The Survival of ZKVM: A Comprehensive Analysis of Factional Rivalries

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Survival of ZKVM: A Comprehensive Analysis of Factional Rivalries

In the past year of 2022, the main discussions around rollups seemed to focus on ZkEVM, but don't forget that ZkVM is another scaling approach as well.

Author: Bryan, IOSG Ventures

Special thanks to Xin Gao, Boyuan from p0xeidon, Daniel from Taiko, and Sin7Y for their support and feedback on this article!

Table of Contents

Circuit Implementation in ZKP Systems - Circuit-Based vs VM-Based

Design Principles of ZKVMs

Comparison Among STARK-Based VMs

Why Risc0 is Exciting

Preface:

In 2022, much of the rollup discussion centered around ZkEVM. However, we must not overlook ZKVM as another scalability approach. While ZkEVM is not the focus of this article, it's worth reflecting on several key differences between ZkVM and ZkEVM:

1. Compatibility: Although both aim at scaling, their focuses differ. ZkEVM emphasizes direct compatibility with existing EVM, whereas ZKVM prioritizes full scalability—optimizing dapp logic and performance above all. Compatibility is secondary. Once the foundation is solid, EVM compatibility can be added later.

2. Performance: Both face foreseeable bottlenecks. ZkEVM’s main bottleneck stems from the overhead incurred by maintaining EVM compatibility—a design not inherently suited for zero-knowledge proof systems. ZKVM’s bottleneck arises from introducing an instruction set (ISA), which leads to more complex final constraints.

3. Developer Experience: Type II ZkEVMs (e.g., Scroll, Taiko) emphasize bytecode-level compatibility, meaning any EVM bytecode and higher-level code can generate corresponding zero-knowledge proofs via ZkEVM. For ZKVMs, there are two directions: one involves building a custom DSL (like Cairo); the other aims to support mature languages like C++ or Rust (like Risc0). In the future, native Solidity Ethereum developers will likely migrate seamlessly to ZkEVM, while more powerful and advanced applications will run on ZKVMs.

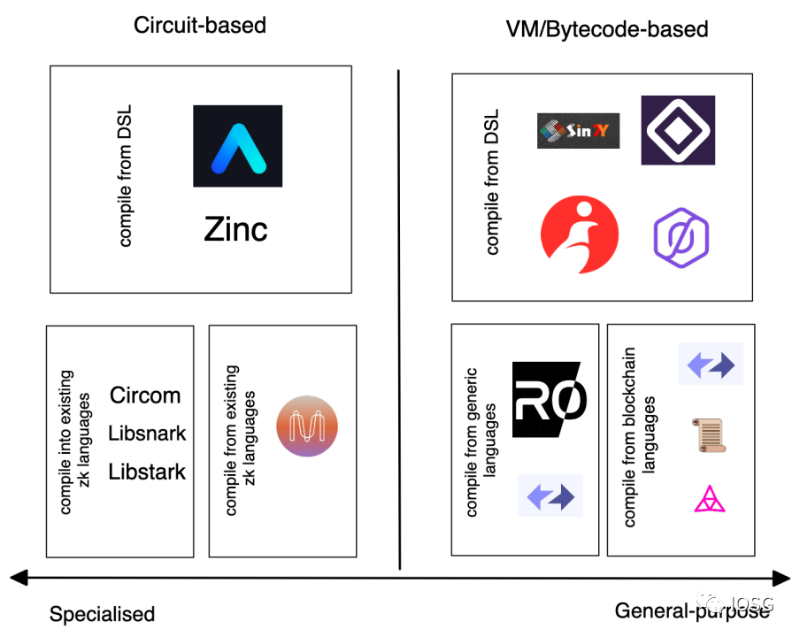

Many may recall this diagram—CairoVM stands apart from the ZkEVM factional struggle due to fundamentally different design philosophies.

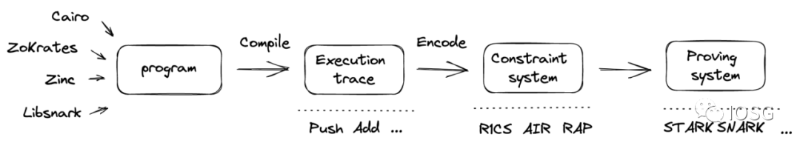

Before discussing ZKVM, let’s first consider how to implement a ZK proof system in blockchain. Broadly speaking, there are two approaches to circuit implementation—circuit-based systems and vm-based systems.

First, circuit-based systems directly convert programs into constraints and feed them into a proving system. VM-based systems execute programs through an instruction set (ISA), generating an execution trace during runtime. This trace is then mapped into constraints before being fed into the proving system.

In a circuit-based system, computation is constrained per machine executing the program. In a VM-based system, the ISA is embedded within the circuit generator, producing constraints for any given program. The circuit generator has fixed rules regarding ISA, cycle count, memory usage, etc. The VM provides universality—any machine can run a program as long as it fits within these constraints.

