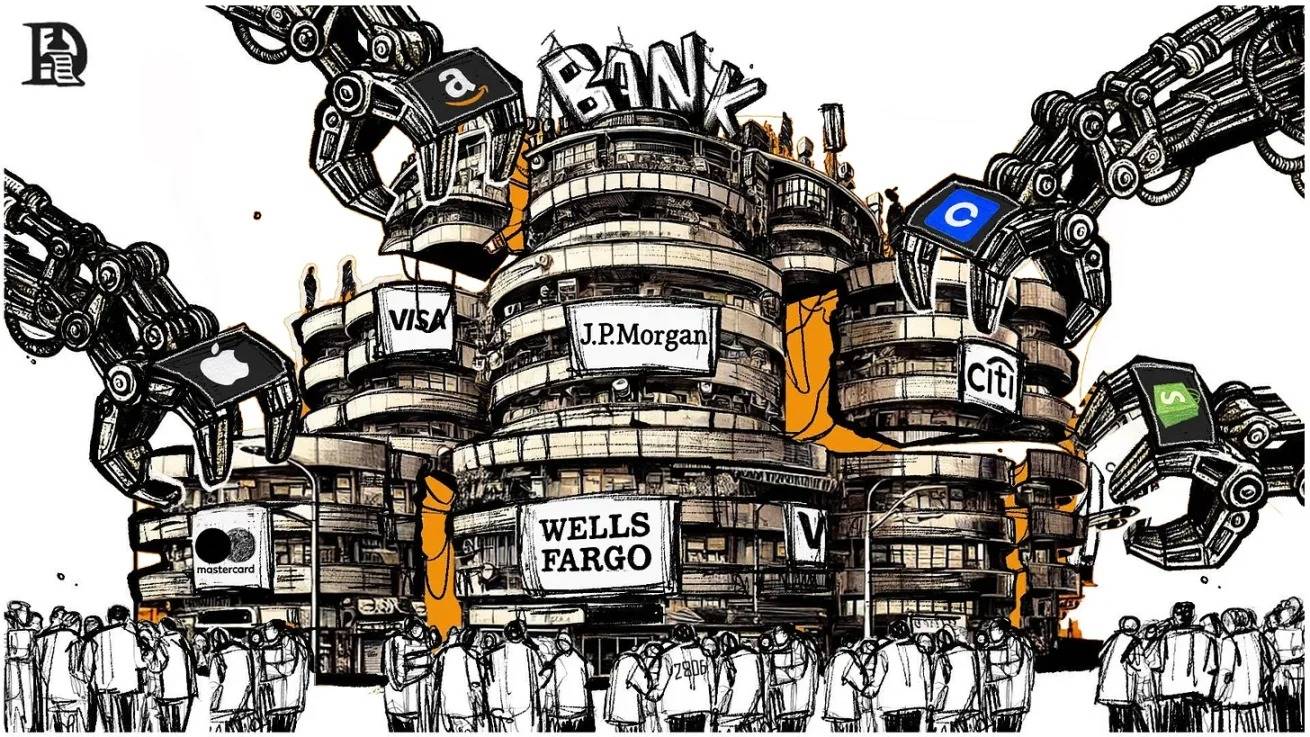

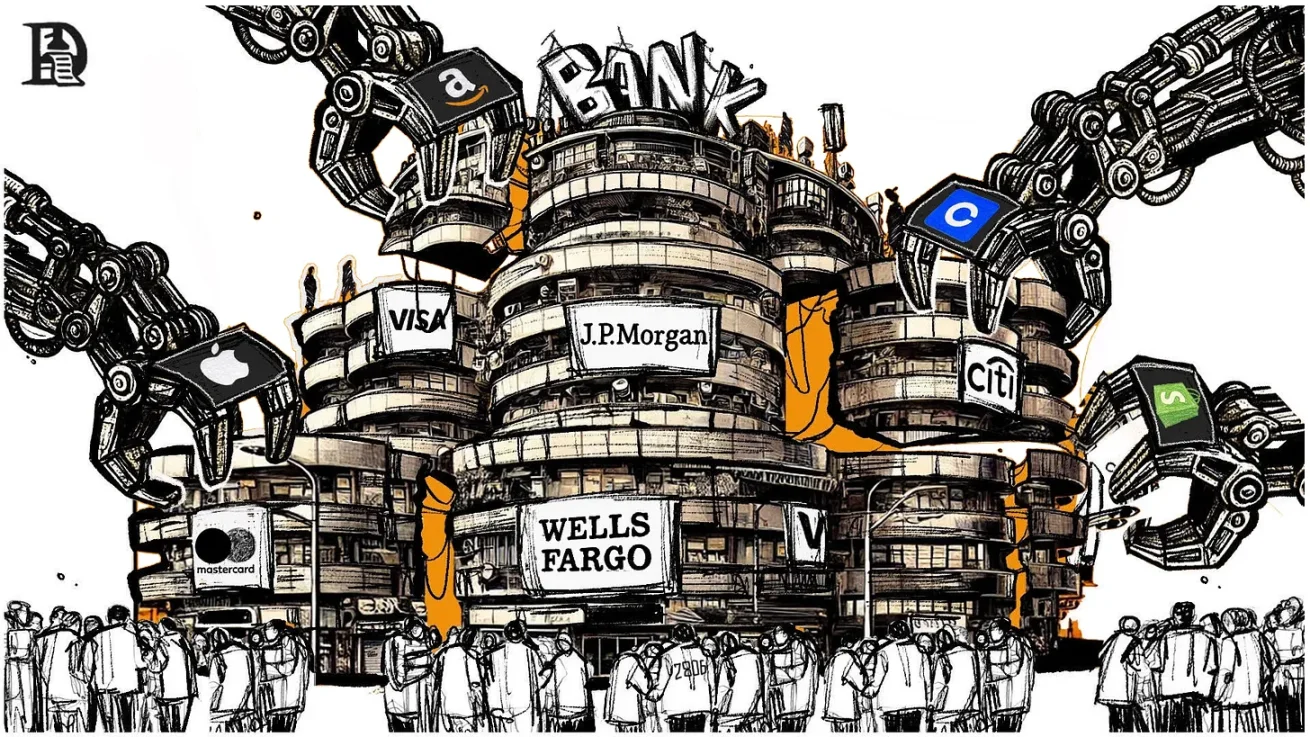

What would a future where everything can be a bank look like?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

What would a future where everything can be a bank look like?

When everything is a bank, nothing is a bank.

Author: oel John, Sumanth Neppalli, Decentralised.co

Translation: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

Cryptocurrency has now become genuine financial technology.

This article explores how legislative changes will disintermediate traditional banks. If blockchains are the rails for money and everything becomes a market, users will ultimately leave their idle deposits on their preferred applications. In turn, this will cause balances to accumulate within apps that have massive distribution power.

In the future, everything can be a bank—but how will that happen?

