In-Depth Analysis of Parallel EVM: How to Break Through Blockchain Performance Bottlenecks?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

In-Depth Analysis of Parallel EVM: How to Break Through Blockchain Performance Bottlenecks?

Parallel EVM is a new narrative that emerged as on-chain transaction volume reached a certain level.

Author: @leesper6

Advisor: @CryptoScott_ETH

TL;DR

-

Parallel EVM is a new narrative that emerged as on-chain transaction volume reached a certain level. Parallel EVM primarily consists of monolithic blockchains and modular blockchains. Monolithic blockchains are further divided into L1 and L2. Parallel L1 public chains fall into two major camps: EVM and non-EVM. Currently, the parallel EVM narrative is still in its early development stage;

-

The technical implementation of parallel EVM can be broken down into two main aspects: virtual machines and parallel execution mechanisms. In the context of blockchain, a virtual machine refers to a process virtual machine that virtually simulates a distributed state machine for executing smart contracts;

-

Parallel execution means leveraging multi-core processors to execute multiple transactions simultaneously whenever possible, while ensuring the final state matches the result of sequential execution;

-

Parallel execution mechanisms are categorized into three types: message passing, shared memory, and strict state access lists. Shared memory is further subdivided into memory lock models and optimistic parallelization. All these mechanisms increase technical complexity;

-

The parallel EVM narrative is driven by both internal industry growth factors and requires close attention to potential security risks;

-

Each project in the parallel EVM space offers unique approaches to parallel execution, sharing common technical foundations while also making their own distinctive contributions.

1. Industry Overview

1.1 Historical Evolution

Performance has become a bottleneck for further industry development. Blockchain networks have created a new decentralized trust foundation for individuals and enterprises to conduct transactions.

Represented by Bitcoin, the first generation of blockchain networks pioneered a decentralized electronic currency transaction model through distributed ledger technology, revolutionizing the era. The second generation, represented by Ethereum, fully embraced imagination by proposing decentralized applications (dApps) via distributed state machines.

Since then, blockchain networks have undergone rapid development over more than a decade, spawning countless innovations in technology and business models—from Web3 infrastructure to various sectors like DeFi, NFTs, social networks, and GameFi. The thriving industry continuously attracts new users to participate in dApp ecosystem building, which in turn demands higher product experience standards.

As a completely novel product form, Web3 must not only innovate in meeting user needs (functional requirements) but also balance security and performance (non-functional requirements). Since its inception, numerous solutions have been proposed to address performance issues.

These solutions can be broadly categorized into two groups: on-chain scaling solutions such as sharding and directed acyclic graphs (DAG), and off-chain scaling solutions such as Plasma, Lightning Network, sidechains, and Rollups. However, these have failed to keep pace with the rapidly growing volume of on-chain transactions.

Especially after the 2020 DeFi Summer and the sustained explosion of inscriptions in the Bitcoin ecosystem at the end of 2023, the industry urgently needs new performance enhancement solutions to meet the "high-performance, low-fee" requirements. Parallel blockchains were born under this backdrop.

1.2 Market Size

The parallel EVM narrative marks the emergence of a duopoly in the parallel blockchain domain. Ethereum processes transactions sequentially—one after another—resulting in low resource utilization. Converting this serial processing into parallel processing would bring massive performance gains.

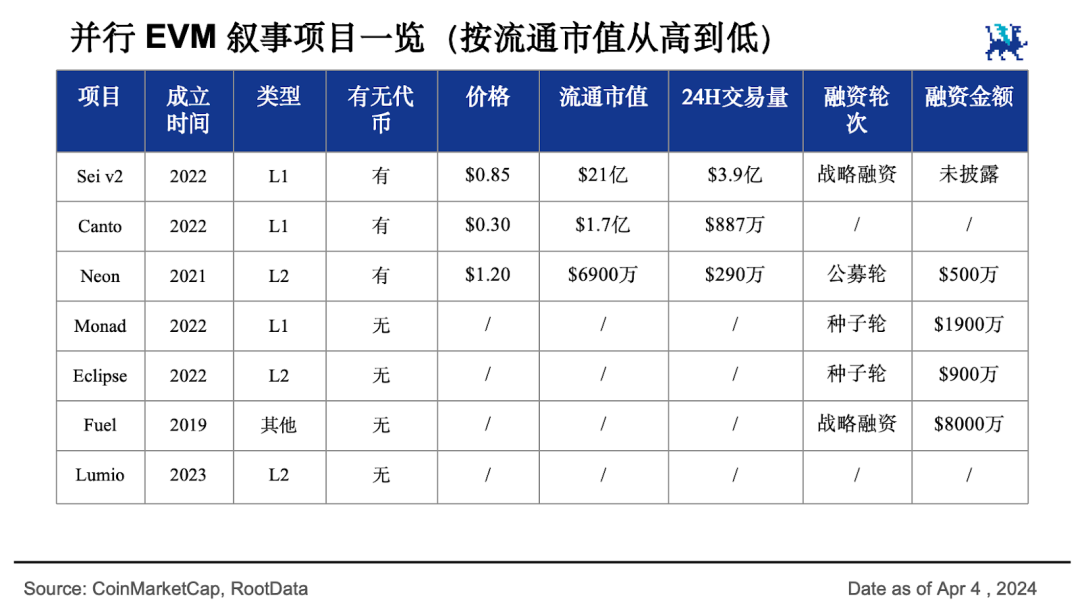

Ethereum competitors such as Solana, Aptos, and Sui all come with built-in parallel processing capabilities and have developed strong ecosystems, with circulating market caps reaching $45 billion, $3.3 billion, and $1.9 billion respectively—forming the parallel non-EVM camp. In response, the Ethereum ecosystem has stepped up, empowering EVM with parallel capabilities and forming the parallel EVM camp.

