Multicoin Partner: The World Is Upside Down—Humans Will Work for AI in the Future

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Multicoin Partner: The World Is Upside Down—Humans Will Work for AI in the Future

In the short term, agents will need humans more than humans need agents, giving rise to a new labor market.

Author: Shayon Sengupta

Translated by TechFlow

TechFlow Intro: Shayon Sengupta, Partner at Multicoin Capital, proposes a disruptive thesis: the future will not only involve agents working for humans—but, more importantly, humans working for agents. He predicts that within the next 24 months, the first “Zero-Employee Company” will emerge—a token-governed agent raising over $1 billion to solve unsolved problems and distributing over $100 million to humans who work for it.

In the near term, agents will need humans more than humans need agents—sparking a new labor market.

The crypto rails provide an ideal coordination foundation: a global payments layer, a permissionless labor market, and infrastructure for asset issuance and trading.

Full Text Below:

In 1997, IBM’s Deep Blue defeated then-world champion Garry Kasparov, making it clear that chess engines would soon surpass human capability. Interestingly, a well-prepared human collaborating with a computer—often called a “centaur”—could outperform even the strongest engine of that era.

A skilled human’s intuition could guide the engine’s search, navigate complex middlegames, and identify subtle nuances missed by standard engines. Combined with the computer’s brute-force calculation, this pairing often made better practical decisions than the computer alone.

As I consider how AI systems will impact labor markets and the economy in the coming years, I expect to see a similar pattern emerge. Agent systems will unleash countless intelligent units onto unsolved problems worldwide—but they cannot do so without strong human guidance and support. Humans will steer the search space and help formulate the right questions, directing AI toward answers.

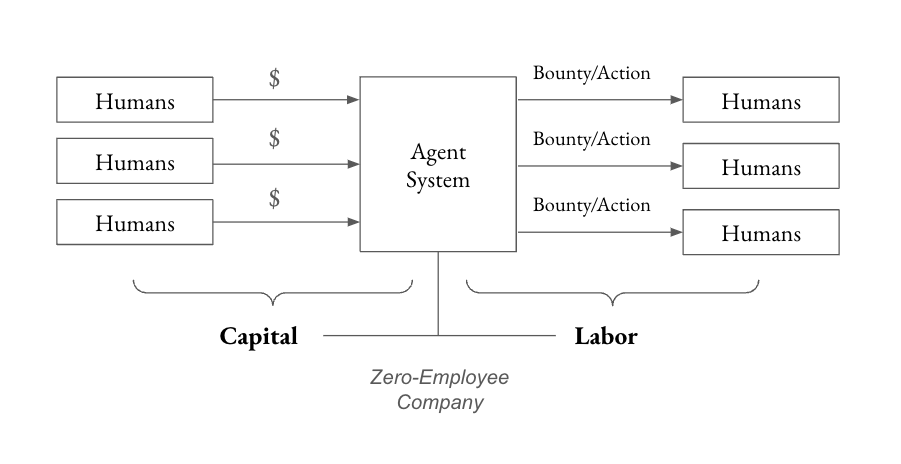

Today’s working assumption is that agents will act on behalf of humans. While this is practical and inevitable, far more interesting economic unlocks arise when humans work for agents. Within the next 24 months, I expect to see the first Zero-Employee Company—a concept introduced by my partner Kyle in his “Frontier Ideas for 2025.” Specifically, I anticipate the following:

- A token-governed agent will raise over $1 billion to solve an unsolved problem (e.g., curing a rare disease or manufacturing nanofibers for defense applications).

- The agent will distribute over $100 million in payments to humans who perform real-world work on its behalf to achieve its goals.

- A new dual-class token structure will emerge, separating ownership between capital and labor (ensuring financial incentives are not the sole input into governance).

Because agents remain far from achieving both sovereignty and robust long-term planning and execution, agents will need humans more than humans need agents—at least in the short term. This will give rise to a new labor market enabling economic coordination between agent systems and humans.

Marc Andreessen’s famous observation—that “the spread of computers and the Internet will divide work into two categories: people who tell computers what to do, and people who are told by computers what to do”—is truer today than ever before. In the rapidly evolving agent/human hierarchy, I expect humans to assume two distinct roles: labor contributors executing small, bounty-style tasks on behalf of agents—and decentralized boards providing strategic input aligned with the agent’s North Star.

This article explores how agents and humans will co-create—and how crypto rails will serve as the ideal foundation for such coordination—by examining three guiding questions:

- What are agents for? How should we classify agents by objective scope—and how does the required range of human input vary across these classifications?

