Chen Yizhou, who ran Renren into bankruptcy, has now backed the first U.S. crypto bank

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Chen Yizhou, who ran Renren into bankruptcy, has now backed the first U.S. crypto bank

First become a bank, then use the identity of a bank to do things others cannot.

Author: Sleepy.txt

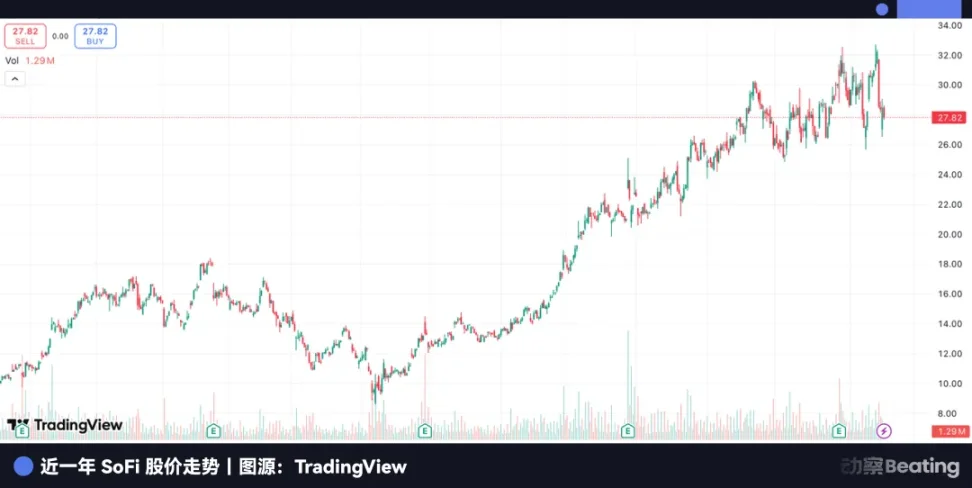

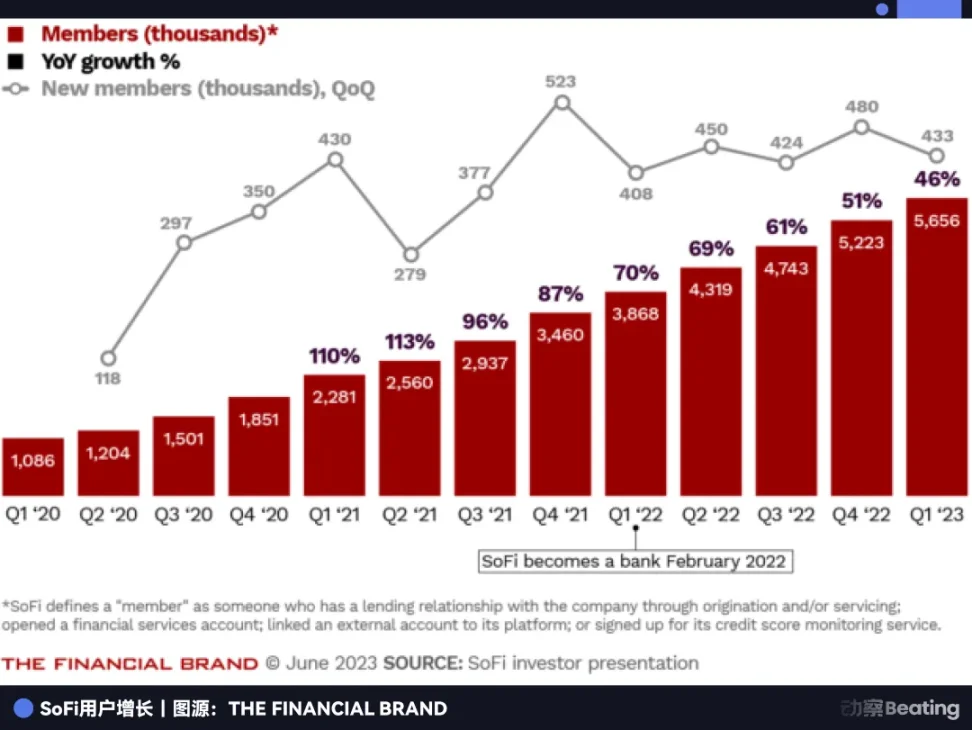

In November, U.S. fintech giant SoFi announced the full opening of cryptocurrency trading to all retail customers. This came just three years after obtaining a national banking charter, making it the first true "crypto bank" in the United States—and it’s even preparing to launch a U.S. dollar stablecoin by 2026.