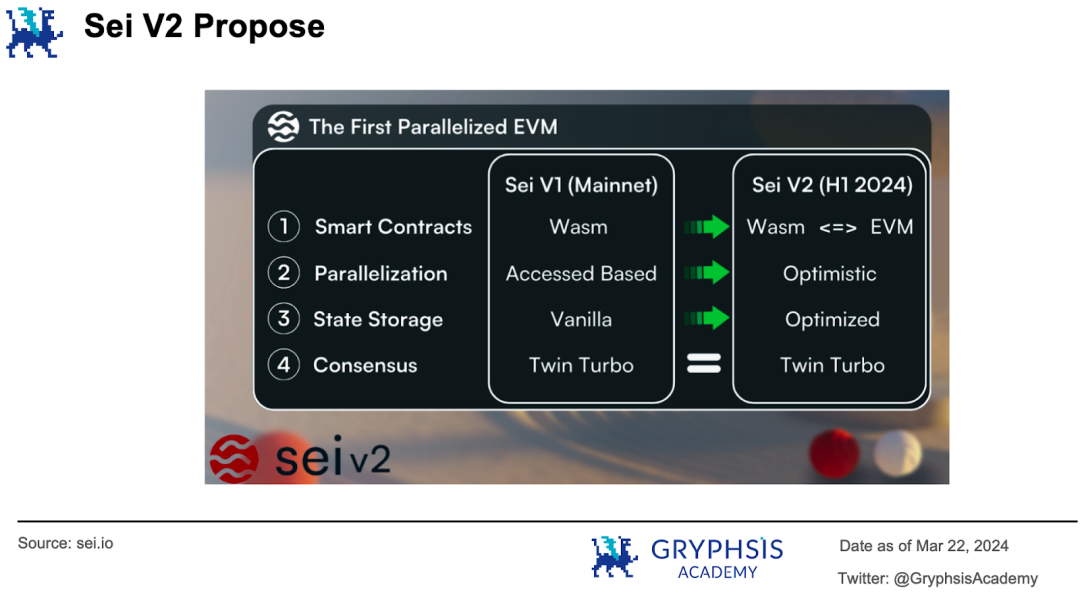

Sei boldly declared in its v2 upgrade proposal that it will become the "first parallel EVM blockchain," currently with a circulating market cap of $2.1 billion and significant future potential. Monad, the most hyped parallel EVM new public chain in marketing, is highly favored by capital and holds considerable promise. Canto, an L1 public chain with a $170 million market cap and free public infrastructure, has also announced its parallel EVM upgrade proposal.

In addition, a number of early-stage L2 projects are providing cross-ecosystem performance improvements by integrating capabilities from multiple L1 chains. Aside from Neon achieving a $69 million circulating market cap, other projects lack relevant data. More L1 and L2 projects are expected to join the parallel blockchain battlefield in the future.

Not only does the parallel EVM narrative have substantial room for market growth, but the broader parallel blockchain sector also holds vast potential, indicating a bright market outlook.

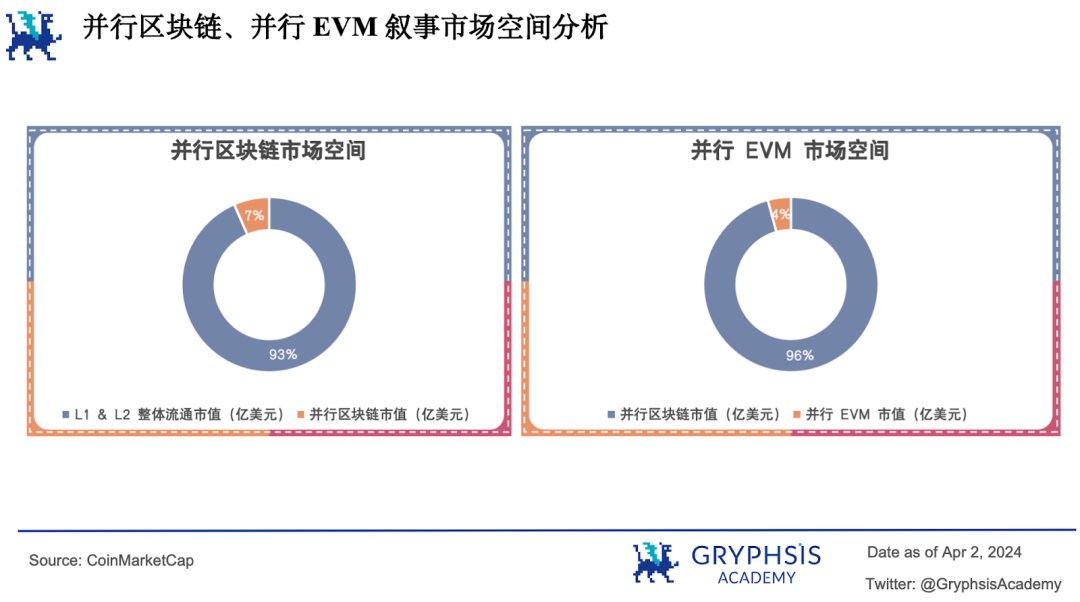

Currently, the total circulating market cap of L1 and L2 is $752.123 billion, while the parallel blockchain segment stands at $52.539 billion—only about 7%. Within that, parallel EVM-related projects amount to $2.339 billion, just 4% of the parallel blockchain market cap.

1.3 Industry Landscape

The industry generally divides blockchain networks into four layers:

-

Layer 0 (Network): The underlying blockchain network handling basic network communication protocols

-

Layer 1 (Infrastructure): Decentralized networks relying on various consensus mechanisms to validate transactions

-

Layer 2 (Scaling): Layer 2 protocols dependent on Layer 1, designed to solve limitations of Layer 1, especially scalability

-

Layer 3 (Application): Built atop Layer 2 or Layer 1 to support various decentralized applications (dApps)

Parallel EVM projects are mainly divided into monolithic blockchains and modular blockchains, with monolithic blockchains further split into L1 and L2. From the number of projects and key sector developments, parallel EVM L1 ecosystems still have considerable room to grow compared to Ethereum's.

DeFi demands "high speed and low fees," while gaming requires "strong real-time interaction"—both need faster execution speeds. Parallel EVM will inevitably enhance user experience for these projects and propel the industry into a new phase.

L1 refers to new public chains with native parallel execution capability—high-performance infrastructure. In this category, projects like Sei v2, Monad, and Canto design their own parallel EVMs, compatible with the Ethereum ecosystem while offering high-throughput transaction processing.

L2 enhances scalability through integration of multiple L1 capabilities, representing the cutting edge of rollup technology. In this group, Neon is an EVM emulator on the Solana network, Eclipse executes transactions on Solana but settles on EVM. Lumio is similar to Eclipse, except it uses Aptos as the execution layer.

Beyond these monolithic blockchain solutions, Fuel proposes its own modular blockchain approach. In its second version, it positions itself as an Ethereum rollup operating system, delivering more flexible and thorough modular execution capabilities.

