Old Ambitions and New Visions: From Ethereum to Binance, the New "Trinity" Behind the Greenfield Curtain

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Old Ambitions and New Visions: From Ethereum to Binance, the New "Trinity" Behind the Greenfield Curtain

Starting from the era of Ethereum's "world computer," and taking the release of Binance Greenfield's whitepaper as a turning point toward a "new trinity" era, this narrative highlights the foundational roles of decentralized computing, decentralized storage, and decentralized communication within the Web3 ecosystem.

This is the first article in the "Trinity" series on Web3 social infrastructure. Starting from the Ethereum era of the "world computer" and taking the release of Binance Greenfield's whitepaper as a turning point into this "new trinity" era, it explores the foundational roles of decentralized computing, decentralized storage, and decentralized communication within the Web3 ecosystem. Decentralized computing has long been at the center of attention through debates between Layer 1 and Layer 2 solutions; the potential of decentralized storage has now been widely recognized thanks to strong backing from Binance; and the third piece—the "decentralized communication"—is poised to become the next major area of growth. This series follows that thread.

The Old Vision: The Original "Trinity" of Ethereum’s “World Computer” Era

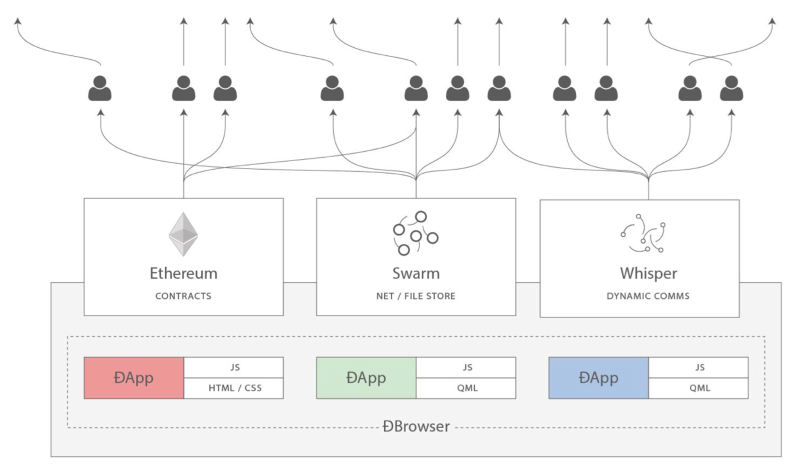

“The real Web 3.0 has yet to begin.” In 2014, Taylor Gerring made this declaration in his landmark article, “Building the Decentralized Web 3.0,” after reviewing 25 years of internet development. At the dawn of Ethereum, he envisioned what he called the "true Web 3.0" as a trinity:

-

Contracts: decentralized logic—smart contracts, or computation;

-

Swarm: decentralized storage—the domain now carried forward by Greenfield;

-

Whisper: decentralized messaging—the final missing puzzle piece among computation, storage, and communication.

Nearly a decade later, having traversed another third of its history, the fates of these three original pillars have diverged significantly. Ethereum (contracts) has grown a vast and vibrant ecosystem, becoming a true cornerstone. Swarm has struggled to define its narrative—from early community debates over whether it was reinventing the wheel already built by IPFS/Filecoin, to metaphors like “Ethereum is the world’s CPU, Swarm is the world’s hard drive,” and more recently, the concept of a “Web3 PC.” Living in the shadow of Ethereum’s success, Swarm has continually sought independent legitimacy and identity. As for Whisper, true to its name—like a whisper or murmur—it quickly faded into silence after brief discussion. Its entry has since been removed from the Ethereum wiki on GitHub, leaving behind an unresolved question around “communication.”

The many possibilities emerging from the Ethereum ecosystem have gradually eroded the explanatory power of the “world computer” slogan. Much like the decentralization ethos embedded in Ethereum itself, Ethereum’s history has largely been bottom-up construction rather than top-down architecture.

Rather than being a simultaneous set of next-generation internet components, the “trinity” is better understood as an asynchronous problem-solving chain: the issue of “computation” was solved first. Based on smart contracts, we developed entirely new application forms that relied on non-native storage and communication systems but were still functionally viable. Only when the ecosystem became sufficiently rich—generating and requiring enough data interaction—did the need arise to bring “storage” and “communication” to the forefront for dedicated development. Order matters.

Momentum accumulates regardless of human design. In 2023, “decentralized storage” and “decentralized communication” emerged suddenly into prominence. At this moment, Binance revived the old Ethereum “trinity,” making major moves in storage while closely watching developments in decentralized communication—an unmistakable response to the fact that both sectors had reached a critical threshold of accumulated momentum.

A New Vision: Binance Greenfield — Storage Is Just the Beginning

“Storage” is not a new story, but there is immense design space and technical imagination in what can be done “in the name of storage.” Different understandings of “storage” lead to fundamentally different “storage chains” or so-called “storage infrastructures.” There is no standard way to store data—only different attitudes toward data utilization, or more precisely, different “data philosophies.” Projects like Storj, Sia, Arweave, and IPFS/Filecoin each reflect their developers’ distinct views on data handling. As part of Binance’s broader expansion into the crypto world, Greenfield embodies a far-reaching and broadly impactful data philosophy. In crypto narratives, the distance between a product’s future vision and its current state often mirrors the depth of its historical roots—which explains why Binance, when launching Greenfield, traced back to Ethereum’s Swarm origins from several epochs ago. If there is no gap between narrative and execution, this reflects the ambition of Greenfield’s developers: starting with encrypted data, securing the data minefield, and building upstream across the entire data “supply chain.”

Storage is just the beginning. The essence of storage lies in data production relationships; changing how we store data also changes those production relationships.

