Kernel Ventures: A Deep Dive into DA and Historical Data Layer Design

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Kernel Ventures: A Deep Dive into DA and Historical Data Layer Design

As blockchain functionalities become increasingly complex, they bring greater demand for storage space.

Author: Kernel Ventures Jerry Luo

TL;DR

Early blockchains required all network nodes to maintain data consistency to ensure security and decentralization. However, as blockchain ecosystems grow, storage pressure increases significantly, leading to centralization trends in node operation. Current Layer1s urgently need to address the rising storage costs caused by increasing TPS.

To solve this issue, developers must propose new historical data storage solutions while balancing security, storage cost, data retrieval speed, and DA layer universality.

In addressing this challenge, many new technologies and approaches have emerged, including Sharding, DAS (Data Availability Sampling), Verkle Tree, and DA middleware components. These aim to optimize DA layer storage by reducing data redundancy and improving data verification efficiency.

Current DA solutions can be broadly categorized into two types based on data storage location: on-chain DA and third-party DA. On-chain DA reduces node storage burden through periodic data cleanup or sharded storage. Third-party DA solutions are specifically designed for storage services and offer robust handling of large data volumes, primarily making trade-offs between single-chain and multi-chain compatibility, resulting in three models: chain-specific DA, modular DA, and storage blockchain DA.

Payment-focused blockchains with high demands for historical data security are best suited for using their mainchain as the DA layer. For long-running chains with extensive miner participation, adopting a third-party DA solution that avoids consensus-layer changes while maintaining security may be more appropriate. General-purpose blockchains benefit more from chain-specific DA solutions offering larger capacity, lower cost, and strong security. However, considering cross-chain needs, modular DA is also a viable option.

Overall, blockchains are evolving toward reduced data redundancy and increased specialization across multiple chains.

1. Background

As distributed ledgers, blockchains require every node to store a copy of historical data to ensure data security and sufficient decentralization. Since the validity of each state change depends on the previous state (transaction source), a blockchain should theoretically retain all transaction records from genesis to present. Taking Ethereum as an example, even at an average block size of 20 KB, the total blockchain size has reached approximately 370 GB. A full node stores not only blocks but also state and transaction receipt data—bringing total storage per node beyond 1 TB, which concentrates node operation among fewer participants.

Latest Ethereum block height, image source: Etherscan

2. DA Performance Metrics

2.1 Security

Compared to databases or linked lists, blockchains achieve immutability by allowing new data to be cryptographically verified against historical data. Therefore, ensuring the security of historical data is paramount in DA layer design. Blockchain data security is typically evaluated based on data redundancy quantity and data availability verification methods.

Redundancy Quantity: Data redundancy in blockchain systems serves several purposes. First, higher redundancy allows validators seeking to verify past account states to access more reference samples, enabling them to identify data recorded by the majority of nodes. In traditional databases, where data is stored in key-value pairs on individual nodes, altering history requires modifying only one node—making attacks extremely cheap. Theoretically, greater redundancy leads to higher data credibility. Additionally, more storage nodes reduce the risk of data loss. This contrasts sharply with centralized Web2 game servers, which shut down completely if backend servers go offline. However, redundancy isn't always better—each copy consumes additional storage space, so excessive redundancy creates undue system burden. An optimal DA layer balances security and storage efficiency through intelligent redundancy strategies.

Data Availability Verification: While redundancy ensures widespread data recording, actual usage requires verifying accuracy and completeness. Modern blockchains use cryptographic commitment schemes—storing compact commitments derived from transaction data. To verify a historical record, one reconstructs the commitment and checks it against the globally stored value. If they match, verification passes. Common cryptographic verification algorithms include Merkle Root and Verkle Root. High-security verification schemes minimize required verification data and enable fast historical data checks.

2.2 Storage Cost

After establishing baseline security, the next core goal for the DA layer is cost reduction and efficiency improvement—specifically lowering the memory footprint per unit of stored data (assuming uniform hardware performance). Current approaches mainly involve sharding techniques and incentivized storage to maintain effective data preservation while reducing backup counts. However, these improvements reveal a trade-off between storage cost and data security—lowering storage overhead often compromises security. Thus, an ideal DA layer achieves balance between cost and security. Additionally, when the DA layer itself is a standalone blockchain, minimizing intermediate steps during data exchange helps reduce costs. Each transfer step generates indexing data for future queries, so longer call chains increase storage costs. Finally, data persistence directly correlates with storage cost—higher costs make long-term data retention harder for public chains.

