Understanding Cysic: On the Eve of Hardware Acceleration and the Rise of ZK Mining

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Understanding Cysic: On the Eve of Hardware Acceleration and the Rise of ZK Mining

How will Cysic help realize the vision of mass adoption of ZK?

Author: Nickqiao & Wuyue, Geek Web3

In April this year, Vitalik visited the Hong Kong Blockchain Summit and delivered a speech titled "Reaching the Limits of Protocol Design," in which he once again highlighted the potential of ZK-SNARKs within Ethereum's Danksharding roadmap and expressed optimism about the significant role ASIC chips could play in accelerating ZK computations.

Previously, Zhang Ye, co-founder of Scroll, pointed out that the application space for ZK in traditional fields may be even larger than within Web3. Trusted computing, databases, verifiable hardware, content anti-counterfeiting, zkML, and other domains all exhibit substantial demand for ZK. If real-time generation of ZK proofs becomes feasible, both Web3 and traditional industries could undergo paradigm-shifting transformations. However, from the perspectives of efficiency and economic cost, widespread adoption of ZK remains distant.

As early as 2022, top-tier venture capital firms like a16z and Paradigm publicly released reports explicitly emphasizing the importance of ZK hardware acceleration. Paradigm even asserted that future ZK miners' revenues could rival those of Bitcoin or Ethereum miners, and that hardware acceleration solutions based on GPU, FPGA, and ASIC would occupy a massive market space. Since then, with the rising popularity of mainstream ZK Rollups such as Scroll and Starknet, hardware acceleration briefly became a hotly pursued concept, a trend further intensified by projects like Cysic approaching launch.

We have good reason to believe that given the vast demand for ZK, ZK mining pools and SaaS models for real-time ZKP generation can open up an entirely new industrial chain. In this promising landscape, ZK hardware manufacturers with strong capabilities and first-mover advantages could potentially become the next Bitmain, dominating the fertile ground of hardware acceleration.

Among hardware acceleration players, Cysic is likely one of the most closely watched contenders. The team has won major awards at ZPrize, a renowned ZKP technology competition platform, and since 2023 has served as a mentor for ZPrize. Its roadmap, featuring B2B ZK mining pools and consumer-facing ZK-DePIN hardware, has attracted investment from top-tier VCs including Polychain, ABCDE, OKX Ventures, and Hashkey, securing nearly $20 million in total funding.

With Cysic’s testnet set to launch by the end of July and its ZK mining pool soon to open, discussions around Cysic are gaining momentum across various communities. This article aims to help more people understand Cysic’s product principles and business model while offering a brief primer on ZK hardware acceleration. Below, we will provide a concise overview of Cysic-related knowledge to lower the barrier to understanding.

Understanding ZK Proof Systems Through Workflow

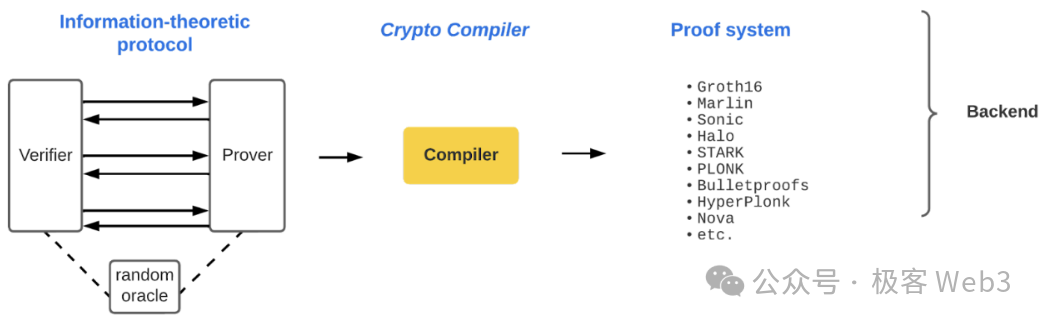

ZK proof systems are actually quite complex, but to gain a basic understanding of their overall structure, we can break them down by function and workflow. For a system that converts general computation into ZK-friendly formats, the core process can be summarized as follows:

First, we interact with the ZK system via a frontend interface, submitting the content to be proven. The frontend converts this content into a format suitable for processing by the ZK proof system. Then, the system uses specific proof frameworks (e.g., Halo2, Plonk) to generate a ZK proof. This process can be broken down into several steps:

1. Problem Setup: First, we define what needs to be proven. For example, a Prover claims to know certain data — “I know a solution N to the equation F(x)=w” — but does not want others to see the value of N.