From the outset, Binance aimed not merely to gain gatekeeper value by controlling data access points, but to create productive economic infrastructure at those entry-exit points—as a manufacturer, not just a guardian. Independent storage chains like Arweave focus primarily on extracting single权益 from static data, whereas Greenfield operates under the larger context of “BNB greater than Binance,” and is not an independent public chain but natively connected to BSC via a cross-chain bridge—giving it inherent dynamic transactional properties.

Unlocking the potential value of data requires examining the relationship between storage blockchains and smart contract blockchains. Traditionally, storage systems consist of two parts: an indexing system (for metadata) and an object storage system (for actual data), differing mainly in addressing methods and pre/post-indexing processing. Smart contracts, due to their programmability, offer significant advantages in data access control, computation, transactions, and agreements. Historically, storage blockchains and smart contract blockchains have remained separate domains—public storage chains generally lack the ability to compute or process data.

There are two approaches to bridging public storage chains with smart contract functionality:

-

Path One: Introduce an Ethereum-like Virtual Machine (EVM) into the storage chain to support smart contract execution. The VM runs outside storage nodes, reducing node load while increasing flexibility and programmability.

-

Path Two: Separate the computational and data storage components of the smart contract chain, handling execution and storage on sidechains. This avoids overburdening mainchain nodes and ensures reliability and security of data within decentralized storage.

Clearly, Filecoin and Greenfield represent these two distinct paths. Filecoin plans to launch smart contracts in March, evolving from a pure storage chain into a more complete Layer 1—following Path One. Greenfield, backed by BSC as a sidechain of the BNB Chain, implements Path Two by separating computation and storage. By enabling smart contract compatibility, Greenfield unlocks the economic potential of data itself—not just placing an economic layer on the storage chain (as Arweave does), but automatically extracting ownership rights and derivative rights such as access, adaptation, reuse, and distribution. "Rights generate value"—by establishing clear data ownership, Greenfield opens up massive opportunities for utility and financialization. Just as DeFi introduced yield farming, once data becomes a broad asset class, we may see yield farming models specifically tailored to data types.

Decentralized Communication: The Final Piece of the Trinity

Having unfolded the flat “trinity” vision into a three-dimensional Web3 problem-solving pathway, we arrive at the final stage: decentralized communication. As the last to arrive—and the closest to end users—among computation, storage, and communication, “decentralized communication” remains largely unexplored territory, full of untapped potential. Few have cultivated this ground, yet as decentralized communication technologies quietly mature through sustained effort, the full realization of this ecological niche is only a matter of time.

Binance recently hosted a discussion titled “Why Web3 Communication Matters,” bringing decentralized communication back into the spotlight. If storage represents control over historical network data production and interaction, then communication represents control over *current* network data production and interaction. Instant messaging (IM), notifications, and secure communications between wallets and dApps all rely on decentralized communication infrastructure. Broadly speaking, decentralized communication spans three dimensions: person-to-person, person-to-software, and software-to-software. Its trustless nature enables communication that can be “never terminated”—no centralized entity can monopolize communication between two parties, nor can any party extract meaningful information for secondary use. Only when decentralized communication combines with encryption technology can we truly fulfill the cypherpunk independence宣言 of the turn of the century—making the internet not only spiritually but technically independent from centralized institutions’ surveillance and manipulation, ensuring security-based autonomy and creating a parallel cyber-space with full spatial dimensionality (tamper-proof) and temporal continuity (unstoppable).

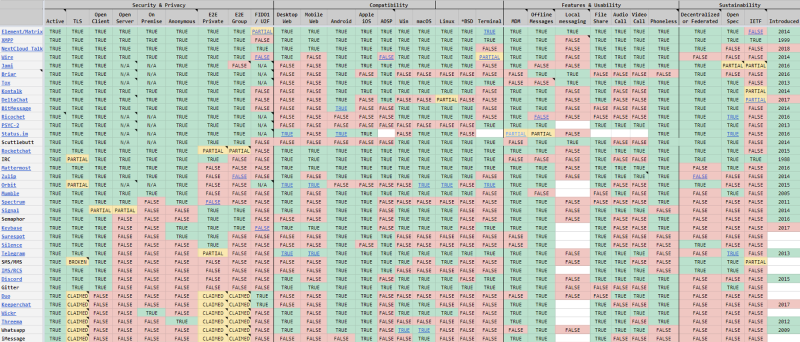

Comparison of communication protocol dimensions before the emergence of usable native Web3 decentralized communication protocols,[Illustration: Prehistory of Decentralized Communication]

Decentralized communication is the key step in Web3’s evolution from asset-centric to user-centric, marked by the emergence of a new economic layer. In Web2, the monetization rights of “user engagement” were monopolized by centralized platforms, manifested in their tight control over attention allocation and its commercial extensions—primarily advertising. The precision of Web2’s attention exploitation is evident in how ads are segmented down to size, display duration, placement, and even presentation style. Yet “user engagement,” as the primary upstream value source, is repeatedly sliced and sold. The economic layer of decentralized communication, however, is user-centric: users will decide how their engagement is monetized—whether to receive notifications, what kind, how much attention they give, and what equivalent value they receive in return. This represents the final and most crucial implementation of “data ownership”: decentralized computing makes data ownership technically possible; decentralized storage secures ownership of historical data and enables future access; and decentralized communication ensures ownership of real-time interactive data centered on user participation.

In the next article of this series, we will focus on “decentralized communication,” beginning with the technical details of Nostr—the first fully decentralized social communication protocol to achieve mass appeal—and explain why social communication protocols, as one of the pillars of decentralized infrastructure, possess ecological potential comparable to that of decentralized computing and decentralized storage, and where this journey might lead next.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to ArNostr (Weibo), George Zhang Tengji from Unipass, and Sponge Aaron from Plancker DAO for their contributions to this article.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News