2.3 Data Retrieval Speed

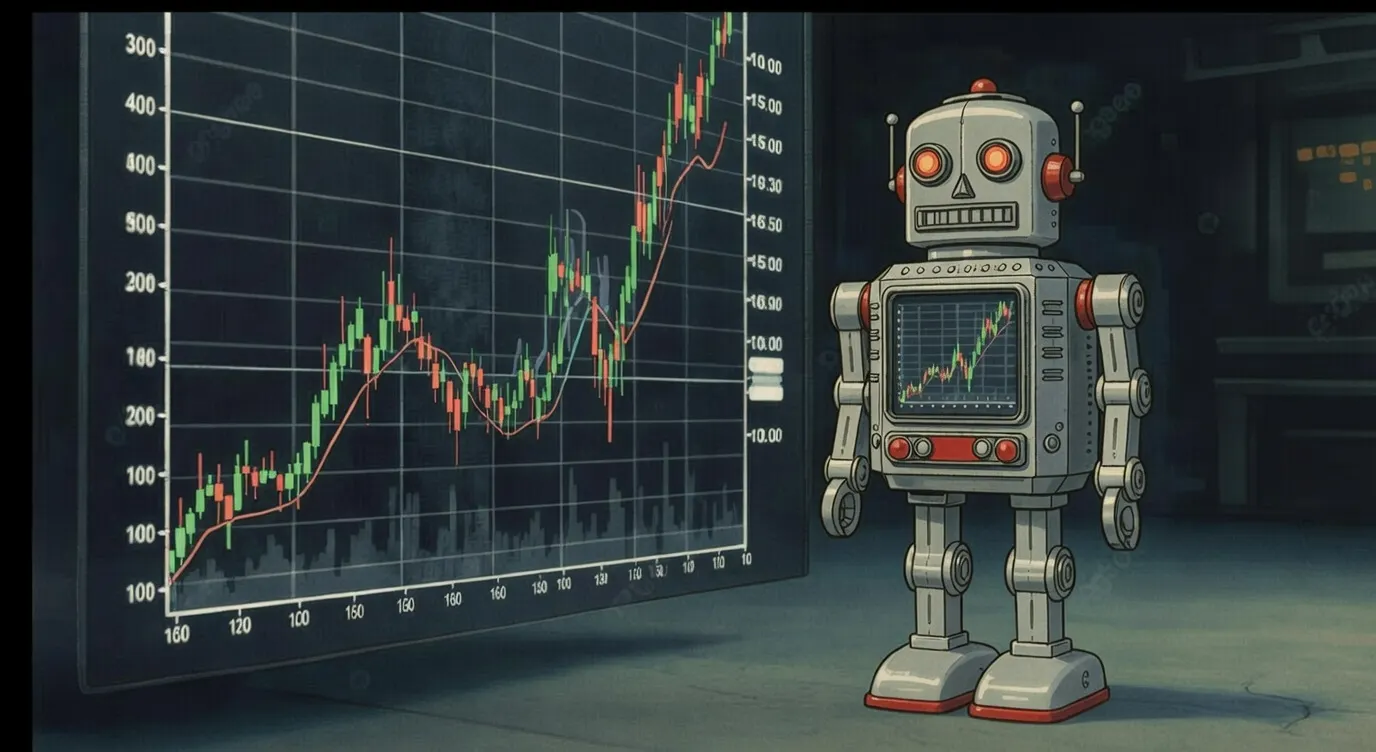

After cost reduction comes efficiency—specifically the ability to quickly retrieve data from the DA layer when needed. This involves two steps: first, locating the node storing the data—only relevant for chains without full network-wide data consistency. Chains achieving global synchronization can skip this latency. Second, most mainstream blockchain systems—including Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Filecoin—use LevelDB for node storage. In LevelDB, data is stored in three ways: newly written data goes into Memtable files; once full, Memtables become Immutable Memtables. Both reside in RAM, though Immutable Memtables allow only reads. IPFS uses hot storage here—enabling fast memory access—but typical mobile device RAM is GB-scale and fills quickly. Moreover, memory-resident data is permanently lost upon node crashes. For persistent storage, data must be written to SSDs in SST files, requiring loading into memory before access—greatly slowing lookup speeds. Furthermore, in sharded systems, data reconstruction requires requesting fragments from multiple nodes—a process that further slows retrieval.

LevelDB data storage mechanism, image source: LevelDB Handbook

2.4 DA Layer Universality

With DeFi growth and recurring CEX issues, user demand for decentralized cross-chain asset trading continues to rise. Regardless of whether cross-chain mechanisms use hash locking, notaries, or relays, they inevitably require finality confirmation on both chains’ historical data. The crux lies in data isolation across different decentralized systems, preventing direct communication. A proposed solution rethinks DA layer architecture: storing multiple blockchains' historical data on a single trusted chain, allowing verification via simple data calls. This requires the DA layer to establish secure communication protocols with diverse blockchains—i.e., high universality.