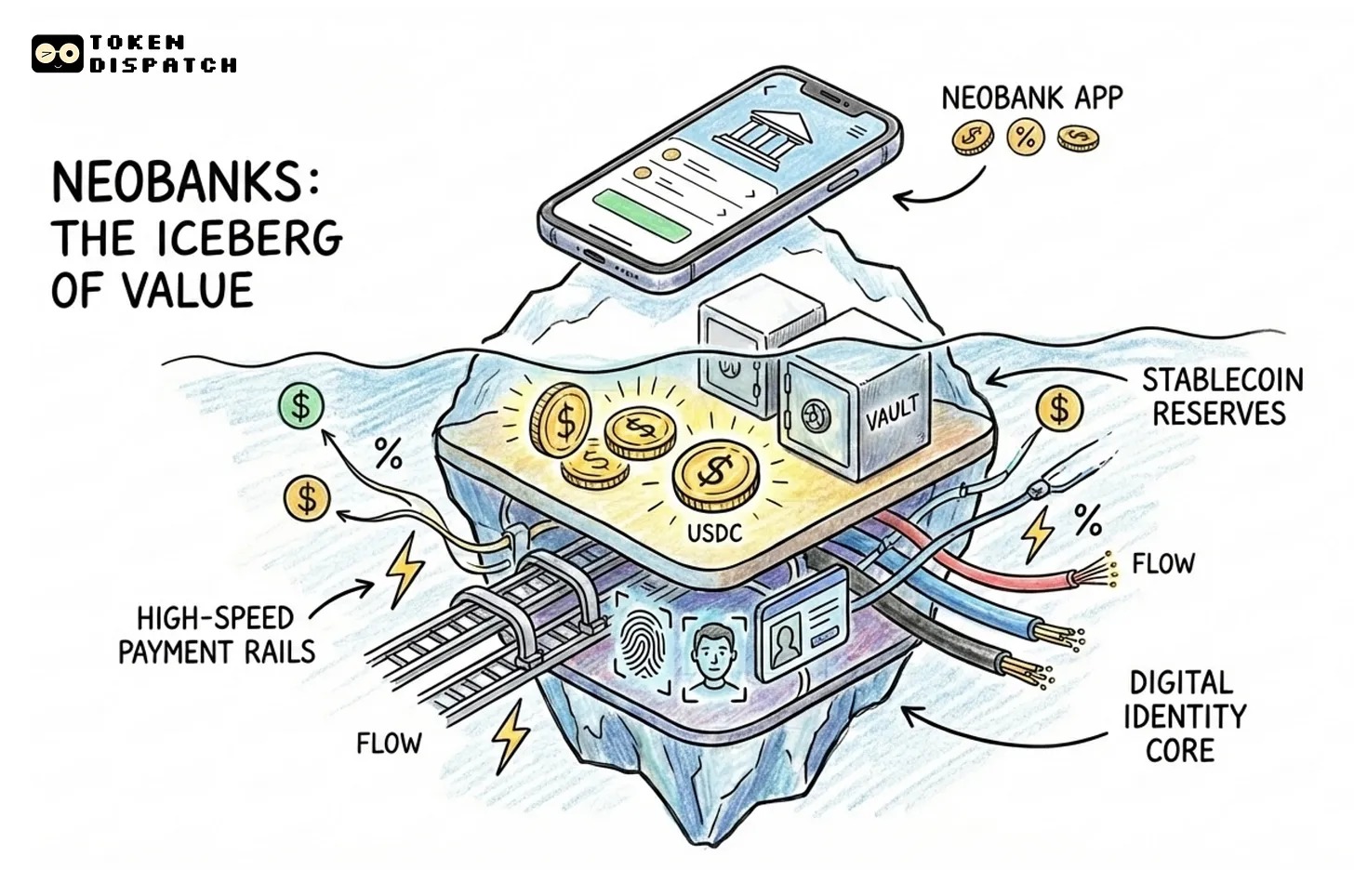

The GENIUS Act allows applications to hold U.S. dollars on behalf of users in the form of stablecoins. It flips the incentive switch for platforms, encouraging users to deposit funds and spend directly through the app. But banks are more than just vaults storing U.S. dollars; they are complex databases layered with logic and compliance. In today’s discussion, we explore how the tech stack enabling this transformation is evolving.

Most fintech platforms we use are essentially wrappers around the same set of underlying banks. So instead of chasing the next shiny payment product, we begin building direct relationships with the banks themselves.

You can’t build a startup on top of another startup. You need direct relationships with entities that actually do the work, so if something goes wrong, you’re not stuck playing telephone across layers of intermediaries. As a founder, choosing a stable but slightly old-fashioned vendor can save you hundreds of hours—and just as many back-and-forth emails.

In banking, most profits are made where the money sits. Traditional banks hold billions in user deposits and may have internal compliance teams. Compared to a startup founder worrying about their license, a bank might be the safer choice.

Yet at the same time, enormous profits can also be earned by sitting in the middle layer where assets change hands frequently. Robinhood doesn't "hold" stock certificates, and most crypto trading terminals don't custody user assets. Yet they generate billions in fees annually.

These are two contrasting forces in finance—the tug-of-war between wanting custody rights and becoming the layer where transactions occur. Your traditional bank might see a conflict in letting you trade meme coins using assets it custodies because it earns money from deposits. Meanwhile, exchanges profit by convincing you that wealth is generated by betting on the next meme token.

Behind this friction lies an evolving concept of portfolios. By contrast, a savvy 27-year-old today might view her holdings in Ethereum, rights to Sabrina Carpenter's music, and streaming royalties from *My Oxford Year* as secure additions to her portfolio alongside gold and stock certificates. While rights and streaming royalties aren't tangible today, evolving smart contracts and regulations could very well make them possible within the next decade.

If the definition of a portfolio is changing, then where we store our wealth will also change. Few places illustrate this shift as clearly as today’s banks. Banks capture 97% of all banking revenue, leaving fintech platforms with only about 3%. This is classic Matthew effect—banks generate most of the income because most capital currently resides with them. But could businesses be built by peeling off parts of this monopoly and owning specific functions?

