The Year Token Economics Was Proven False

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Year Token Economics Was Proven False

The two sides permeate each other, and the boundaries gradually disappear.

Text by: Kaori

Edited by: Sleepy.txt

When Bitcoin ETFs were approved in early 2024, many crypto practitioners jokingly referred to each other as "honored U.S. stock traders." But when the New York Stock Exchange began planning blockchain-based stock trading and 24/7 markets, with tokenization becoming part of traditional finance agendas, crypto talent belatedly realized that the crypto industry had not conquered Wall Street.

On the contrary, Wall Street had always bet on convergence, and is now gradually transitioning into an era of mutual acquisition: crypto companies buying traditional financial licenses, clients, and compliance capabilities; traditional finance acquiring crypto’s technology, infrastructure, and innovation capacity.

The two sides are increasingly interpenetrating, and boundaries are fading. In three to five years, there may no longer be a distinction between crypto firms and traditional financial institutions—only financial firms.

This process of assimilation and integration is being codified through the Digital Asset Market Structure Clarification Act (hereinafter referred to as the CLARITY Act), legally reshaping a once-wild crypto space into a form familiar to Wall Street. The first concept under reform is “token rights”—a purely crypto-native idea that never gained traction like stablecoins did.

The Era of Either/Or

For a long time, crypto practitioners and investors have lived in a state of anxious limbo, frequently facing enforcement-style regulation from governments around the world.

This tension has not only stifled innovation but also placed token buyers in an awkward position—they hold tokens, yet possess only hollow token rights. Unlike shareholders in traditional financial markets, token holders lack legally protected rights to information or recourse against insider trading by project teams.

Thus, when the CLARITY Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives with strong bipartisan support in July last year, the entire industry placed high hopes on it. The market's core demand was clear: define whether tokens are digital commodities or securities, ending the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC)'s years-long jurisdictional tug-of-war.

The bill stipulates that only fully decentralized assets with no actual controlling party can be classified as digital commodities under CFTC oversight—akin to gold or soybeans. Any asset showing signs of centralized control or raising funds through promises of returns would be categorized as restricted digital assets or securities, falling squarely under the SEC’s strict regulatory authority.

This is favorable for networks like Bitcoin and Ethereum, which long ago shed centralized control. But for most DeFi projects and DAOs, it’s nearly catastrophic.

The law requires all intermediaries involved in digital asset transactions to register and implement rigorous anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) procedures—something impossible for DeFi protocols running entirely on smart contracts.

The summary document explicitly states that certain decentralized financial activities related to blockchain network maintenance will be exempted, though authorities retain power to enforce anti-fraud and anti-manipulation rules.

This is a classic regulatory compromise: coding and front-end development remain permissible, but once you engage in trade matching, yield distribution, or intermediary services, heavier regulations kick in.

Precisely because of this compromise, the CLARITY Act failed to bring real peace to the industry after its passage in summer 2025. Instead, it forced every project to confront one brutal question anew—what exactly are you?

If you claim to be a decentralized protocol complying with the CLARITY Act, your token cannot carry real economic value. If you don’t want to shortchange token holders, then you must acknowledge equity-like structures—and subject your tokens to scrutiny under securities law.

People Yes, Tokens No

This dilemma played out repeatedly throughout 2025.

In December 2025, a merger announcement triggered starkly different reactions across Wall Street and the crypto community.

Circle, the world’s second-largest stablecoin issuer, announced the acquisition of Interop Labs—the core development team behind the cross-chain protocol Axelar. To traditional financial media, this was a standard talent acquisition: Circle secured a top-tier cross-chain engineering team to enhance USDC’s multi-chain liquidity.

Circle’s valuation strengthened accordingly, while Interop Labs’ founders and early equity investors exited satisfied, receiving cash or Circle shares.

But in the cryptocurrency secondary market, the news sparked panic selling.

Investors dissecting the deal terms discovered that Circle acquired only the development team, explicitly excluding the AXL token, the Axelar network, and the Axelar Foundation.

This revelation instantly dismantled earlier positive expectations. Within hours of the announcement, the AXL token erased all gains previously driven by acquisition rumors—and plunged further into steep losses.

For a long time, investors in crypto projects operated under a shared narrative: buying a token equaled investing in a startup. As the development team succeeded and protocol usage grew, the token’s value would rise accordingly.

The Circle acquisition shattered this illusion, legally and practically declaring that the development company (Labs) and the protocol network (Network) are entirely separate entities.

“It’s legal robbery,” wrote an investor holding AXL for over two years on social media. Yet he could sue no one—because in prospectuses and whitepapers, tokens were never promised residual claims over the developing company.

Looking back at 2025’s acquisitions of tokenized crypto projects, these deals typically transferred technical teams and underlying architecture—but excluded tokenholder权益—inflicting major blows to investors.