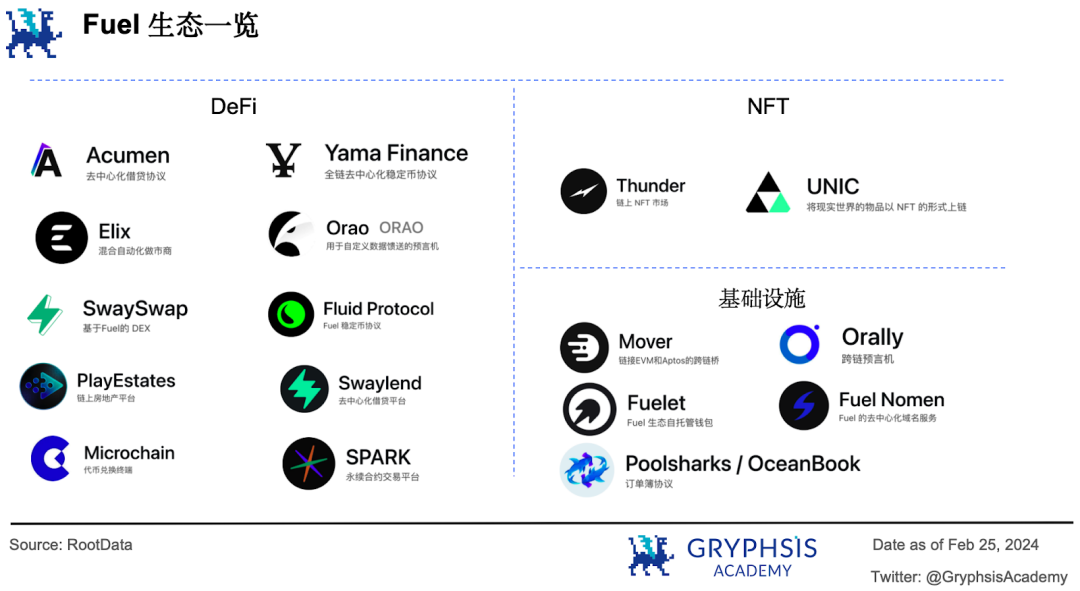

Fuel focuses solely on transaction execution, outsourcing other components to one or more independent blockchain layers, enabling flexible combinations—it can function as an L2, an L1, or even a sidechain or state channel. Currently, Fuel’s ecosystem includes 17 projects, concentrated in DeFi, NFTs, and infrastructure.

However, only Orally, a cross-chain oracle, has been deployed in production. The decentralized lending platform Swaylend and perpetual trading platform SPARK are on testnet, while others remain in development.

2. Technical Implementation Pathways

To achieve decentralized transaction execution, a blockchain network must fulfill four responsibilities:

-

Execution: Execute and validate transactions

-

Data Availability: Distribute new blocks to all nodes in the network

-

Consensus: Validate blocks and reach agreement

-

Settlement: Finalize and record the transaction state

Parallel EVM primarily optimizes performance at the execution layer. This includes both Layer 1 (L1) and Layer 2 (L2) solutions. L1 solutions introduce parallel transaction execution mechanisms to maximize concurrent execution within the virtual machine. L2 solutions essentially leverage already-parallelized L1 virtual machines to achieve a form of "off-chain execution with on-chain settlement."

Therefore, to understand the technical principles of parallel EVM, we must break it down: first understanding what a virtual machine (virtual machine) is, then what parallel execution (parallel execution) entails.

2.1 Virtual Machine

In computer science, a virtual machine refers to the virtualization or emulation of a computer system.

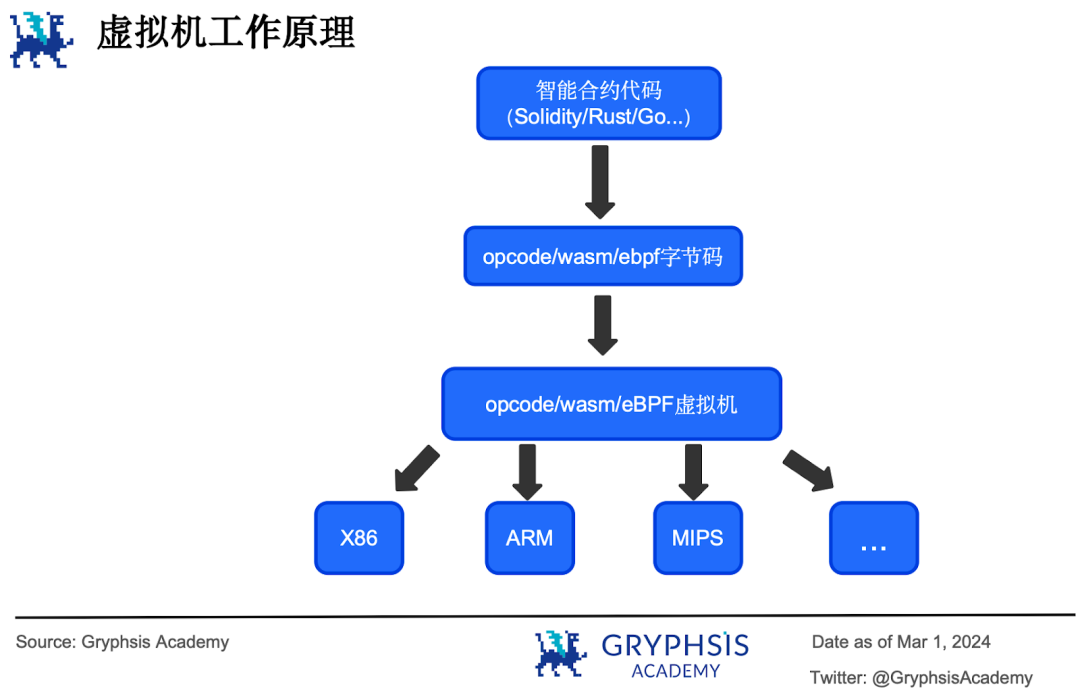

There are two types of virtual machines: system virtual machines (system virtual machine), which virtualize a physical machine into multiple machines running different operating systems to improve resource utilization; and process virtual machines (process virtual machine), which provide abstractions for certain high-level programming languages, allowing programs written in those languages to run platform-independently across different environments.

JVM is a process virtual machine designed for the Java programming language. Java programs are first compiled into Java bytecode (an intermediate binary format), which is then interpreted and executed by the JVM: the JVM sends bytecode to an interpreter, which translates it into machine code for different platforms before execution.

