Bitcoin Security Vulnerability: Time Warp Attack

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Bitcoin Security Vulnerability: Time Warp Attack

In this article, we analyze a security vulnerability in Bitcoin known as the time warp attack.

Author: BitMEX Research

Overview

On March 26, 2025, Bitcoin developer Antoine Poinsot released a new Bitcoin Improvement Proposal (BIP). This is a soft fork proposal known as the "Great Consensus Cleanup." The upgrade fixes several long-standing bugs and weaknesses in the Bitcoin protocol. One of these vulnerabilities is the duplicate transaction issue we recently discussed. Another more serious vulnerability that this cleanup soft fork will fix is known as the "Time Warp Attack," which is the subject of this article.

Bitcoin Block Timestamp Protection Rules

Before discussing the time warp attack, let's review the current rules protecting against time manipulation:

Median Past Time (MPT) Rule — The timestamp must be later than the median of the timestamps of the last eleven blocks.

Future Block Time Rule — Based on the MAX_FUTURE_BLOCK_TIME constant, the timestamp cannot exceed the median network time by more than two hours. A maximum allowed deviation of 90 minutes between peer-provided time and the node’s local clock provides an additional safeguard.

The MPT rule ensures that blocks do not move too far into the past, while the future block rule prevents them from moving too far into the future. Note that a rule similar to the future block rule cannot be enforced to prevent past timestamps, as it could interfere with initial blockchain synchronization. The time warp attack involves forging timestamps to make them appear far in the past.