3. Exploration of DA Technologies

3.1 Sharding

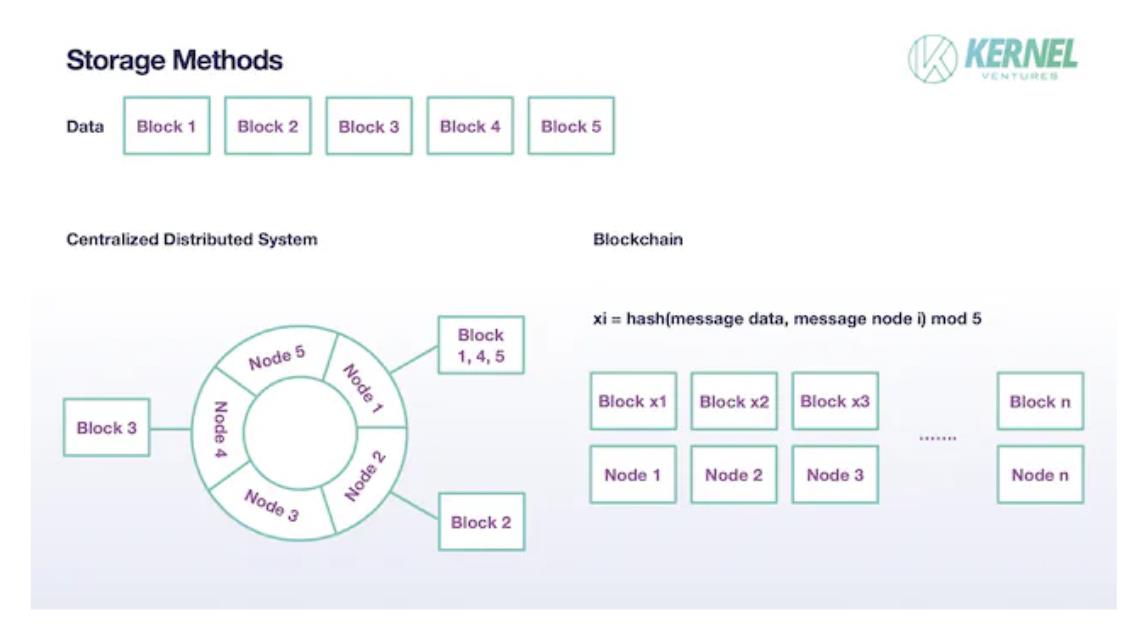

In traditional distributed systems, files aren’t stored whole on single nodes. Instead, original data is split into Blocks, with each node storing one Block. Blocks are usually backed up appropriately across other nodes—typically two copies in modern systems. This sharding approach reduces individual node storage load, scales total system capacity to the sum of individual node capacities, and maintains safety through moderate redundancy. Blockchain sharding follows similar principles, differing in specifics. First, since blockchain nodes are assumed untrusted, sufficiently large data backups are essential for validating authenticity later—requiring far more than two replicas. Ideally, in such a system with T total validator nodes and N shards, replica count should be T/N. Second, regarding Block assignment: traditional systems have few nodes, so one node often manages multiple data blocks. Consistent hashing maps data onto a ring, with each node responsible for a segment. Nodes may sometimes receive no storage tasks. On blockchains, however, every node *must* store a Block—it’s deterministic, not random. Each node randomly selects one Block via hashing combined block data and node info, then taking modulo N. Assuming data is divided into N Blocks, each node stores only 1/N of the original size. By tuning N appropriately, networks can balance rising TPS with manageable node storage pressure.

Sharded data storage model, image source: Kernel Ventures

3.2 DAS (Data Availability Sampling)

DAS builds upon sharding as a further storage optimization. With basic random sharding, there's a chance some Blocks could be lost entirely. Also critical is how to verify authenticity and completeness during data reconstruction. DAS addresses both problems using Erasure Coding and KZG polynomial commitments.

Erasure Code: Given Ethereum’s vast number of validators, the probability of any Block being unrecorded approaches zero—but remains theoretically possible. To mitigate this risk, instead of directly splitting raw data into Blocks, the scheme maps original data to coefficients of an n-degree polynomial, then samples 2n points along it. Nodes randomly select one point to store. An n-degree polynomial can be reconstructed from just n+1 points—so even if only half the Blocks are preserved, full recovery remains possible. Erasure coding thus enhances data safety and network resilience.

KZG Polynomial Commitment: Authenticating stored data is crucial. In networks without erasure coding, various verification methods exist. But once erasure coding is introduced for enhanced security, KZG polynomial commitment becomes particularly suitable. It enables direct content validation of individual Blocks in polynomial form—eliminating the need to revert polynomials back to binary data. The overall verification resembles Merkle Trees but doesn’t require specific Path node data—only the KZG Root and Block data are needed to confirm authenticity.

