"Four Questions" to Help You Understand How to Build an AVS

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

"Four Questions" to Help You Understand How to Build an AVS

An Active Validation Service (AVS) refers to any system that requires its own distributed validation semantics for verification.

By IOSG Ventures

Source: EigenLayer, IOSG

Recently, building infrastructure projects using EigenLayer has become highly popular within the developer community. These projects are known as Active Validated Services (AVS), referring to any system that requires its own distributed validation semantics for verification. Such systems can include DA layers, new VMs, oracles, bridges, and more.

But how exactly do you build an AVS?

To establish the fundamental rules of an AVS, you need to answer four key questions.

Q1: What defines a Task in your AVS?

In EigenLayer, a task is the smallest unit of work an Operator commits to perform for an AVS. These tasks may be associated with one or more slashing conditions of the AVS.

Here are two example tasks:

-

Hosting and serving a "DataStore" in EigenDA

-

Publishing the state root of another blockchain for a cross-chain bridge

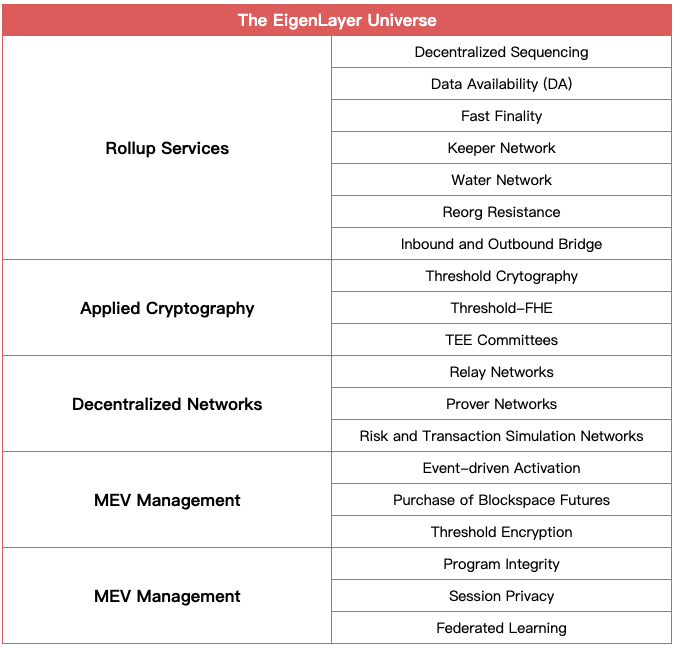

EigenLayer provides a more detailed example in the following workflow. The task of this AVS is to compute the square of a specific number.

-

A Task Generator publishes tasks at fixed time intervals. Each task specifies the number whose square needs to be computed. It also includes quorums and threshold percentages, requiring that each listed quorum must have a certain minimum percentage of Operators sign off on the task.

-

Operators currently enrolled in the AVS must read the task number from the task contract, compute its square, sign the result, and send both the result and signature to the Aggregator.

-

The Aggregator collects signatures from Operators and aggregates them. If responses from Operators meet or exceed the threshold percentage set by the Task Generator when publishing the task, the Aggregator combines these responses and submits them to the task contract.

-

During dispute resolution, anyone can raise a dispute. The DisputeResolution contract handles incorrect responses from a given Operator (or cases where the Operator fails to respond within the time window).

-

If a dispute is ultimately validated and processed, the Operator will be frozen in the Registration contract, subject to review by EigenLayer's veto committee regarding whether to uphold the freeze.

Q2: What kind of trust does your AVS want to inherit?