Blockchain virtual machines are a type of process virtual machine. In the blockchain context, a virtual machine refers to the virtualization of a distributed state machine, used for distributed contract execution and dApp operation. Analogous to JVM, EVM is a process virtual machine designed for Solidity, where smart contracts are first compiled into opcode bytecode and then interpreted and executed by the EVM.

Emerging public chains outside Ethereum often implement virtual machines based on WASM or eBPF bytecode. WASM is a compact, fast-loading, portable bytecode format with sandbox-based security, allowing developers to write smart contracts in multiple languages (C, C++, Rust, Go, Python, Java, even TypeScript), compile them into WASM bytecode, and execute them. Smart contracts on the Sei chain use exactly this bytecode format.

eBPF originated from BPF (Berkeley Packet Filter), initially used for efficient network packet filtering, later evolving into eBPF with richer instruction sets.

It is a revolutionary technology enabling dynamic intervention and modification of kernel behavior without changing source code. Later, this technology extended beyond the kernel, developing user-space eBPF runtimes with high performance, security, and portability. Smart contracts on Solana are compiled into eBPF bytecode and executed on its blockchain network.

Other L1 chains: Aptos and Sui use the Move smart contract programming language, compiling into proprietary bytecode executed on the Move VM. Monad designed its own virtual machine compatible with EVM opcode bytecode (Shanghai fork).

2.2 Parallel Execution

Parallel execution is a technique that:

-

Leverages multi-core processors to handle multiple tasks simultaneously, increasing system throughput;

-

Ensures the resulting transaction outcomes are identical to those achieved through sequential execution.

Blockchains commonly use TPS (transactions per second) as a metric for processing speed. Parallel execution mechanisms are complex and demand high developer expertise, making them difficult to explain clearly. Below, we use a "bank" example to illustrate what parallel execution means.

(1) What is sequential execution?

Scenario 1: If we view the system as a bank and the CPU processing tasks as tellers, sequential task execution is like having only one counter open. Customers (tasks) arriving at the bank must line up in a single queue, waiting their turn. Each teller repeats the same actions (executing instructions) for each customer. While not their turn, customers wait idly, causing longer transaction times.

(2) Then what is parallel execution?

Scenario 2: Seeing overcrowding, the bank opens additional counters—four tellers now serve customers simultaneously, speeding up service by roughly four times. Customer wait times reduce to about a quarter, significantly improving overall efficiency.

(3) Without safeguards, what errors occur when two people transfer money to a third simultaneously?

Scenario 3: Three individuals—A, B, and C—have 2 ETH, 1 ETH, and 0 ETH respectively. A and B each want to send 0.5 ETH to C. In a sequentially executing system, no issues arise (left arrow "<=" indicates reading the ledger, right arrow "=>" indicates writing to the ledger, same below):

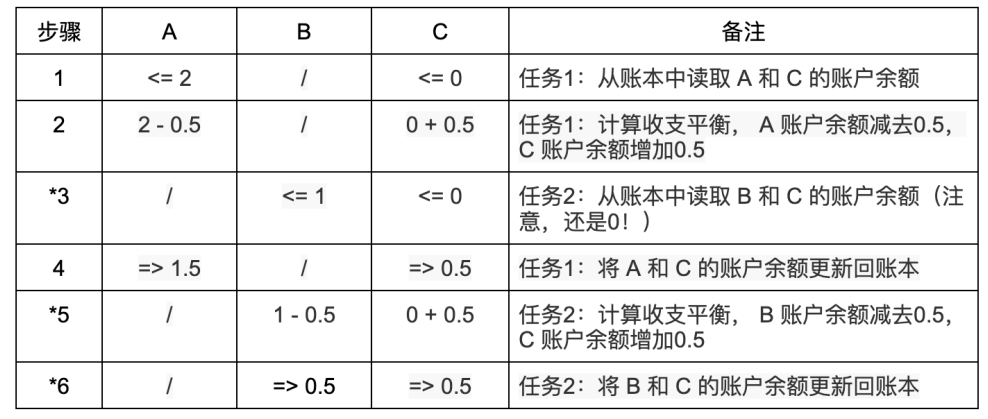

But parallel execution isn't as simple as it seems. Subtle details can lead to severe errors. If A and B's transfers to C are executed in parallel, the outcome may differ depending on execution order:

Parallel Task 1 executes A→C transfer, Parallel Task 2 executes B→C transfer. Steps marked with * are problematic: because tasks run in parallel, during Step 2, Task 1 hasn't yet written its updated balance to the ledger; during Step 3, Task 2 reads C's balance as 0, then in Step 5 performs incorrect accounting based on balance=0, finally overwriting the correct balance of 0.5 (from Step 4) back to 0.5 in Step 6. As a result, although both A and B transferred 0.5 ETH to C, C ends up with only 0.5 ETH—the other 0.5 ETH disappears.

(4) Without safeguards, parallel execution of two independent tasks causes no error

Scenario 4: Parallel Task 1 executes A (2 ETH) sending 0.5 ETH to C (0 ETH), Parallel Task 2 executes B (1 ETH) sending 0.5 ETH to D (0 ETH). These two transactions have no dependency. Regardless of execution interleaving, no such errors occur:

By comparing the two scenarios, we conclude: if tasks have dependencies, parallel execution may cause state update errors; otherwise, no errors occur. Two conditions define task dependencies:

-

One task writes to an address that another task reads;

-

Two tasks write to the same address.

This isn't unique to decentralization. Any parallel execution scenario involving multiple dependent tasks accessing shared resources unprotected (the "ledger" in the bank example, shared memory in computing systems) risks data inconsistency, known as race conditions (data races).

The industry has proposed three execution mechanisms to address race conditions in parallel execution: message passing, shared memory, and strict state access list mechanisms.

2.3 Message Passing Mechanism

Scenario 5: Assume a bank has four counters serving customers simultaneously. Give each teller a private ledger—only they can modify it—recording balances of their assigned customers.

When serving a customer, if the customer's info exists on their ledger, the teller proceeds directly; otherwise, they shout out the request to other tellers, who then handle it.