We tend to think yes. That’s partly why half of our portfolio consists of fintech startups.

Today’s article aims to argue for the disintegration of banks.

The new banks aren’t in gleaming downtown offices—they’re in your social feeds and inside your apps. Cryptocurrency has reached a stage of maturity where it no longer concerns only early adopters. It’s beginning to flirt with the boundaries of fintech, allowing us to build things targeting the entire world as the total addressable market (TAM). What does this mean for investors, operators, and founders?

We attempt to find answers in today’s topic.

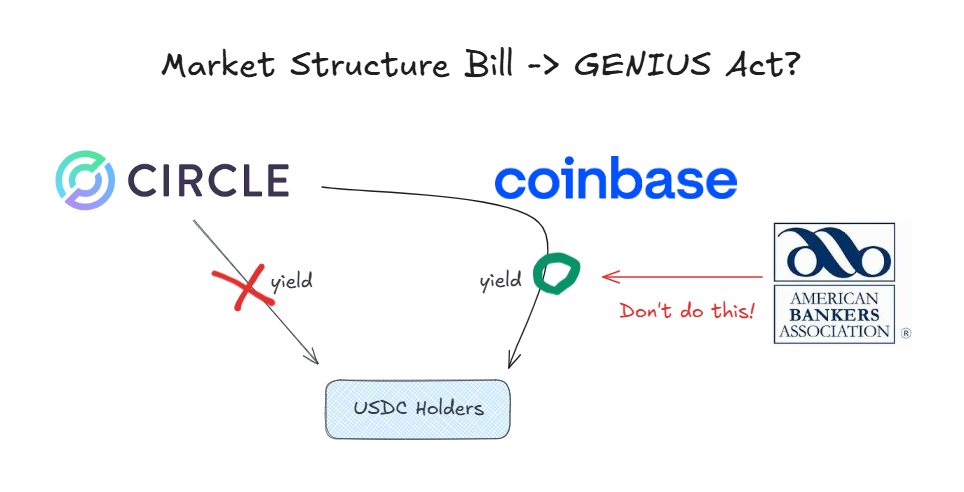

Liquidity and the GENIUS Act

Warren Buffett is called the Oracle of Omaha for good reason—his investment performance seems almost magical. But behind that magic lies some often-overlooked financial engineering. Berkshire Hathaway possesses what can be seen as permanent capital. In 1967, he acquired an insurance business with steady idle capital. In insurance terms, he could leverage “float”—premiums collected but not yet paid out in claims—which acts like an interest-free loan.

Contrast this with most fintech lending platforms. LendingClub is a startup focused on peer-to-peer lending. In this model, liquidity comes from other users on the platform. If I lend money to Saurabh and Sumanth on LendingClub and neither repays, I’m less likely to lend to Siddharth on the same platform. By then, my trust in the platform’s ability to vet, verify, and onboard quality borrowers has weakened.

If every Uber ride ended in an accident, would you keep using Uber?

Think of the same dynamic, but applied to lending. LendingClub eventually had to acquire Radius Bank for $185 million to gain access to a stable source of deposits that could fund loans.

Likewise, SoFi spent nearly $1 billion over seven years to scale as a non-bank lender. Without a banking charter, you’re not allowed to take deposits and lend them to borrowers. So it had to rely on partner banks to supply loan capital, which ate up most of the interest generated. Imagine borrowing from Saurabh at 5% and lending to Sumanth at 6%—that 1% spread is your profit. But if you had a stable deposit base like a bank, you could earn much more.

That’s exactly what SoFi eventually did. In 2022, it acquired Golden Pacific Bank in Sacramento for $22.3 million to obtain a charter allowing it to accept deposits. This move pushed its net interest margin to around 6%, far above the typical 3–4% at traditional U.S. banks.

Smaller bank wrappers can’t generate large enough margins to operate. What about giants like Google? Google launched Plex as a way to embed wallets directly into your Gmail app. It was built in partnership with a banking consortium to handle deposits, involving Citigroup and Stanford Federal Credit Union—but it never launched. After two years of regulatory back-and-forth, Google canceled the project in 2021. In other words, you can own the world’s largest inbox, yet struggle to convince regulators why people should transfer money where they send emails. Such is life.