2. Arithmetization and CSP: After the Prover submits the content to be proven, the system builds a dedicated mathematical model or program equivalent to the statement, then converts it into a format processable by the proof system. Specifically, the above claim — “I know a solution N to the equation F(x)=w” — is transformed from its original mathematical form into logic circuits and polynomial representations.

3. Next, the system selects an appropriate proof framework such as Halo or Plonk, compiling the outputs from earlier steps into executable ZKP programs. The Prover uses this program to generate a proof, which is then submitted to the Verifier for validation.

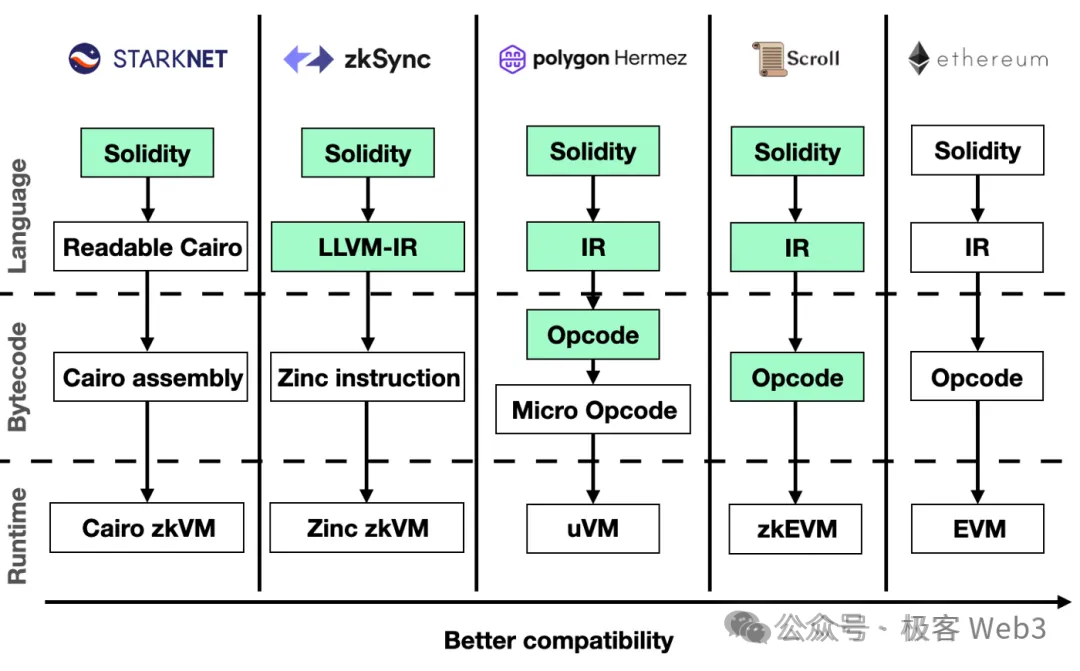

Systems like zkEVM, frequently adopted in Ethereum Layer 2 solutions, essentially compile smart contracts into low-level EVM opcodes, then convert each opcode into logic gates or polynomial constraints before handing them off to the backend ZK proof system for further processing.

Notably, the ZKP schemes widely used in blockchain today are primarily zk-SNARKs (Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge), and most ZK Rollups leverage SNARKs’ succinctness rather than their zero-knowledge property. Succinctness means ZKPs occupy very little space — compressing large amounts of data into just hundreds of bytes — resulting in extremely low verification costs.

Thus, there is an asymmetry between Prover and Verifier workloads: generating a ZKP is costly for the Prover, while verifying it is cheap for the Verifier. By leveraging this asymmetry in scenarios involving “one Prover, many Verifiers,” overall costs are concentrated on the Prover side, significantly reducing the burden on Verifiers. This model is highly favorable for decentralized verification, precisely the approach taken by Ethereum Layer 2 solutions.

However, shifting verification costs onto the ZK generation side is not a silver bullet. For ZK Rollup teams, the high cost of generating ZKPs will inevitably be passed on to user experience and transaction fees, which is detrimental to the long-term development of ZK Rollups.

