Thoughts on DeFi Token Economics: Staking Rewards, Token Burning, and Long-termism

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Thoughts on DeFi Token Economics: Staking Rewards, Token Burning, and Long-termism

Why DeFi Token Economics Needs a Rethink: What Will the New Model Look Like?

Author: Will Comyns, Shima Capital

Translation: TechFlow

DeFi has long struggled with token value accrual and retention. Now is the perfect time to address this issue.

This article explains why DeFi tokenomics need adjustment and what new models might look like.

Tokens as Claims on Revenue

Holding tokens grants governance rights, which provides a compelling reason to hold—but many tokens still struggle to effectively accumulate and retain value.

As a result, there is growing consensus within the Web3 community that tokens must begin offering both revenue sharing and governance rights.

Notably, tokens that provide income-sharing to holders may appear more like securities.

Many use this point to oppose revenue distribution in DeFi tokens, but without such a change, DeFi will continue to exist primarily as a speculative market for the masses.

If DeFi is to achieve mainstream legitimacy, it cannot be the case that all token prices move nearly in lockstep—because under such conditions, differing profitability across protocols isn’t reflected in token price movements.

While one concern is that enhancing token capture of protocol revenue increases its security-like attributes, the argument that restricting tokens to governance rights alone is better for long-term adoption is clearly flawed.

As summarized by DeFi Man, protocols currently use two main methods to distribute revenue to token holders:

1. Repurchasing their native token from the market and (1) distributing it to stakers, (2) burning it, or (3) holding it in the protocol treasury.

2. Redistributing protocol revenue directly to token holders.

Yearn.finance stirred waves last December when it announced an update to its tokenomics and buyback program, leading to an 85% short-term rebound in YFI price. While only temporary, the strong desire for improved token models was evident.

However, in the long run, distributing a share of protocol revenue is clearly superior to token buybacks.

The primary goal of any DAO should be maximizing long-term value for token holders. As Hasu wrote, "Every dollar a protocol owns or receives as revenue should be allocated to its most valuable use." Therefore, a DAO should only buy back its native token if the token is undervalued.

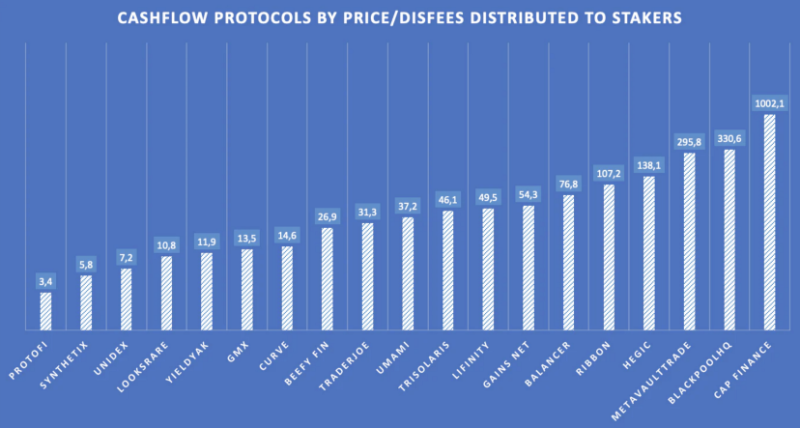

We can build a valuation framework for these tokens based on the cash flows established by protocols that share revenue with native token stakers. By evaluating incentives paid to stakers, we can assess token valuations while also re-evaluating incentives paid to liquidity providers (LPs).

When analyzing protocol-generated revenue, a common approach divides revenue into two categories: protocol and LP. Evaluating token value based on revenue distributed to token stakers reveals the true nature of LP income—as operating costs.

An increasing number of protocols have begun establishing revenue-sharing with governance token stakers. GMX, in particular, has set a new precedent. GMX is a zero-slippage, decentralized perpetual futures and spot exchange built on Avalanche and Arbitrum. GMX stakers receive 30% of protocol fees, while LPs receive the remaining 70%, paid in $ETH and $AVAX rather than $GMX.

Much like growth stocks retaining earnings instead of paying dividends, some argue that paying out fees to token stakers rather than reinvesting them into the protocol treasury harms long-term development. However, GMX demonstrates this isn't necessarily true. Despite sharing revenue with stakers, GMX continues innovating and launching new products like X4 and PvP AMM.

Generally speaking, reinvestment only makes sense if a protocol or company can deploy capital more effectively than distributing it to stakeholders.