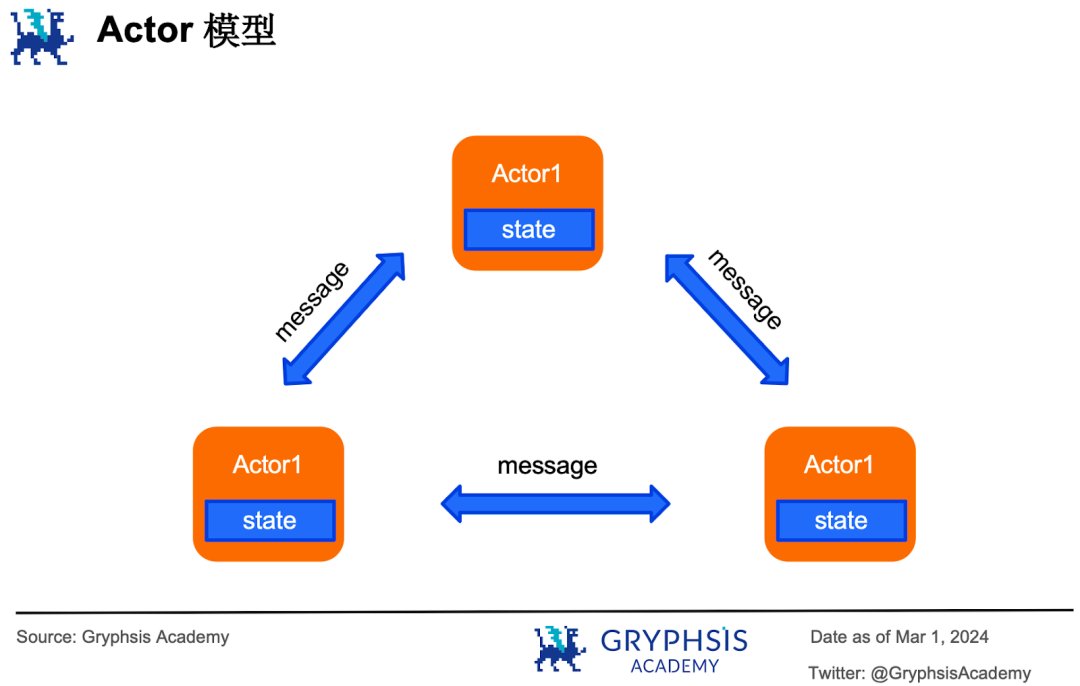

This is the principle behind the message-passing model. The Actor model is one such message-passing approach—each transaction executor is an actor (teller), possessing private data (private ledger). To access others' private data, they must send messages.

The advantage of the Actor model is that each actor accesses only its private data, thus avoiding race conditions entirely.

Its disadvantages are two-fold: First, each actor can only execute sequentially—in some cases failing to leverage parallel advantages (e.g., if Tellers 2, 3, and 4 simultaneously ask Teller 1 for Customer A's balance, Teller 1 must process each request one-by-one, though they could theoretically be handled in parallel). Second, there is no global view of system state—making it hard to grasp the full picture, debug, or fix bugs in complex systems.

2.4 Shared Memory Mechanism

2.4.1 Memory Lock Model

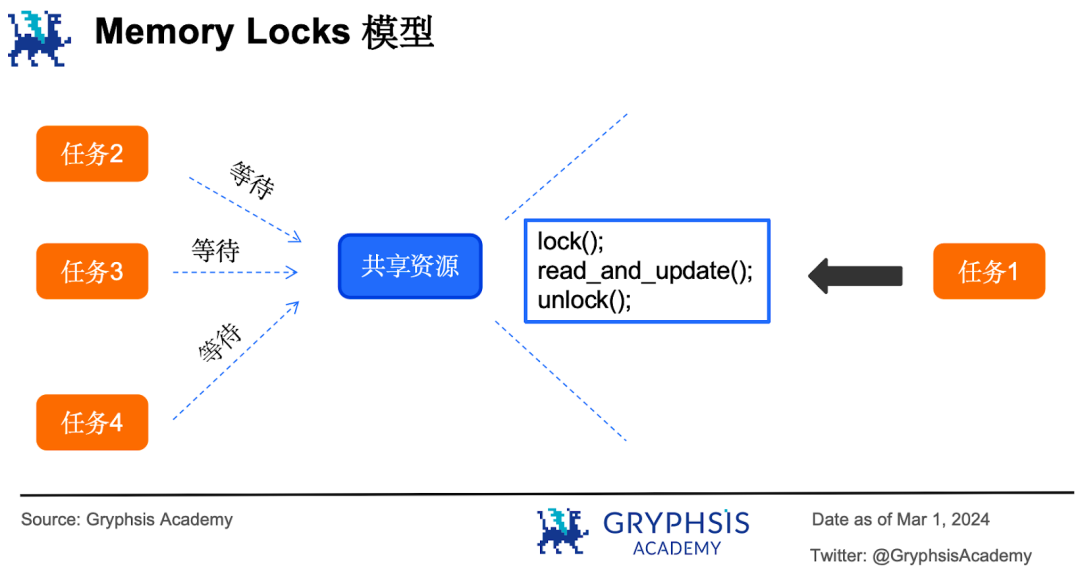

Scenario 6: Suppose the bank maintains a single master ledger recording all customer balances, with only one pen available to modify it.

In this case, the four tellers compete to serve customers: whichever teller grabs the pen (acquires the lock) first starts modifying the ledger, while the other three must wait. Once finished, they release the pen (unlock), allowing others to compete again—this is the memory lock model (memory locks).

Memory locks require parallel tasks to perform a "lock" operation when accessing shared resources. Only after locking can they access the resource, forcing other tasks to wait until the lock is released (unlocked) before attempting to acquire it.

Read-write locks (read-write lock) offer finer control—they allow either a read lock (read lock) or a write lock (write lock). Multiple tasks can hold read locks simultaneously to read data—but no modifications allowed. Write locks are exclusive—one at a time—and grant sole access to the holder.

Solana, Sui, and Sei v1 adopt the shared memory model based on memory locks. Though seemingly simple, implementation is complex and demands deep mastery of multithreaded programming. Small mistakes easily introduce various bugs:

-

Case 1: A task locks a shared resource but crashes during execution, leaving the resource permanently locked and inaccessible;

-

Case 2: A task acquires a lock but due to nested logic attempts to re-lock, leading to self-deadlock.

The memory lock model is prone to deadlocks, livelocks, and starvation:

(1) Multiple parallel tasks competing for multiple shared resources, each holding part of them and waiting for others to release—results in deadlock;

(2) A task detects another active task and voluntarily yields its held resource, leading to endless yielding back and forth—livelock;

(3) High-priority tasks always obtain resource access, while low-priority ones wait indefinitely—starvation.