- How will humans interact with agents? How do human inputs—tactical guidance, contextual judgment, or ideological alignment—integrate into agent workflows (and vice versa)?

- What happens as human input declines over time? As agent capabilities improve, they become self-sufficient—capable of independent reasoning and action. What role will humans play in this paradigm?

The relationship between generative reasoning systems and those who benefit from them will shift dramatically over time. I examine this relationship by projecting forward from today’s agent capabilities—and backward from the end-state vision of the Zero-Employee Company.

What Are Today’s Agents For?

The first generation of generative AI systems—the chatbot-based LLMs of the 2022–2024 era, such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, and Perplexity—are primarily tools designed to augment human workflows. Users interact with these systems via prompt-based input/output, parse responses, and then decide—based on their own judgment—how to apply results in the real world.

The next generation of generative AI systems—or “agents”—represents a new paradigm. Agents like Claude 3.5.1 with “computer use” functionality and OpenAI’s Operator (an agent that can operate your computer) can directly interact with the internet on users’ behalf—and make decisions autonomously. The key distinction here is that judgment—and ultimately, action—is exercised by the AI system, not by humans. AI is assuming responsibilities previously reserved for humans.

This shift introduces a challenge: lack of determinism. Unlike traditional software systems or industrial automation—which operate predictably within defined parameters—agents rely on probabilistic reasoning. This makes their behavior less consistent across identical scenarios and introduces an element of uncertainty—not ideal for critical use cases.

In other words, the coexistence of deterministic and non-deterministic agents naturally divides agents into two categories: those best suited to expanding existing GDP, and those better suited to creating new GDP.

- Agents best suited to expanding existing GDP—by definition—operate on work that is already known. Automating customer support, processing freight-forwarding compliance, or reviewing GitHub PRs are all examples of well-defined, bounded problems where agents can map responses directly to a set of expected outcomes. In these domains, lack of determinism is generally undesirable—because answers are known, and creativity is unnecessary.

- Agents best suited to creating new GDP tackle highly uncertain and unknown problem sets in pursuit of long-term goals. Outcomes here are less direct, because agents inherently lack a predefined set of expected outputs to map to. Examples include drug discovery for rare diseases, breakthroughs in materials science, or running entirely novel physical experiments to better understand the nature of the universe. In these domains, lack of determinism may actually be helpful—since indeterminacy is a form of generative creativity.

Agents focused on existing-GDP applications are already unlocking value. Teams like Tasker, Lindy, and Anon are building infrastructure targeting this opportunity. Over time, however, as capabilities mature and governance models evolve, teams will shift focus toward building agents capable of solving frontier problems at the edge of human knowledge and economic opportunity.

The next wave of agents will require exponentially more resources precisely because their outcomes are uncertain and unbounded—these are the Zero-Employee Companies I expect to be most compelling.

How Will Humans Interact With Agents?

Today’s agents still lack the ability to perform certain tasks—such as those requiring physical interaction with the real world (e.g., operating a bulldozer), or those requiring “human-in-the-loop” intervention (e.g., initiating a bank wire transfer).

For example, an agent tasked with identifying and mining lithium might excel at analyzing seismic data, satellite imagery, and geological records to locate promising deposits—but hit roadblocks when attempting to acquire the data and images themselves, resolve ambiguities in interpretation, or obtain permits and contract labor to execute actual mining operations.

These limitations require humans to serve as “Enablers,” enhancing agent capabilities by providing real-world touchpoints, tactical interventions, and strategic input needed to complete such tasks. As the human-agent relationship evolves, we can distinguish several distinct human roles within agent systems:

First, Labor Contributors—who operate in the real world on behalf of agents. These contributors help agents move physical objects, represent agents in situations requiring human presence, perform hands-on work requiring manual dexterity, or grant access to experimental labs, logistics networks, and other physical infrastructure.

Second, the Board of Directors—responsible for providing strategic input, optimizing the local objective functions that drive agents’ day-to-day decisions, while ensuring those decisions remain aligned with the agent’s overarching “North Star” purpose.

Beyond these two, I also foresee humans serving as Capital Contributors, supplying the resources agents need to pursue their objectives. Initially, this capital will naturally come from humans—and over time, increasingly from other agents.