DAOs are often inefficient at capital management and rely on a decentralized network of contributors beyond their core teams.

For these two reasons, most DAOs should begin distributing revenue to stakeholders earlier than their centralized Web2 counterparts.

Learning from the Past: Burning and Staking

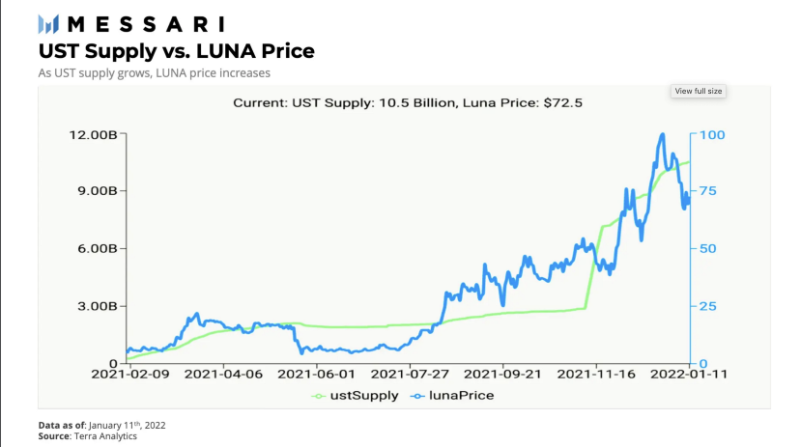

Terra

Despite the damage caused by Terra’s collapse, it offers strong educational value and provides reference points for shaping sustainable token models.

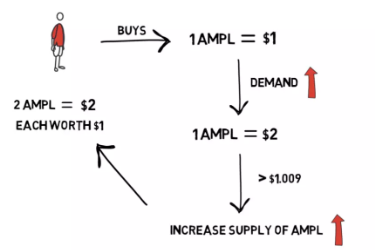

In the short term, Terra demonstrated that token burning can be an effective mechanism for value accrual. Of course, this didn’t last long. By manipulating the burn rate of $LUNA through the Anchor Protocol, Terra caused unwarranted and unsustainable reductions in $LUNA supply. While supply manipulation lit the fuse of self-destruction, Terra ultimately collapsed because even after a series of supply contractions, the expansion of $LUNA circulation remained too easy.

(3,3) Tokenomics

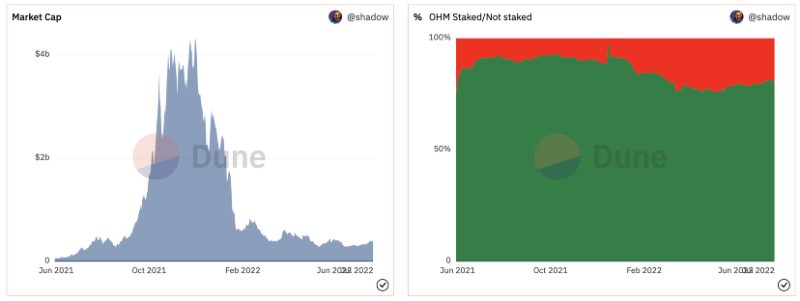

The decline of (3,3) economics at the end of 2021 also offered important lessons.

OlympusDAO proved that staking a large portion of a protocol’s native token could drive significant short-term price appreciation.

However, we later saw that if stakers can exit with minimal consequences, they do so at the expense of other stakers.

Rebases were implemented to encourage participation in staking. If users stake, they receive “free” tokens to maintain their current market cap share.

In reality, anyone who wants to sell doesn’t care about dilution upon unstaking.

Due to the nature of rebases, early entrants and early exits profit by using newcomers as their exit liquidity.

To implement sustainable staking in the future, stakers must face harsher penalties for unstaking. Additionally, those who unstake later should benefit more than those who unstake earlier.

ve Tokenomics

The common flaw among previous failed token models is lack of sustainability. Curve’s ve model is a widely adopted token design that attempts to implement a more sustainable staking mechanism by incentivizing token holders to lock their tokens for up to four years in exchange for inflationary rewards and expanded governance power.

Despite its short-term effectiveness, the model has two major drawbacks:

-

Inflation acts as an indirect tax on all token holders and negatively impacts token value.

-

Massive sell-offs may occur when lock-up periods finally expire.

When comparing ve and (3,3), they share a similarity: both offer inflationary rewards in exchange for staking commitments. Lock-ups can suppress selling pressure in the short term, but once inflation rewards lose value over time and lock-up periods end, massive sell-offs emerge.

