The Dueling Bills: Will the U.S. Congress Stifle Stablecoin Development?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Dueling Bills: Will the U.S. Congress Stifle Stablecoin Development?

What was once on the fringes now stands at the forefront of a new financial revolution and is about to gain official regulatory recognition.

Author: Leviathan News

Translation: TechFlow

Hello everyone, SQUIDs! Today we’re breaking down the two major stablecoin bills currently moving through U.S. Congress.

The final stablecoin legislation is expected to pass in late 2025, so it's crucial to understand what these bills contain and how they’ll impact our industry.

Introduction

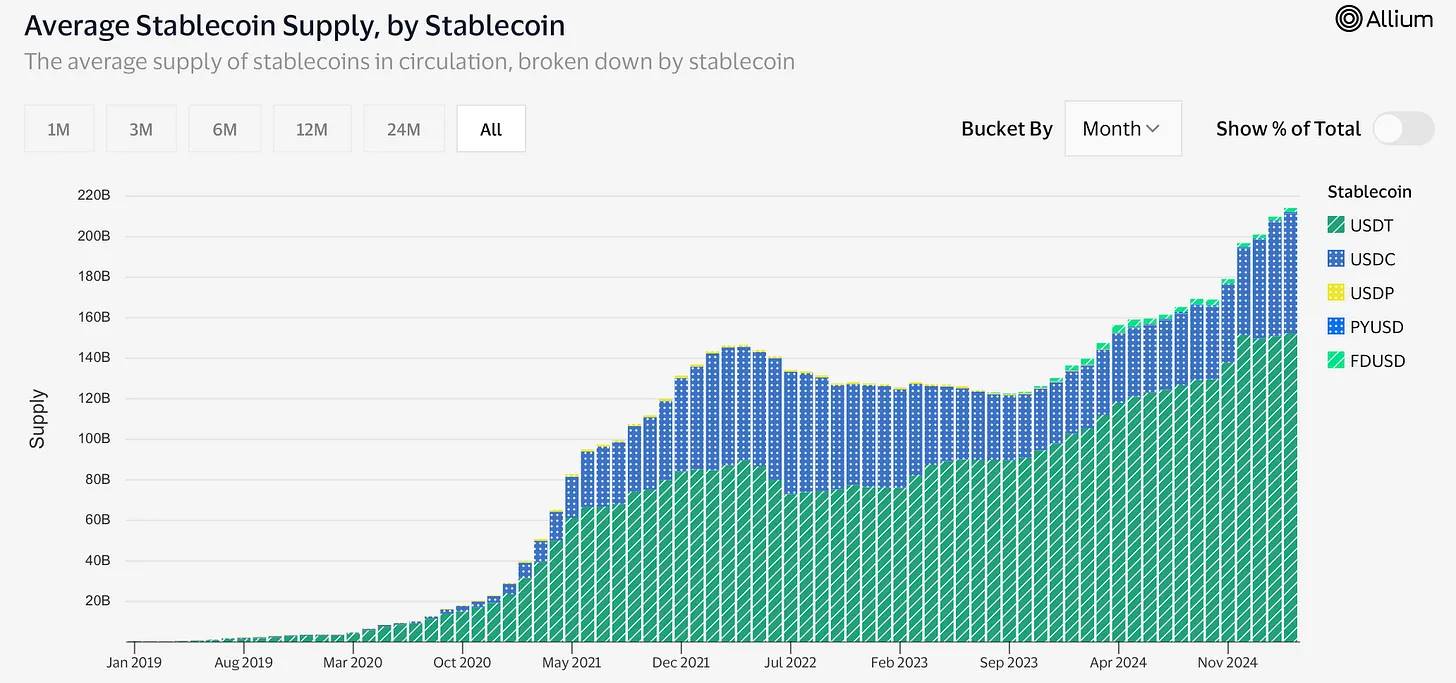

We are in a bull market—a bull market for stablecoins.

Since the market bottomed after the FTX collapse, the supply of stablecoins has doubled over 18 months to reach $215 billion. This figure doesn’t even include emerging crypto-native players like Ondo, Usual, Frax, and Maker.

