Author: @Web3Mario

Introduction: On May 13, 2024, Vitalik published EIP-7706, proposing a supplementary solution to Ethereum's existing gas model. The proposal separates the gas calculation for calldata and introduces a base fee pricing mechanism similar to blob gas, further reducing L2 operational costs. Related proposals trace back to EIP-4844 introduced in February 2022—so long ago that reviewing relevant materials provides a comprehensive overview of Ethereum’s latest gas mechanisms, enabling readers to quickly grasp the updates.

Currently Supported Ethereum Gas Models — EIP-1559 and EIP-4844

Initially, Ethereum used a simple auction mechanism to price transaction fees, requiring users to manually set a gas price for their transactions. Typically, since miners received these fees as rewards, they prioritized transactions with higher bids when selecting which to include in blocks—this assumes no MEV considerations. However, core developers identified four major issues with this approach:

l Mismatch between volatile transaction fees and consensus cost: On active blockchains where demand for block space is high, blocks are easily filled, but this often leads to extreme volatility in transaction fees. For example, if the average gas price rises from 1 Gwei to 10 Gwei, the marginal cost of adding one more transaction increases tenfold—an unacceptable fluctuation.

l Unnecessary delays for users: Due to the hard gas limit per block and natural fluctuations in transaction volume, transactions frequently wait multiple blocks before being confirmed. This inefficiency stems from the lack of a "sliding window" mechanism allowing some blocks to be larger while others are smaller, adapting dynamically to varying demand.

l Inefficient price discovery: The simple auction model results in poor market efficiency, making it difficult for users to estimate fair prices, often leading them to overpay significantly.

l Instability without block rewards: Transitioning to a pure fee-based model (removing block rewards) could destabilize the network—for instance, incentivizing miners to create competing “sister blocks” to steal fees or enabling stronger selfish mining attacks.

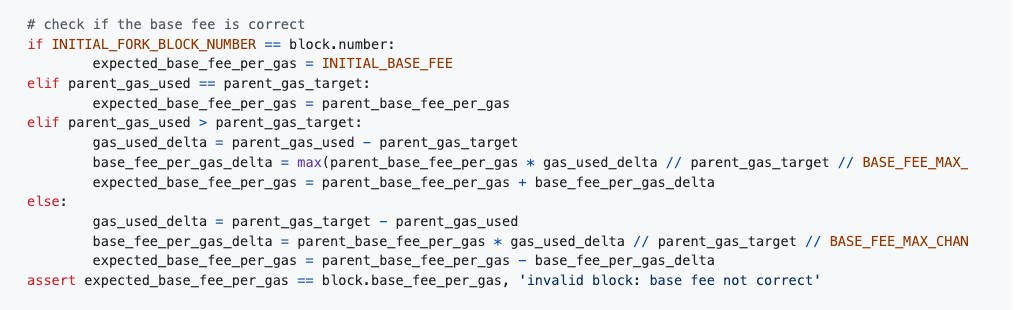

The first major iteration came with EIP-1559, proposed by Vitalik and other core developers on April 13, 2019, and implemented during the London upgrade on August 5, 2021. It replaced the auction system with a dual-pricing model composed of a base fee and a priority fee. The base fee adjusts algorithmically based on the difference between actual gas usage in the parent block and a dynamic gas target. If gas usage exceeds the target, the base fee increases; otherwise, it decreases. This better reflects supply-demand dynamics and enables more predictable fee estimation, eliminating risks of accidental overpayment due to user misconfiguration. The formula is shown below:

As shown, when parent_gas_used exceeds parent_gas_target, the current block’s base fee increases by an offset value derived from multiplying parent_base_fee by the ratio of excess gas usage relative to the gas target, divided by a constant denominator, capped at a minimum factor of 1. The reverse logic applies when usage falls short.

Notably, the base fee is burned rather than paid to miners, placing ETH under a deflationary economic model that supports long-term value stability. Meanwhile, the priority fee acts like a tip to miners, freely set by users, preserving some flexibility in miner incentives and transaction ordering.

By 2021, Rollup technologies were gaining momentum. Both OP Rollups and ZK Rollups require compressing L2 data and submitting proofs via calldata to achieve data availability (DA) or on-chain verification. This imposes significant gas costs on L2 protocols when finalizing state, costs ultimately passed down to end users. As a result, most L2 solutions remained far more expensive than anticipated.

At the same time, Ethereum faced increasing competition for block space. Each block has a gas limit—currently 30,000,000—meaning total gas consumption across all transactions cannot exceed this cap. Given that each calldata byte consumes 16 gas units, this implies a theoretical maximum of 30,000,000 / 16 = 1,875,000 bytes (~1.79 MB) per block. Since rollup sequencers generate large volumes of data, they compete directly with regular mainnet transactions, reducing available space for ordinary transactions and negatively impacting Ethereum’s overall TPS.