In a sense, ve resembles time-locked liquidity mining.

The Ideal Token Model

Unlike past unstable token models, the ideal future token model will sustainably align incentives for users, investors, and founders. When Yearn.finance proposed its ve-inspired tokenomics plan (YIP-65), it claimed to have built its model around several key incentives—some of which can apply to other projects:

-

Implement token buybacks (distribute revenue to token holders)

-

Build a sustainable ecosystem

-

Encourage long-term thinking

-

Reward loyal users

With these principles in mind, I propose a new token model that uses taxation to provide stability and value accumulation.

Revenue and Taxation Model

I’ve previously established that an ideal token design grants holders governance rights and a share of protocol revenue when staked. In this model, users pay a “tax” to unlock their tokens instead of relying on fixed lock-up periods. While taxation/penalties on unstaking aren’t unique to this model, the specific tax mechanism is.

The unlock tax is determined as a percentage of the staked tokens. A portion of the taxed tokens is proportionally distributed to other stakers in the pool, while another portion is burned. For example, if a user stakes 100 tokens with a 15% tax rate, they pay 15 tokens to unstake. In this case, ⅔ of the tax (10 tokens) would be distributed proportionally to other stakers in the pool, while ⅓ (5 tokens) would be burned.

This system rewards the most loyal users—the longer someone holds, the greater their benefit. It also reduces downside volatility during market sell-offs.

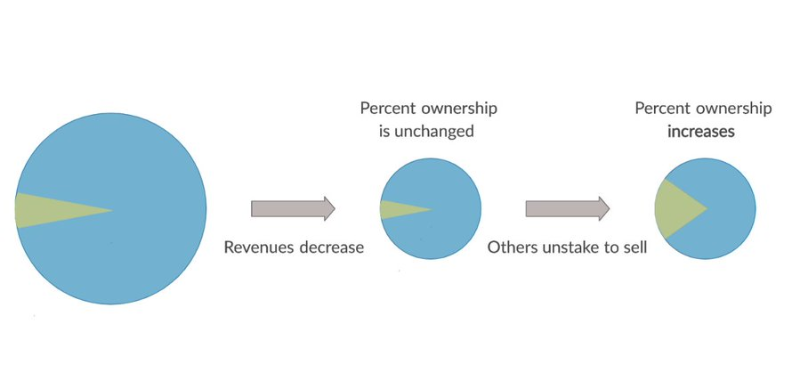

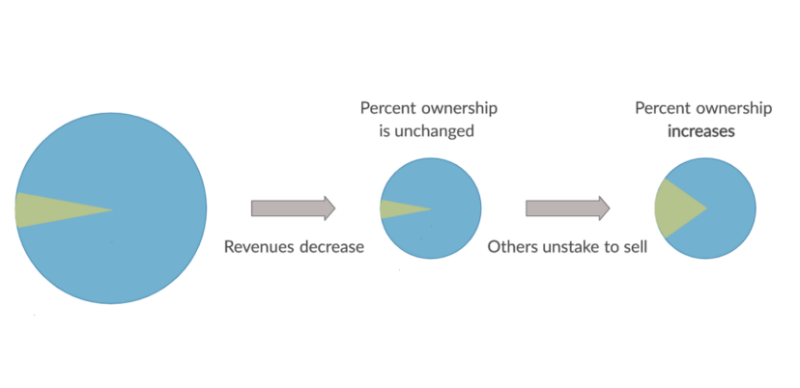

Theoretically, if someone unstakes, it’s because revenue has declined or is expected to decline soon.

Viewing protocol revenue as a pie, declining revenue means the overall pie shrinks. In the above example, taxing tokens and redistributing them to those who remain staked increases their slice, mitigating their losses.

The burned ⅓ creates deflationary pressure on token supply, boosting overall token price. Over time, burning leads to token supply following an exponential decay pattern. The chart above shows how losses could be reduced for those who continue staking during a market sell-off, while the chart below illustrates how the burned tax portion reduces losses for all token holders, whether staked or not.

