Blockchain is not suitable for democratic governance

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Blockchain is not suitable for democratic governance

The technology is advancing so rapidly that any blockchain project陷入 in governance wars will be left behind.

Recently, community governance issues surrounding UNI and SUSHI have sparked widespread controversy, leading many to question the practical value of decentralized governance. At this crossroads, we share an article written in 2018 by Haseeb Qureshi, managing partner at Dragonfly Capital: “Blockchains Should Not Be Democracies.” In his view, blockchains are unsuitable for democratic governance—blockchain technology evolves too rapidly, and any blockchain project mired in governance conflicts will quickly fall behind.

How should blockchains be governed? This question sounds peculiar. Theoretically, blockchains do not need management—they are permissionless, decentralized ledgers. But blockchains are more than just ledgers; they are software ecosystems and economies composed of merchants, companies, and exchanges, underpinned by communities of developers, miners, and users. Ultimately, blockchain technology must fully integrate into the messy real world. Otherwise, data on the ledger has no impact on real life. Many critical decisions must be made about how blockchains evolve. Therefore, blockchains will inevitably be governed. And their rulers will undoubtedly be humans. But the key questions remain: Who governs blockchains, and how do these individuals enforce their decisions?

Approaches to Blockchain Governance

Broadly speaking, there are two methods of blockchain governance. The first is off-chain governance. This resembles how most private institutions operate: a trusted group within the community manages the blockchain’s development and token distribution. This team is responsible for fixing bugs and security vulnerabilities, enhancing utility and scalability, representing the blockchain in public discussions, and maintaining balance among users, companies, and miners.

Superficially, this appears highly centralized and vulnerable to betrayal. If enough users disagree with governance decisions, they can initiate a hard fork and create a parallel blockchain—exactly what Bitcoin Cash and Ethereum Classic did. The threat of forking serves as a strong check against poor governance by core teams. Most mainstream blockchains—including Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, Monero, and ZCash—are managed through this model.

However, a second model is gaining momentum: so-called on-chain governance. On-chain governance aims to resolve the inherent centralization of off-chain models. In this system, users on the blockchain directly vote on proposed changes, and the blockchain automatically executes the outcome based on voting results. All decisions are handled internally via protocol rules.

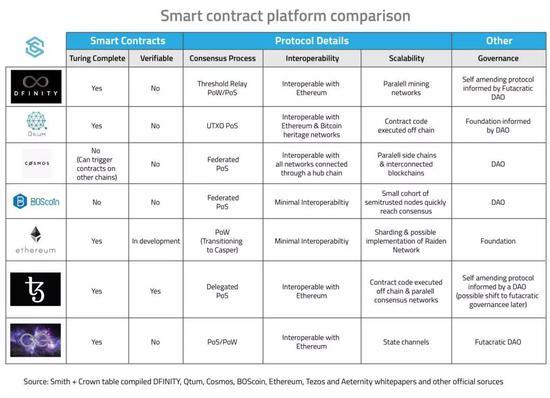

On-chain governance is central to many "Blockchain 3.0" projects such as Tezos, DFINITY, and Cosmos. Other organizations like 0x and Maker are gradually transitioning toward full on-chain governance.

On-chain governance is a radical proposition. It attempts to discard the chaotic internal structures of traditional organizations and transform blockchains into self-managing, mechanized democracies. Just as Bitcoin gives individuals sovereignty over their money, on-chain governance promises to give users control over entire financial systems. It embodies the idealism of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. As an abstract concept, it sounds grand. Yet on-chain governance is dangerous—I fear it could lead to catastrophic outcomes. Therefore, I believe democracy is ill-suited for blockchain governance.

Nobody Knows You're a Dog on the Blockchain

Democracies operate on the principle of “one person, one vote,” but blockchains are anonymous—your identity is confirmed only by your cryptographic keys. This means anyone can generate a new set of keys to create a new identity. This creates a problem: to build a democracy on a blockchain, you must solve the Sybil attack problem (where attackers subvert network reputation by creating numerous fake identities to gain disproportionate influence). Solving this requires knowing everyone’s real-world identity—something that demands a globally trusted identity verification intermediary. No such system exists today, nor is it likely to emerge soon.