A ZKP program in a virtual machine typically goes through the following process:

Image source: Bryan, IOSG Ventures

Pros and Cons:

- From a developer’s perspective, developing on a circuit-based system usually requires deep understanding of each constraint's cost. In contrast, when writing programs for a VM, the circuit is static; developers only need to focus on instructions.

- From a verifier’s perspective, assuming the same pure SNARK backend, circuit-based and VM-based systems differ significantly in generality. Circuit systems generate different circuits for different programs, while VMs use the same circuit across programs. This means that in a rollup, a circuit-based system would require deploying multiple verifier contracts on L1.

- From an application standpoint, VMs embed memory models into their design, enabling more complex application logic, while circuit-based systems aim primarily at optimizing program performance.

- From a system complexity perspective, VMs introduce greater complexity—including memory models, host-guest communication—while circuit-based systems remain simpler and more minimal.

Below is a preview of current L1/L2 projects based on circuit and VM approaches:

Image source: Bryan, IOSG Ventures

VM Design Principles

There are two key design principles in a VM:

First, ensure correct program execution—i.e., outputs (constraints) correctly match inputs (programs). This is generally achieved via the ISA.

Second, ensure the compiler functions correctly when translating high-level code into appropriate constraint formats.

1. ISA Instruction Set

Defines how the circuit generator operates. Its primary role is to correctly map instructions into constraints, which are then passed to the proving system. Most zk systems use RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computing). There are two choices for ISA:

The first is a custom ISA, as seen in Cairo’s design. Generally, there are four types of constraint logic:

The core design goal of a custom ISA is minimizing the number of constraints, allowing faster execution and verification.

The second option uses existing ISAs, as adopted in Risc0. Beyond aiming for concise execution time, existing ISAs (like RISC-V) offer additional benefits such as frontend language and backend hardware friendliness. A potential concern is whether existing ISAs might lag in verification time, since fast verification wasn't a primary design goal of RISC-V.

2. Compiler

Broadly speaking, a compiler progressively translates programming languages into machine code. In a ZK context, it refers to compiling high-level languages like C, C++, or Rust into low-level representations suitable for constraint systems (e.g., R1CS, QAP, AIR). There are two approaches:

Designing a compiler based on existing zk circuit representations—e.g., using libraries like Bellman or low-level languages like Circom. To unify various formats, compilers like Zokrates (which also acts as a DSL) aim to provide an abstraction layer capable of targeting multiple lower-level representations.

Building upon existing compiler infrastructure. The core idea is leveraging an intermediate representation (IR) compatible with multiple frontends and backends.

Risc0’s compiler is built on multi-level intermediate representation (MLIR), capable of generating multiple IRs (similar to LLVM). Different IRs offer flexibility, as each has distinct optimization goals—some tailored for hardware, allowing developers to choose based on needs. Similar ideas appear in vnTinyRAM and TinyRAM using GCC. zkSync is another example utilizing compiler infrastructure.

Additionally, some zk-specific compiler infrastructures exist, such as CirC, which borrows concepts from LLVM.

Beyond these two critical components, several other factors must be considered:

1. Trade-off between system security and verifier cost

Higher bit-length implies stronger security but increases verification cost. Security manifests in components like key generators (e.g., elliptic curves in SNARKs).

2. Frontend and backend compatibility

Compatibility depends on the effectiveness of the circuit’s intermediate representation (IR). The IR must balance correctness (matching input-output behavior and conforming to the proof system) and flexibility (supporting diverse frontends and backends). If an IR was originally designed for low-degree constraint systems like R1CS, compatibility with higher-degree systems like AIR becomes challenging.

3. Hand-crafted circuits for efficiency

A downside of general-purpose models is inefficiency for simple operations that don’t require complex instructions.

A brief overview of earlier theoretical developments:

Pre-Pinocchio: Achieved verifiable computation, but with very slow verification times.

Pinocchio Protocol: Provided theoretical feasibility in terms of verifiability and verification speed (verifier time shorter than execution time), forming the basis of circuit-based systems.

TinyRAM Protocol: Compared to Pinocchio, TinyRAM behaves more like a VM, introducing an ISA and thus overcoming limitations such as RAM access and control flow.

vnTinyRAM Protocol: Makes key generation independent of individual programs, adding generality. It extends the circuit generator to handle larger programs.

All the above models use SNARK as their backend proof system. However, especially when dealing with VMs, STARK and Plonk appear more suitable backends, primarily because their constraint systems better suit CPU-like logic.