Despite ZK’s great utility in trustless and decentralized verification settings, due to bottlenecks in generation time, neither zkEVM nor zkVM, nor ZK Rollups or ZK bridges currently have an economic foundation for mass adoption.

To address this, ZK acceleration projects such as Cysic, Ingonyama, and Irreducible have emerged, attempting from different angles to reduce the cost of ZKP generation. In the following sections, we will briefly introduce from a technical perspective the main computational overheads in ZKP generation and acceleration methods, and explain why Cysic holds significant potential in the ZK acceleration space.

Computational Overhead: MSM and NTT

Many people know that the time required for a ZKP Prover to generate a proof is extremely high. In ZK-SNARK protocols, it's common for a Verifier to verify a proof in just one second, while the Prover might spend half a day or even a full day generating it. To efficiently use ZKP-based computation, it's necessary to transform classical programs into ZK-friendly formats.

Currently, two approaches exist for achieving this: one is writing circuits using proof system frameworks like Halo2; the other involves using domain-specific languages (DSLs) such as Cairo or Circom to convert computations into intermediate representations for submission to proof systems. The proof system then generates ZK proofs based on these circuit designs or DSL-compiled intermediates.

The more complex the program operations, the longer it takes to generate a proof. Additionally, some operations are inherently ZK-unfriendly and require extra effort to implement. For instance, SHA or Keccak hash functions are ZK-unfriendly, and using them extends proof generation time. Even operations that are computationally inexpensive on classical computers can be inefficient in ZK contexts.

Setting aside ZK-unfriendly computations, although the ZK proof generation process may vary depending on the chosen proof system, the fundamental bottlenecks remain similar. In ZK proof generation, two types of computation consume the majority of resources: MSM (Multi-Scalar Multiplication) and NTT (Number Theoretic Transform). Together, they account for 80–95% of proof generation time, depending on the ZKP commitment scheme and implementation details.

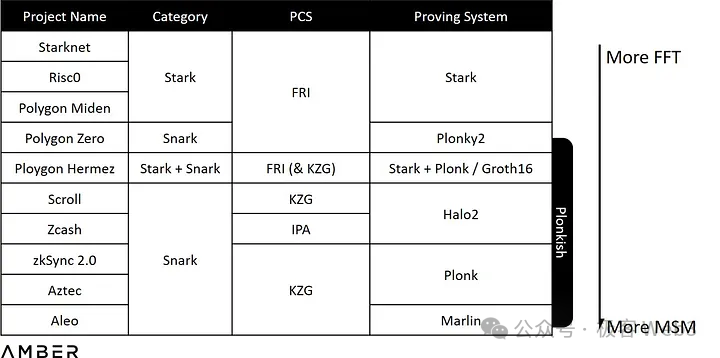

MSM mainly handles multi-scalar multiplication on elliptic curves, while NTT performs FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) over finite fields to accelerate polynomial multiplication. Different combinations of schemes lead to varying ratios of FFT/MSM workload.

Take Stark as an example: its PCS (Polynomial Commitment Scheme) uses FRI, a hash-based commitment, instead of elliptic curve-based schemes like KZG or IPA, so it involves no MSM computation at all. In the table below, higher positions indicate greater FFT computation requirements, while lower ones indicate heavier reliance on MSM.

Optimization Approaches

MSM operations involve predictable memory access patterns and can be highly parallelized, but they consume substantial memory resources. Moreover, MSM faces scalability challenges — even under parallelization, performance may still be slow. While MSM can be accelerated in hardware, doing so requires massive memory and parallel computing resources.

NTT often involves random memory access, making it hardware-unfriendly and difficult to handle in distributed infrastructures. Due to NTT’s random-access nature, running it in a distributed environment inevitably requires accessing data from other nodes, leading to significant performance degradation when network communication is involved.

Consequently, data access and movement become major bottlenecks, limiting NTT’s ability to scale in parallel. Most efforts to accelerate NTT focus on optimizing how computation interacts with memory.

In fact, the simplest way to solve the efficiency bottlenecks of MSM and NTT is to eliminate these operations entirely. Some newly proposed algorithms, such as Hyperplonk, modify Plonk to remove NTT operations, making Hyperplonk easier to accelerate, though introducing new bottlenecks such as the computationally expensive sumcheck protocol. Similarly, the STARK algorithm avoids MSM altogether but introduces extensive hashing through its FRI protocol.