Given the absence of a global identity system, on-chain governance may abandon the “one person, one vote” rule. Instead, it might adopt “one coin, one vote” via proof-of-stake, using tokens as a proxy for voting power since tokens are scarce and cannot be easily created. However, this gives greater voting weight to those holding more tokens. This is clearly not democratic—it's plutocracy. One might argue that large token holders have more at stake and thus deserve greater influence over protocol governance.

By the same logic, one could claim corporations should have greater influence over government legislation because they have more financial skin in the game. Shouldn’t businesses therefore have more legislative control? Clearly, this argument overlooks something important: granting power based on wealth enables exploitation of those with fewer resources. But are there alternatives? Should developer teams make all key decisions? Has any government ever been successfully run by a group of software engineers?

Don’t Confuse Blockchains With Nations

Setting aside concerns about plutocracy for now, let’s assume “one coin, one vote” is a valid form of democratic voting. I acknowledge democracy is a powerful system for governing nations. But blockchains are not nations, and most institutions aren’t governed democratically—corporations, militaries, nonprofits, and even open-source software projects rarely use democratic models. These examples show democracy isn't widely applied outside nation-states.

Let’s not forget: blockchains are experimental software above all else. They evolve rapidly and face numerous unresolved technical challenges. Ethereum’s roadmap alone includes transitioning consensus to proof-of-stake, completely rewriting its virtual machine, and implementing sharding—all highly complex technical endeavors. Managing such progress resembles running CERN rather than governing a country. We already have effective models for managing hardware and tech projects—think Linux kernel developers or the IETF. These are not institutions meant to be led by popular vote.

Effective technical governance should center on skilled experts who balance technical rigor with practical constraints. They should define and deliver clear technical roadmaps. In short, they should get things done.

Democracy works very differently. It emphasizes campaigning, obstructing legislation, forming political parties, and avoiding risks. In such systems, anything lacking consensus gets discarded, and enormous effort goes into persuading average voters on specific policies. Despite these inefficiencies, democracy remains the right way to govern a nation-state. But for an experimental technology, it’s absolutely the wrong model.

Moreover, we’re still in early days. I wouldn’t want my grandmother voting on blockchain protocol upgrades anytime soon. Another key difference between blockchains and nations is that you can always exit a blockchain.

Freedom, Forking, and Exit

Leaving a nation is hard. Even if you dislike your country’s governance, emigration isn’t always feasible. Governments may prevent departure, and neighboring countries may not welcome you. People don’t choose where they’re born. Hence, one argues, nations must protect citizens’ welfare because citizens can’t choose their origin.

Blockchains are different. If you dislike decisions made by your community, you can sell your tokens and move to another ecosystem. Better yet, you can support a fork—or, if capable, launch your own forked chain, just as previous groups did with Bitcoin. Forking isn’t free—but compared to international migration, it’s remarkably cheap. In an ecosystem where everyone can vote with their wallet, the benefits of democracy as a governance model remain unclear.

The Extremes of Democracy

Furthermore, democracy is extremely difficult to implement well.

Take DFINITY as an example. DFINITY aims to allow rewriting transactions via its “Blockchain Nervous System.” Imagine someone loses tokens due to theft on the DFINITY blockchain. The victim could propose invalidating the transaction. If enough validators review evidence and agree, the transaction would be reversed and funds returned. The ledger could effectively be rewritten by voter quorum. This sounds like a clever solution to common blockchain hacking problems. But upon closer inspection, DFINITY risks something worse: mob rule.

James Madison and Thomas Jefferson deeply understood the dangers embedded in democracy. In the Federalist Papers, they explicitly argued the United States should not adopt direct democracy. Instead, they advocated for a republican model with carefully designed checks and balances. History shows direct democracy often ends poorly.