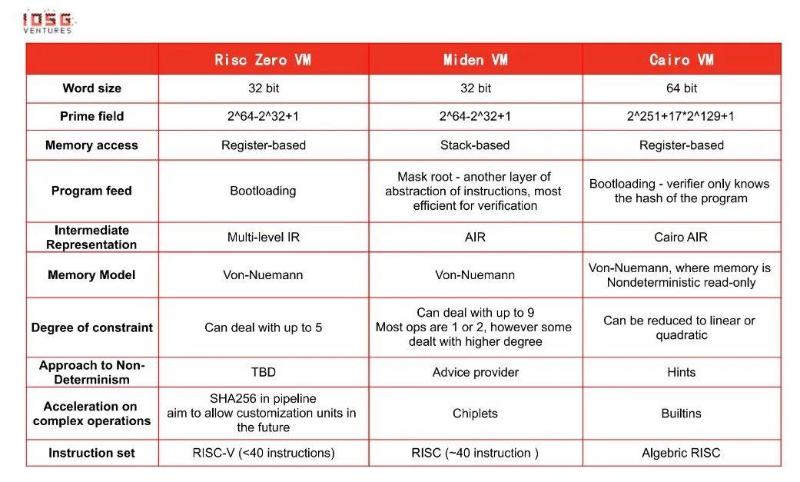

Next, this article introduces three STARK-based VMs: Risc0, MidenVM, and CairoVM. In short, beyond sharing STARK as a proving system, they differ significantly:

Risc0 leverages RISC-V for instruction set simplicity. Risc0 compiles via MLIR—an LLVM-IR variant—supporting multiple general-purpose languages like Rust and C++. RISC-V also offers additional advantages, including hardware friendliness.

Miden aims for compatibility with the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), essentially functioning as an EVM rollup. Miden currently has its own programming language but plans to support Move in the future.

Cairo VM is developed by Starkware. The STARK proving system used across these three platforms was invented by Eli Ben-Sasson, now president of Starkware.

Let’s delve deeper into their differences:

*How to Read the Table Above? Some Notes…

●Word size – Since these VMs rely on AIR-based constraint systems, which resemble CPU architectures, choosing standard CPU word sizes (32/64-bit) makes sense.

●Memory access – Risc0 uses registers mainly because the RISC-V ISA is register-based. Miden relies heavily on stacks for data storage, as AIR naturally aligns with stack operations. CairoVM avoids general-purpose registers because memory access costs are relatively low in the Cairo model.

●Program feed – Different methods involve trade-offs. For instance, the Merkle root method requires decoding instructions during processing, increasing prover cost for programs with many steps. Bootloading attempts to balance prover and verifier costs while preserving privacy.

●Non-determinism – Non-determinism is a key feature of NP-complete problems. Leveraging non-determinism helps accelerate verification of past executions. Conversely, it adds more constraints, resulting in some verification overhead.

●Acceleration on complex operations – Certain computations are slow on CPUs. Examples include bitwise operations (XOR, AND), hash functions (e.g., ECDSA), and range checks—operations native to blockchains/crypto but not to CPUs (except bitwise ops). Implementing these directly via DSLs can easily exhaust proof cycles.

●Permutation/multiset – Widely used in most zkVMs for two purposes: 1) Reducing verifier cost by avoiding full execution trace storage; 2) Proving the verifier knows the complete trace.

Finally, I’d like to discuss Risc0’s current development and why it excites me.

Risc0’s Current Development:

a. A proprietary compiler infrastructure called "Zirgen" is under development. It will be interesting to compare Zirgen against existing zk-specific compilers.

b. Promising innovations such as field extension, enabling stronger security parameters and operations over larger integers.

c. Recognizing challenges in integrating ZK hardware and software companies, Risc0 employs a hardware abstraction layer to facilitate better hardware development.

d. Still a work-in-progress! Active development continues!

- Support for hand-crafted circuits and multiple hash algorithms. Currently, a dedicated SHA256 circuit is implemented, though it doesn’t meet all requirements yet. The author believes optimal circuit selection depends on Risc0’s target use cases. SHA256 is a strong starting point. On the other hand, ZKVMs offer flexibility—users don’t have to support Keccak if they don’t want to :)

- Recursion: A major topic, beyond the scope of this report. As Risc0 targets increasingly complex programs, recursion becomes essential. To further support recursion, GPU acceleration on the hardware side is currently being explored.

- Handling non-determinism: An inherent attribute ZKVMs must manage—unlike traditional VMs. Non-determinism can speed up VM execution. While MLIR excels at solving issues in traditional VMs, how Risc0 integrates non-determinism into its ZKVM design remains to be seen.

WHAT EXCITES ME:

a. Simple and Verifiable!

In distributed systems, PoW requires high redundancy because trust is lacking—thus requiring repeated computation for consensus. With zero-knowledge proofs, achieving state agreement should be as trivial as agreeing that 1+1=2.

b. More Practical Use Cases:

Beyond direct scaling, new exciting applications become feasible—zero-knowledge machine learning, data analytics, and more. Compared to domain-specific ZK languages like Cairo, Rust/C++ are more versatile and powerful, enabling more Web2-style applications to run on Risc0 VM.

c. More Inclusive/Mature Developer Community:

Developers interested in STARKs and blockchain no longer need to learn a new DSL—they can use familiar languages like Rust/C++.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News