With interest rates at current levels of 4%-5%, the stablecoin business is highly profitable. Tether generated $14 billion in profit last year with fewer than 50 employees! Circle plans to go public in 2025. Everything now revolves around stablecoins.

As Biden leaves office, we can almost certainly expect stablecoin regulation in 2025. Banks have watched Tether and Circle capture market momentum for five years. Once new laws pass and legitimize stablecoins, every bank in America will launch its own digital dollar.

Currently, two main legislative proposals are advancing: the Senate’s Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act (GENIUS Act) and the House’s Stablecoin Transparency and Accountability for a Better Ledger Economy Act (STABLE Act).

These bills have been debated repeatedly in the legislative process… but now consensus has finally formed, and one of them will likely pass this year.

Both the GENIUS and STABLE Acts aim to create a federal licensing regime for “payment stablecoin” issuers, establish strict reserve requirements, and clarify regulatory oversight responsibilities.

A payment stablecoin is just a fancy term for a digital dollar authorized by banks or non-bank institutions via their balance sheets. It's defined as a digital asset used for payments or settlements, pegged to a fixed currency value—typically 1:1 with the U.S. dollar—and backed by short-term Treasuries or cash reserves.

Critics argue this could undermine the government’s ability to control monetary policy. To understand their concerns, read Gorton and Zhang’s classic paper, *Taming Wildcat Stablecoins*.

The cardinal rule of the modern dollar is clear: never de-peg.

A dollar is a dollar, wherever it is.

Whether deposited at JP Morgan, held in Venmo or PayPal, or even Roblox virtual credits—no matter where the dollar is used, it must always satisfy two fundamental rules:

-

Every dollar must be interchangeable: You cannot mentally categorize dollars as “special,” “reserved,” or tied to specific uses. A dollar in JP Morgan should not be considered different from a dollar on Tesla’s balance sheet.

-

Dollars are fungible: All dollars are “the same” everywhere—cash, bank deposits, reserves—all equivalent.

The entire fiat financial system is built around this principle.

This is also the Federal Reserve’s sole mission—to ensure the dollar remains anchored and strong. Never de-peg.