Satoshi's Off-by-One Error

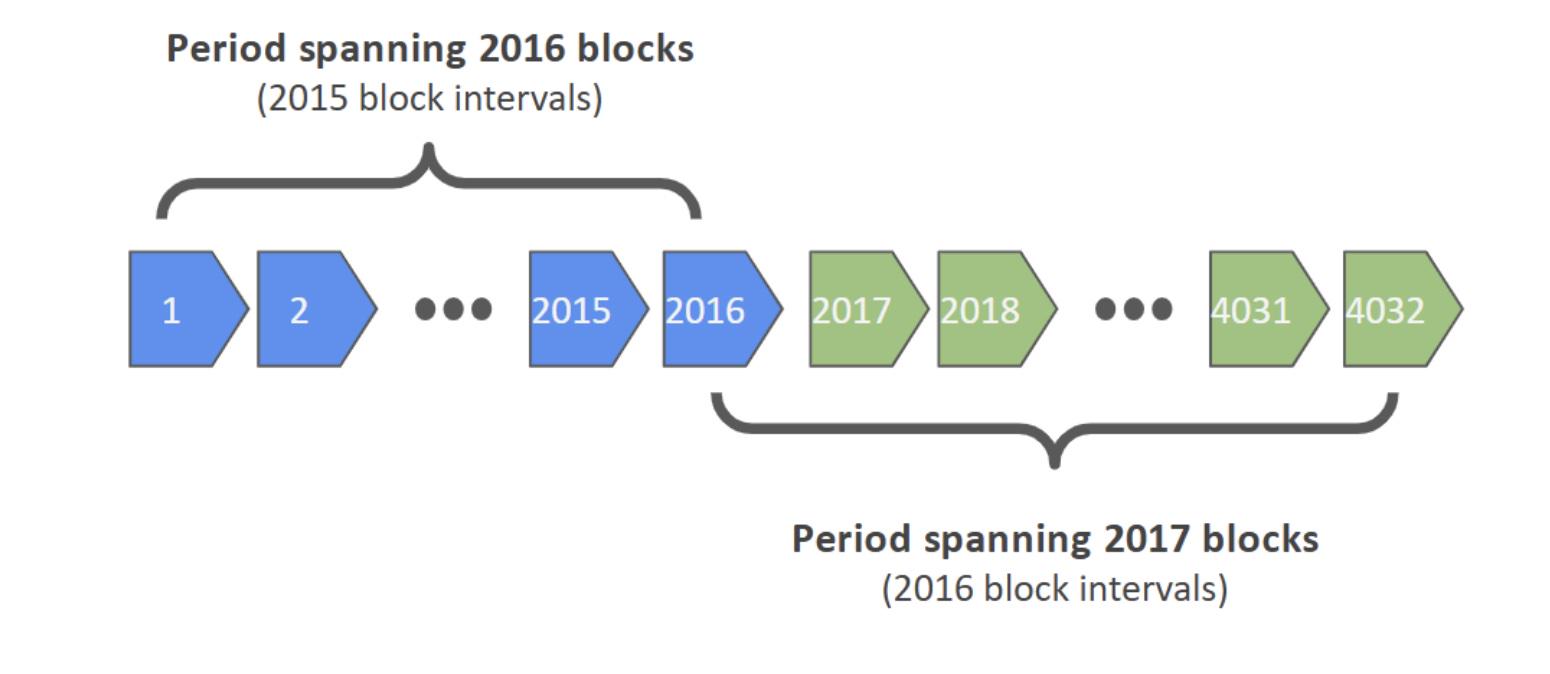

In Bitcoin, a difficulty adjustment period consists of 2016 blocks, which at a 10-minute block target equates to approximately two weeks. To calculate the mining difficulty adjustment, the protocol computes the difference between the timestamps of the first and last blocks within this 2016-block window. This window contains 2015 intervals between blocks (i.e., 2016 minus one). Therefore, the relevant target time should be 60 seconds × 10 minutes × 2015 intervals = 1,209,000 seconds. However, the Bitcoin protocol uses the number 2016 in its calculation: 60 seconds × 10 minutes × 2016 = 1,209,600 seconds. This is an off-by-one error—an easy mistake to make, and it appears Satoshi confused the count of blocks with the number of intervals between them.

Original Satoshi Code

Source: https://sourceforge.net/p/bitcoin/code/1/tree//trunk/main.cpp#l687

This error means the target time is 0.05% longer than it should be. As a result, Bitcoin's actual block interval is not exactly 10 minutes, but rather 10 minutes and 0.3 seconds. While this flaw is minor, in practice, the average block interval since Bitcoin’s launch has been 9 minutes and 36 seconds—clearly less than 10 minutes—due to consistently increasing hash power since 2009. This is why the most recent halving occurred in April 2024 instead of January 2025; we are ahead of schedule. Regardless, Satoshi’s 0.3-second error is largely negligible overall. Perhaps in the distant future, when price and hash power stop growing, this quirk might help bring us back in line with the intended timeline.

While the 0.3-second discrepancy itself is not significant, there is a related issue that constitutes a more serious vulnerability. The difficulty calculation relies solely on the first and last blocks within each 2016-block window. This approach is flawed. In our view, the correct reference period should be the time difference between the last block of the previous 2016-block window and the last block of the current window. This would seem to be the most logical way to measure the duration across adjustment periods, ensuring continuity between cycles. If implemented this way, using 2016 as the interval count would also be correct. Perhaps Satoshi made this error because he had to account for the very first difficulty adjustment period, for which no prior cycle’s final block was available.

Time Warp Attack

The Bitcoin time warp attack was first identified around 2011 and exploits the error in Satoshi’s difficulty calculation. To execute the attack, assume mining is 100% centralized and miners can set any timestamp permitted by the protocol. In the attack, for nearly all blocks, the miner sets the timestamp just one second ahead of the previous block, allowing the blockchain to progress forward in time while complying with the MTP rule. Alternatively, to minimize forward movement of time, the miner may keep the same timestamp for six consecutive blocks, then advance it by one second on the seventh, repeating this pattern. This results in the block timestamp advancing by only one second every six blocks.

This strategy causes the blockchain to increasingly lag behind real-world time, causing difficulty to rise and mining to become progressively harder. However, to amplify the attack, at the final block of each difficulty adjustment period, the miner sets the timestamp to match real-world time. Then, the next block—the first block of the new difficulty window—is timestamped slightly into the past, specifically one second earlier than the second-to-last block of the previous difficulty window. This still complies with the MPT rule, as such anomalies do not affect the median of the last eleven timestamps.

When executed, the first difficulty adjustment after initiating the attack remains unaffected. However, during the second adjustment cycle, the calculated elapsed time appears artificially long due to the manipulated timestamps, triggering a downward difficulty adjustment. Miners can then rapidly produce blocks, potentially creating a large number of bitcoins, which they may sell for profit.

