Bank account frozen, cryptocurrency became my "lifeline"

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Bank account frozen, cryptocurrency became my "lifeline"

What does it feel like to suddenly lose your bank account before Christmas?

Author: Boaz Sobrado

Translation: Chopper, Foresight News

A Chase Bank branch in New York City, USA, March 25, 2021

On December 19, about four weeks after I arrived in the United States and opened a Chase Bank account, an email from the bank appeared prominently in my inbox. The message was impersonal—a standard template: "This letter is to inform you that we have decided to close your account."

The bank provided no explanation, only a list of instructions: destroy your debit card, cancel automatic payment agreements, update digital wallet information, and wait for a formal written notice. It claimed a follow-up letter would contain full details. To this day, that explanatory letter has never arrived.

My account held thousands of dollars, with recurring bills set on autopay. I had just relocated to a foreign country, and Christmas was only days away.

I wasn’t alone in facing this ordeal. In November of the same year, Jack Mallers, CEO of Bitcoin payments firm Strike, experienced a similar incident. Chase abruptly shut down both his personal and business accounts, citing only “suspicious transaction activity” as justification. More shockingly, Mallers’ father had been a private banking client at Chase for years.

Similarly, Russian lawyer Anya Chekhovich, who worked for Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, had her bank account frozen after the Russian government designated the foundation as an “extremist organization.” Although public backlash eventually forced Chase to reverse its decision, the damage had already been done. The wording of these closure notices was eerily identical.

Chase is far from alone. A preliminary investigation by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency in December revealed that between 2020 and 2023, nine major banks—Chase, Bank of America, Citibank, Wells Fargo, U.S. Bank, Capital One, PNC, TD Bank, and BMO—engaged in systemic account closures. Targeted businesses included cryptocurrency firms, arms dealers, oil and gas companies, and various political organizations.

The Trump administration has made this issue a priority. In August, Trump publicly stated that Chase and Bank of America had refused over $1 billion in his deposits, prompting him to issue an executive order directing regulators to investigate such politically influenced or potentially illegal account closures.

Most media coverage misses a crucial point: the core of this issue goes far beyond mere political or ideological conflict.

The Systemic Flaws Behind Account Closures

Payment industry veteran Patrick McKenzie offers insight in his influential essay Seeing Like a Bank. He identifies a fundamental limitation of banking systems: banks excel at tracking ledgers and verifying fund ownership and movement, but they are largely incapable of effectively monitoring anything beyond that.

The root problem lies in the underlying architecture of banking systems. Core banking processors must interface with numerous subsystems, creating multiple points of data disconnect. For example, an account closure decision might be generated in System A, archived in System B, and notification sent via System C. When you call customer service, the representative you speak to likely cannot access any of these systems.

To control costs, banks use tiered support structures. Tier 1 agents read from scripts; Tier 2 agents have slightly broader access; while Tier 3 specialists—who actually understand the reasons behind decisions—do not handle inbound calls at all. This structure is a direct result of the low-margin nature of retail banking. It allows even a high school student to open a checking account easily, but also means accounts can vanish inexplicably due to system errors.

At the same time, banks face strict regulatory requirements. They must file Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) in numerous situations—including international wire transfers or when a customer holds dual citizenship. Ironically, sometimes merely knowing that SARs exist is enough to trigger reporting.

Under U.S. federal regulation <12 CFR § 21.11 (k), if a bank has filed a SAR regarding a customer, it is legally prohibited from informing the customer about it. The law mandates silence—banks simply cannot provide explanations.

A Personal Case Study

When Chase sent me that cold, unexplained account closure notice, they may have been complying with the law—or acting on algorithmic risk assessment. What appears logically sound within the algorithm seems absurd in plain language. Holding dual citizenship, having an international background, and maintaining a modest balance—such customers are simply not worth the risk to banks. I fit this high-risk profile perfectly.

This tiered support model does have exceptions: human rights activists with large social media followings, regulators, and other VIPs can access powerful technical teams directly. Ordinary people, however, remain trapped in endless phone menu loops. I quickly stopped calling.

For me, being locked out of my account for weeks was a manageable inconvenience. But for those already living paycheck to paycheck, it’s an inescapable nightmare. Banks serve the general public because society demands it. Yet the high cost of universal coverage has produced a system deeply hostile to “atypical” customers. And when financial inclusion becomes the norm, the number of such “atypical” individuals is far greater than one might expect.

Cryptocurrency: An Alternative to the Banking System?

