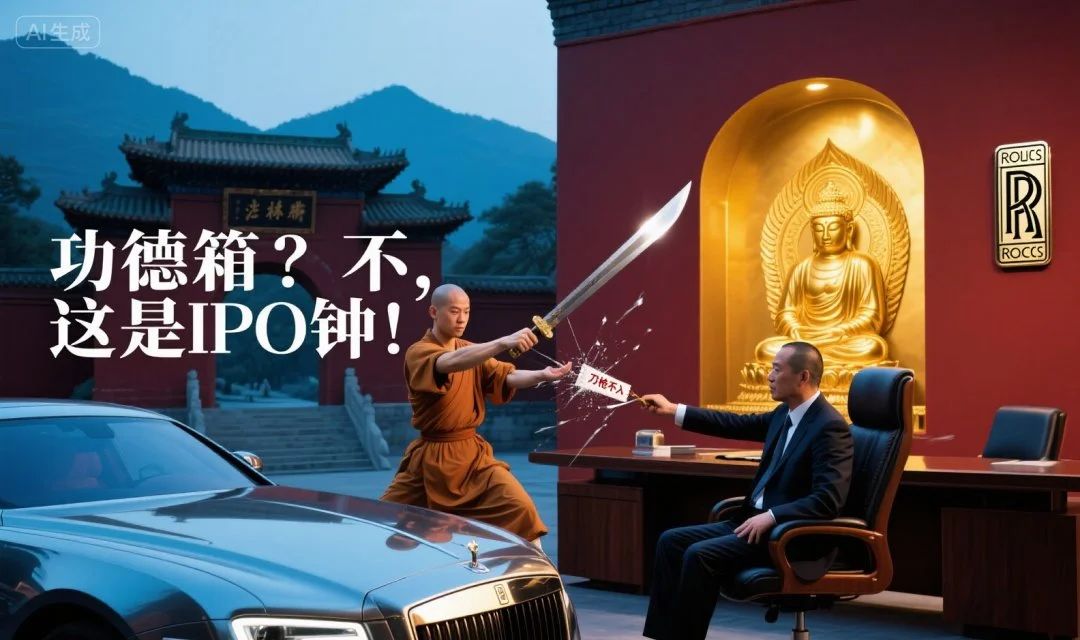

The Buddhist CEO's Capital Puzzle: The Fall from Ancient Temple to Business Empire

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Buddhist CEO's Capital Puzzle: The Fall from Ancient Temple to Business Empire

In the pure land of Buddhism, a storm not to be underestimated has arisen. At the heart of this storm is the "Buddhist business empire" built over 26 years by Abbot Shi Yongxin, a CEO in monk's robes.

PART .01 Case Overview: Unveiling the Collision of Capital and Monastic Discipline

On July 27, 2025, an announcement from the Shaolin Temple's official website sent shockwaves through public discourse: Abbot Shi Yongxin is under joint investigation by multiple agencies for allegedly misappropriating temple assets (amounting to possibly 800 million yuan) and maintaining improper relationships with multiple women, fathering illegitimate children.

The sacred Buddhist ground has become the center of a significant scandal. At its core lies the "Buddhist business empire" built over 26 years by Abbot Shi Yongxin—the CEO in robes. From launching China’s first temple website in 1996, to establishing Henan Shaolin Intangible Asset Management Co., Ltd. in 2008 focused on investment, which became a key platform for commercial operations—making 16 external investments totaling nearly 80 million yuan, with a single largest investment reaching 16 million yuan—to acquiring commercial land in Zhengzhou for 452 million yuan in 2022, his commercial reach spans culture, tourism, real estate, and finance, generating annual revenue exceeding 1.5 billion yuan.

However, under penetrating scrutiny by the investigation team, a layered “nested doll” financial black hole has emerged: 800 million yuan in ticket revenue was funneled through a dual-layer SPV structure into personally controlled companies, then transferred under the guise of “international Buddhist propagation” to the British Virgin Islands, amounting to 130 million yuan used to purchase apartments in London, with rental income laundered back into the temple donation box via Bitcoin, forming a perfect money-laundering loop.

PART .02 Key Facts: The Legal Boundary Between Fund Misappropriation and Embezzlement

The Battle Over Subjective Intent

Is International Buddhist Propagation Genuine Outreach or a False Cover?

Between 2016 and 2024, Shi Yongxin remitted 130 million yuan monthly to a British Virgin Islands company under the name of “international Buddhist propagation,” totaling over 1.5 billion yuan. These funds were ultimately used to purchase a 130 million yuan apartment in Kensington, London, registered under the name of his nephew Liu, with rental income flowing back to the temple donation box via Bitcoin wallets, creating a closed loop of “funds outbound - asset acquisition - profit repatriation.”

According to Articles 271 and 272 of the Criminal Law, the key distinction between embezzlement and fund misappropriation lies in whether the perpetrator had the intent to illegally possess the funds.

If Shi Yongxin used the funds for personal investments, such as purchasing property in London, and concealed the flow using Bitcoin laundering, this could be deemed permanent possession, fitting the characteristics of embezzlement.

But if he can prove intent to repay—for example, by fabricating the “international Buddhist propagation” project as a cover—then it may constitute fund misappropriation. However, investigators found that he transferred funds via USDT to overseas casino accounts without any trace of repayment, indicating stronger evidence of intentional embezzlement.

Building the Evidence Chain: Methods of Action

Funds Disguised as Legitimate Transactions?

In 2023, Henan Shaolin Martial Arts Equipment Factory (controlled by Shi Yongxin’s cousin Chen) sold “custom meditation garments” worth 30 million yuan to the Shaolin Temple. However, audits revealed that the actual production cost was only 8 million yuan, with the 22 million yuan difference funneled into Chen’s personal account through a “virtual inventory” accounting entry.