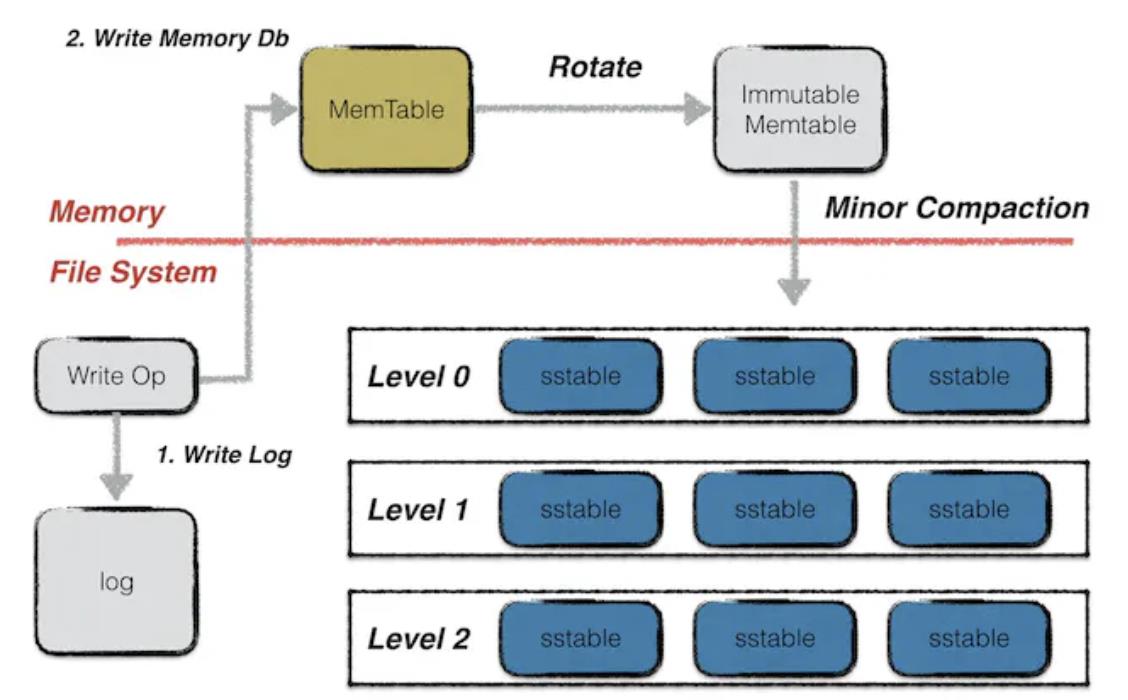

3.3 DA Layer Data Verification Methods

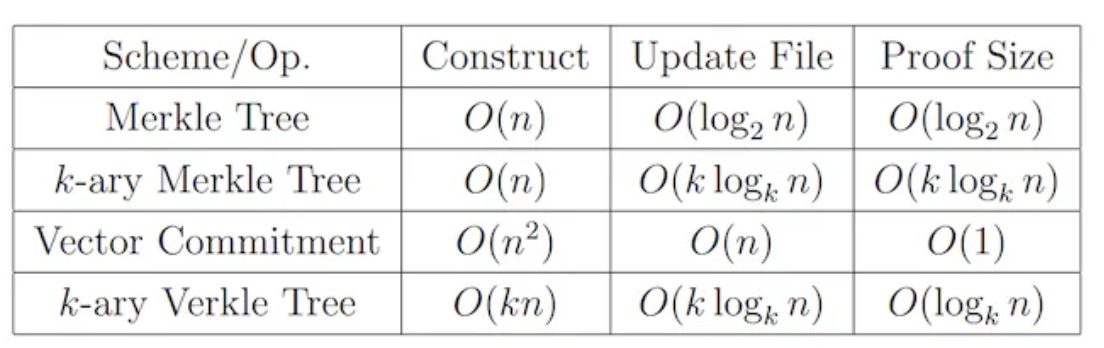

Data verification ensures retrieved data hasn’t been tampered with and isn’t incomplete. To minimize verification data volume and computational cost, DA layers currently favor tree structures. The simplest method uses Merkle Trees, employing perfect binary trees—requiring only a Merkle Root and sibling subtree hashes along the path for verification. Time complexity is O(logN) (log₂N by default). Though greatly simplified, verification data still grows with dataset size. To address growing verification overhead, Verkle Trees have been proposed. In Verkle Trees, each node stores not only its value but also a Vector Commitment. Using the original node value and this commitment proof, authenticity can be rapidly verified without fetching sibling nodes—making computation count dependent only on tree depth (a fixed constant), dramatically accelerating verification. However, generating Vector Commitments requires participation from all sibling nodes at the same level—significantly increasing write and update costs. But for immutable historical data meant for permanent storage—where reading dominates over writing—Verkle Trees are highly suitable. Both Merkle and Verkle Trees also have K-ary variants with similar mechanisms but varying child counts per node. Their performance comparison is shown below.

Comparison of data verification time performance, image source: Verkle Trees

3.4 Universal DA Middleware

As the blockchain ecosystem expands, so does the number of public chains. Due to distinct advantages and irreplaceability across domains, short-term unification of Layer1 chains seems unlikely. Yet with DeFi growth and persistent CEX shortcomings, demand for decentralized cross-chain asset trading keeps rising. Consequently, multi-chain data storage in the DA layer—eliminating cross-chain interaction risks—is gaining attention. To accept historical data from diverse chains, the DA layer must provide decentralized protocols for standardized data flow storage and verification. For instance, kvye—a middleware built on Arweave—actively pulls data from chains and standardizes its storage format on Arweave, minimizing transmission differences. In contrast, Layer2 solutions dedicated to specific chains share internal nodes for data exchange—reducing cost and boosting security—but suffer major limitations by serving only designated chains.

4. DA Layer Storage Solutions

4.1 On-Chain DA

4.1.1 DankSharding-like Approaches

This category lacks a formal name, with Ethereum’s DankSharding being the most prominent representative—hence “DankSharding-like” used here. These solutions leverage two key DA technologies: Sharding and DAS. First, data is split into appropriate chunks via sharding. Then, each node stores one chunk using DAS. With sufficiently many nodes, a large shard count N can be chosen—reducing each node’s storage load to 1/N of original, effectively expanding total storage capacity by N×. To prevent worst-case scenarios where no node stores a particular Block, DankSharding applies Erasure Coding—allowing full reconstruction from just 50% of data. Finally, data verification uses Verkle Trees and polynomial commitments for rapid validation.

4.1.2 Short-Term Storage

For on-chain DA, one of the simplest data handling methods is short-term storage. Fundamentally, blockchains serve as public ledgers—enabling collective witnessing and state updates—without inherent requirements for permanent storage. Solana exemplifies this: although its historical data syncs to Arweave, mainnet nodes keep only the last two days of transactions. Account-based chains only need to preserve the final state at any moment—sufficient to validate subsequent changes. Projects needing earlier data can store it independently on other decentralized chains or trusted third parties. Essentially, those requiring extended data retention must pay for storage themselves.

4.2 Third-Party DA

4.2.1 Chain-Specific DA: EthStorage

Chain-Specific DA: The most critical aspect of DA layers is data transmission security—highest when using the mainchain itself. However, on-chain storage faces space constraints and resource competition. When network data grows rapidly, third-party DA offers a better alternative for long-term storage. Third-party DAs gain significant advantages if they share nodes with the mainnet—enabling higher security during data exchange. Hence, under equal security assumptions, chain-specific DA holds major benefits. For Ethereum, a fundamental requirement is EVM compatibility—ensuring interoperability with Ethereum data and contracts. Notable projects include Topia and EthStorage. Among them, EthStorage currently offers the most comprehensive integration—not only supporting EVM-level compatibility but also providing dedicated interfaces connecting to Ethereum development tools like Remix and Hardhat, achieving toolchain-level alignment.