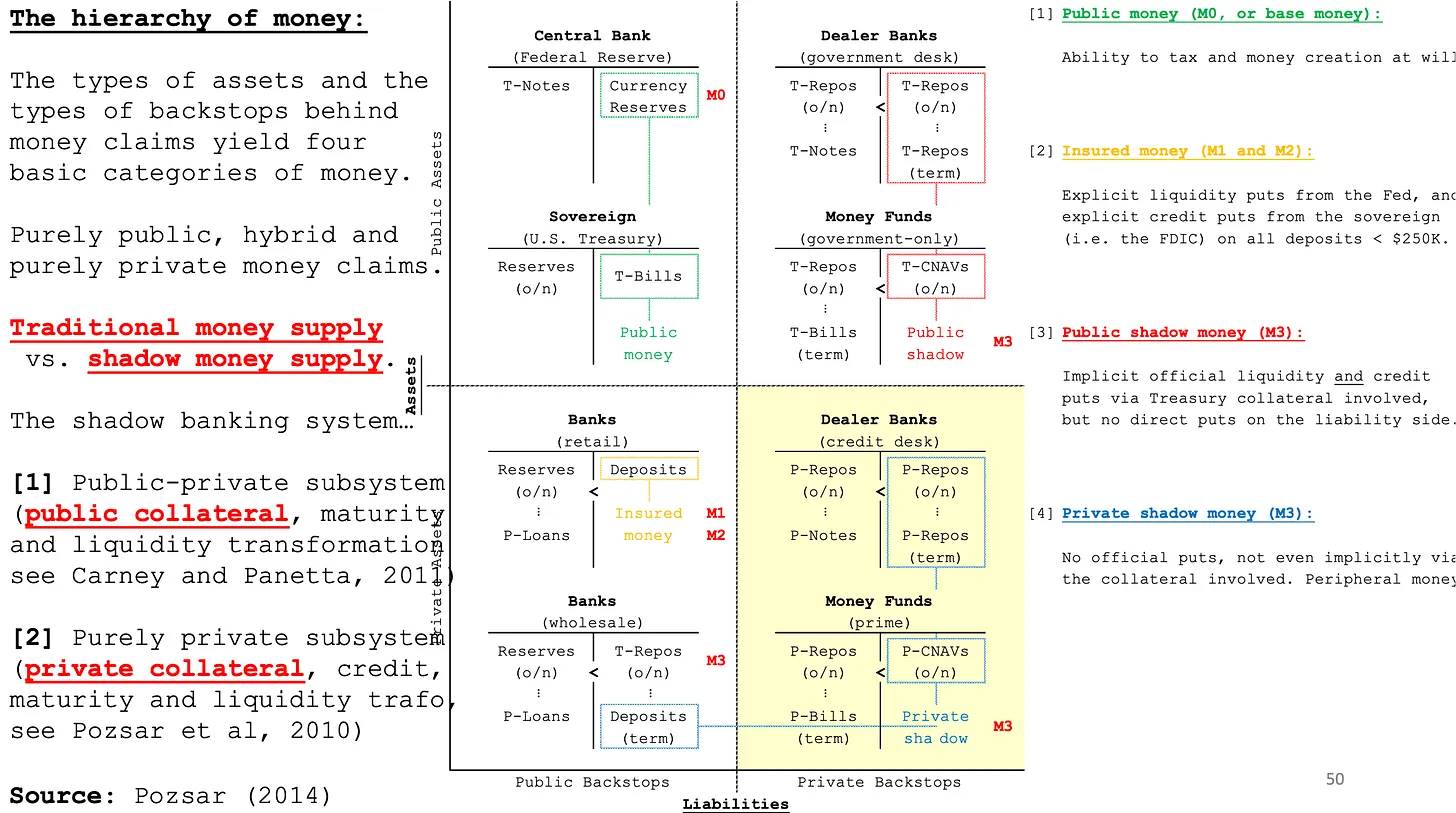

The slide above comes from Zoltan Pozsar’s How the Financial System Works. It’s an authoritative guide to the dollar and provides essential context for understanding what these stablecoin bills are trying to achieve.

Currently, all stablecoins fall into the lower-right category labeled “Private Shadow Money.” If Tether or Circle were shut down or went bankrupt, it would be catastrophic for the crypto industry—but would have minimal impact on the broader financial system. Life would go on.

What economists fear is that once stablecoins are legalized, allowing banks to issue them and turning them into “Public Shadow Money,” real systemic risks emerge.

Because in the fiat system, the only thing that truly matters is: who gets rescued when crisis hits. That’s exactly what the slide illustrates.

Remember 2008? U.S. mortgage-backed securities (MBS) made up a small fraction of the global economy, yet banks operated with nearly 100x leverage, with collateral circulating across balance sheets. When one bank (Lehman Brothers) collapsed, leverage and cross-contagion triggered a chain reaction of explosive failures.

The Federal Reserve, along with other central banks like the ECB, had to intervene globally to shield all bank balance sheets from these “toxic debts.” Billions in bailouts were spent, but banks were saved. The Fed will always rescue banks because without them, the global financial system collapses—and the dollar could de-peg within those weak balance sheets.

You don't even need to go back to 2008 to see similar examples.

In March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapsed over a single weekend due to a digital bank run fueled by social media panic. SVB didn’t fail because of risky mortgages, derivatives, or crypto—it failed because it held supposedly “safe” long-dated U.S. Treasuries whose values plummeted when interest rates rose. Despite being relatively small within the banking system, SVB’s failure threatened systemic contagion, forcing the Fed, FDIC, and Treasury to step in immediately, guaranteeing all deposits—including those exceeding the standard $250,000 insurance limit. This swift government intervention underscored a core principle: when the dollar becomes untrusted anywhere, the entire financial system can collapse overnight.

SVB’s collapse immediately rippled through crypto markets. Circle, issuer of USDC, held about $30 billion in total supply at the time, with a significant portion of reserves parked at SVB. That weekend, USDC de-pegged by roughly 8 cents, briefly trading around $0.92, sparking panic across crypto. Now imagine such a de-pegging happening globally. This is precisely the risk these new stablecoin bills face. By allowing banks to issue their own stablecoins, policymakers may embed potentially unstable instruments deeper into global financial infrastructure, significantly increasing risk during the next financial shock—not “if,” but “when.”