Simplified Illustration

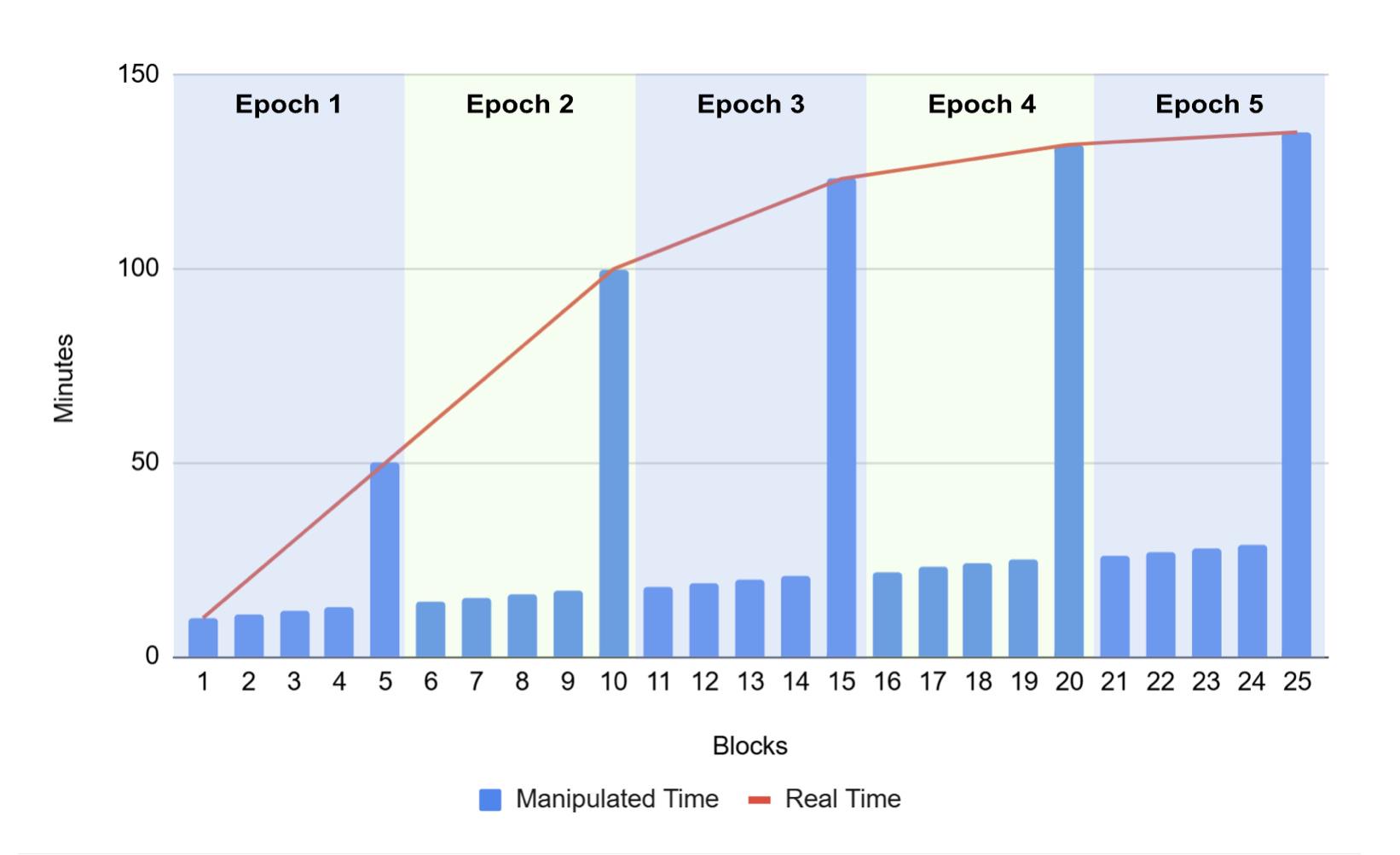

Because difficulty periods consist of 2016 blocks, illustrating this attack in a diagram can be challenging. Therefore, we present the following simplified scenario to explain the mechanism:

-

Each difficulty adjustment window consists of five blocks

-

Target block interval is 10 minutes

-

MTP rule is based on the last three blocks

-

Each block's timestamp increases by one minute, except for the last block in each cycle, which uses the real-world timestamp

Illustrative Time Warp Attack

As shown in the chart above, there are two curves:

-

A curve representing the real-world time of the last block in each difficulty adjustment window. As miners find blocks faster due to reduced difficulty, this curve becomes less steep over time

-

A straight line representing the manipulated timestamps of other blocks

Bitcoin Time Warp Attack Calculation

The table below shows how miners could exploit this attack to maximally manipulate difficulty downward.