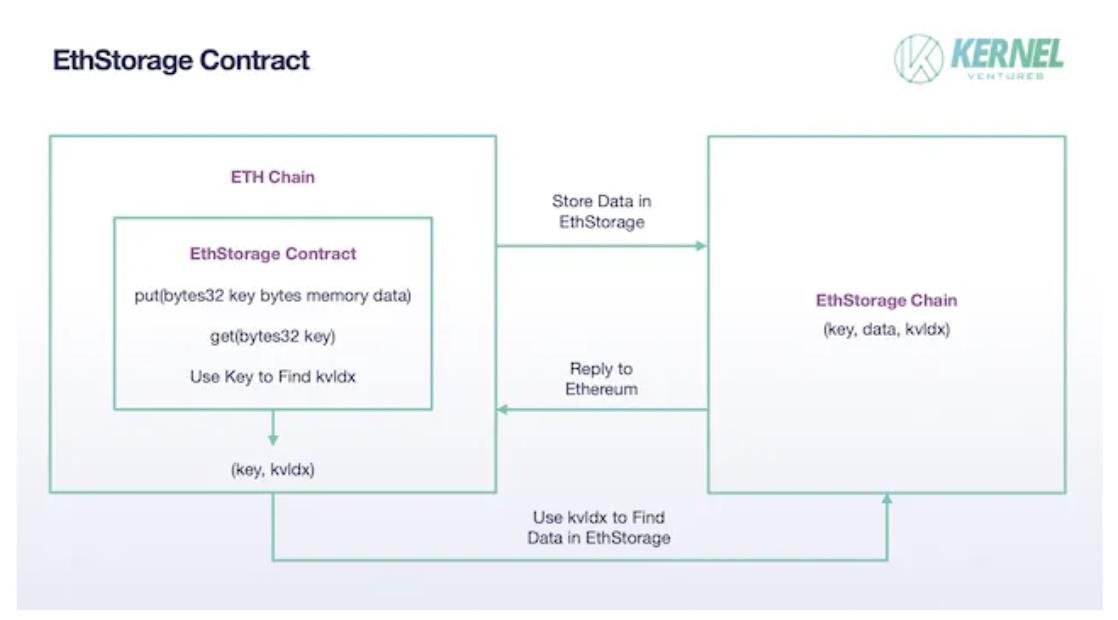

EthStorage: EthStorage is an independent blockchain whose nodes form a superset of Ethereum nodes—meaning EthStorage nodes can simultaneously run Ethereum clients. Ethereum opcodes can directly interact with EthStorage. In this model, only minimal metadata is retained on Ethereum for indexing—effectively creating a decentralized database for Ethereum. Currently, EthStorage enables interaction via a deployed contract on Ethereum. To store data, Ethereum calls the contract’s put() function with two byte parameters: key and data—where data is the payload and key serves as its identifier (similar to CID in IPFS). After successfully storing the (key, data) pair on the EthStorage network, EthStorage returns a kvldx value mapped to the key on Ethereum—representing the data’s storage address. This transforms potentially massive data storage into simply storing a small (key, kvldx) pair—drastically reducing Ethereum’s storage burden. To retrieve previously stored data, users call EthStorage’s get() function with the key parameter, using the stored kvldx to quickly locate the data within EthStorage.

EthStorage contract, image source: Kernel Ventures

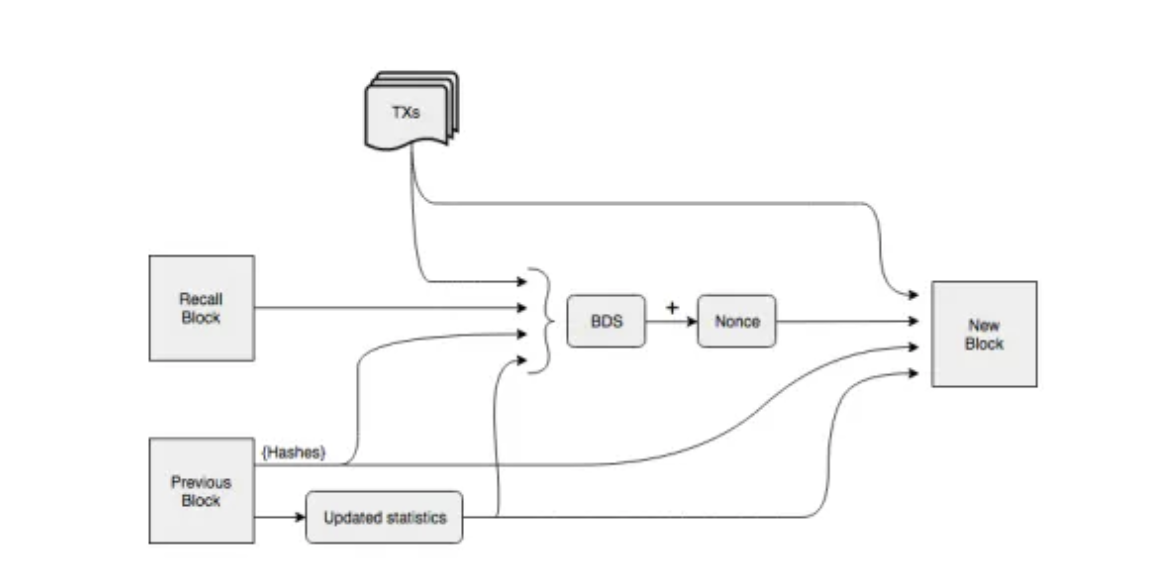

Regarding actual data storage, EthStorage adopts Arweave’s model. It first shards numerous (k,v) pairs from ETH—each shard containing a fixed number of (k,v) entries, with size limits per entry to ensure fair work measurement during miner reward distribution. Before rewarding storage, node compliance must be verified. EthStorage divides each shard (TB-scale) into many chunks and retains a Merkle root on Ethereum for validation. Miners must submit a nonce combining with the previous block’s hash to generate random chunk addresses. They must then provide those chunks’ data to prove full shard storage. However, the nonce cannot be arbitrary—otherwise nodes might pick favorable nonces matching only stored chunks. Thus, the generated chunks must collectively meet difficulty requirements after mixing and hashing—and only the first miner submitting a valid nonce and proof earns the reward.