In July, Kraken’s Layer 2 network Ink acquired Vertex Protocol’s engineering team and its underlying trading infrastructure. Soon after, Vertex Protocol announced service termination, rendering its VRTX token obsolete.

In October, Pump.fun acquired the trading terminal Padre. Simultaneously, the project team declared the PADRE token void, with no future plans.

In November, Coinbase acquired the trading terminal technology built by Tensor Labs—a deal that similarly excluded any rights tied to the TNSR token.

At least during this wave of 2025 M&A activity, more and more transactions favored buying teams and technologies while discarding tokens altogether. This growing trend has left increasing numbers of crypto investors furious: “Either give tokens the same value as stocks, or stop issuing them.”

DeFi’s Dilemma of Revenue Sharing

If Circle’s case represents external acquisition-induced tragedy, Uniswap and Aave illustrate internal conflicts that have long plagued the crypto market at different stages.

Aave, long considered the king of DeFi lending, plunged into a fierce internal war at the end of 2025 over who owns the money—the conflict centering on front-end revenue generated by the protocol.

Most users do not interact directly with blockchain smart contracts but instead use the web interface developed by Aave Labs.

In December 2025, the community noticed that Aave Labs had quietly modified its front-end code, redirecting high transaction fees from token swaps conducted via its website to the company’s own corporate account—rather than to the treasury of the decentralized autonomous organization, Aave DAO.

Aave Labs justified this move using conventional business logic: “We built the site, paid for server costs, and bear compliance risks—monetizing traffic should belong to the company.” But to token holders, this felt like betrayal.

“Users come for the Aave decentralized protocol, not your HTML page,” critics argued. The controversy caused Aave’s token market cap to evaporate by $500 million in short order.

Although both parties eventually reached a compromise under intense public pressure—with Labs committing to propose a mechanism to share non-protocol revenues with token holders—the rift was irreparable.

The protocol might be decentralized, but the access point remains centralized. Whoever controls the entry point holds de facto taxing power over the protocol economy.

Meanwhile, Uniswap, the dominant decentralized exchange, had to resort to self-mutilation in pursuit of compliance.