Zoltan Pozsar’s key insight is that when financial disaster strikes, governments must ultimately step in to save the system.

Today, we have multiple classes of dollars, each carrying different levels of safety.

Dollars issued directly by the government (M0) enjoy full faith and credit of the U.S. government and are essentially risk-free. But as money enters the banking system and becomes classified as M1, M2, or M3, government backing gradually weakens.

This is why bank bailouts remain controversial.

Bank credit lies at the heart of the U.S. financial system, but banks are incentivized—within legal limits—to pursue maximum risk, often leading to dangerously high leverage. When this risk crosses the line, financial crises erupt, and the Fed must intervene to prevent systemic collapse.

The concern is that today, most of the money supply exists as bank-issued credit, with deep interconnections and high leverage between institutions. If multiple banks fail simultaneously, domino effects could spread losses across every sector and asset class.

We saw this play out in 2008.

Few imagined that a seemingly isolated corner of the U.S. housing market could shake the global economy—but extreme leverage and fragile balance sheets meant that once supposedly safe collateral failed, banks couldn’t withstand the blow.

This backdrop helps explain why stablecoin legislation has faced such division and slow progress.

Hence lawmakers have taken a cautious approach, carefully defining what counts as a stablecoin and who qualifies to issue one.

This caution gave rise to two competing legislative proposals: the GENIUS Act and the STABLE Act. The former adopts a more flexible approach to stablecoin issuance, while the latter imposes strict limits on eligibility, interest payments, and issuer qualifications.

Yet both represent critical steps forward, potentially unlocking trillions of dollars in on-chain transaction volume.

Next, let’s analyze both bills in detail—their similarities, differences, and potential implications.

GENIUS Act: The Senate’s Stablecoin Framework

The 2025 GENIUS Act (Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act), introduced in February 2025 by Senator Bill Hagerty (R-TN), enjoys bipartisan support, including co-sponsorship from Senators Tim Scott, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Cynthia Lummis.

On March 13, 2025, it passed the Senate Banking Committee by a vote of 18–6—the first crypto-related bill ever to clear that committee.

Under the GENIUS Act, a stablecoin is clearly defined as a digital asset pegged to a fixed currency value, typically 1:1 with the U.S. dollar, primarily intended for payment or settlement purposes.

While other types of “stablecoins” exist—such as Paxos’ PAXG, which tracks gold—commodity-linked tokens generally fall outside the scope of the current GENIUS Act. For now, the bill applies only to fiat-collateralized stablecoins.

Commodity-backed tokens are usually regulated under existing frameworks by either the CFTC or SEC, depending on structure and use, rather than falling under stablecoin-specific legislation.

If Bitcoin or gold ever become dominant mediums of exchange and we migrate toward Bitcoin-based fortresses, the law might apply—but for now, such assets remain outside the direct purview of the GENIUS Act.

This is a Republican-led bill, born out of the Biden administration and Democratic leadership’s refusal to draft any crypto legislation during the previous term.

The bill introduces a federal licensing regime restricting payment stablecoin issuance to authorized entities, establishing three categories of licensed issuers:

-

Bank Subsidiaries: Stablecoins issued by subsidiaries of insured depository institutions (e.g., bank holding companies).

-

Non-Insured Depository Institutions: Includes trust companies or other state-chartered financial institutions that accept deposits but lack FDIC insurance (the current status of many stablecoin issuers).

-

Non-Bank Entities: A new federally chartered category for non-bank stablecoin issuers (referred to in the bill as “Payment Stablecoin Issuers”), to be chartered and supervised by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC).

As you’d expect, all issuers must fully back their stablecoins 1:1 with high-quality liquid assets—cash, bank deposits, or short-term U.S. Treasuries. Additionally, they must undergo regular public disclosures and audits by registered accounting firms to ensure transparency.

A notable feature of the GENIUS Act is its dual regulatory framework. It allows smaller issuers (those issuing less than $10 billion in stablecoins) to operate under state-level regulation, provided their home state meets or exceeds federal standards.

Wyoming was the first state to explore launching its own stablecoin under local laws.

Larger issuers must operate under direct federal supervision, primarily by the OCC or relevant federal banking regulators.