4.2.2 Modular DA: Celestia

Blockchain Modules: Modern Layer1 blockchains perform four primary functions: (1) designing underlying network logic, selecting validators, writing blocks, and distributing rewards; (2) bundling and publishing transactions; (3) validating pending transactions and finalizing state; (4) storing and maintaining historical blockchain data. Based on functionality, blockchains can be divided into four modules: Consensus Layer, Execution Layer, Settlement Layer, and Data Availability Layer (DA Layer).

Modular Blockchain Design: Historically, all four modules were integrated into a single chain—known as monolithic blockchains. This design is stable and easy to maintain but imposes heavy burdens on individual chains. In practice, these modules compete for limited computing and storage resources. For example, improving execution speed increases DA layer storage pressure; enhancing security requires complex validation, slowing transaction processing. Developers face constant trade-offs. To overcome performance bottlenecks, modular blockchain architectures were proposed—separating one or more modules onto dedicated chains. This allows specialized chains to focus solely on speed or storage, overcoming limitations imposed by weakest-link effects.

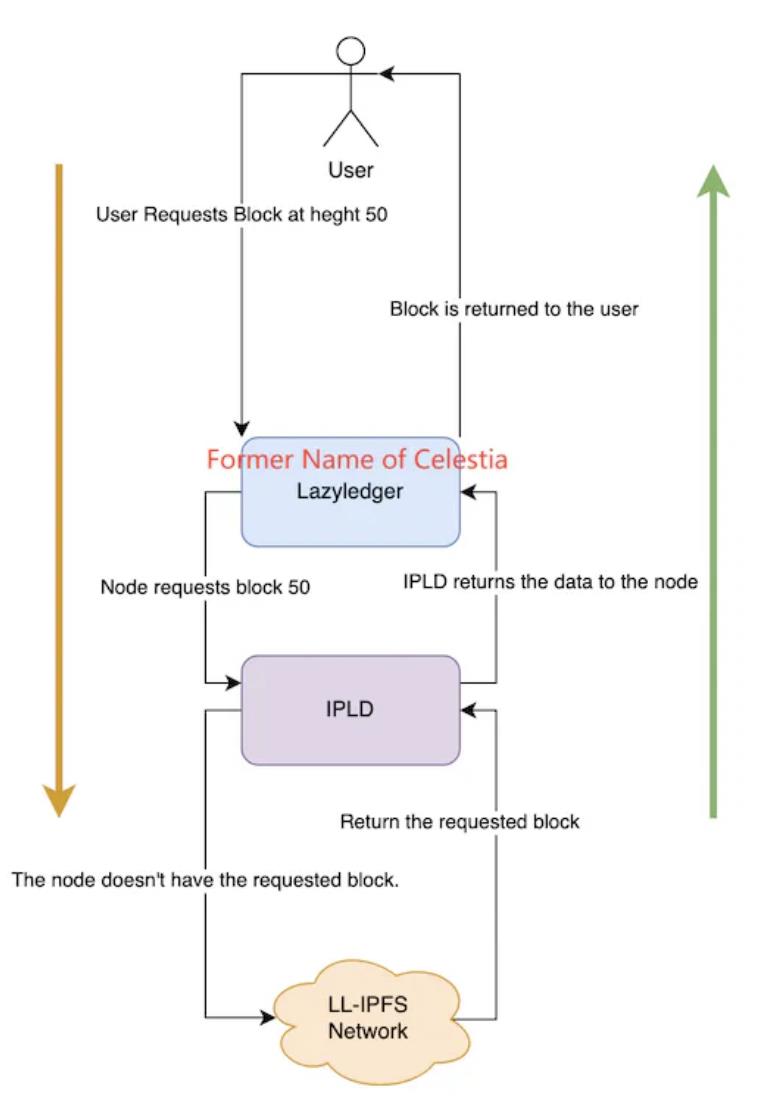

Modular DA: Offloading the DA layer to a separate chain is seen as a viable solution to growing Layer1 historical data. This area remains early-stage, with Celestia being the most representative project. Celestia adopts Danksharding-inspired storage—splitting data into Blocks, assigning partial storage to nodes, and using KZG polynomial commitments for integrity checks. It also employs advanced 2D Reed-Solomon erasure coding—rewriting original data into k×k matrices, enabling full recovery from just 25% of fragments. However, sharded storage merely scales node storage linearly with total data volume. As Layer1 improves transaction speed, node storage pressure may eventually reach unsustainable levels. To address this, Celestia introduces IPLD. Matrix data isn’t stored directly on Celestia but on LL-IPFS, with nodes retaining only the IPFS CID. When users request data, nodes query IPLD with the CID to fetch originals. If available, data returns via IPLD; otherwise, retrieval fails.