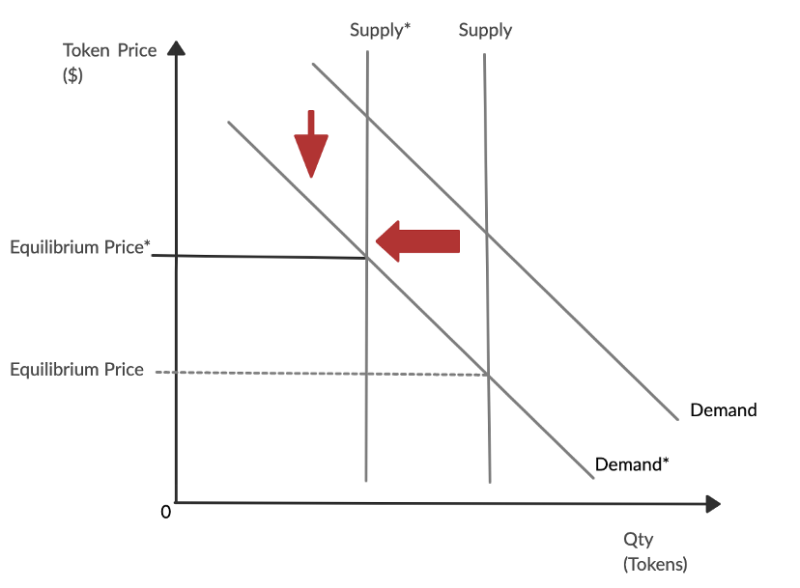

The chart reflects inward-shifting demand due to declining protocol revenue. As a result, some investors unstake to sell. During unstaking, part of their tokens are burned. This burning mechanism reduces total token supply and shifts the supply curve leftward, resulting in a smaller decline in token price.

The worst-case scenario for this model occurs if protocol revenue drops sharply and whales decide to unstake and dump their tokens. Given that Convex currently controls 50% of all veCRV, this could mean half the tokens being unlocked and sold. Even with taxes, if most tokens were locked before the sell-off, the token price would likely crash in the short term.

This underscores that no matter what staking/burning mechanism a protocol implements, if the underlying protocol fails to generate revenue, the token remains worthless. However, assuming in this scenario that protocol revenue rebounds soon, those who remain staked after the whale dump would gain 5% of total token supply, while total supply decreases by 2.5%, significantly increasing their share of future revenue.

Since whales are inevitable, a further refinement of this proposed tax could be a progressive tax. While challenging to implement, protocols might leverage analytics tools like Chainalysis or develop internal systems to enforce it. It's unclear what the best solution for progressive taxation would be—it’s clear, however, that more research and development are needed to answer this question.

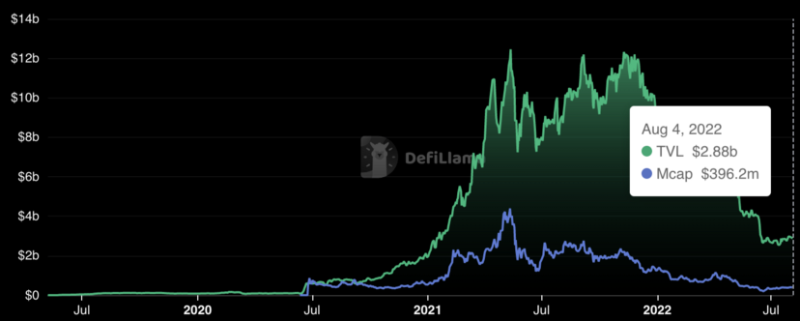

Whether implementing a flat or progressive tax, protocols should adopt this revenue-sharing and taxation model only after accumulating substantial TVL. In the early lifecycle of a protocol, priority should be on bootstrapping liquidity, dispersing tokens, and building traction. Thus, in early stages, token models centered on liquidity mining may positively support long-term growth.

However, as a protocol matures, its priorities must shift from TVL acquisition to creating long-term, sustainable token value accrual. Therefore, it must adopt a different token model that better aligns economic incentives with these new goals.

Compound exemplifies a protocol that failed to evolve its token design to match its maturity stage. Despite accumulating significant TVL and generating substantial revenue, very little of this value is captured by $COMP holders. In an ideal world, a protocol’s profitability should reflect in its token price—but in reality, this happens only occasionally.

Conclusion

The most important aspect of this proposed token model is its sustainability. Staking incentives are more sustainable because they favor those who “enter early, exit late,” rather than the typical first-in-first-out (FIFO) principle.

The token-burning component further enhances sustainability because it is unidirectional (supply can only contract). If recent market downturns have taught us anything, it’s that sustainability matters.

While the path forward for Web3 will be driven by disruptive innovation and broader user adoption, none of this is possible without more sustainable token models capable of effectively accruing and retaining value.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News