On the day of the announcement, SoFi's stock price surged to an all-time high, reaching a market capitalization of $38.9 billion, with a year-to-date gain of 116%.

Chen Yizhou, CEO of Xiaonei (later renamed Renren), was one of SoFi’s earliest investors. In 2011, introduced at Stanford University, he met SoFi’s founders and within less than five minutes decided to invest $4 million.

Later, recalling this investment in a speech, he said: "At the time, I didn’t even know what P2P lending was. I just thought, this thing is good."

The most traditional financial license and the most sensitive crypto business have been fused into one narrative by SoFi. Before SoFi, Wall Street’s traditional banks wouldn’t touch cryptocurrencies, while crypto giants like Coinbase couldn’t obtain banking licenses. SoFi became the only outlier standing precisely at this intersection.

But if we rewind the timeline, we’ll find its origin wasn’t glamorous—not a tech company, not a crypto startup, but rooted in the most conventional “peer-to-peer lending,” just like China’s generation of P2P platforms. Yet over the past decade, they’ve taken completely divergent paths.

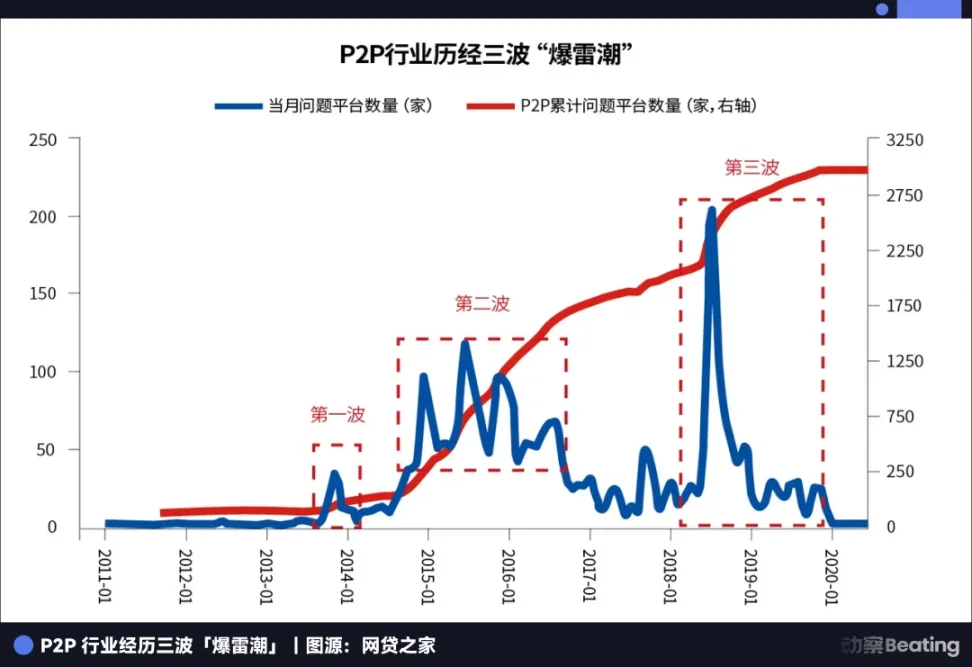

Across the Pacific, China’s P2P industry has become history—falling from over 5,000 platforms at its peak to zero survivors. A bubble of an era finally burst, leaving behind hundreds of billions in bad debt and countless shattered families.

Both started with P2P—why did one head toward death, while the other achieved rebirth, evolving into a new species called the “crypto bank”?