Celestia data retrieval mechanism, image source: Celestia Core

Celestia: Celestia illustrates how modular blockchains can tackle Ethereum’s storage challenges. Rollup nodes send batched and validated transaction data to Celestia for storage—where Celestia blindly accepts and stores it. Rollups pay tia tokens proportional to storage size. Celestia leverages DAS and erasure coding similar to EIP-4844—but upgrades polynomial erasure coding to 2D RS codes, enhancing security—requiring only 25% of fragments to reconstruct full transaction data. At its core, Celestia is simply a low-cost PoS chain. To fully resolve Ethereum’s historical data problem, additional modules must integrate with Celestia. For rollups, Sovereign Rollups are strongly recommended. Unlike common Layer2 rollups handling only execution, Sovereign Rollups manage full execution and settlement—minimizing Celestia’s involvement. Given Celestia’s security lags behind Ethereum’s, this maximizes end-to-end transaction security. For Ethereum-side data retrieval security, the dominant solution today is the Quantum Gravity Bridge smart contract. It maintains a Merkle Root (data availability proof) of Celestia-stored data on Ethereum. Whenever Ethereum retrieves data from Celestia, it compares the hash result with the Merkle Root—validating authenticity only upon match.

4.2.3 Storage Blockchain DA

On-chain DA borrows many sharding-like techniques from storage blockchains. Some third-party DAs even delegate partial storage tasks directly to storage chains—e.g., Celestia places actual transaction data on LL-IPFS. Beyond building dedicated chains to solve Layer1 storage, a more direct approach lets storage blockchains interface directly with Layer1, hosting its massive historical data. High-performance blockchains generate enormous data volumes—Solana, for example, reaches nearly 4 petabytes at full speed—far exceeding ordinary node capabilities. Solana’s solution: store history on Arweave, keeping only two days’ data on mainnet nodes for validation. To secure this process, Solana and Arweave co-developed Solar Bridge—a dedicated storage bridge protocol. Verified Solana data syncs to Arweave and returns a tag. Using this tag, Solana nodes can instantly access any historical block. On Arweave, full network data consistency isn’t required for participation. Instead, storage is incentivized. Arweave doesn’t use traditional linear chains but a graph-like structure. New blocks reference both the prior block and a randomly selected Recall Block. The Recall Block’s position depends on the prior block’s hash and current height—unknown until mining begins. To mine a new block, nodes must possess the Recall Block’s data to compute a proof-of-work hash meeting difficulty criteria—the first successful miner wins the reward, encouraging broad historical data retention. Fewer copies of a given block mean fewer competitors during nonce calculation—motivating miners to store rare blocks. Finally, to ensure permanent storage, Arweave implements Wildfire—a node scoring system. Nodes prefer peers who deliver historical data faster. Low-scoring nodes struggle to receive latest blocks and transactions promptly—disadvantaging them in PoW races.

Arweave block construction, image source: Arweave Yellow Paper

5. Comparative Analysis

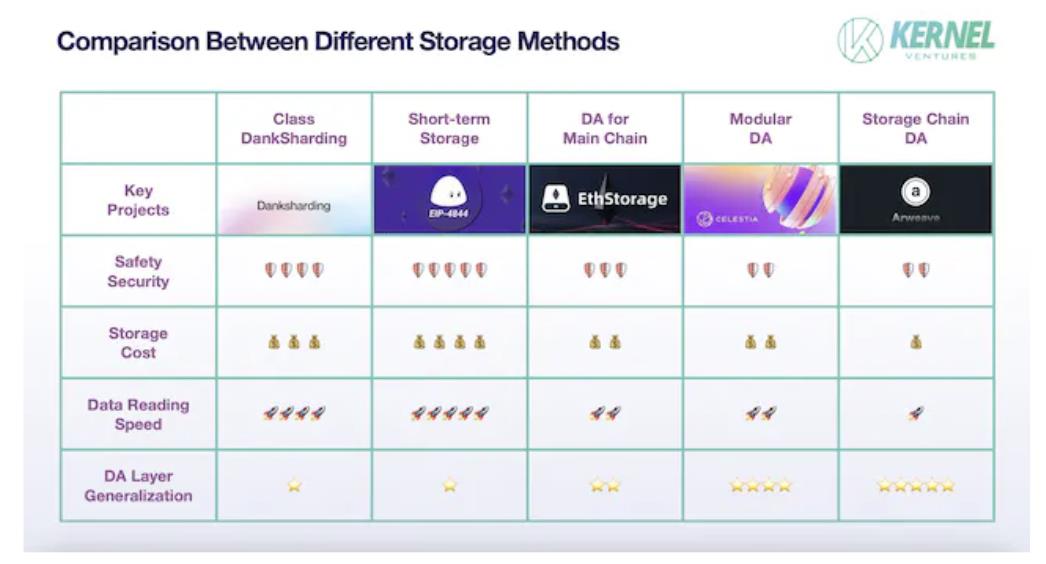

Next, we compare five storage solutions across the four DA performance dimensions.

Security: Major threats stem from data loss during transmission and malicious tampering by dishonest nodes. Cross-chain interactions—due to chain independence and non-shared states—are especially vulnerable. Moreover, Layer1s needing dedicated DA layers often have strong consensus communities, making them inherently more secure than generic storage blockchains. Thus, on-chain DA offers superior security. Once transmission security is ensured, focus shifts to retrieval safety. Considering only short-term historical data used for transaction validation: temporary storage networks replicate data universally—offering more redundancy than DankSharding-like schemes (which average 1/N replication across nodes). Greater redundancy reduces data loss risk and provides more verification references. Hence, temporary storage offers higher data security. Among third-party DAs, chain-specific DAs enjoy elevated security due to shared nodes with the mainchain—enabling direct relay-node-mediated transfers, avoiding vulnerabilities in other DA models.