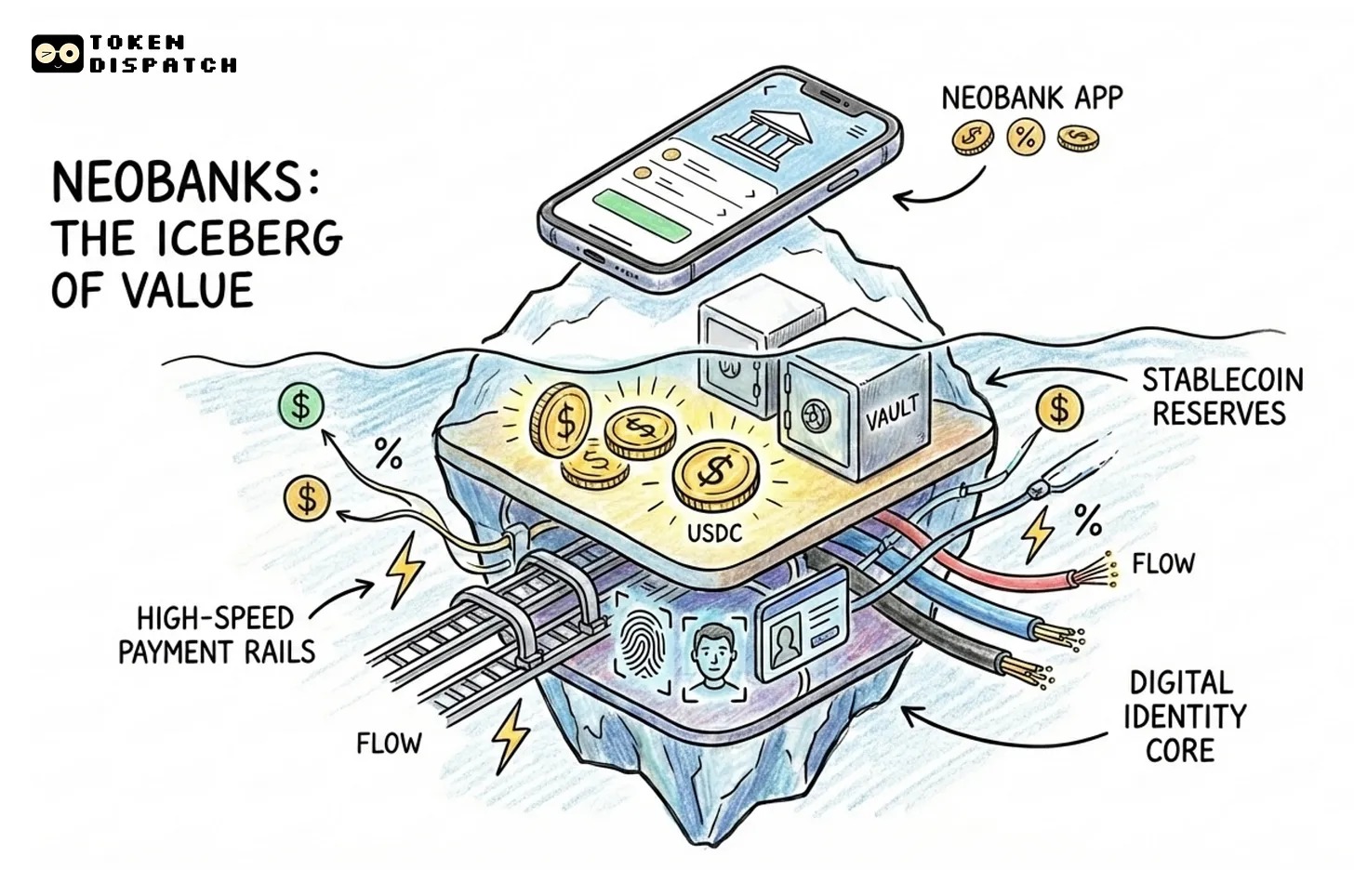

When I received that account closure email on December 19, what came to mind wasn’t Federal Reserve policy or debates about decentralization—but the tangible advantages of cryptocurrency. I hold several thousand dollars’ worth of stablecoins (USDC) in a self-custodied wallet—funds I can access anytime, without navigating phone menus, waiting for checks, or worrying about when I’ll regain access to my money.

For immigrants, foreigners, and globally mobile professionals—people whose lives span borders—traditional banks view identity complexity as risk. International backgrounds mean multiple compliance checks, multiple red flags, and algorithms concluding: “Too much trouble—decline.”

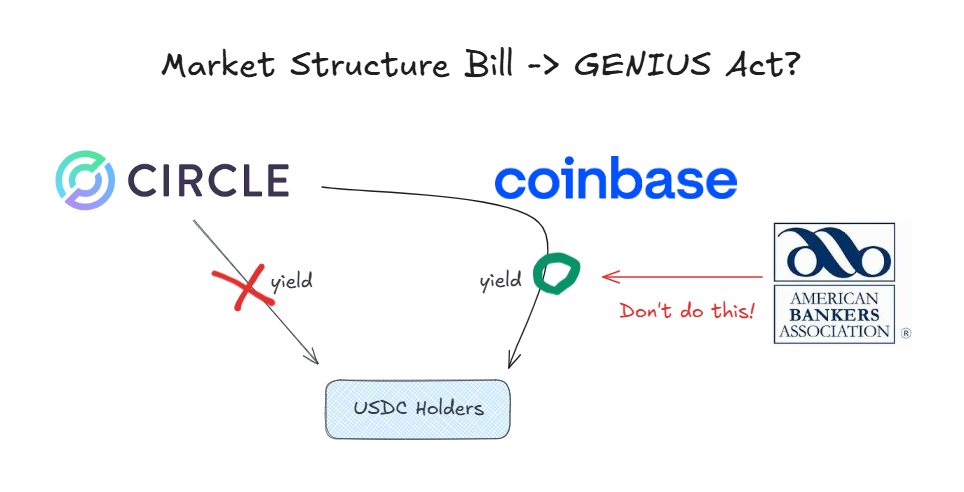

Stablecoins were designed precisely to serve these users—offering dollar-denominated value that moves freely across borders. These very traits that traditional banks see as “risk signals” make stablecoins an ideal solution for such needs.

The Trump administration’s focus on “illegal account closures” may inadvertently accelerate cryptocurrency adoption. When high-profile crypto executives like Mallers face account closures, the issue gains visibility. But the real driver of mass crypto adoption isn’t politics—it’s the terrible experience ordinary people have with traditional banking.

I’m still waiting for Chase’s explanatory letter, hoping it will clarify what happened. But chances are, it will mirror the vague email—citing corporate policies and procedural clauses that sound reasonable on paper but feel arbitrary and unjust when applied to an individual.

Banks aren’t malicious—they’re simply outdated institutions, trying to manage complex financial ecosystems with obsolete systems. These systems generate false risk alerts—and sometimes, that alert lands on someone’s desk right before Christmas.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News