Two Genes of P2P

Because their underlying DNA is entirely different.

The Chinese P2P model was essentially a business of “traffic + high-interest loans,” acquiring customers through offline canvassing and online channels, charging high interest rates with short cycles. Platforms didn’t care about long-term credit or customer relationships.

SoFi, on the other hand, was a completely different creature. In 2011, as Chinese P2P platforms sprouted like mushrooms, SoFi was born in a classroom at Stanford Graduate School of Business. Four MBA students pooled $2 million from alumni and made their first move: lending $50,000 each to 40 classmates for tuition.

SoFi’s initial story couldn’t have been more humble—solving real borrowing needs on campus, serving their very first clients: fellow students. This allowed SoFi to bypass the hardest challenge from the start: risk control.

It targeted America’s most creditworthy group—elite university students. With promising future incomes and extremely low default rates, these borrowers were ideal. More importantly, SoFi stands for “Social Finance,” and its earliest lending relationships stemmed from alumni networks. Borrowing from schoolmates was essentially leveraging trust among acquaintances—the alumni identity itself served as the most natural guarantee.

Unlike Chinese P2P platforms charging annualized interest rates in the twenties or higher, SoFi priced its rates lower than both government and private lenders from day one. It didn’t chase high spreads; instead, it aimed to attract top young talent into its ecosystem, building a long-term business that could last ten or twenty years. Student loans were merely the starting point—followed by mortgages, investments, insurance, and the entire financial life cycle.

Chinese P2P was transactional—hit-and-run deals; SoFi was service-oriented—steady and enduring.

And during that phase, a wave of investors willing to bet on “atypical finance” began to emerge.

Chen Yizhou, who built Xiaonei, invested in this “campus loan” startup.

This well-placed bet helped him avoid the pitfalls of high interest rates and pooled funds that later plagued China’s P2P sector, allowing him to back a financial services firm with an elite club vibe.

This investment also inspired another Chinese investor. Zhou Yahui, founder of昆仑万维 (Kunlun Tech), deeply influenced by Chen’s move into SoFi, decided to invest in China’s Qufenqi. Zhou later called Chen his “mentor.” But Qufenqi took a different path—entering the campus loan market with high interest rates, eventually mired in controversy and regulatory crackdowns.

Three years after Chen invested in SoFi, in Q4 2014, Renren launched its own campus loan product, “Renren Fenqi.” This time, Chen was no longer the “clueless P2P investor,” but a shrewd operator. Renren Fenqi offered installment loans to students, collecting fees and interest, while launching “Renren Licai” as a P2P wealth management platform.

From then on, China’s P2P industry floored the accelerator. Campus loans were just the entry point, quickly expanding into cash loans, consumer loans, and packaged asset wealth products. High interest rates, fund pooling, and rigid redemption promises became standard practice. Renren Fenqi quietly exited student consumer lending in May 2016, shifting focus to auto dealer installment loans—an early retreat before the industry spiraled out of control.

2018 was the make-or-break turning point.

China’s P2P sector had raced ahead amid regulatory gaps and inflated interest rates, culminating in mass defaults that year—platforms shut down, assets vanished, leading swiftly to complete liquidation. By November 2020, China’s P2P platforms were fully wound down, marking the total collapse of the industry.

As the industry collapsed, the man who first backed SoFi was also closing the chapter on that investment. Chen Yizhou transferred Renren’s stake in SoFi through a series of internal transactions to a company under his control, then sold it at a low price to buyers including SoftBank. Minority shareholders erupted in fury, New York courts intervened, and litigation dragged on for years.

To many, this meant SoFi was merely a disposable chip, a footnote to the end of the P2P era. But at the same time, SoFi’s management was solving a different puzzle—transforming from a “regulated entity” into “part of the regulatory system.”

While everyone assumed FinTech’s destiny was to disrupt banks, SoFi, as a FinTech company, went the opposite way—it chose to become a bank.

Life-or-Death Decision: From P2P to Bank

In July 2020, while the entire FinTech world was buzzing about decentralization, cryptocurrency, and disrupting banks, SoFi made a decision that surprised everyone—it formally applied to the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) for a national banking charter.