ZK Hardware Acceleration and Cysic’s Ultimate Goal

Although software and algorithmic optimizations are important and valuable, they have clear limitations. To fully optimize ZKP generation efficiency, hardware acceleration is essential — just as ASICs and GPUs eventually dominated BTC and ETH mining markets.

So the question arises: what is the best hardware for accelerating ZKP generation? Currently, multiple hardware options exist — GPU, FPGA, or ASIC — each with distinct advantages and trade-offs.

Let us compare these hardware types:

Let’s illustrate their differences at the development level with a simple example: suppose we want to implement a basic parallel multiplication:

-

On a GPU, using APIs provided by CUDA SDK, we can develop code almost natively, gaining access to parallel computing power;

-

On an FPGA, we must learn hardware description languages and use them to control low-level hardware connections to implement parallel algorithms;

-

On an ASIC, transistor interconnects are fixed during chip design and cannot be modified afterward.

Each of these solutions has strengths suited to different stages of ZK ecosystem development. Cysic aims to become the ultimate solution for ZK hardware acceleration, pursuing a phased strategy:

-

Develop SDKs based on GPU to provide solutions for ZK applications and integrate global GPU resources;

-

Leverage FPGA’s flexibility and balanced characteristics to rapidly deliver customized ZK hardware acceleration;

-

Independently develop ASIC-based ZK DePIN hardware;

-

Cysic Network will act as a SaaS platform/mining pool, integrating all compute power from ZK DePIN and GPUs to provide comprehensive compute and verification solutions for the entire ZK industry.

Next, let’s examine multiple specialized sectors in detail to fully grasp the nuances among ZK acceleration approaches and Cysic’s strategic vision.

ZK Mining Pools and SaaS Platforms: Cysic Network

In fact, well-known ZK Rollups like Scroll and Polygon zkEVM have both explicitly mentioned the concept of a “decentralized Prover” in their roadmaps — essentially building ZK mining pools. This market-driven approach allows ZK Rollup teams to offload operational burdens and incentivizes miners and pool operators to continuously optimize ZK acceleration techniques.

Cysic’s roadmap clearly outlines plans for Cysic Network — a ZK mining pool and SaaS platform. It will not only integrate Cysic’s own computing power but also absorb third-party resources through mining incentives, including idle GPUs and ZK DePIN devices owned by regular users.