Source: EigenLayer, IOSG Ventures

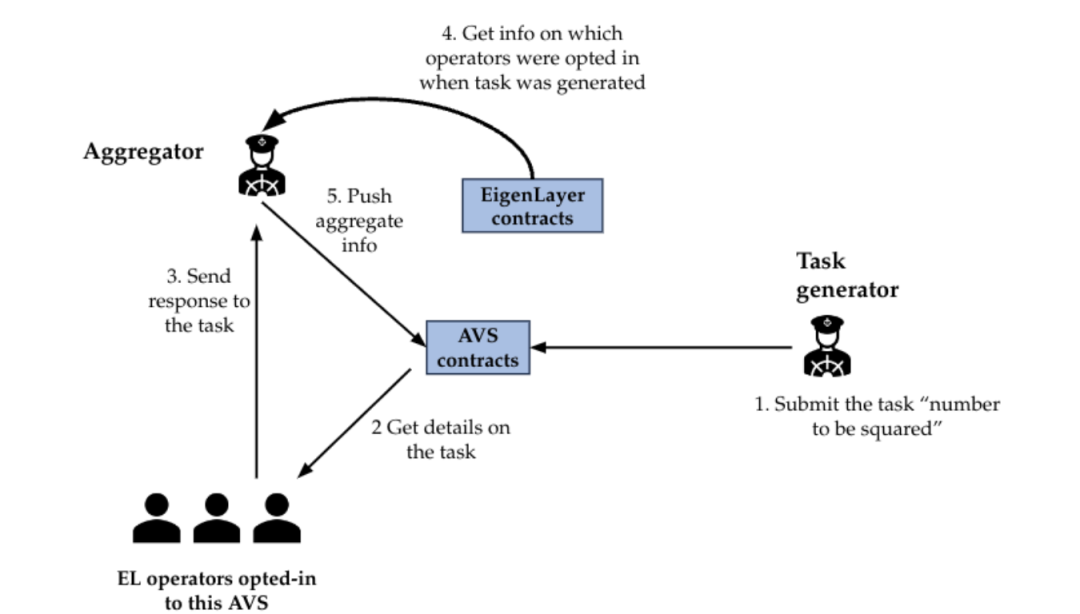

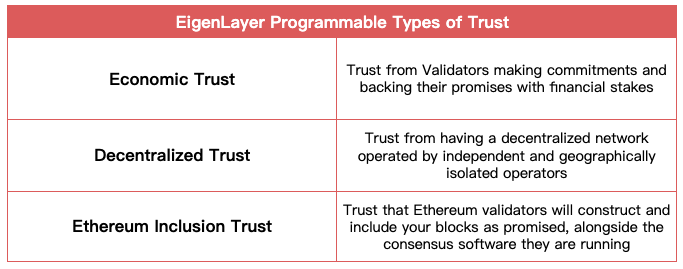

EigenLayer offers three types of programmable trust.

-

Economic Trust

Economic trust relies on confidence in staked assets. An economically rational actor will not launch an attack if the cost of corruption exceeds the potential profit. For instance, if attacking a cross-chain bridge costs $1 billion but yields only $500 million in profit, launching such an attack would be economically irrational.

As a widely adopted cryptoeconomic primitive, slashing can significantly increase the cost of corruption, thereby strengthening economic security.

-

Decentralized Trust

The essence of decentralized trust lies in having a large and widely distributed set of validators, both virtually and geographically. To prevent collusion among nodes and Liveness Attacks in an AVS, it’s best not to allow a single service provider to operate all nodes.

On EigenLayer, different AVSs can customize their level of decentralization. For example, they can impose geographic requirements on Operators or allow only individual Operators to run nodes, offering additional incentives accordingly to attract such participants.

Here is an example:

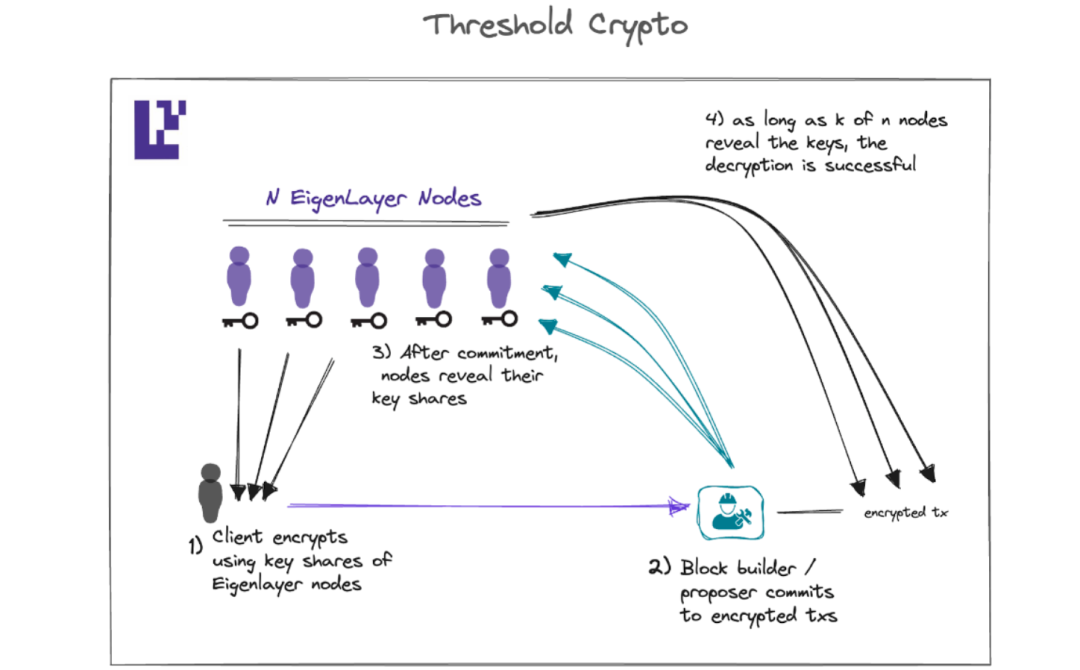

Shutter proposes a solution to prevent MEV using threshold encryption. This process involves a group of nodes called Keypers, who participate in computing a shared public and private key via Distributed Key Generation (DKG). These nodes are elected through governance by the Shutter DAO.

Clearly, DKG depends on the assumption of honest majority.

By leveraging node operation services provided by EigenLayer, Shutter can achieve broader distribution of Keypers. This approach not only reduces the risk of collusion among Keypers but also enhances network security and resilience.

Similarly, Lagrange’s Lagrange State Committee (LSC) consists of restakers. For each state proof, at least 2/3 of the committee members must sign a specific block header before a state proof is generated via SNARK.

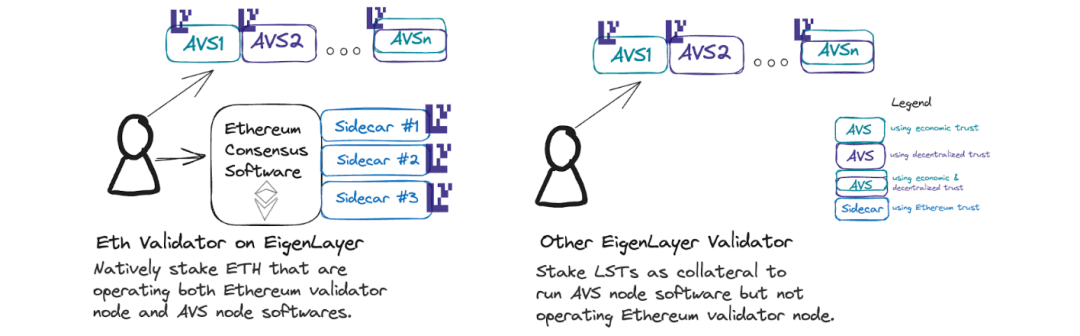

Ethereum Inclusion Trust

Ethereum validators, in addition to committing to Ethereum through staking, can make credible commitments to AVSs by restaking on EigenLayer. This enables proposers to offer certain services on Ethereum (e.g., partial block auctions via MEV-Boost++) without requiring changes at the Ethereum protocol layer.

For example, forward block space auctions allow buyers to pre-reserve future block space. Validators participating in restaking can make credible commitments to this block space; if they later fail to include the buyer’s transaction, they face slashing penalties.

Suppose you are building an oracle—you might need to provide pricing data over a certain period. Or suppose you are running an L2—you may need to publish L2 data to Ethereum every few minutes. These are use cases for forward block space auctions.

Q3: Is the work to be done by the operator lightweight or heavyweight?

If you wish to inherit the decentralization of Ethereum validators, the tasks of your AVS should be designed to be as lightweight as possible.

If tasks consume substantial computational resources, solo Operators may be unable to handle them.

Q4: What are the slashing conditions?

By restaking into a specific service, restakers accept the potential risk of being slashed, with the slashing conditions defined by the AVS.

As an AVS, you should design slashing conditions that are on-chain verifiable, provable, and objectively attributable. Examples include double-signing a block in Ethereum, or a light-node bridge AVS validator signing an invalid block from another chain.

Poorly designed slashing conditions could lead to disputes and systemic risks.

An AVS should also ensure observability, enabling cross-service monitoring, tracking, and logging of requests and responses.

How to quantify?

How much trust does your AVS require—measured in restaked capital, number of distinct distributed validators, and number of Ethereum validators making inclusion commitments—and how will you incentivize it?

For example, if a cross-chain bridge processes $100 million in weekly transaction volume and rents $100 million worth of security, users can trust they are protected. Even if validators attempt to compromise the system, users remain safeguarded because compensation can be redistributed through slashing mechanisms.

Given that parameters such as the bridge’s TVL, amount of restaked ETH, number of participating Operators, and others may fluctuate significantly over time, the AVS needs a mechanism to dynamically adjust its security budget and buffer.