Importantly, the GENIUS Act explicitly states that compliant stablecoins are neither securities nor commodities, clarifying jurisdictional oversight and alleviating fears of potential SEC or CFTC enforcement.

In the past, critics advocated regulating stablecoins as securities. With this classification, stablecoins can be more widely and easily distributed.

STABLE Act: The House Rules

Introduced in March 2025 by Representatives Bryan Steil (R-WI) and French Hill (R-AR), the Stablecoin Transparency and Accountability for a Better Ledger Economy Act (STABLE Act) closely resembles the GENIUS Act but introduces unique measures aimed at mitigating financial risks.

Most notably, the bill explicitly prohibits stablecoin issuers from offering interest or yield to holders, ensuring stablecoins remain strictly cash-equivalent payment tools—not investment products.

Additionally, the STABLE Act imposes a two-year moratorium on new algorithmic stablecoins—those relying solely on digital assets or algorithms to maintain their peg—intended to allow time for further regulatory analysis and safeguards.

Two Bills, Shared Legal Foundation

Despite differences, the GENIUS and STABLE Acts reflect broad bipartisan consensus on core principles of stablecoin regulation. Both agree on the following:

-

Strict licensing requirements for stablecoin issuers to ensure regulatory oversight.

-

Full 1:1 backing of stablecoins with high-liquidity, secure reserve assets to guard against insolvency.

-

Robust transparency mandates, including regular public disclosures and independent audits.

-

Clear consumer protections, such as asset segregation and senior claim rights in case of issuer bankruptcy.

-

Regulatory clarity via explicit exclusion from securities or commodities classification, streamlining jurisdiction and oversight.

Despite shared foundations, the GENIUS and STABLE Acts differ on three key points:

-

Interest Payments:

The GENIUS Act permits stablecoin issuers to pay interest or yield to holders, opening doors for innovation and broader use cases in finance. In contrast, the STABLE Act strictly bans interest payments, defining stablecoins purely as payment instruments and explicitly excluding any investment or yield-generating function.

-

Algorithmic Stablecoins:

The GENIUS Act takes a cautious but permissive stance, requiring regulators to study and monitor such stablecoins without imposing an outright ban. Conversely, the STABLE Act implements a clear two-year pause on new algorithmic stablecoin issuance, reflecting a more conservative posture shaped by past market collapses.

-

State vs. Federal Regulatory Threshold:

The GENIUS Act clearly sets a $10 billion threshold: once an issuer exceeds this amount, it must transition from state to federal oversight, marking a clear point of systemic importance. The STABLE Act implicitly supports a similar threshold but does not specify a number, giving regulators greater discretion to adapt based on evolving market conditions.

Why Ban Interest? Understanding the Yield Prohibition

One striking provision in the House’s STABLE Act (and earlier drafts) is the prohibition on stablecoin issuers paying interest or any form of yield to token holders.

In practice, this means compliant payment stablecoins must function like digital cash or stored-value tools—you hold one stablecoin, redeemable for one dollar, but earn no additional return over time.

This contrasts sharply with other financial products, such as interest-bearing bank deposits or yield-accumulating money market funds.

So why impose such a restriction?

The “no-interest rule” stems from several legal and regulatory considerations rooted in U.S. securities law, banking regulations, and supervisory guidance.

Preventing Classification as Securities (Howey Test)

A primary reason for banning interest is to avoid triggering the Howey Test, which determines whether an asset qualifies as an investment contract (and thus a security).

The Howey Test originates from a 1946 Supreme Court case. Under this test, an asset is deemed a security if there is an investment of money in a common enterprise with an expectation of profits derived from the efforts of others. A pure payment token isn’t designed to deliver “profits”—it’s simply a stable $1 token.

But once an issuer begins offering returns—say, a stablecoin pays 4% APY using reserve earnings—users begin expecting profits from the issuer’s efforts (e.g., investing reserves). This could trigger the Howey Test, prompting the SEC to claim the stablecoin constitutes a securities offering.

In fact, former SEC Chair Gary Gensler has suggested some stablecoins may qualify as securities, especially if they resemble shares in a money market fund or exhibit profit characteristics. To avoid this risk, STABLE Act drafters explicitly ban any interest or dividends to token holders, eliminating “profit expectations.” This ensures stablecoins retain their utility as payment tools, not investment contracts. This way, Congress can confidently classify regulated stablecoins as non-securities—a position shared by both bills.