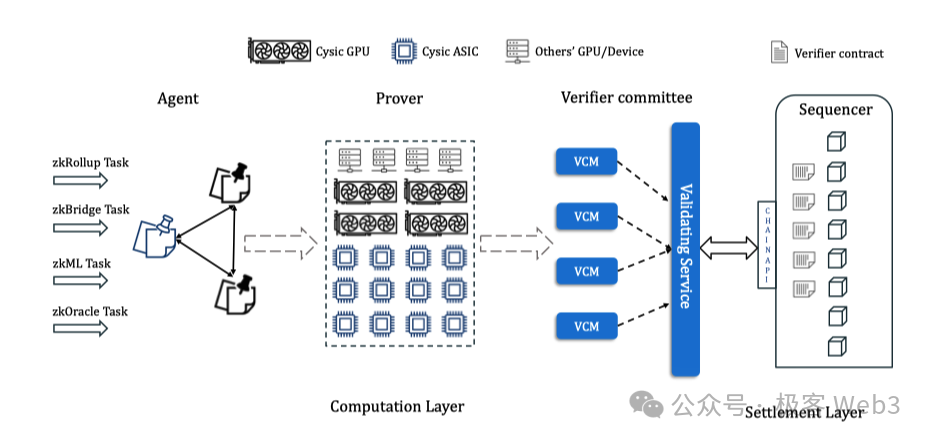

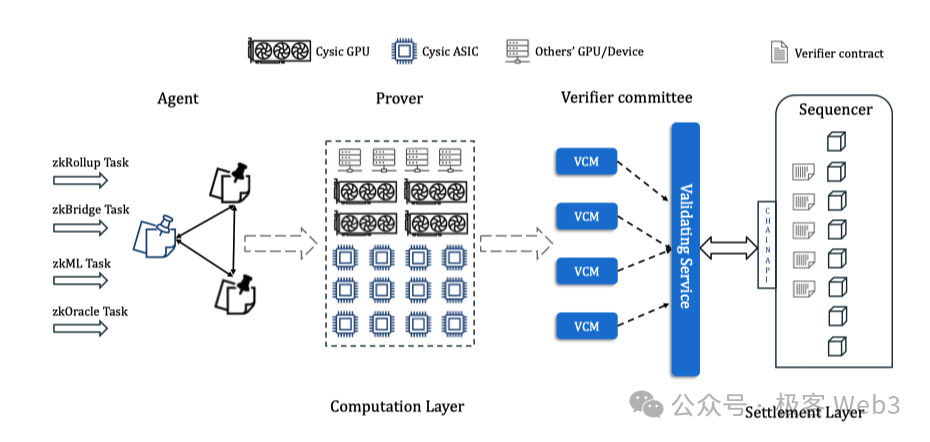

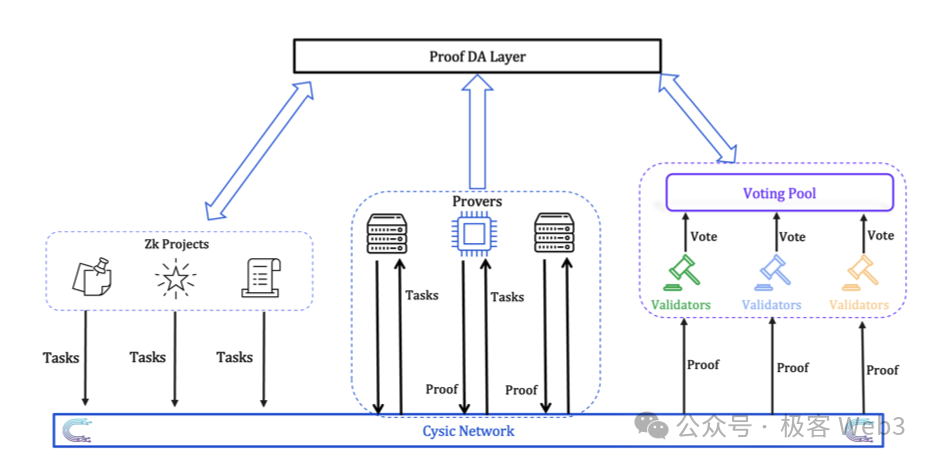

The overall workflow diagram is as follows:

-

ZK project teams submit proof-generation tasks to Agents, whose role is to forward these tasks to the validation network. Initially operated by Cysic, these Agents will later require asset staking, allowing anyone to become an Agent;

-

-

Provers accept proof tasks and use hardware to generate ZK proofs. They must stake tokens to participate in task execution and receive rewards upon completion;

-

-

A committee of Validators checks the validity of proofs generated by Provers and votes accordingly. Once a threshold is reached, the proof is deemed valid. Validators join the committee by staking tokens, participate in voting, and earn rewards. This process can integrate EigenLayer’s AVS concept, reusing existing restaking infrastructure.

The detailed interaction flow is shown below:

One point in the above process is that actions such as asset staking, incentive distribution, and task submission all depend on a dedicated platform, requiring a blockchain as underlying infrastructure.

To this end, Cysic Network has built a dedicated public chain using a unique consensus mechanism called Proof of Compute (PoC). Its basic principle leverages VRF functions and historical performance metrics of Provers — such as device availability, number of submitted proofs, and proof correctness rate — to select block producers (Note: These blocks likely record device information and distribute token incentives).

Of course, beyond ZK mining pools and SaaS platforms, Cysic has made extensive investments across ZK acceleration solutions using different hardware. Let’s now explore its achievements along the GPU, FPGA, and ASIC paths.