Storage Cost: The biggest factor affecting cost is redundancy quantity. In on-chain DA’s short-term storage model, full network node synchronization means every new piece of data must be copied across all nodes—resulting in the highest storage cost. This high cost inherently limits applicability to temporary storage in high-TPS environments. Next come sharding-based models—both on-chain and third-party. Since mainchains typically have more nodes, their Blocks receive more backups—making on-chain sharding more expensive. The lowest-cost approach is incentivized storage on storage blockchain DAs—where redundancy fluctuates around a fixed constant. These systems also feature dynamic adjustment: increasing rewards to attract nodes to store under-replicated data—ensuring data safety economically.

Data Retrieval Speed: Retrieval speed depends heavily on data location (RAM vs. SSD), indexing paths, and node distribution. Location matters most—memory vs. SSD storage can differ by tens of times in speed. Storage blockchain DAs typically use SSDs because their workload includes not only DA data but also user-uploaded videos, images, and other high-memory personal data. Without SSDs, such chains couldn’t sustain massive storage demands or long-term retention. Next, third-party and on-chain DAs using memory-resident data differ: third-party DAs first search for index data on the mainchain, transfer it cross-chain, then return data via a bridge. In contrast, on-chain DA allows direct node queries—enabling faster retrieval. Finally, among on-chain DAs, sharded approaches require pulling Blocks from multiple nodes and reconstructing originals—making them slower than non-sharded short-term storage.

DA Layer Universality: On-chain DA has near-zero universality—it’s impractical to move data from one storage-constrained chain to another equally constrained one. Among third-party DAs, universality conflicts with chain-specific compatibility. For example, chain-specific DAs extensively modify node types and consensus to fit one chain—hindering communication with others. Within third-party DAs, storage blockchain DAs outperform modular DAs in universality. They boast larger developer communities and richer infrastructure, adapting better to diverse chains. Also, storage blockchain DAs actively pull data (e.g., packet capture) rather than passively receiving transmissions—enabling self-determined data encoding, standardized data flow management, easier cross-chain data integration, and improved storage efficiency.

Storage solution performance comparison, image source: Kernel Ventures

6. Conclusion

Blockchains today are transitioning from pure crypto applications toward more inclusive Web3 platforms—bringing not just richer on-chain projects. To support numerous concurrent applications on Layer1 while preserving GameFi and SocialFi user experiences, Ethereum and others adopt Rollups and Blobs to boost TPS. Meanwhile, new high-performance blockchains continue emerging. But higher TPS brings greater storage pressure. For massive historical data, various on-chain and third-party DA solutions have emerged—to adapt to growing storage demands. Each approach has strengths and weaknesses, fitting different contexts.

Payment-centric blockchains demand extremely high historical data security and don’t prioritize ultra-high TPS. For nascent chains, DankSharding-like storage offers massive capacity gains without sacrificing security. But for mature chains like Bitcoin—with established node networks—consensus-layer modifications carry unacceptable risks. Here, off-chain chain-specific DA provides a safer compromise. Importantly, blockchain functions evolve. Early Ethereum focused on payments and simple smart contract automation. As the ecosystem expanded, it embraced DeFi and SocialFi—becoming more general-purpose. Recently, the explosion of ordinals on Bitcoin caused mainnet fees to surge nearly 20× since August—reflecting insufficient transaction throughput. Traders now bid up fees to expedite processing. The Bitcoin community faces a trade-off: accept high fees and slow speeds, or sacrifice security for speed—contradicting its payment-system ethos. If the latter path is chosen, corresponding storage solutions must adapt accordingly.

Bitcoin mainnet transaction fee volatility, image source: OKLINK

For general-purpose blockchains pursuing higher TPS, historical data growth is immense. Long-term, DankSharding-like models struggle to keep pace with exponential TPS growth. Migrating data to third-party DAs becomes necessary. Chain-specific DAs offer maximum compatibility—potentially advantageous for single-chain use cases. But in today’s multi-chain landscape, cross-chain asset transfers and data exchanges are increasingly expected. Considering long-term ecosystem development, storing multiple chains’ histories on a single chain could eliminate many cross-chain verification risks—making modular DA and storage blockchain DA more attractive. Under comparable universality, modular DA specializes in blockchain DA services, introducing refined indexing for historical data classification—offering advantages over general storage blockchains. However, none of these consider the high cost and risk of consensus-layer upgrades on existing chains—where failures could create systemic vulnerabilities and erode community trust. Thus, for transitional scaling, simple on-chain temporary storage may suffice. Lastly, all above assumes real-world performance. But if a chain aims to grow its ecosystem and attract builders, it may favor foundation-backed projects—even if technically inferior. For example, despite potentially lower overall performance than storage blockchain solutions, Ethereum’s community may still prefer EthStorage—a foundation-supported Layer2—to strengthen the Ethereum ecosystem.

In summary, blockchain functionality grows increasingly complex—demanding ever-greater storage. When enough validator nodes exist, historical data need not be redundantly stored by every node—only sufficient replication to ensure relative safety. Simultaneously, blockchain roles are becoming more specialized: Layer1 handles consensus and execution, Rollups handle computation and validation, and separate chains manage data storage. Each component can focus on its role, unconstrained by others’ limitations. Yet determining how much data—or what proportion of nodes—should store history to balance safety and efficiency, and ensuring secure interoperability across chains, remain open questions requiring ongoing innovation. For investors, Ethereum’s chain-specific DA projects warrant attention—given Ethereum’s already vast supporter base, eliminating the need to rely on external communities. What’s needed now is deepening its own ecosystem—encouraging more projects to build on Ethereum. Conversely, emerging chains like Solana and Aptos lack mature ecosystems—making collaboration with other communities essential to build expansive cross-chain ecosystems and amplify influence. Thus, for newer Layer1s, universal third-party DAs deserve closer scrutiny.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News