Meanwhile, the Shaolin Temple and Shaolin Intangible Asset Management Company shared the same financial system. A 2024 payment labeled “overseas Buddhist propagation expense” of 12 million yuan was actually used to cover property management fees, utilities, and electricity for the London apartment, yet was not separately listed in the temple’s books.

These actions clearly align with the behavioral traits of embezzlement, typically involving forged accounts and fictitious transactions. In contrast, fund misappropriation usually involves unauthorized use of funds without concealment—for instance, directly diverting funds for personal consumption.

The Special Nature of Religious Property

Legal Flaws and Commercial Abuse?

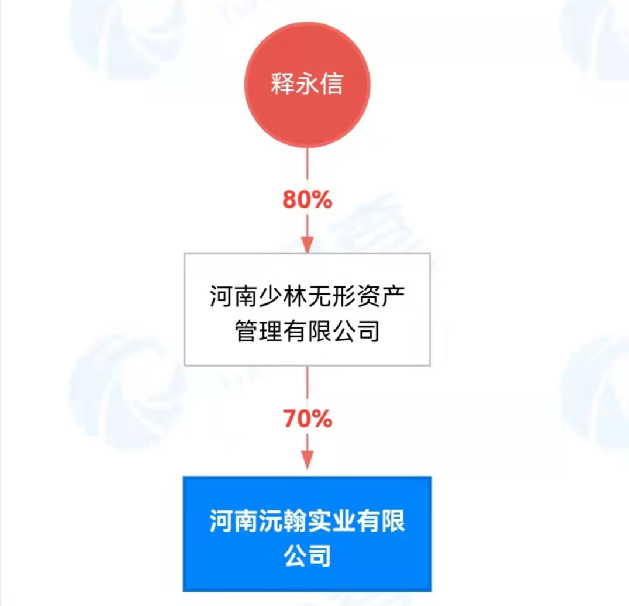

Shi Yongxin, the abbot who presents an image of monastic poverty, in reality holds the position of CEO with 80% ownership in Henan Shaolin Intangible Asset Management Co., Ltd. Though claiming to be a nominee shareholder, no agreement was filed with the Henan Provincial Religious Affairs Bureau. Moreover, the company charter states that shareholders must sign a commitment letter renouncing ownership, disposal rights, and profit rights—yet in practice, profits were funneled to his personal account through related-party transactions.

This clearly constitutes abuse of authority. Religious leaders are required to comply with the “Financial Management Measures for Religious Activity Sites,” mandating strict separation between personal and religious property.

Trademarks reflect the continuous expansion of Shaolin Temple’s commercial footprint. The temple has registered the trademark “Shaolin” across 706 product categories. However, without approval from the temple management committee, Shi Yongxin unauthorizedly licensed the trademark to “Shaolin International Holdings Limited,” controlled by his nephew Liu, charging an annual licensing fee of 50 million yuan that was never recorded in the temple’s financial statements.

This violates the “Regulations on Religious Affairs” and the “Management Measures for Religious Personnel,” which stipulate that religious leaders (such as abbots) are limited to managing religious affairs, while major asset decisions require collective resolution by a religious body or management committee.

PART .03 Valley Analysis: Legal Pathways from Financial Tracing to Cross-Border Asset Recovery

Constructing a Triple Evidence Chain for Embezzlement

First Layer of Evidence—Financial Penetration Audit

To prove that Shi Yongxin used “fictitious transactions” to transfer temple funds into personal accounts, investigators can trace how payments labeled “overseas Buddhist propagation expenses” were actually used to pay for the London apartment’s management fees. Combined with blockchain analysis tools tracking USDT flows to overseas casinos, a complete financial lineage map can be established.

Second Layer of Evidence—Proof of Financial Commingling

In this case, the Shaolin Temple and Henan Shaolin Intangible Asset Management Company maintained commingled accounts. Between 2016 and 2024, the “International Buddhist Propagation” sub-account remitted 130 million yuan monthly to a British Virgin Islands entity, without corresponding service contracts or records of fund repatriation, satisfying Article 271 of the Criminal Law regarding “illegally appropriating organizational property for personal gain.”

Third Layer of Evidence—Presumption of Subjective Intent

If Shi Yongxin cannot present a repayment plan or demonstrate actual repayment, and if the funds were used for high-risk investments (e.g., Bitcoin) or personal asset purchases (with the London apartment titled to his nephew), courts may infer intent to unlawfully possess the funds.

Defensive Grounds and Challenges for Fund Misappropriation

Based on current information, Shi Yongxin may find it strategically favorable to claim fund misappropriation rather than embezzlement, but he must provide the following evidence:

① Written documentation of a repayment plan, such as promissory notes or repayment agreements, demonstrating intent to return the funds.

② Proof of legitimate fund usage, including actual expenditure records for the “international Buddhist propagation” project.

③ Timely repayment within three months, showing the funds were not used for profit-making or illegal activities and were returned promptly.

However, investigators have already uncovered a Bitcoin-based money laundering loop concealing the fund trail, and the misuse spanned eight years—leaving extremely limited room for defense.

Challenges in Cross-Border Asset Recovery

The 130 million yuan London apartment purchased via a British Virgin Islands company raises a critical issue: cross-border asset recovery.

Under the “Law on International Judicial Assistance,” investigators must proceed as follows: First, obtain property title records and bank transaction logs from UK land registries, authenticated under the Hague Convention; Second, coordinate through Interpol to request cryptocurrency exchanges to disclose wallet address linkages for USDT transactions; Third, invoke the United Nations Convention against Corruption to petition UK courts to freeze the涉案 property; Finally, through judicial cooperation mechanisms, repatriate the recovered assets to the temple.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News