As the old saying goes: “Democracy is two wolves and a sheep voting on what’s for lunch.” Generally, any 51% majority can always strip rights from the remaining 49%—this is the political analog of a 51% attack. Known as the “tyranny of the majority,” this is a well-known failure mode in democracies. What prevents this from happening on blockchains?

Altruism and inertia might reduce the likelihood, but we’ve seen precursors before. One can imagine factionalism, political persecution, and outright war between groups of varying sizes. Once conflict begins, tribalism may emerge from zero-sum political struggles.

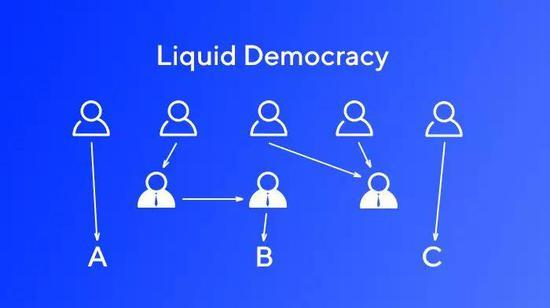

But DFINITY isn’t the only model. Many on-chain governance systems instead adopt liquid democracy, where voters can delegate their votes to representatives who vote on their behalf. These delegates may be compensated for participation.

All democracies struggle with low voter turnout (even Ethereum’s DAO Carbonvote saw only 4.5% participation). Liquid democracy cleverly addresses this by allowing token holders to delegate votes to better-informed participants. This resembles modern representative democracies and aligns in spirit with proof-of-stake. However, any delegated voting scheme brings its own issues. When representatives compete for profit-driven mandates, campaigns, bribery, propaganda, and other unpleasant political dynamics arise. Significant energy gets spent courting random delegates to align with certain factions, rather than focusing purely on protocol improvement. Why wouldn’t we expect this? When representatives are paid for voting, such behaviors are natural incentive responses. Real-world democracies are filled with complex, interlocking checks and balances for good reason. Once sufficient power is concentrated, democracy easily devolves into cronyism.

Democracy Is for Losers

Ultimately, better decision-making isn’t democracy’s primary purpose. Perhaps democracy’s greatest value lies in preserving peace amid contentious disagreements. In other words, by adhering to democratic processes, we defuse disputes that might otherwise escalate into civil war.

That’s a dramatic claim, so consider a hypothetical. Suppose two parties disagree on legislation—say, religious regulations. In a Hobbesian state of nature, opposing religious factions would go to war until one side prevails, then impose its will on the surviving minority.

Democracy avoids this. In a democratic society, both sides go to the polls. Votes are counted. The losing side might attempt rebellion, but as a minority, they’d be swiftly crushed. So they accept defeat without resistance, preserving valuable resources—including their lives. In this sense, democracy becomes an elegant, efficient institution. Voting grants legitimacy to winners and ensures defeated minorities avoid bloodshed. Thus, democracy helps protect nations from violent fragmentation.

But what happens when an internal protocol vote splits 55–45 on a blockchain? Why should the 45% accept loss and continue living under majority rule? If change is meaningful and enough participants want to go in a different direction, we should expect a protocol fork. If on-chain governance fails to prevent schisms, what value does a democratic institution really provide? What exactly is it doing for us?

Mind the Boundaries

Despite my reservations, we shouldn’t be overly harsh on on-chain governance. It’s an intriguing idea driven by genuine motivations. But ultimately, it stems from the same hubris afflicting much of the blockchain space.

In 1929, G.K. Chesterton articulated a principle now known as Chesterton’s Fence: “There exists some institution or law; let us say, for simplicity’s sake, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’ To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.’”

Not everything should be democratic—in fact, most things shouldn’t. Encountering a fence and immediately removing it is unwise. Perhaps one day blockchains will become robust and stable enough to no longer require guidance from skilled technologists. But I doubt that day is near. Technology moves too fast—any blockchain project bogged down in governance wars will be left behind.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News