An AVS can allocate a portion of its total token supply to pay for economic security.

But, do I compromise my token utility by using EigenLayer?

Absolutely not!

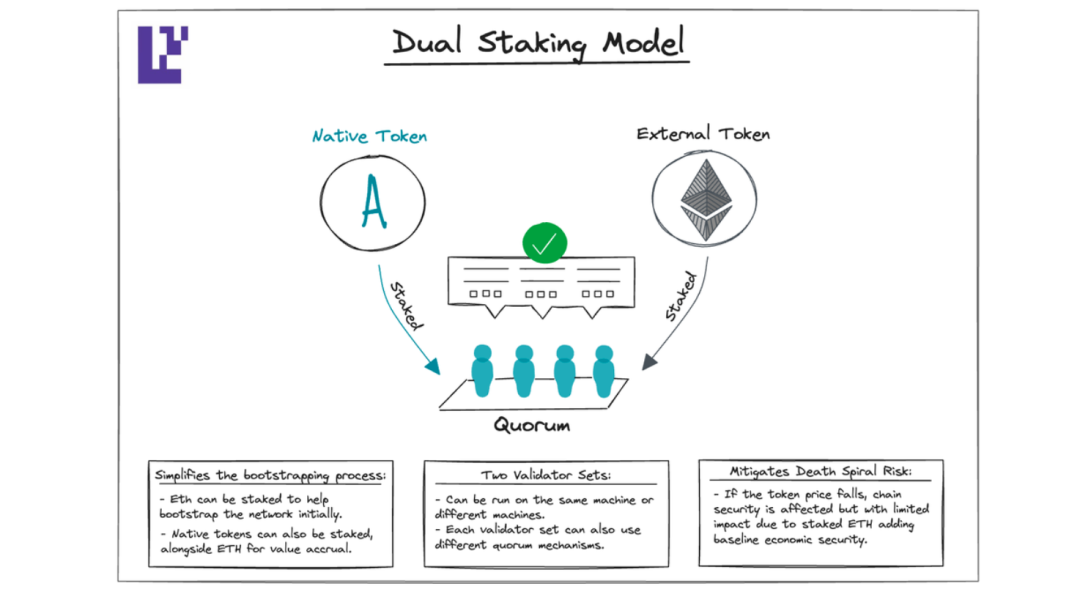

EigenLayer supports dual staking, allowing you to secure the network using both ETH and your native token simultaneously, adjusting the ratio of each as needed. In the early stages of the network, ETH may constitute a larger share. As the network matures, you may prefer your native token to play a more prominent role. In such cases, the AVS can increase the weight of the native token through protocol governance.

Moreover, when an AVS experiences rapid short-term growth in security demands—for instance, when the TVL of DeFi protocols served by an AVS oracle rapidly increases—the AVS can still leverage EigenLayer to reinforce its economic security.

From this perspective, EigenLayer functions as a programmable trust market, delivering "elastic" security.

What external tools can I use?

Below are some notable projects.

-

In EigenLayer’s three-party market, Operators rely on AVS developers to correctly code AVS software and set reasonable slashing conditions. However, given the diversity of AVSs, interaction logic between each AVS and Operators may vary, creating a new domain. To prevent unintended slashing events, AVSs can audit their codebase before deployment. Additionally, EigenLayer has a veto committee capable of rejecting improper slashing decisions via multi-sig approval.

-

Meanwhile, Cubist is collaborating with EigenLabs to develop an open anti-slashing framework that leverages secure hardware and employs custom policies within key managers to sign transactions and validate messages. For example, signing block headers at two different heights would never be approved by the policy engine inside the key manager.

-

Restakers/Operators with higher risk tolerance may wish to participate in early-stage AVSs for higher returns. In such cases, Cubist’s Anti-slasher could prove useful.

-

Many know that EigenLayer helps AVSs build trusted networks—but how much should an AVS pay for economic security, and how can it defend against economic attacks?

-

Anzen Protocol developed the Security Factor (SF), a universal metric for measuring the economic security of an AVS. SF is based on the concepts of cost of corruption and profit from corruption.

-

Anzen helps AVSs maintain a minimum level of economic security without overpaying for it.

-

EigenLabs is developing the EigenSDK to help AVSs write their node software. The SDK includes modules for signature aggregation, interaction logic with EigenLayer contracts, networking, cryptography, and event monitoring clients.

-

Meanwhile, Othentic is building a development toolkit to help AVSs launch products faster.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News