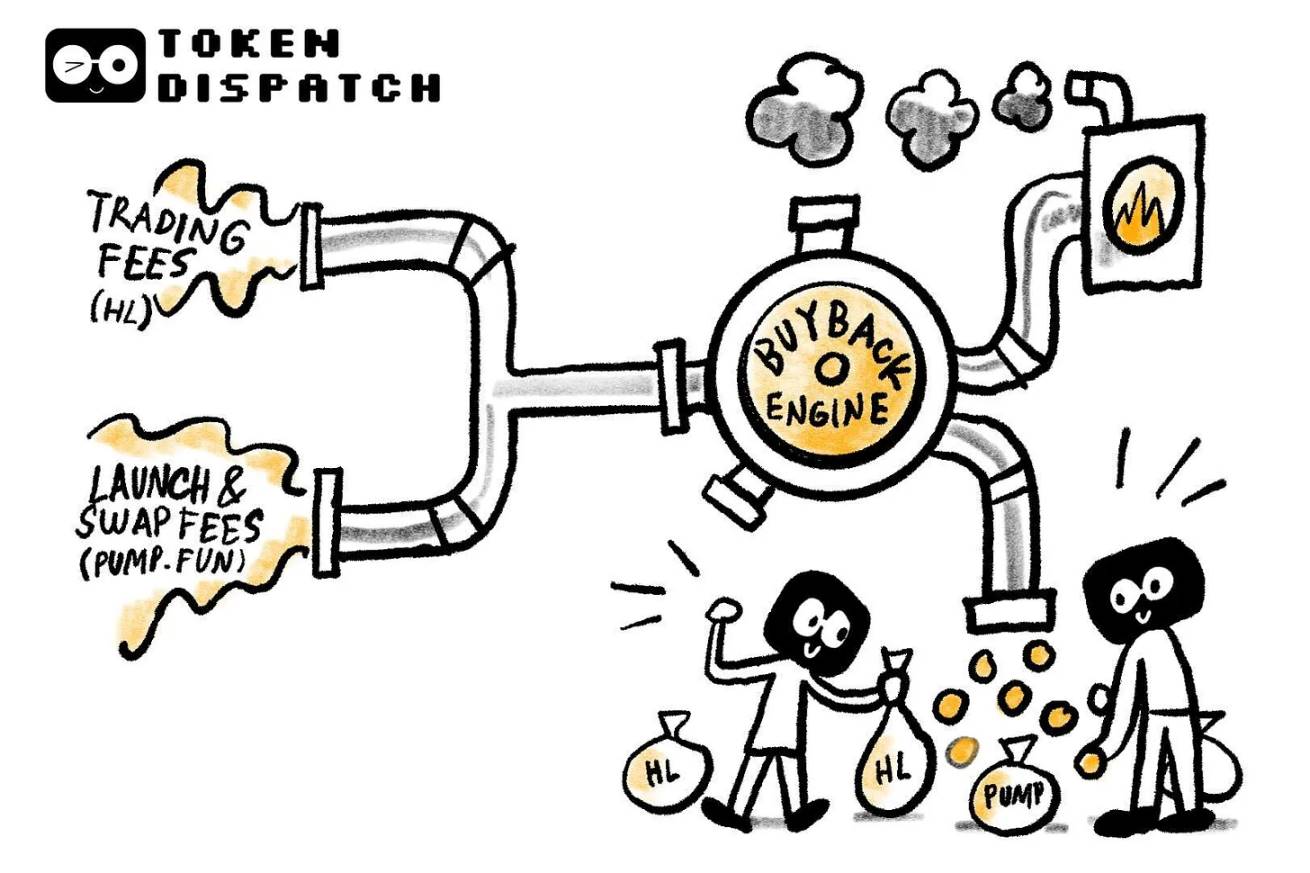

Between 2024 and 2025, Uniswap finally advanced its much-anticipated fee switch proposal—aiming to use part of the protocol’s trading fees to buy back and burn UNI tokens, attempting to transform the token from a useless governance instrument into a deflationary, income-generating asset.

However, to avoid classification as a security by the SEC, Uniswap was forced into an extremely complex structural separation, physically isolating the entity responsible for dividends from the development team. They even registered a new type of entity in Wyoming called the DUNA Decentralized Unincorporated Non-Profit Association, trying to find shelter within the narrow margins of legality.

On December 26, Uniswap’s final governance vote on activating the fee switch passed. Key components included burning 100 million UNI tokens and Uniswap Labs shutting down front-end fees to refocus on protocol-layer development.

Uniswap’s struggle and Aave’s civil war point to the same uncomfortable truth: the very thing investors crave—dividends—is precisely what regulators use as the key indicator of a security.

Want to give tokens real value? You’ll draw an SEC penalty letter. Want to avoid regulation? Then tokens must remain economically worthless.

Rights Without Recourse—Then What?

To understand the 2025 token rights crisis, we can look to more mature capital markets for insight—specifically, the American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) and Variable Interest Entity (VIE) structures used by Chinese tech firms listed overseas.

If you buy Alibaba (BABA) stock on Nasdaq, seasoned traders will tell you: you’re not purchasing direct equity in the entity operating Taobao in Hangzhou, China.

Due to legal restrictions, what you actually hold is an interest in a holding company incorporated in the Cayman Islands, which exerts control over the onshore operating entity through a series of complex contractual agreements.

That sounds a lot like some altcoins—what you’re buying is a proxy, not the thing itself.

But the lesson of 2025 shows a critical difference between ADRs and tokens: legal recourse.

While convoluted, the ADR structure rests on decades of international commercial law, robust auditing systems, and tacit understanding between Wall Street and regulators.

Crucially, ADR holders have legally enforceable residual claims. If Alibaba is acquired or taken private, acquirers must legally exchange cash or equivalent compensation for your ADRs.

By contrast, tokens—especially those once hailed as governance instruments—revealed their true nature during the 2025 acquisition wave: they appear neither on the liability nor the equity side of balance sheets.

Before the CLARITY Act took effect, this fragile arrangement survived on community consensus and bull-market faith. Developers hinted that tokens were like stocks; investors pretended they were doing venture capital.

But when the hammer of compliance fell in 2025, everyone finally faced reality: under traditional corporate law, token holders are neither creditors nor shareholders. They are more akin to fans who bought expensive membership cards.

When assets become tradable, rights can be fragmented. And when rights are fragmented, value flows toward the layer that is legally recognized, capable of carrying cash flow, and enforceable by courts.

In this sense, the crypto industry didn’t fail in 2025—it was absorbed into financial history. It began, like all mature financial markets, undergoing judgment by capital structures, legal texts, and regulatory boundaries.

As crypto’s convergence with traditional finance becomes irreversible, a sharper question emerges: where will industry value flow next?

Many assume that integration means victory. But historical experience often suggests the opposite: when a new technology is adopted by an old system, it gains scale—but rarely retains its original promise of value distribution. The old system excels at domesticating innovation into forms that are regulatable, account-friendly, and balance-sheet compatible—while firmly anchoring residual claims within existing power structures.

Crypto’s path to compliance may not return value to token holders. Instead, it’s more likely to channel value back to what the law already understands: corporations, equity, licenses, regulated accounts, and contracts that can be enforced and liquidated in court.

Token rights will persist—just as ADRs continue to exist—as tradable rights mappings permitted within financial engineering. But the real question remains: which layer of mapping did you actually buy?

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News