At the time, this felt like moving backward in history. A star company branded with technological innovation was turning to embrace the most traditional, heavily regulated, and least “cool” identity possible.

Yet in business history, there are always moments when, as everyone rushes in one direction, the one who turns back either misjudges—or sees further.

Why did SoFi do this? In truth, from its very first loan, this company behaved more like a bank than a matching platform. It valued long-term relationships, risk control, and the lifetime value of customers—not just one-off interest spreads.

More crucially, a banking license means far more than just “compliance.” On the surface, it allows accepting public deposits, issuing various loans, and enjoying Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) protection. But the real power lies in drastically lowering funding costs.

Funding cost has always been the Achilles’ heel of FinTech companies.

Prior to obtaining a banking license, SoFi relied on external financing and bond issuance—costly and unstable. With the license, however, it could absorb large-scale savings deposits like any traditional bank. These funds typically cost only 1–3%, compared to 5–8% or higher in capital markets.

In finance, where scale magnifies everything, this seemingly small cost difference becomes enormous—determining profitability and growth speed.

SoFi’s decision was essentially a strategic trade: embracing regulation in exchange for access to the banking system’s lifeblood—a funding pool with near-minimal costs.

Finance is ultimately a game of money—whoever accesses more funds at lower cost gains ultimate pricing power.

After a grueling year and a half of review, on January 18, 2022, the OCC and the Federal Reserve finally approved. SoFi became the first major U.S. fintech company in history to obtain a full banking charter.

SoFi earned this rare license because, over ten years, it proved to regulators it wasn’t a “barbarian.” Its business model was sound, its risk controls exemplary. To regulators, it was a “trustworthy innovator.” Neither aggressive crypto firms nor sluggish traditional banks could replicate SoFi’s path.

But this victory came at a price.

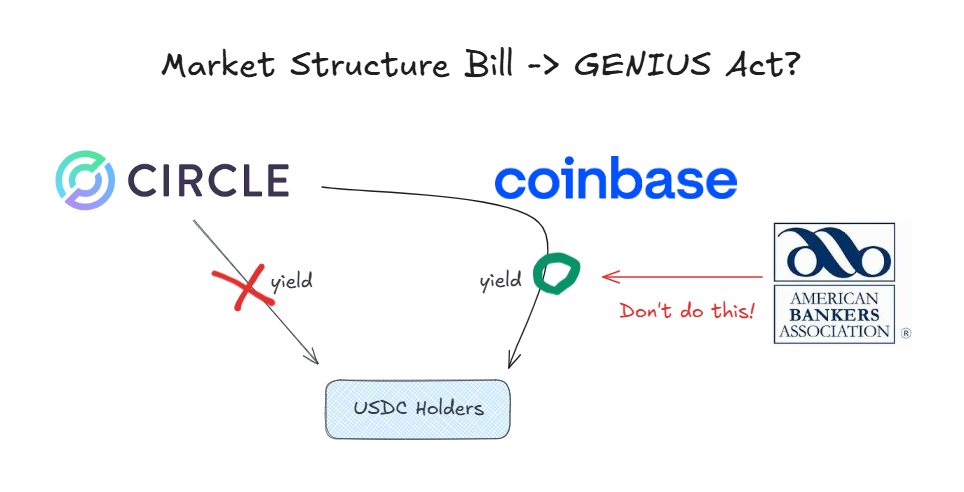

A regulatory filing in September that year made it clear: after obtaining the license, SoFi could not offer any cryptocurrency-related services without separate approval. In other words, SoFi had to abandon the red-hot crypto business. To regulators, a real bank must prioritize stability—can’t have both the license and the hype.

By complying and pausing operations, SoFi sent a clear signal: it was willing to bind itself by banking standards.

Recall that prior to this, SoFi had already launched crypto trading in early 2020, allowing users to buy and sell Bitcoin, Ethereum, and other major cryptos on its platform. Though small in scale, this represented SoFi’s first step into emerging finance.