2.4.2 Optimistic Parallelization

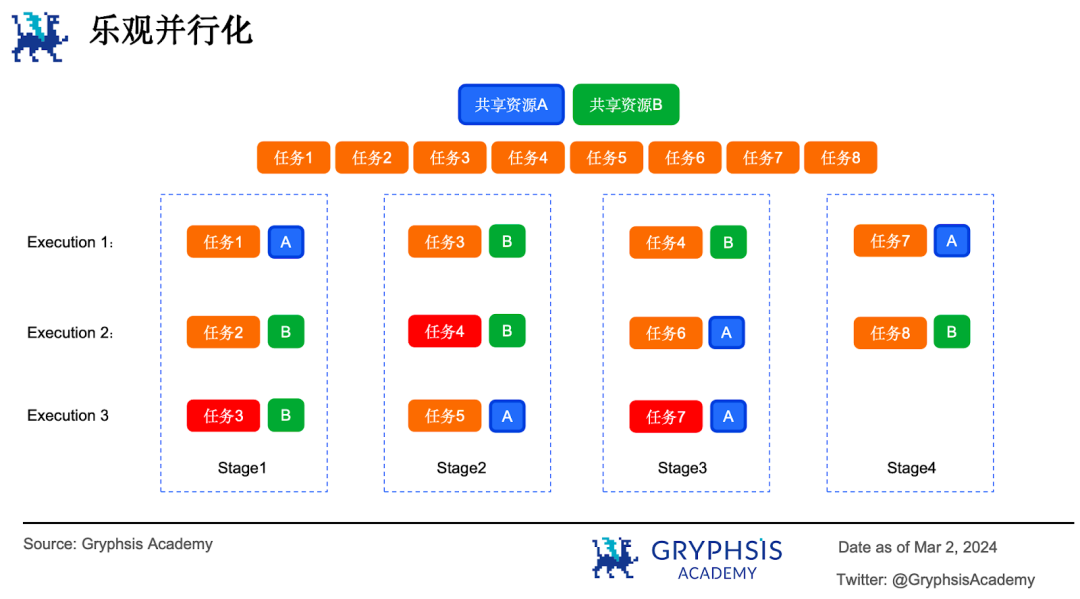

Scenario 7: Each of the four bank tellers independently reads and modifies the ledger regardless of others' usage. When using the ledger, they attach a personal tag to modified entries. After completing a transaction, they review it—if any entry bears someone else's tag, the transaction is invalidated and must be redone.

This is the core idea of optimistic parallelization. Its central principle is assuming all tasks are independent. Tasks are executed in parallel first, then validated afterward. If validation fails, the task is re-executed until all complete successfully. Suppose eight parallel tasks execute optimistically, accessing two shared resources A and B.

In Phase 1, Tasks 1, 2, and 3 execute in parallel. But Tasks 2 and 3 conflict on Resource B—so Task 3 is rescheduled. In Phase 2, Tasks 3 and 4 both access Resource B—Task 4 is rescheduled. This continues until all tasks finish. Notice how conflicting tasks repeatedly retry execution.

The optimistic parallelization model uses a multi-version in-memory data structure to record every written value along with its version (similar to tellers tagging entries).

Each parallel task runs in two phases: execution and validation. During execution, all read and write operations are recorded into a read set and write set. During validation, these sets are compared against the multi-version data structure—if not the latest version, validation fails.

Optimistic parallelization originates from Software Transactional Memory (STM), a lock-free programming mechanism in database systems. Because blockchain transactions naturally follow a deterministic order, this concept evolved into Block-STM. Aptos and Monad adopted Block-STM as their parallel execution mechanism.

Notably, Sei will abandon its original memory lock model in the upcoming v2 release, switching to optimistic parallelization. Block-STM achieves extreme speed—Aptos reached an astonishing 160k tps in experiments, 18x faster than sequential execution.

Block-STM handles complex execution and validation internally, allowing developers to write smart contracts as easily as sequential programs.

2.5 Strict State Access List

Message passing and shared memory mechanisms are based on the account/balance data model, which records each on-chain account's balance. Like a bank ledger showing Customer A has $1000, Customer B has $600—each transaction simply updates the balance state.

Alternatively, we could record only transaction details each time, forming a transaction log, from which account balances can be calculated. For example:

-

Customer A opens an account and deposits $1000;

-

Customer B opens an account ($0);

-

Customer A transfers $100 to Customer B.

By reading and calculating this log, we determine Customer A now has $900 and Customer B has $100.

UTXO (Unspent Transaction Output) resembles this transaction log data model—it's how Bitcoin, the first-generation blockchain, represents digital currency. Each transaction has inputs (how funds were obtained) and outputs (how they're spent), with UTXOs being unspent received amounts.

For instance, Customer A has 6 BTC and sends 5.2 BTC to Customer B, keeping 0.8 BTC. From a UTXO perspective: A's six 1-BTC UTXOs are destroyed; B receives one newly generated 5.2-BTC UTXO; A receives one newly generated 0.8-BTC UTXO as change. Six UTXOs destroyed, two new ones created.

Transaction inputs and outputs form a chain, with digital signatures tracking ownership—this forms the UTXO model. Blockchains using this model must sum all UTXOs of an address to determine current balance. Strict state access list implements parallel execution based on the UTXO model. It pre-computes each transaction's accessed addresses, forming an access list.

The access list serves two purposes:

(1) Ensuring transaction safety: If a transaction accesses an address not in the list, execution fails.

(2) Enabling parallel execution: Transactions are grouped into multiple sets based on access lists. Sets with no overlapping addresses (no dependencies) can be executed in parallel.

3. Industry Growth Drivers

From an intrinsic perspective, all things evolve from "nonexistence to existence" then "existence to excellence." Humanity's pursuit of greater speed is eternal. Numerous on-chain and off-chain solutions emerged to tackle blockchain execution speed. Off-chain solutions like rollups have gained substantial recognition, whereas the parallel EVM narrative still holds vast exploration potential.

Historically, with SEC approval of spot Bitcoin ETFs, the upcoming Bitcoin halving, and potential Fed rate cuts, crypto markets anticipate a bull run. Industry growth demands higher-throughput blockchain infrastructure as a solid foundation.

From a resource management standpoint, traditional blockchains process transactions sequentially—a simple method but wasteful of processor resources. Parallel blockchains maximize compute resource utilization, fully "extracting" multi-core processor performance and boosting overall network efficiency.