Venture capital understands this struggle. Since 2021, total funding flowing into fintech startups has halved. Historically, much of a fintech startup’s moat was regulatory. That’s why banks capture the largest share of banking revenue. But when banks misprice risk, they gamble with depositors’ money—as we saw with Silicon Valley Bank.

The GENIUS Act erodes that moat. It allows non-banks to hold user deposits in the form of stablecoins, issue digital dollars, and settle payments 24/7. Lending remains siloed, but custody, compliance, and liquidity are gradually shifting into the realm of code. We may be entering a new era where a new generation of Stripes builds atop these financial primitives.

But does this increase risk? Are we allowing startups to gamble with user deposits—or only letting suited professionals do so? Not quite. Digital dollars or stablecoins are often far more transparent than their traditional counterparts. In the traditional world, risk assessment is private. On-chain, it’s publicly verifiable. We’ve already seen versions of this when ETF or DAT holdings can be verified on-chain—you can even verify how much Bitcoin countries like El Salvador or Bhutan hold.

The shift we’ll witness is that products may look like Web2, but assets will run on Web3 rails.

If blockchain rails enable faster money movement, and digital primitives like stablecoins allow anyone to hold deposits under proper regulation, we’ll see a new generation of banks emerge with entirely different unit economics.

But to understand this shift, it helps first to understand the components that make up a bank.

Building Blocks of a Bank

What exactly is a bank? At its core, it does four things:

First, it holds information about who owns what assets—a database.

Second, it enables people to transfer funds between each other via transfers and payments.

Third, it ensures compliance with users to confirm that the assets held are legitimate.

Fourth, it uses the data in the database to upsell loans, insurance, and trading products.

Cryptocurrency eats away at these pieces in reverse order. Stablecoins, for example, aren’t mature banks today, but they already command huge transaction volume. Visa and Mastercard historically charged tolls on everyday transactions. Every swipe funneled basis points into their moat because merchants had no alternative.

By 2011, average U.S. debit card interchange fees were around 44 basis points—high enough for Congress to pass the Durbin Amendment, cutting those rates in half. Europe set even lower caps in 2015—0.20% for debit, 0.30% for credit—after Brussels ruled the two giants were “coordinating rather than competing.” Yet uncapped U.S. credit cards still settle at 2.1%–2.4% today, only slightly lower than a decade ago.

Stablecoins overturn this economic model. On Solana or Base, settling a USDC transfer costs less than $0.20, a fixed fee regardless of amount. A Shopify merchant accepting USDC via self-custody wallets keeps the 2% network fee previously taken by credit card networks. Stripe already sees the writing on the wall—it now quotes 1.5% for USDC checkout, below its standard 2.9% + $0.30 rate.

New ways money flows in the U.S.

These rails invite new participants at much lower cost. YC-backed Slash lets any exporter start accepting payments from U.S. customers in five minutes—no Delaware C-corp, no acquiring bank contract, no paperwork, no lawyer fees—just a wallet. The message to legacy processors is clear: upgrade to stablecoins or lose swipe revenue.

For users, the economic case is straightforward.

Accepting stablecoins in emerging markets avoids FX hassles and outrageous fees.

It’s also the fastest way to send cross-border funds, especially for businesses with downstream import payments.

You save the ~2% fee paid to Visa and Mastercard. There are off-ramping costs, but in most emerging markets, stablecoins trade at a premium to the dollar. USDT trades at 88.43 rupees in India, while Transferwise offers dollars at 87.51 rupees.

The reason stablecoins are accepted in emerging markets is simple: the economics are compelling. They’re cheaper, faster, and safer. In regions like Bolivia with 25% inflation, stablecoins offer a viable alternative to government-issued currency. Essentially, stablecoins let the world taste what blockchain as financial rails might look like. The natural evolution is exploring what other financial primitives these rails can support.

A merchant converting cash to stablecoins quickly realizes the challenge isn’t receiving funds—it’s operating a business on-chain. Funds still need vaults, yesterday’s sales must be reconciled, suppliers expect payments, payroll needs streaming, auditors demand proof.

Banks bundle all this into core banking systems—monolithic relics from the mainframe era, written in Cobol, maintaining ledgers, enforcing cutoffs, and pushing batch files.

Core banking software (CBS) performs two basic functions:

-

Maintaining a tamper-proof ledger of truth: who owns what, mapping accounts to customers.

