Visa effect

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Visa effect

Today, stablecoins are facing the same fragmentation issue, and the solution might be exactly what Visa did fifty years ago.

Author: Nishil Jain

Translation: Block unicorn

Introduction

In the 1960s, the credit card industry was chaotic. Banks across the United States were trying to build their own payment networks, but each operated in isolation. If you held a Bank of America credit card, you could only use it at merchants that had agreements with Bank of America. When banks tried to expand beyond their own networks, they faced major interbank settlement challenges for every credit card transaction.

If a merchant accepted cards issued by another bank, transactions had to be settled through existing check-clearing systems. The more banks that joined, the greater the settlement complexity became.

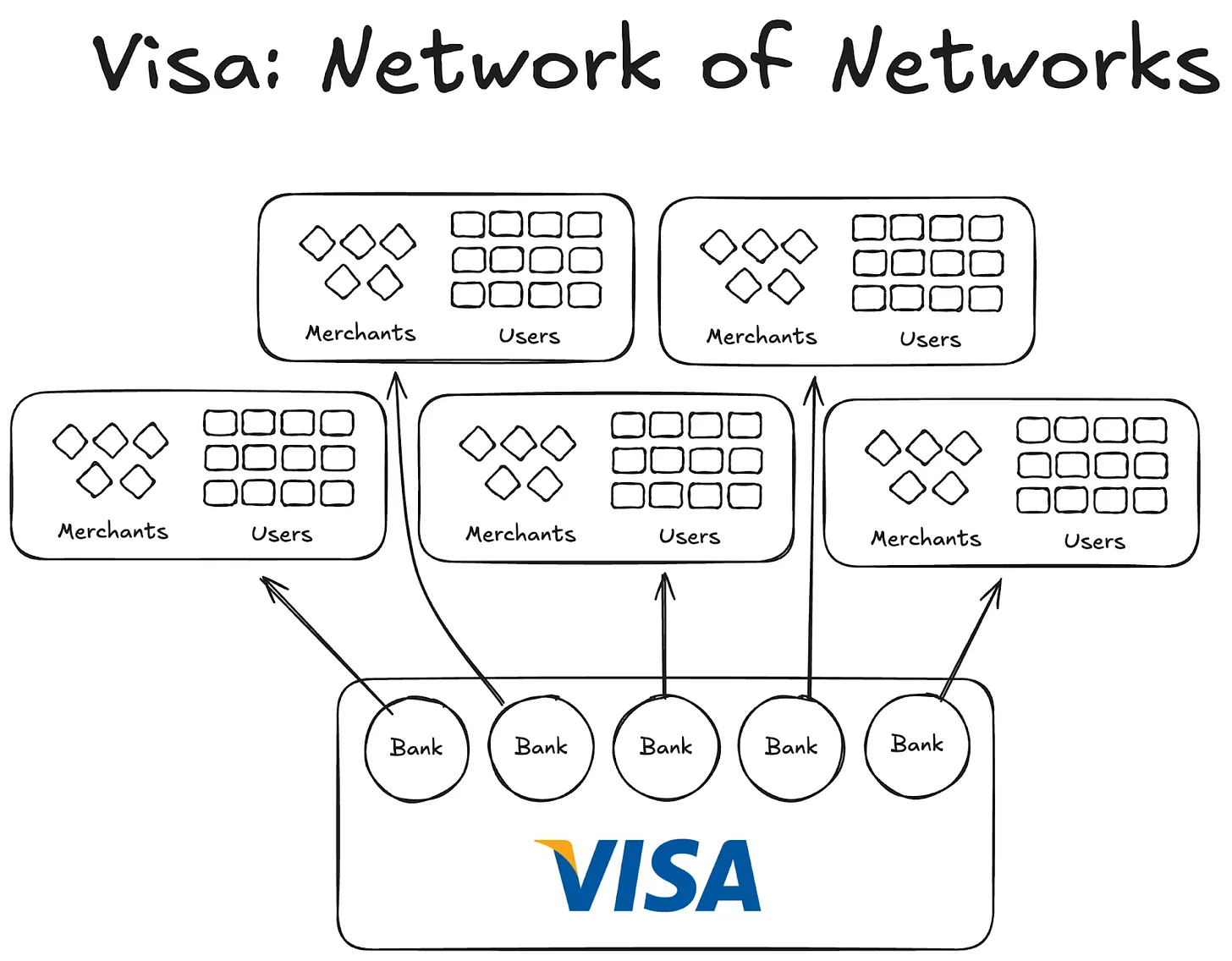

Then Visa emerged. While its technological innovations undoubtedly played a significant role in revolutionizing card payments, its greater achievement lay in global universality and its success in bringing banks worldwide into a unified network. Today, nearly every bank on the planet is part of the Visa network.