GPU, FPGA, and ASIC

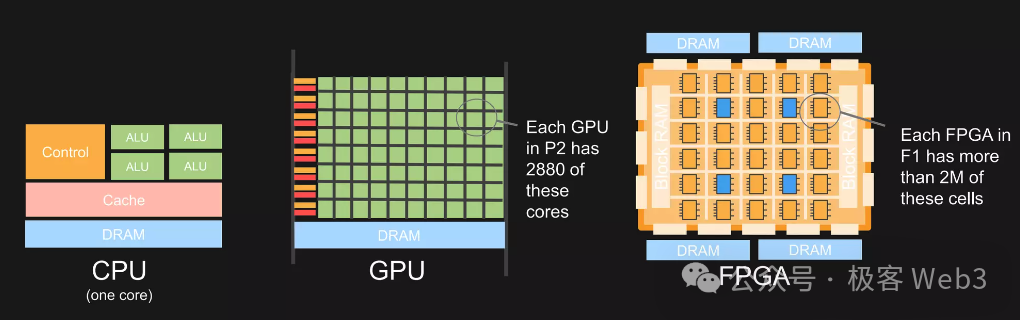

The core of ZK hardware acceleration lies in maximizing parallelization of key computations. From a functional standpoint, CPUs prioritize maximum flexibility and generality, dedicating much of their chip area to control logic and multiple levels of cache, resulting in weak parallel computing capability.

GPUs dramatically increase the proportion of chip area devoted to computation, enabling large-scale parallel processing. GPUs are now widely available; libraries like Nvidia CUDA allow developers to harness GPU parallelism without needing to understand the underlying hardware. CUDA SDKs can encapsulate CUDA ZK libraries to accelerate MSM and NTT operations.

FPGAs consist of arrays of numerous small processing units. Programming FPGAs requires specialized hardware description languages, which are compiled into transistor-level circuit configurations. Thus, FPGAs directly implement specific algorithms via transistor circuits, bypassing instruction-set compilation. This offers far greater customization and flexibility compared to GPUs.

Currently, FPGA prices are roughly one-third of GPU costs, and energy efficiency can exceed GPUs by tenfold or more. This significant efficiency advantage partly stems from GPUs requiring connection to host devices, which typically consume substantial power. Effectively, FPGAs can add more computational modules without increasing energy consumption, meeting the demands of MSM and NTT. This makes FPGAs particularly suitable for ZK proof scenarios requiring intensive computation, high data throughput, and low latency.

However, the biggest challenge with FPGAs is the scarcity of developers with relevant programming experience. For ZK project teams, assembling a group possessing both cryptographic expertise and FPGA engineering skills is extremely difficult.

ASICs, on the other hand, represent complete hardware implementations of specific programs. Once designed, the hardware cannot be altered, meaning the ASIC can only perform its designated task. The hardware acceleration benefits FPGAs offer for MSM and NTT are also present in ASICs. Due to dedicated circuit design, ASICs deliver the highest performance and lowest power consumption among all solutions.

For current mainstream ZK circuits, Cysic aims to achieve proof generation times of 1–5 seconds — a goal attainable only with ASICs.

While these advantages sound highly appealing, ZK technology is evolving rapidly, whereas ASIC design and production cycles typically take 1–2 years and cost $10–20 million. Therefore, ZK technology must stabilize sufficiently before mass production to avoid obsolescence of manufactured chips.

In response, Cysic has made comprehensive moves across GPU, FPGA, and ASIC domains:

In GPU acceleration, Cysic has adapted its proprietary CUDA acceleration SDK to accommodate various emerging ZK proof systems. By aggregating community resources, Cysic’s GPU compute network links hundreds of thousands of top-tier graphics cards. Furthermore, Cysic’s CUDA SDK outperforms the latest open-source frameworks by 50%–80% or more.