-

Securely exposing that ledger to the outside world: supporting payments, loans, cards, reporting, risk management.

Banks outsource this work to CBS providers. These are tech companies skilled in software, while banks specialize in finance. This architecture dates to the computerization of the 1970s, when branches moved from paper ledgers to connected data centers—and then ossified under mountains of regulation.

The FFIEC is an agency that issues operational guidelines for all U.S. banks. It outlines rules for core banking software: primary and backup data centers in separate geographic regions, redundant telecom and power lines, continuous transaction logging, and constant monitoring for security incidents.

Replacing a core banking system is a high-stakes event because data—every customer balance and transaction—is locked in the vendor’s database. Migration means weekend cutover, dual-ledger runs, fire drills with regulators, and a high chance of failure the next morning. This built-in stickiness turned core banking into near-permanent leases. The top three vendors—Fidelity Information Services (FIS), Fiserv, and Jack Henry—all trace back to the 1970s and still lock banks into roughly seventeen-year contracts. Together, they serve over 70% of banks and nearly half of credit unions.

Pricing is usage-based: a retail checking account costs $3–$8 per month, decreasing with volume but increasing with add-ons like mobile banking. Turn on fraud tools, FedNow payment rails, analytics dashboards, and fees climb higher.

Fiserv alone earned $20 billion from banks in 2024—about ten times the fees generated on the Ethereum chain during the same period.

When assets sit on public blockchains, the data layer is no longer proprietary. USDC balances, tokenized Treasuries, loan NFTs—all reside on the same open ledger readable by any system. If a consumer app finds its current “core layer” too slow or expensive, it doesn’t need to migrate byte states; it simply points a new orchestration engine to the same wallet addresses and keeps running.

That said, switching costs don’t drop to zero—they just mutate. Payroll providers, ERP systems, analytics dashboards, and audit pipelines all need to integrate with the new core. Switching vendors means reconnecting these hooks, not unlike changing cloud providers. Core isn’t just a ledger—it runs business logic: mapping user accounts, cutoffs, approval workflows, exception handling. Even if balances are portable, re-encoding these logics in a new tech stack requires effort.

The difference is that these frictions are now software problems, not data hostage situations. There’s still glue work in coding workflows, but those are sprint-cycle issues, not multi-year hostage negotiations. Developers can even adopt multi-core strategies—one engine for retail wallets, another for treasury operations—since both point to the same authoritative blockchain state. If one vendor fails, they fail over by redeploying containers, not by scheduling data migrations.

Viewed through this lens, the future of banking looks very different. These components exist in isolation today, waiting for developers to bundle them for retail users.

Fireblocks secures over $10 trillion in token flows for banks like BNY Mellon. Its policy engine can mint, route, stake, and reconcile stablecoins across 80+ chains.

Safe secures around $100 billion in smart account treasuries; its SDK offers any app simple login, multisig policies, gas abstraction, streaming payroll, and auto-rebalancing.

Anchorage Digital, the first chartered crypto bank, rents a regulated balance sheet that understands Solidity. Franklin Templeton directly mints its Benji Treasury fund onto Anchorage custody, settling shares T+0 instead of T+2.

Coinbase Cloud offers wallet issuance, MPC custody, and sanctions-checked transfers as a single API.

These players possess elements missing from traditional vendors: understanding of on-chain assets, compliance and AML built into protocols, and event-driven APIs instead of batch files. Contrast this with a market expected to grow from ~$17 billion today to ~$65 billion by 2032, and the equation is simple: line items once owned by Fidelity and its peers are now up for grabs, and companies delivering products in Rust and Solidity—not Cobol—will capture them.

But before they’re truly retail-ready, they must battle the great demon all financial products face: compliance. In an increasingly on-chain world, what might compliance look like?

Code as Compliance

Banks run four types of compliance: know-your-customer (KYC and due diligence), counterparty screening (sanctions and PEP checks), transaction monitoring (with alerts and investigations), and reporting to regulators (SARs/CTRs, audits). This is massive, expensive, and ongoing. Global spending exceeded $274 billion in 2023, and the burden grows nearly every year.

The scale of paperwork reveals the risk model. FinCEN tallied about 4.7 million suspicious activity reports and 20.5 million currency transaction reports last year—forms submitted after the fact about risks. This work is batch-heavy: collecting PDFs and logs, compiling narratives, submitting reports, waiting.

