations necessitate a risk-based approach.

Despite this, policy remains relatively favorable toward deposit-backed stablecoins for the following reasons:

-

Linkage to depositor protection systems enhances consumer safeguards.

-

Manageable within existing reserve requirement systems and interest rate policy frameworks.

-

Easier compliance with AML/CFT and foreign exchange regulations under commercial bank supervision.

Some argue that non-bank stablecoins collateralized by government bonds could foster fintech ecosystem innovation. However, much of this can also be achieved via deposit-based models. For example, if global fintech firms require a Korean won stablecoin, domestic banks could issue and provide it via APIs. Such API access could include functionalities beyond simple remittance—stablecoin issuance, redemption, transaction history lookup, KYC status verification, custody confirmation—allowing fintech firms to integrate stablecoins as payment tools or build auto-clearing systems linked to user wallets.

This model operates within bank regulatory frameworks, satisfying depositor protection and AML/CFT requirements while enabling flexible user experience design for fintech innovation. When banks act as issuers, they can manage circulation volumes under risk-based frameworks and pursue both stability and scalability via on-chain payment APIs connected to internal clearing networks.

From this perspective, the deposit-based stablecoin model responds to private-sector innovation demands without affecting monetary issuance rights or monetary policy, representing a pragmatic solution balancing institutional stability and technological scalability.

Policy remains cautious toward public blockchain-based non-bank stablecoins. In a country like Korea—with highly developed financial infrastructure and a low unbanked population—the mere presence of public blockchain technology does not sufficiently justify innovation or necessity.

JPMorgan and MIT DCI (2025) note that existing stablecoins and ERC standards still suffer technical limitations insufficient for real-world banking payment needs. The report proposes new token standards and smart contract design guidelines incorporating regulator-friendly features, forming important reference points for Korea’s assessment of public blockchain payment tokens. Hence, first validating bank-issued stablecoins with proven technical and institutional fit, then gradually evaluating public blockchain expansion as global standards emerge, offers a balanced path toward policy stability and market innovation.

Moreover, we should no longer assume reliance on fully closed private chains like Corda, Hyperledger, or Quorum. Modern architectures now allow customizable blends of openness and closure, interoperability between private environments, and selective connection to public chains when needed. Flexible hybrid infrastructures are not one-way closed systems but foundations enabling coexistence between institutional systems and private innovation.

In this context, for public blockchain stablecoin policy discussions to gain traction, proponents must present concrete business proposals, circulation roadmaps, and technical implementation plans proving that such stablecoins genuinely enable liquidity creation and innovative use. Otherwise, isolated liquidity pools like Uniswap’s JPYC case may recur, reducing institutional acceptance.

Ultimately, policy persuasion lies not in “we must go on public chains,” but in demonstrating what substantive needs the structure fulfills, what industrial applications it enables, and what spillover effects it generates.

3.3.2. Priority Areas for Blockchain Implementation

If deposit-backed stablecoins issued by banks become the core pillar of institutional digital liquidity, the priority areas for their deployment in financial infrastructure become clear. This should not be mere digitization of payment methods but a technological shift aimed at solving structural challenges such as inter-institutional trust coordination, cross-border asset transfers, and ensuring interoperability between systems. For domestic inter-institutional transactions and payment infrastructures already highly advanced via centralized systems, blockchain adoption may offer limited necessity or benefit. Conversely, in cross-border asset and payment flows or complex inter-institutional structures, blockchain can be a powerful tool for efficiency.

-

Payment Network Clearing: Deposit-backed stablecoins can enhance the efficiency of international funds transfer and clearing infrastructure. Applications include improved FX settlement (e.g., Project Jura), automated trade payments via electronic letters of credit and invoices (e.g., Project Guardian smart contracts), and supplementary clearing functions for RTGS in international payment networks (e.g., Project Agorá). As seen in Contour and TradeLens, success depends not just on technology but also on unified participation and platform alignment.

-

Securities Clearing and Asset Management: Can play a pivotal role in streamlining capital market securities holding and clearing. Transitioning domestic securities settlement to T+0 and DvP models (e.g., DTCC’s Project Ion and Smart NAV), implementing on-chain asset management combining RWA and deposit tokens (e.g., JPMorgan Kinexys), maximizing liquidity and operational efficiency.

-

Other Potential Applications: High-value-added domains where blockchain structurally resolves existing system limitations, such as on-chain securitization of recurring cash flows or efficiency improvements in overseas securities settlement. These areas benefit from blockchain’s advantages in legal contract transparency, settlement certainty, speed, and efficiency.

These are areas where existing systems face clear limitations in cost, time, and risk management—precisely where blockchain offers structural solutions. Most importantly, adopting the same blockchain infrastructure used by overseas financial institutions increases the likelihood of Korea’s digital finance directly connecting to global networks.