Though this seems normal today, imagine the scale of convincing the first thousand banks—both within and outside the U.S.—that joining a cooperative agreement was smarter than building their own networks, and you begin to grasp the magnitude of what was accomplished.

By 1980, Visa had become the dominant payment network, processing around 60% of all credit card transactions in the U.S. Today, Visa operates in over 200 countries.

The key wasn't superior technology or deeper pockets—it was structure: a model capable of aligning incentives, distributing ownership, and generating compounding network effects.

Today, stablecoins face a similar fragmentation problem. And the solution may lie in doing exactly what Visa did half a century ago.

Experiments Before Visa

Other companies that existed before Visa failed to scale.

American Express (AMEX) attempted to grow its credit card business as an independent bank, but its expansion relied solely on signing up new merchants and users one by one. In contrast, BankAmericard worked differently—Bank of America owned the credit card network, while other banks leveraged its network effects and brand value.

American Express had to individually recruit each merchant and user to open accounts with them; Visa, however, scaled by onboarding entire banks. Every bank joining Visa’s cooperative network instantly gained access to thousands of new customers and hundreds of new merchants.

On the other hand, BankAmericard struggled with infrastructure. They lacked an efficient system for settling credit card transactions from a consumer’s bank account to a merchant’s bank account. There was no effective interbank settlement mechanism in place.

As more banks joined, the problem worsened. Thus, Visa was born.

Four Pillars of Visa's Network Effects

From Visa’s story, we can identify two to three critical factors behind its cumulative network effects:

Visa benefited from being an independent third party. To ensure no bank felt threatened by competition, Visa was structured as a cooperative, independent organization. Visa itself didn’t compete for distribution; the banks did.

This incentivized banks to actively promote the network to capture larger profit shares. Each bank earned a portion of total profits proportional to its share of total transaction volume processed.

Banks had a voice in shaping network functionality. Rules and changes at Visa required voting by member banks, with 80% approval needed for any proposal to pass.

Visa had exclusivity clauses with each bank—at least initially. Any bank joining the cooperative could only issue Visa cards and use the Visa network, not join competing networks. Therefore, to interact with Visa banks, others also had to become part of the same ecosystem.

When Visa’s founder, Dee Hock, traveled across the U.S. persuading banks to join, he had to convince each one that joining Visa was more advantageous than building their own network.

He explained that joining Visa meant more users and merchants would connect to the same network, enabling more digital transactions globally and increasing returns for everyone involved. He also emphasized that if they built their own isolated network, their user base would remain extremely limited.

Implications for Stablecoins

In a sense, Anchorage Digital and other companies now offering "stablecoin-as-a-service" are replaying the BankAmericard story in the stablecoin space. They provide the underlying infrastructure for new issuers to launch stablecoins, but liquidity keeps fragmenting across new tokens.

Currently, Defillama lists over 300 stablecoins. And each newly created stablecoin is confined to its own ecosystem. As a result, no single stablecoin can achieve the network effects necessary for mainstream adoption.

If these new coins are backed by the same underlying assets, why do we need more tokens with different codebases?

In our Visa analogy, these resemble BankAmericards. Ethena, Anchorage Digital, M0, or Bridge—all allow protocols to issue their own branded stablecoins, but this only deepens ecosystem fragmentation.

Ethena is another such protocol enabling yield pass-through and white-label customization of its stablecoin. Just like MegaETH issuing USDm—they used tools supporting USDtb to mint USDm.

Yet this model fails. It merely fragments the ecosystem further.

In the credit card case, brand differences between banks didn’t matter because they caused no friction in user-to-merchant payments. The underlying issuance and payment layer was always Visa.

But for stablecoins, this isn't true. Different token codes mean infinitely fragmented liquidity pools.

Merchants—or in this context, applications or protocols—won’t add every stablecoin issued by M0 or Bridge to their accepted list. Acceptance depends on public market liquidity; coins with the largest holder bases and deepest liquidity will naturally be preferred, while others will be excluded.

The Path Forward: A Visa Model for Stablecoins

We need independent third-party institutions to manage stablecoins across different asset classes. Issuers and applications backing these assets should be able to join a cooperative, gaining access to reserve yields. At the same time, they should hold governance rights, allowing them to vote on the development path of their chosen stablecoin.

From a network effects perspective, this would be a superior model. As more issuers and protocols adopt the same token, it enables widespread usage of a single token that retains value internally rather than leaking profits to external parties.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News