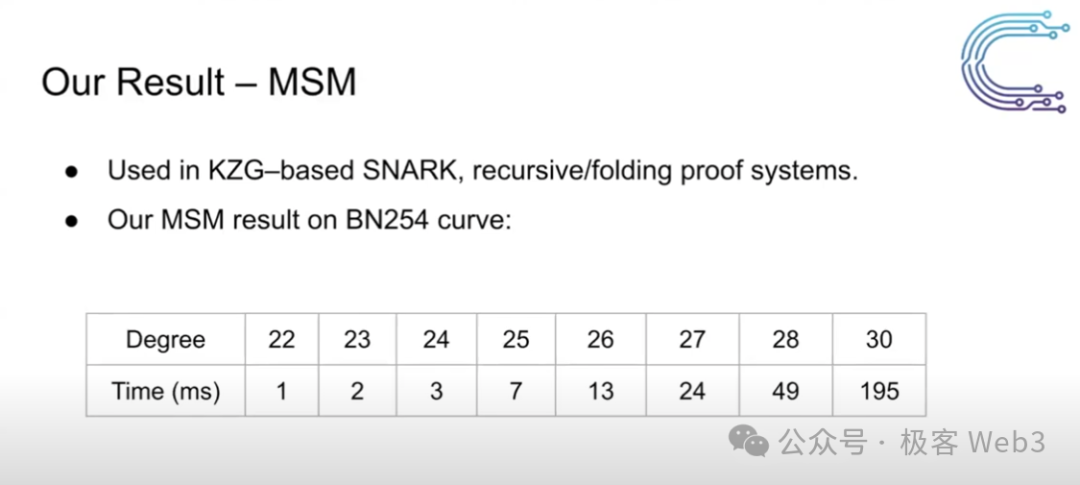

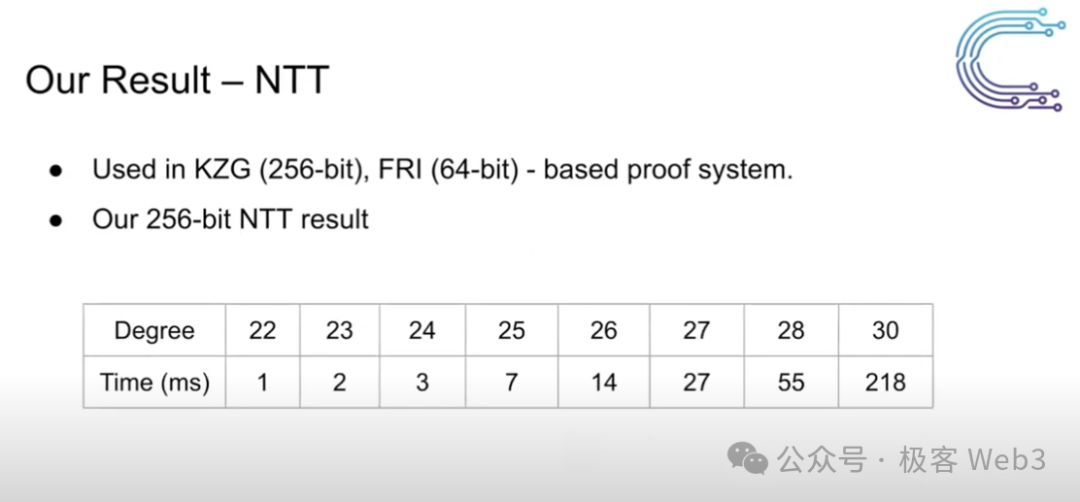

In FPGA development, Cysic has achieved the world’s fastest implementations of critical modules such as MSM, NTT, and Poseidon Merkle trees — covering the core components of ZK computation — and validated these designs through prototypes in multiple leading ZK projects.

Cysic’s self-developed SolarMSM completes 2^30-scale MSM calculations in 0.195 seconds, while SolarNTT finishes 2^30-scale NTT calculations in 0.218 seconds — the highest performance among all publicly disclosed FPGA hardware acceleration results to date.

In the ASIC domain, although large-scale application of ZK ASICs remains some distance away, Cysic has already begun positioning itself in this space and has launched self-developed ZK DePIN chips and devices.

To attract end consumers and meet diverse performance and cost requirements from different ZK projects, Cysic will launch two ZK hardware products: ZK Air and ZK Pro.

ZK Air is about the size of a power bank or laptop charger. Ordinary users can connect it directly via Type-C to laptops, iPads, or even smartphones, providing computational support for specific ZK projects and earning rewards. Currently, ZK Air’s computing power already surpasses consumer-grade GPUs, capable of accelerating small-scale ZK proof generation tasks.

ZK Pro resembles traditional mining rigs, delivering computing power comparable to multi-GPU servers built from top-tier consumer graphics cards. It enables dramatic acceleration of ZK proof generation, suitable for large-scale ZK projects such as ZK-Rollups and ZKML (Zero-Knowledge Machine Learning).

Through these two devices, Cysic will ultimately build a stable and reliable ZK-DePIN network. Both products are currently under development and expected to launch in 2025.

Additionally, through Cysic Network, individual users can enter the ZK hardware acceleration market with minimal barriers. Combined with the substantial demand for compute power from ZK projects, this could spark another wave of enthusiasm akin to Bitcoin mining, potentially triggering explosive growth in the ZK computing market.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News