Note: The maximum allowed difficulty adjustment per cycle is a factor of four, though this limit is not reached in the table.

The downward difficulty adjustment asymptotically approaches a value slightly above 2.8x. This occurs because as each cycle shortens in real time, the rate at which difficulty decreases slows down.

By the 11th cycle—on day 39 of the attack—more than six blocks are generated per second (specifically, 10.9 blocks per second). At this point, the constraints on timestamp allocation begin to behave differently. According to the MPT rule, time must advance by at least one second every six blocks. From this stage onward, under our understanding, timestamps start advancing faster relative to real time, causing the blockchain clock to begin catching up—approaching, though still significantly lagging behind, real-world time. Nevertheless, the attack can continue, with difficulty decreasing until it reaches the minimum allowable level.

Attack Feasibility

While theoretically devastating, implementing this attack presents several challenges. It likely requires control of the majority of hash power. If honest miners include accurate timestamps, the attack becomes significantly harder. The MTP rule combined with honest timestamps may limit how far back malicious miners can set their timestamps. Moreover, if an honest miner produces the first block of any difficulty adjustment window, the attack for that cycle fails. Another mitigating factor is visibility: the manipulation would be evident to anyone monitoring timestamps. The need to manipulate timestamps over several weeks before a downward difficulty adjustment provides a potential window to deploy an emergency soft fork fix.

Solution

Fixing this vulnerability is relatively straightforward, though it may require a protocol soft fork. Directly fixing the root cause—by modifying the difficulty adjustment algorithm to measure time spans between corresponding blocks in consecutive 2016-block windows and fully correcting the off-by-one error—would be complex and might necessitate a hard fork. An alternative approach would be to eliminate the MTP rule entirely and require timestamps to always increase with each block. However, this could cause issues—for example, time might get stuck too far ahead, or miners using accurate system clocks could face invalid timestamps if another miner’s clock is slightly ahead.

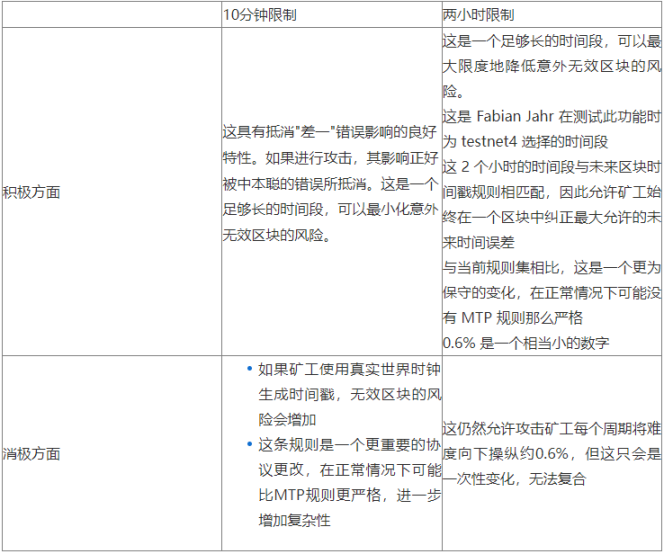

Luckily, there is a simpler solution. To prevent the time warp attack, we only need to require that the first block of a new difficulty period cannot have a timestamp earlier than a certain number of minutes before the last block of the previous period. The exact number of minutes for this grace period has been debated, with proposals ranging from 10 minutes to 2 hours. For mitigating the time warp attack, either value would likely suffice.

In Poinsot’s Great Consensus Cleanup proposal, the chosen value is now set at 2 hours. Since 2 hours is only about 0.6% of the target duration of a difficulty adjustment cycle, the ability to manipulate difficulty downward is strictly limited. We summarize the discussion on the appropriate grace period in the table below:

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News