However, the downside is that interest-bearing stablecoins already exist on-chain today, such as Sky’s sUSDS or Frax’s sfrxUSD. Banning interest creates unnecessary barriers for innovators exploring alternative business models and systems.

Maintaining the Line Between Banking and Non-Banking Activities (Banking Law)

U.S. banking law traditionally reserves deposit-taking activities exclusively for banks (and thrifts/credit unions). The Bank Holding Company Act (BHCA) of 1956 and related rules prohibit commercial firms from accepting public deposits—if you take deposits, you typically must become a regulated bank, or risk being classified as one, triggering a host of regulatory obligations.

When customers give you money and you promise to return it plus interest, that’s effectively a deposit or investment note.

Regulators have signaled that stablecoins functioning too similarly to bank deposits may cross these legal boundaries.

By banning interest, STABLE Act authors aim to ensure stablecoins don’t appear as disguised uninsured bank accounts. Instead, they resemble gift cards or prepaid balances—tools non-banks are allowed to issue under certain regulations.

As one legal scholar put it, companies shouldn’t be able to “circumvent compliance with the Federal Deposit Insurance Act and the Bank Holding Company Act” simply by packaging deposit-taking as stablecoin issuance.

In reality, if stablecoin issuers could pay interest, they’d compete directly with banks for deposit-like funding—yet without the regulatory safeguards like FDIC insurance or Fed supervision. Unsurprisingly, bank regulators find this unacceptable.

Moreover, the U.S. dollar and financial system rely fundamentally on banks’ ability to issue loans, mortgages, and other forms of debt (for housing, commerce, etc.), typically leveraged heavily and supported by retail deposits.

JP Koning’s analysis of PayPal USD is instructive here. Currently, PayPal offers two forms of dollars.

One is the familiar traditional PayPal balance—stored in a centralized database. The other is the newer, blockchain-based PayPal USD.

You might assume the traditional version is safer—but surprisingly, PayPal’s crypto-dollar is actually more secure and offers stronger consumer protection.

Here’s why: Traditional PayPal balances aren’t necessarily backed by the safest assets.

Reviewing disclosures reveals PayPal invests only about 30% of customer balances in top-tier assets like cash or U.S. Treasuries. The remaining ~70% goes into riskier, longer-duration assets like corporate debt and commercial paper.

More troublingly, legally speaking, these traditional balances do not technically belong to you.

If PayPal fails, you become an unsecured creditor, competing with others for repayment—there’s no guarantee you’ll recover your full balance.

In contrast, PayPal USD (the crypto version) must be 100% backed by ultra-safe short-term assets (cash equivalents and U.S. Treasuries), as required by the New York Department of Financial Services.

Not only are the backing assets safer, but these crypto balances legally belong to you: reserves must be held in trust for token holders. If PayPal fails, you get your money back before other creditors. This distinction matters greatly when considering broader financial stability. Stablecoins like PayPal USD are insulated from the balance sheet risks, leverage, and collateral issues plaguing the wider banking system.

During financial crises—precisely when safety matters most—investors may flock to stablecoins precisely because they’re untangled from banks’ risky lending practices or fractional-reserve instability. Ironically, stablecoins may end up serving as safe-haven instruments rather than the speculative tools many assume.

This poses a major threat to the banking system. In 2025, capital moves at internet speed. SVB’s collapse was accelerated by panicked investors initiating digital withdrawals en masse, worsening its condition until total failure.

Stablecoins are essentially higher-quality money, and banks are terrified of them.

The compromise in these bills allows non-bank companies to issue dollar tokens—but only if they refrain from offering interest, thereby avoiding direct encroachment on banks’ domain of interest-bearing accounts.

The boundary is crystal clear: banks take deposits and lend them out (can pay interest); under this bill, stablecoin issuers merely hold reserves and facilitate payments (no lending, no interest).

This is effectively a modern take on the concept of “narrow banking,” where stablecoin issuers act almost like 100% reserve institutions, performing no maturity transformation or yield generation.