Further, if Korea’s permissioned blockchain structures evolve into internationally interoperable technical standards, they could expand into direct connections with foreign financial institutions, FX swaps, trade settlements, and joint issuance and circulation of securities. Cross-border financial interoperability would transcend mere technical choice, becoming a strategic digital asset for the national economy.

3.3.3. Requirements for Applicable Technical Infrastructure

As the application domains for bank-issued deposit-backed stablecoins become clearer, the technical infrastructure supporting their deployment must also be specified. The core challenge is balancing the need for regulatory compatibility, transaction privacy, system control, and high-performance processing—essential for institutional finance—with the advantages of on-chain automation and global interoperability offered by blockchain.

The most promising solution is building customizable permissioned blockchain systems, each tailored to user needs and capable of native interoperability between sub-chains. This allows compliance with AML/KYC, regulatory-grade privacy protection, and high-speed clearing, while optionally enabling external chain connectivity when needed.

A prime example is the Avalanche Subnet architecture. Combining the controllability of private chains with cross-chain interoperability, its main features include:

-

Access Control and Regulatory Compliance: Network participants are limited to pre-approved institutions or partners, with all transactions executed only after KYC/AML verification.

-

Data Privacy Protection: Real user identities are not stored on-chain, using a regulator-accessible pseudonymous model.

-

Selective External Connectivity: Enables interoperability with public chains or other subnets when required.

SMBC plans to issue a yen stablecoin on an Avalanche Subnet, building a closed system accessible only to authorized partners. As this major Japanese bank begins practical use of Subnet-based stablecoin transactions, Korea’s adoption of a similar architecture could create an environment for real-time testing of wholesale stablecoin interoperability between JPY and KRW.

JPMorgan’s Kinexys issues deposit-backed stablecoins on its proprietary permissioned chain (based on Quorum), automating specific financial operations such as FX trades, repo transactions, and securities settlements. While Kinexys has long operated on Quorum, it recently began testing Avalanche Subnet’s privacy-enhancing features via Project EPIC, modularly integrating them into specific use cases like portfolio tokenization. However, the overall Kinexys infrastructure has not migrated, instead adopting a “modular integration” approach within its existing architecture.

Intain operates its structured finance platform IntainMARKETS on Avalanche Subnet, supporting full on-chain automation of ABS issuance, investment, and settlement, currently managing over $6 billion in assets. Running on a permissioned network compliant with AML/KYC and GDPR, the platform enables multi-party participation and significantly reduces issuance costs and time for small-scale ABS, serving as a landmark case of blockchain success in structured finance.

In sum, bank-issued stablecoins are not just payment tools but can evolve into core infrastructure for compliant financial digitization. Connection to public chains should not be a near-term goal but pursued as a mid-to-long-term objective after regulatory alignment. Currently, a more realistic path is building infrastructure compatible with existing institutional finance in wholesale payments, securities clearing, and international liquidity management.

3.4. Korea’s Strategic Response

Korea’s policy environment does not prioritize speed in digital currency transformation but emphasizes institutional acceptability and policy control. Especially given the three policy pillars of monetary sovereignty, foreign exchange regulation, and financial stability, a gradual, bank- and central bank-led adoption strategy is required over private-sector-driven diffusion. Therefore, Korea’s strategic response follows three directions:

-

Foster Stablecoins Centered on Institutional Systems: Build permissioned infrastructure around bank-issued, deposit-backed stablecoins. Following global precedents, prioritize permissioned structures and limit Web3 partnerships through API or white-label integrations, striking a balance between stability and innovation.

-

Maintain Regulatory Sandboxes for Limited Flexibility: Allow non-bank entities to conduct limited experiments only within regulatory sandboxes, following detailed assessments of impacts on monetary policy effectiveness, capital flows, and financial stability. The primary goal is to maintain institutional capacity to respond to technological change.

-

Promote Global Alignment and Technical Standard Setting: Draw lessons from the Genius Act, EU MiCA, and Japan’s bank-led model to define distinct roles and interoperability standards among CBDC, deposit tokens, and private stablecoins. This ensures connective points between Korea’s institutional financial system and the global Web3 ecosystem, laying the foundation for a comprehensive digital payment system in the long run.

In conclusion, the bank-led, permissioned stablecoin model represents the most executable and institutionally acceptable digital currency strategy for Korea. It will form the technological foundation for future efficiencies in cross-border financial transactions, inter-institutional interoperability, and controlled circulation of digital assets. In contrast, non-bank issuance structures should remain confined to external experimentation, preserving the dual-structure model centered on the central bank and commercial banks.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News