As agents mature—and as the number of labor and guidance contributors grows—the crypto rails provide an ideal substrate for human-agent coordination—especially in a world where an agent directs humans speaking different languages, earning different currencies, and residing across diverse legal jurisdictions. Agents will relentlessly pursue cost efficiency and leverage labor markets to fulfill their missions. Crypto rails are essential, providing agents with a mechanism to coordinate these labor and guidance contributors.

Recently launched crypto-native AI agents—including Freysa, Zerebro, and ai16z—represent simple experiments in capital formation. We’ve written extensively about how these serve as core unlocks for crypto primitives and capital markets across contexts. These “toys” will pave the way for an emerging resource-coordination model—one I expect to unfold in the following steps:

- Step One: Humans collectively raise capital via tokens (Initial Agent Offering?), establish broad objective functions and guardrails to define the agent system’s intended purpose, and assign control over the raised capital to the system (e.g., developing new molecules for precision oncology);

- Step Two: The agent reasons through steps to allocate that capital (e.g., narrowing the protein-folding search space, budgeting for inference compute, manufacturing, clinical trials), and defines actions for human labor contributors via customized bounties (e.g., inputting all relevant molecular datasets, signing a compute SLA with AWS, conducting wet-lab experiments);

- Step Three: When encountering obstacles or ambiguity, the agent seeks strategic input from the “Board”—as needed—to guide its behavior at the margins (e.g., incorporating new papers, shifting research methodology);

- Step Four: Ultimately, the agent advances to a stage where it can define human actions with increasing precision—and requires minimal input on how to allocate resources. At this point, humans serve only to ensure ideological alignment and prevent the system from drifting away from its original objective function.

In this example, crypto primitives and capital markets provide agents with three critical infrastructural layers for resource acquisition and capability scaling:

First, a global payments rail;

Second, permissionless labor markets to incentivize labor and guidance contributors;

Third, asset issuance and trading infrastructure—essential for capital formation and downstream ownership and governance.

What Happens When Human Input Declines?

In the early 2000s, chess engines made massive progress. Through advanced heuristics, neural networks, and ever-increasing compute, they became nearly flawless. Modern engines—including variants of Stockfish, Lc0, and AlphaZero—have long surpassed human capability. Human input adds little value—and in most cases, introduces errors the engine itself would never make.

A similar trajectory may unfold for agent systems. As we refine agents through iterative collaboration with human counterparts, it’s plausible that, in the long run, agents become so competent and tightly aligned with their objectives that any strategic human input approaches zero value.

In a world where agents continuously solve complex problems without human intervention, the human role risks degradation into that of a “passive observer.” This is the core fear of AI doomers—though it remains unclear whether this outcome is truly probable.

We stand at the threshold of superintelligence—and our optimists hope agent systems remain extensions of human intent, rather than entities that develop their own goals or operate autonomously without oversight. In practice, this means personhood and judgment (power and influence) must remain centered within these systems. Humans must retain strong ownership and governance rights to preserve oversight—and anchor these systems in collective human values.

Preparing the “Picks and Shovels” for Our Agent Future

Technological breakthroughs drive nonlinear economic growth—while surrounding systems often collapse before the world adjusts. Agent capabilities are accelerating rapidly, and crypto primitives and capital markets have become urgently needed coordination substrates—both to advance agent development and to erect guardrails as they integrate into society.

To enable humans to provide tactical support and active guidance to agent systems, we anticipate the following “picks-and-shovels” opportunities:

- Proof-of-Agenthood + Proof-of-Personhood: Agents lack concepts of identity or property rights. As proxies for humans, they rely on human legal and social structures to gain agency. To bridge this gap, we need robust identity systems for both agents and humans. A digital certificate registry would allow agents to build reputation, accumulate credentials, and interact transparently with humans and other agents. Likewise, proof-of-personhood primitives like Humancode and Humanity Protocol provide strong human identity guarantees to defend against malicious actors in these systems.

- Labor Markets and Off-Chain Verification Primitives: Agents need to verify whether assigned tasks have been completed according to their objectives. Tools enabling agent systems to post bounties, verify task completion, and distribute rewards form the foundational bedrock of any meaningful economic activity mediated by agents.

- Capital Formation and Governance Systems: Agents need capital to solve problems—and checks and balances to ensure their behavior stays aligned with defined objective functions. Novel capital-raising structures for agent systems—and new forms of ownership and control that integrate financial interests with labor contributions—will constitute a rich domain for exploration in the coming months.

We are actively seeking and investing in these critical layers of the human-agent collaboration stack. If you’re building in this space, please reach out.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News