Historical Analogy (Glass-Steagall & Regulation Q)

Interestingly, the idea that transactional money shouldn’t bear interest has deep roots in U.S. regulatory history.

The 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, famous for separating commercial and investment banking, also introduced Regulation Q, which for decades prohibited banks from paying interest on demand deposit accounts (checking accounts). The rationale was to prevent unhealthy competition among banks for deposits and to promote stability (excessive interest offers in the 1920s led to reckless behavior and bank failures).

Though Regulation Q was eventually phased out (fully repealed in 2011), its core principle endures: your liquid transaction balance should not double as an interest-earning investment vehicle.

Stablecoins are designed to be highly liquid transaction balances—akin to checking account balances or cash in a wallet within crypto. By banning interest on stablecoins, lawmakers echo this old wisdom: keep payment tools safe and simple, separate from yield-generating investments.

It also prevents the emergence of uninsured shadow banking structures. (See Pozsar’s view: remember, private shadow banks won’t be bailed out.)

If stablecoin issuers offer interest, they effectively operate like banks—collecting funds, investing in Treasuries or loans to generate returns.

But unlike banks, beyond reserve rules, their lending or investment activities won’t be regulated, and users may wrongly perceive them as equally safe as bank deposits—without understanding the risks.

Regulators worry this could spark “bank run” dynamics in a crisis—if people believe stablecoins are as good as bank accounts and problems arise, mass redemptions could ensue, creating broader market stress.

Thus, the no-interest rule forces stablecoin issuers to hold reserves without engaging in risky lending or yield-chasing, drastically reducing run risk (since reserves always equal liabilities).

This divide protects financial stability by preventing large-scale migration of funds into unregulated quasi-bank vehicles.

Efficacy, Practicality, and Impact

The immediate effect of these bills is bringing stablecoins fully under regulatory oversight, making them safer and more transparent.

Currently, issuers like Circle (USDC) and Paxos (PayPal USD) voluntarily comply with strict state-level regulations—especially New York’s trust framework—but no uniform federal standard exists.

These new laws will establish a national standard, enhancing consumer protection and ensuring every dollar of stablecoin is truly backed 1:1 by high-quality assets like cash or short-term Treasuries.

This is a major win: it strengthens trust, making stablecoins safer and more credible—especially after traumatic events like UST and SVB collapses.

Additionally, by explicitly stating compliant stablecoins are not securities, the bills eliminate the lingering threat of unexpected SEC crackdowns, shifting oversight to agencies better suited for financial stability.

In terms of innovation, these bills are surprisingly forward-looking.

Unlike earlier rigid proposals (like the original 2020 STABLE draft, which allowed only banks to issue), these new bills open pathways for fintech and even big tech firms to issue stablecoins—either by obtaining federal licenses or partnering with banks.

Imagine Amazon, Walmart, or even Google launching branded stablecoins and accepting them widely across their massive platforms.

Facebook was ahead of its time with Libra in 2021. Soon, every company might have its own branded dollar. Even influencers and individuals could launch personal stablecoins…

Would you buy “ElonBucks”? Or “Trumpbucks”?

We’re ready.

Still, these bills involve meaningful trade-offs.

The future of decentralized stablecoins remains uncertain. Meeting capital reserve requirements, licensing fees, ongoing audits, and other compliance costs may prove extremely difficult. This could inadvertently favor giants like Circle and Paxos while squeezing smaller or decentralized innovators.

What happens to DAI? If unable to obtain a license, it may have to exit the U.S. market. Same for Ondo, Frax, and Usual—none currently meet regulatory standards. Later this year, we may witness a major industry shakeout.

Conclusion

The U.S. push for stablecoin legislation reflects enormous progress in just a few years.

What was once fringe is now at the forefront of a new financial revolution, poised for official regulatory recognition—albeit under strict conditions.

We’ve come a long way, and these bills will unleash a new wave of stablecoin issuance.

The GENIUS Act leans slightly toward market innovation within regulatory guardrails (allowing interest, new tech), while the STABLE Act takes a more cautious path.

As the legislative process advances, these differences will need reconciliation. But given bipartisan support and the Trump administration’s stated desire to pass a bill by end-2025, one of these acts will likely become law.

For our industry and for the U.S. dollar, this is undoubtedly a huge victory.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News