For on-chain transactions, compliance no longer operates as a pile of manual artifacts but begins to function like a real-time system. FATF’s “Travel Rule” requires originator/beneficiary information to travel with transfers; crypto providers must collect, hold, and transmit this data (traditionally above $1,000 thresholds for “occasional transactions” in USD/EUR). The EU goes further, applying the rule to all crypto transactions. On-chain, this payload can be sent as encrypted data blocks with transfers—visible to regulators but not the public. Chainlink and TRM publish sanction lists and fraud oracles; transfers query these lists mid-process and revert if an address is flagged.

Once zero-knowledge wallets like Polygon ID or World ID can carry encrypted badges proving, say, “I am over 18 and not on any sanctions list,” privacy is preserved. Merchants see green lights, regulators get auditable trails, users never leak passport scans or street addresses.

If funds stall in back-office paperwork, fast, fluid markets are useless. Vanta exemplifies a reg-tech startup moving SOC2 compliance from consultants and screenshots to APIs. Startups selling software to Fortune 500 companies need SOC2 certification. This should prove adherence to sound security practices, avoiding storage of customer data in unprotected public links.

Startups hire auditors who deliver giant spreadsheets demanding screenshots—from AWS settings to Jira tickets—disappear for six months, then return with a signed PDF that’s already expired. Vanta turns this ordeal into an API. Instead of hiring consultants, plug Vanta into AWS, GitHub, and your HR tech stack; it monitors logs, automatically takes the same screenshots, and delivers them to auditors. This trick has propelled Vanta to $200 million in annual recurring revenue (ARR) and a $4 billion valuation.

Linear’s founders lament the state of compliance

Finance will follow the same path: less binder management, more policy engines assessing events in real time and leaving cryptographic receipts. Balances and flows are transparent, timestamped, and cryptographically signed—so auditing becomes observation.

Oracles like Chainlink act as truth carriers between off-chain rulebooks and on-chain execution. Its Proof-of-Reserve data feeds make reserve adequacy legible to contracts, so issuers and venues can connect automatic circuit breakers. No need to wait for annual audits—ledgers are monitored continuously.

Proof-of-Reserve gradually reaches liquid collateral levels; if a stablecoin’s backing ratio drops below 100%, minting locks automatically and regulators are notified.

Practical work remains. Identity verification, cross-jurisdictional rules, edge-case investigations, and machine-readable policies all need strengthening. The coming years won’t feel like paperwork drudgery but more like API version control: regulators publish machine-readable rules, oracle networks and compliance vendors provide reference adapters, auditors shift from sampling to oversight. As regulators grasp what real-time auditing enables, they’ll collaborate with vendors to implement a new class of tools.

A New Era of Trust

Everything gets bundled, then steadily unbundled. The human story is one of repeatedly trying to boost efficiency by integrating things, only to realize decades later they’re better kept apart. The nature of legislation (around stablecoins) and the state of underlying networks (Arbitrum, Solana, Optimism) mean we’ll see repeated attempts to rebuild banks. Yesterday, Stripe announced its own attempt to launch an L1.

Two forces are converging in modern society:

-

Rising costs due to inflation.

-

Rising meme-driven desires due to our highly interconnected world.