Then came 2021—the golden age of crypto. Bitcoin soared from $29,000 to a yearly high of $69,000. That year, rivals like Coinbase and Robinhood raked in massive profits from crypto trading. Meanwhile, SoFi laid down its arms just before dawn.

What was Chen Yizhou doing during this critical period when SoFi was sacrificing short-term gains for long-term positioning?

In October 2021, amid allegations of “asset stripping,” a New York court seized $560 million in assets held by his private company OPI. Under immense pressure, he eventually settled with minority shareholders, paying at least $300 million in compensation.

One side: a company betting on the future, trading short-term flashiness for long-term space. The other: the original backer settling old debts and forced to exit.

The Birth of the Crypto Bank

SoFi chose the unglamorous, harder, but more sustainable path: first become a regulator-approved bank, then innovate. This strategic patience is what sets it apart from most FinTech firms.

So where was it truly headed?

After securing the banking license, SoFi’s business model underwent a fundamental transformation. The most direct change: explosive growth in deposit volume.

Offering interest rates significantly above market averages, SoFi attracted a flood of users. This steady stream of low-cost deposits provided ample fuel for its lending operations.

Financial reports clearly show this shift: deposits jumped from $1.2 billion in Q1 2022 to $21.6 billion by end-2024—an 18-fold increase in two years. From a large-scale wealth platform, it evolved into a mid-sized national bank. By Q3 2025, the company’s net revenue reached $962 million, up nearly 38% year-on-year.

The lowest cost is the highest moat. While other FinTech companies still struggled with expensive funding, SoFi now possessed a “money printer” on par with traditional banks. In just two years, it completed the leap from platform to bank, leaving all competitors far behind.

What truly reshaped the industry was the authority granted by the license. Without it, crypto was merely an add-on for FinTech; with it, the same service entered the banking system as a formal, compliant offering. These are two entirely different levels of legitimacy.

On November 11, 2025, SoFi dropped a bombshell—after a three-year pause, it announced the reopening of cryptocurrency trading to retail customers.

This made SoFi the first and only financial institution in U.S. history to hold a national banking charter while offering mainstream crypto trading.

SoFi was effectively creating a new financial species—one combining the stability and low-cost funding of traditional banks with the agility and visionary potential of FinTech and crypto. For users, it resembled a “one-stop financial supermarket,” where savings, loans, stock trading, and crypto investing could all be done within a single app.

Its innovation wasn’t inventing something new, but integrating two seemingly opposing systems—banking and crypto—into a coherent whole. Wall Street analysts spared no praise, calling SoFi’s current form the closest realization of FinTech’s ultimate potential.

Looking back, SoFi’s 2022 decision to temporarily abandon crypto was actually a masterstroke of strategic retreat. It sacrificed short-term growth to secure the industry’s scarcest advantage. When it returned to the table in 2025, it faced no equals.

Against Consensus

Traditional Wall Street banks suffer from stagnant stock prices, with P/E ratios lingering between 10 and 15. SoFi, however, commands a P/E ratio of 56.69—valued not as a bank, but as a tech company.

This is SoFi’s greatest achievement: being a bank, yet refusing to live like one.

For the past fifteen years, FinTech’s grand narrative has been about using technology to disrupt traditional banks. Coinbase promised universal crypto access; Robinhood championed commission-free trading revolution; Stripe aimed to perfect seamless payments.

SoFi tells a completely different story: we will first become a bank, then use that status to do what others cannot.

The 2022 “compromise” and “surrender” now appear, three years later, as the boldest innovation of all.

Today, SoFi’s story has reached its climax—but is far from over. Now the sole “crypto bank,” what’s its next battlefield? Expanding lending scale? Deepening crypto offerings? Or leveraging this unique identity to unlock possibilities we can’t yet foresee?

This company began with P2P, squeezed forward through regulatory cracks, and now stands in a position no one in the industry ever imagined.

No one would have linked SoFi with the term “crypto bank” at the start. In 2025, no one can predict its next fifteen years.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News