From an industry development perspective, despite continuous innovation in technology and business models, Web3's growth potential remains untapped. Centralized networks can push over 50,000 messages per second, send 3.4 million emails, perform 100,000 Google searches, and support thousands of players online simultaneously—decentralized networks cannot yet match this. To compete equally with centralized systems and claim their share, optimizing parallel execution and increasing transaction throughput is an inevitable path forward.

From a dApp development perspective, attracting more users requires superior user experience. Performance optimization is one key direction. DeFi users demand high-speed, low-cost transactions. GameFi users require real-time interactions. Both rely on parallel execution for support.

4. Challenges

Decentralization, security, and scalability—blockchain can satisfy only two of the three, known as the blockchain trilemma. Since decentralization is non-negotiable, enhancing scalability inherently compromises security. Code is written by humans, and humans make mistakes. The technical complexity introduced by parallel computing provides fertile ground for security vulnerabilities.

Multithreaded programming is prone to two main issues: first, improper concurrency control leads to race conditions; second, accessing invalid memory addresses causes crashes or exploitable buffer overflow vulnerabilities.

Project security can be evaluated from at least three angles. First, team background. Teams with systems programming experience possess deep knowledge of multithreading, capable of handling 80% of complex issues. Systems programming typically involves:

-

Operating systems

-

Device drivers

-

File systems

-

Databases

-

Embedded devices

-

Cryptography

-

Multimedia codecs

-

Memory management

-

Networking

-

Virtualization

-

Gaming

-

High-level programming languages

Second, code maintainability. Writing maintainable code follows established practices: clear architecture, proper use of design patterns for reusability, test-driven development with extensive unit tests, and refactoring to eliminate duplication.

Third, programming language choice. Some modern languages emphasize memory-safe concurrency by design. Compilers detect concurrency issues or potential invalid memory accesses and fail compilation, forcing developers to write robust code.

Rust stands out in this regard—which explains why most parallel blockchain projects are built with Rust. Some projects even borrow Rust's design to create their own smart contract languages, such as Fuel's Sway language.

5. Project Analysis

5.1 Based on Optimistic Parallelization

5.1.1 Transitioning from Memory Locks to Optimistic Parallelization: Sei v2

Sei is a general-purpose public chain based on open-source technology, founded in 2022. Its two co-founders are from UC Berkeley, and other team members also have elite international academic backgrounds.

Sei has raised three funding rounds: $5 million seed round, $30 million Series A, and undisclosed Series B. Additionally, Sei Network raised a $100 million fund to support ecosystem development.

In August 2023, Sei launched its mainnet, claiming to be the fastest L1 with 12,500 TPS and finality in just 380ms. Its current circulating market cap is nearly $2.2 billion.

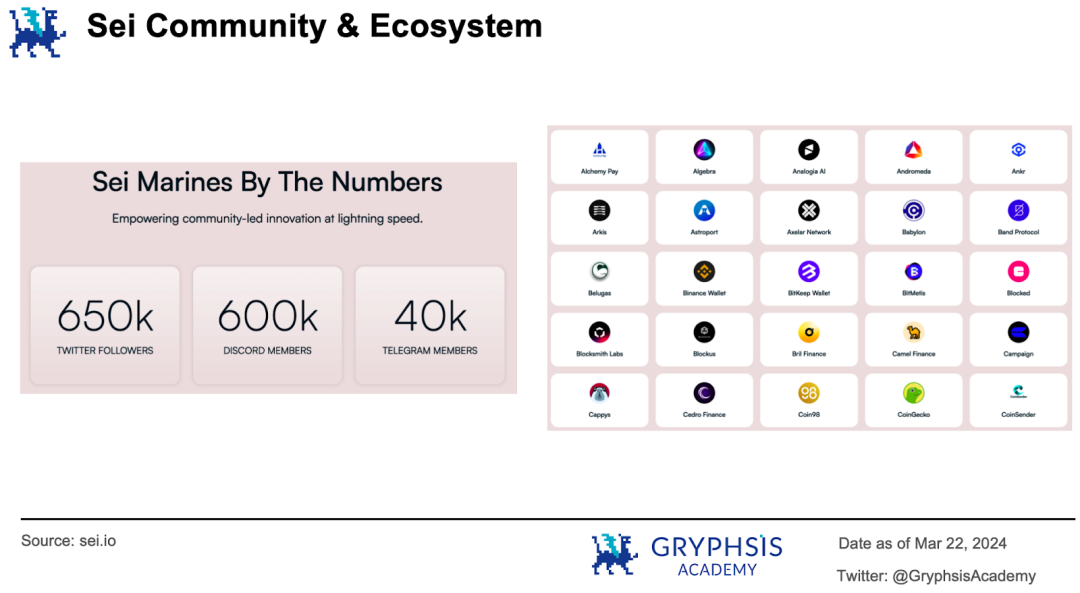

Sei currently hosts 118 ecosystem projects, primarily in DeFi, infrastructure, NFTs, gaming, and wallets. The community has 650K, 600K, and 40K members on Twitter, Discord, and Telegram respectively.

In late November 2023, Sei announced on its official blog the largest upgrade since mainnet launch—Sei v2—scheduled for H1 2024. Sei v2 claims to be the first parallel EVM blockchain, introducing the following new features:

-

Backward compatibility with EVM smart contracts: Developers can migrate EVM contracts without code changes

-

Reuse of common tools/applications like MetaMask

-

Optimistic parallelization: Sei v2 will abandon the shared memory access mechanism based on memory locks and adopt optimistic parallelization

-

SeiDB: Optimization of the storage layer

-

Support seamless interoperability between Ethereum and other chains

Sei previously implemented parallel transaction execution using a memory lock model. Before execution, all pending transactions' dependencies were parsed and a DAG generated, then transaction execution order was precisely orchestrated based on the DAG. This increased cognitive load on developers, who had to encode logic into contracts during development.

As explained earlier, with optimistic parallelization in the new version, developers can write smart contracts just like sequential programs. Complex mechanisms such as scheduling, execution, and validation are all handled by底层 modules. The core team's optimization proposal also introduces a design to further enhance parallel execution by pre-filling dependency relationships.

Specifically, it introduces a dynamic dependency generator that analyzes transaction write operations beforehand and pre-fills them into the multi-version in-memory data structure, optimizing potential data contention. The core team concluded that while this optimization may not benefit best-case transaction processing, it significantly improves worst-case execution efficiency.