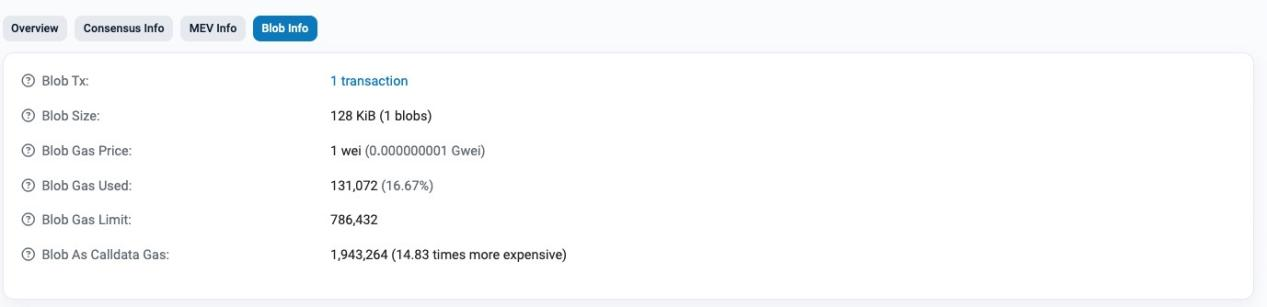

To address this, core developers introduced EIP-4844 on February 5, 2022, later implemented in Q2 2024 during the Dencun upgrade. This proposal introduced a new transaction type—Blob Transactions—which adds a new data structure called blob data. Unlike calldata, blob data cannot be accessed directly by the EVM; only its hash (called a VersionedHash) is accessible. Two key design elements accompany this change: First, blob data has a shorter garbage collection (GC) period, preventing excessive blockchain bloat. Second, blob data uses a native gas mechanism inspired by EIP-1559 but employing a natural exponential function for base fee adjustments, enhancing responsiveness and stability during traffic surges. Because the derivative of an exponential function is itself exponential, the fee reacts more sharply during sudden spikes, effectively curbing congestion. Additionally, the function ensures a base value of 1 when the input is zero.

base_fee_per_blob_gas = MIN_BASE_FEE_PER_BLOB_GAS * e**(excess_blob_gas / BLOB_BASE_FEE_UPDATE_FRACTION)

Here, MIN_BASE_FEE_PER_BLOB_GAS and BLOB_BASE_FEE_UPDATE_FRACTION are constants, while excess_blob_gas equals the difference between total blob gas consumed in the parent block and TARGET_BLOB_GAS_PER_BLOCK. When consumption exceeds the target (positive difference), the exponentiation yields a multiplier greater than 1, increasing the base fee; otherwise, it decreases.

This allows low-cost submission of large datasets relying solely on Ethereum’s consensus layer for data availability, without congesting traditional transaction capacity. For example, rollup sequencers can encapsulate critical L2 information into blob data and use versioned hashes within EVM contracts to verify inclusion efficiently.

It should be noted that current settings for TARGET_BLOB_GAS_PER_BLOCK and MAX_BLOB_GAS_PER_BLOCK impose constraints: an average of 3 blobs (0.375 MB) per block, up to a maximum of 6 blobs (0.75 MB). These initial limits aim to minimize network strain, with expectations that they will increase in future upgrades as the network proves reliable under larger loads.

Refining the Execution Environment Gas Model — EIP-7706

Having clarified Ethereum’s current gas models, we now examine the goals and implementation details of EIP-7706, proposed by Vitalik on May 13, 2024. Similar to blob data, this proposal isolates the gas model for another uniquely characterized data field: calldata. It also refines the underlying code logic accordingly.

In principle, the base fee calculation for calldata mirrors that of blob data in EIP-4844—both use an exponential function scaled by the deviation of actual gas usage from a target in the parent block.

A notable addition is a new parameter: LIMIT_TARGET_RATIOS=[2,2,4], where LIMIT_TARGET_RATIOS[0] represents the target ratio for execution-type gas, LIMIT_TARGET_RATIOS[1] for blob data gas, and LIMIT_TARGET_RATIOS[2] for calldata gas. This vector determines the gas targets for each category by dividing the respective gas limits:

The gas_limits are defined as follows:

gas_limits[0] must follow the existing adjustment formula

gas_limits[1] must equal MAX_BLOB_GAS_PER_BLOCK

gas_limits[2] must equal gas_limits[0] // CALLDATA_GAS_LIMIT_RATIO

Given that gas_limits[0] is currently 30,000,000 and CALLDATA_GAS_LIMIT_RATIO is preset to 4, the calldata gas target becomes approximately 30,000,000 // 4 // 4 = 1,875,000. Considering the current calldata pricing—16 gas per non-zero byte, 4 gas per zero byte—and assuming a 50/50 distribution of zero and non-zero bytes, the average cost per byte is about 10 gas. Thus, the calldata gas target corresponds to roughly 187,500 bytes of calldata—about twice the current average usage.

This design greatly reduces the likelihood of hitting the calldata gas limit, using economic incentives to maintain stable and sustainable calldata usage while discouraging abuse. Ultimately, this aims to remove barriers for L2 development, working alongside blob data to further reduce sequencer costs.