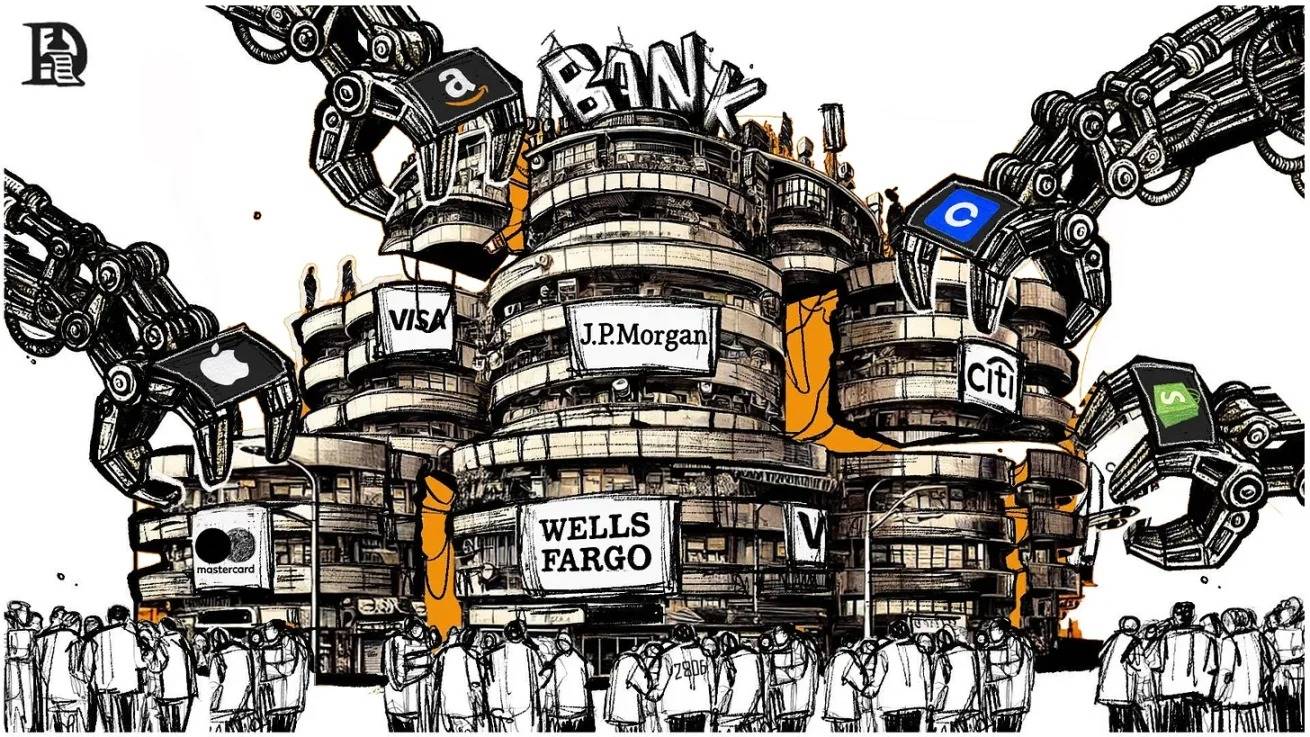

In an era where consumption desires rise but wages stagnate, more people will take control of their finances. The GameStop surge, the rise of meme coins, and even the frenzy around Labubu or Stanley cups are all effects of this shift. It means apps with sufficient distribution power and embedded trust will evolve into banks. We’ll see versions of Hyperliquid’s builder code system extend across the entire financial world. Whoever owns distribution will ultimately become the bank.

If your most trusted influencer recommends a portfolio on Instagram, why trust JPMorgan? If you can trade directly on Twitter, why bother with Robinhood? Me? Personally? My preferred way to lose money would be keeping funds on Goodreads to buy rare books. My point is, with the GENIUS Act, legislation allowing products to hold user deposits has changed. In a world where the moving parts of banking become API calls, more products will mimic banks.

Platforms with feeds will lead this shift—it’s not a new phenomenon. Early social networks heavily relied on e-commerce platform activity for monetization because that’s where money changed hands. Users seeing ads on Facebook might buy products on Amazon, generating referral revenue for Facebook. In 2008, Amazon launched Beacon, an app specifically viewing platform activity to create wishlists. Throughout web history, there’s been an elegant waltz between attention and commerce. Embedding banking infrastructure within platforms is just another mechanism to get closer to where the money is.

Won’t legacy players jump on the trend of providing digital asset access? Won’t existing fintech companies sit idle? FIS negotiates with nearly every bank and knows what’s happening. Ben Thompson’s point in his recent article is simple and brutal: when paradigms flip, yesterday’s winners are at a disadvantage because they want to keep doing what made them win. They optimize for the old game, defend old KPIs, and make correct decisions for the wrong world. That’s the winner’s curse—and it applies equally to capital going on-chain.

When everything is a bank, nothing is a bank. If users don’t trust a single platform to hold most of their wealth, fund storage will fragment. This is already happening for crypto-native users who keep most of their wealth on exchanges rather than banks. It means the unit economics behind banking revenue will change. Smaller apps may not need as much revenue as big banks to operate, since most of their operations could happen without human intervention. But this implies traditional banks as we know them will slowly fade away.

Perhaps, like life itself, technology is just a continuum of creation and destruction, bundling and unbundling.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News