5.1.2 Potential L1 Disruptor: Monad

If you missed the rise of previous public chains, don't miss Monad—it's hailed as a potential disruptor in the L1 space.

Founded in 2022 by two senior engineers from Jump Crypto, Monad completed a $19 million seed round in February 2023. In March 2024, Paradigm entered negotiations to lead a funding round exceeding $200 million—if successful, this would be the largest crypto financing since the beginning of the year.

The project has already achieved the milestone of launching its internal testnet and is working toward opening a public testnet.

Monad attracts strong investor interest for two standout reasons: strong technical credentials and effective marketing hype. The Monad Labs core team has 30 members with decades of experience in high-frequency trading, kernel drivers, and fintech, and rich expertise in distributed systems.

The project's daily operations are highly "down-to-earth": consistently engaging its 200K Twitter followers and 150K Discord members through "meme marketing"—such as weekly meme contests soliciting bizarre purple animal stickers or videos, spreading "viral culture" throughout the community.

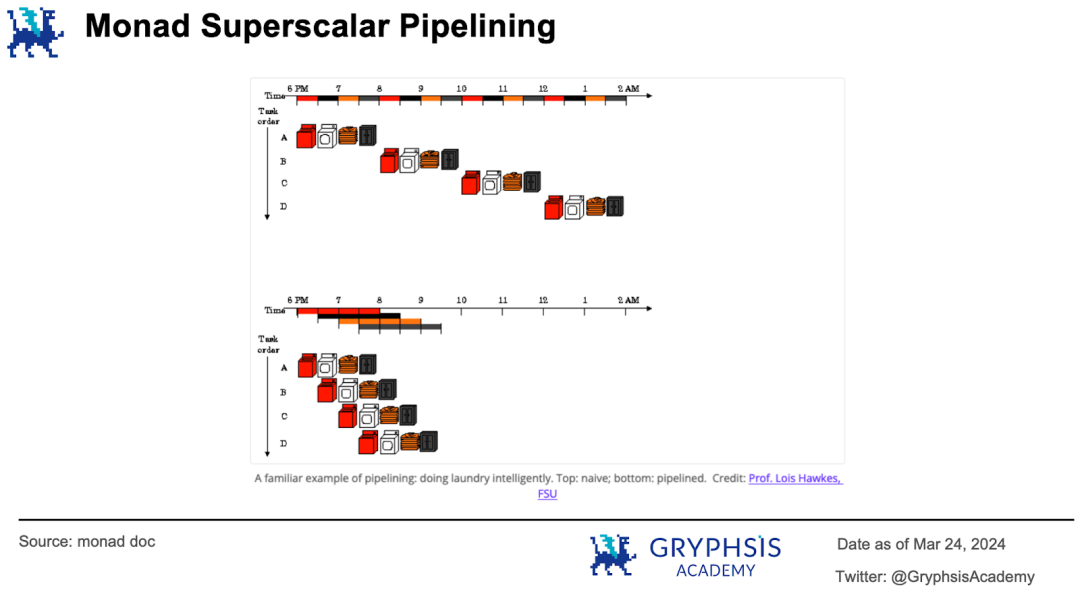

Monad's vision is to become a developer-focused smart contract platform, bringing extreme performance enhancements to the Ethereum ecosystem. Monad introduces two mechanisms to the Ethereum Virtual Machine: superscalar pipelining and an enhanced optimistic parallelization mechanism.

Superscalar pipelining parallelizes the transaction execution phase. The official documentation gives a vivid analogy: doing laundry resembles blockchain transaction processing, requiring multiple stages. The traditional way is to wash, dry, fold, and store one load completely before starting the next.

With superscalar pipelining, while the first load is drying, the second begins washing; while the first folds, the second dries and the third washes—ensuring no stage sits idle.

Optimistic parallelization enables parallel transaction execution. Monad uses optimistic parallelization for parallel execution. It also built its own static code analyzer to predict transaction dependencies, scheduling subsequent transactions only after prerequisite ones finish—greatly reducing repeated executions due to validation failures.

Current performance reaches 10,000 TPS with 1-second block times. As the project progresses, the core team will continue exploring further optimizations.

5.1.3 Highly Decentralized L1 Project: Canto

Founded in 2022 with no official foundation, no presale, no affiliation with any organization, and no fundraising—entirely community-driven, with even the core team anonymous and operating in a loose, decentralized manner. This is Canto, a highly decentralized L1 project built on Cosmos SDK.

Though an EVM-compatible general blockchain, Canto's primary vision is to become an accessible, transparent, decentralized, and free DeFi value platform. Long-term research reveals that any healthy DeFi ecosystem contains three foundational elements:

-

Decentralized exchanges (DEX) like Uniswap and Sushiswap;

-

Lending platforms like Compound and Aave;

-

Decentralized stablecoins like DAI, USDC, or USDT.

Yet past DeFi ecosystems eventually converged on the same fate: issuing governance tokens whose value depends on how much fee revenue they extract from future users—the more extracted, the higher the value. This resembles each DeFi protocol acting as a pay-per-hour private parking lot—the more users, the higher the valuation.

Canto takes a different approach: building free public infrastructure (Free Public Infrastructure) for DeFi, transforming itself into a free parking lot available for ecosystem projects to use at no cost.

The infrastructure includes three protocols: Canto DEX (a decentralized exchange), Canto Lending Market (CLM)—a pooled lending platform forked from Compound v2—and NOTE, a stablecoin minted by collateralizing assets in CLM.

Canto DEX operates perpetually as an immutable, governance-free protocol—neither issuing tokens nor charging extra fees—preventing rent-seeking behaviors among DeFi apps that lead to zero-sum games.

Governance of the CLM lending platform is controlled by stakers, who fully benefit from ecosystem growth, creating optimal conditions for developers and users, incentivizing continuous investment. Interest paid by borrowers borrowing NOTE goes entirely to lenders—protocol takes nothing.

For developers, Canto introduced the Contract Secured Revenue (CSR) model, allowing a portion of fees generated from user interactions with contracts to be allocated to developers. Canto's series of business innovations achieve a "triple win": creating constructive ecological prosperity through open, free financial infrastructure.

By sharing benefits widely with developers and users, it incentivizes participation and ecosystem enrichment. By retaining "minting rights" internally, it enables cross-application liquidity—making the token more valuable as the ecosystem grows. On January 26, 2024 (ET), when the CSR proposal passed community voting, its token $CANTO experienced a price surge.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News