Bitcoin's Duplicate Transactions: An Interesting Bug with Minimal Risk

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Bitcoin's Duplicate Transactions: An Interesting Bug with Minimal Risk

Duplicate transactions can cause confusion, and Bitcoin developers have been fighting against them in various ways for years.

Overview

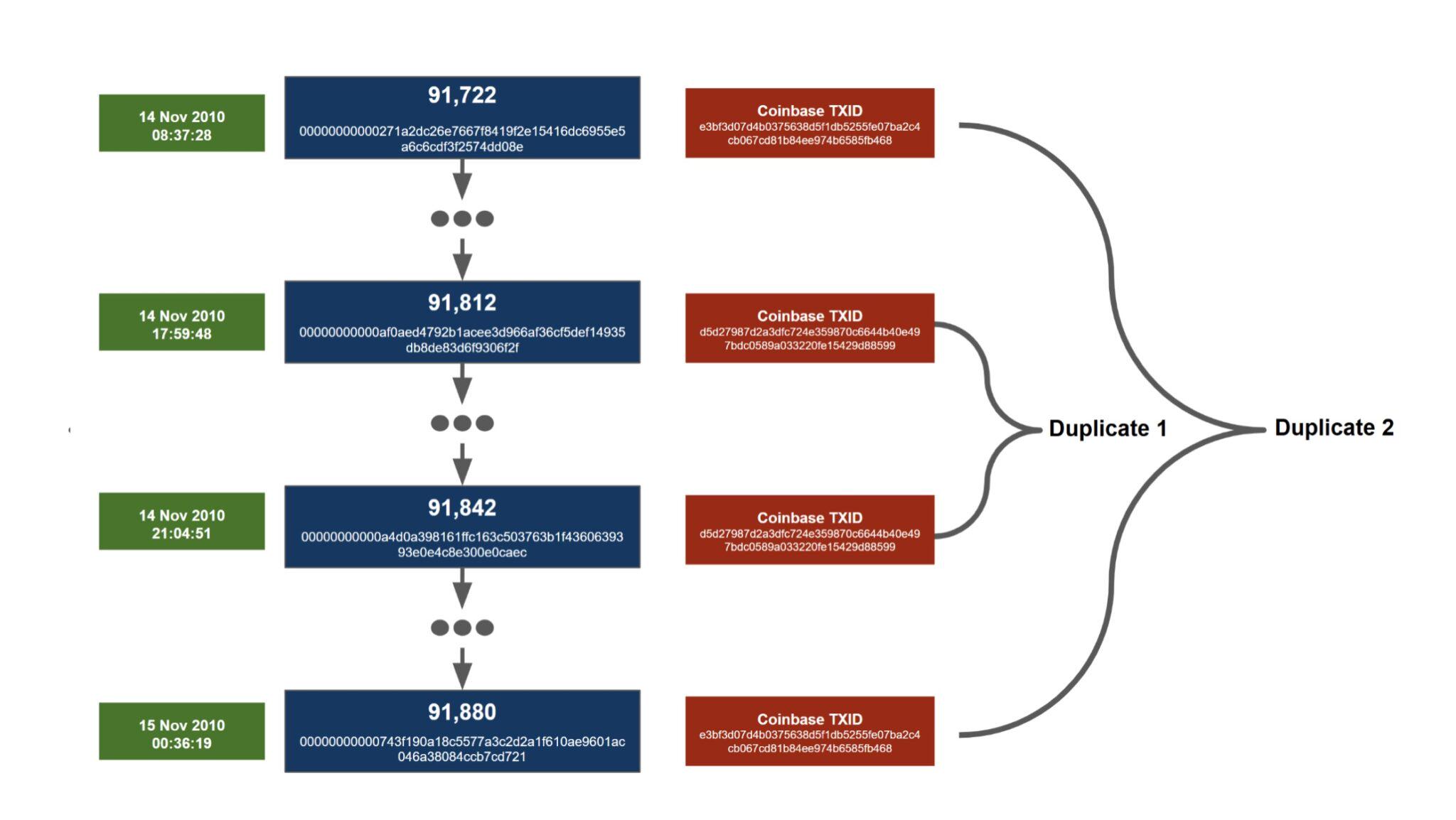

A normal Bitcoin transaction spends at least one output from a previous transaction by referencing its transaction ID (TXID). These unspent outputs can only be spent once; if they could be spent twice, you could perform double-spends on Bitcoin, rendering it worthless. However, there are in fact exactly two pairs of completely identical transactions in Bitcoin. This situation is possible because coinbase transactions have no transaction inputs—they generate new coins instead. Therefore, two different coinbase transactions might send the same amount to the same address and be constructed identically, making them fully identical. Since the transactions are identical, their TXIDs also match, as TXID is the hash digest of the transaction data. The only other way for a TXID to be duplicated would be through a hash collision, which for cryptographically secure hash functions like SHA256 is considered highly improbable and practically impossible. No such SHA256 collision has ever occurred in Bitcoin or anywhere else.

Both sets of duplicate transactions occurred within a close timeframe—between November 14, 2010, 08:37 UTC and November 15, 2010, 00:38 UTC, spanning about 16 hours. The first pair of duplicates is embedded between the two instances of the second pair. We classify d5d2….8599 as the first duplicate transaction because it became duplicated first, even though curiously it appears earlier on the blockchain after the other duplicate transaction e3bf….b468.

Duplicate Transaction Details

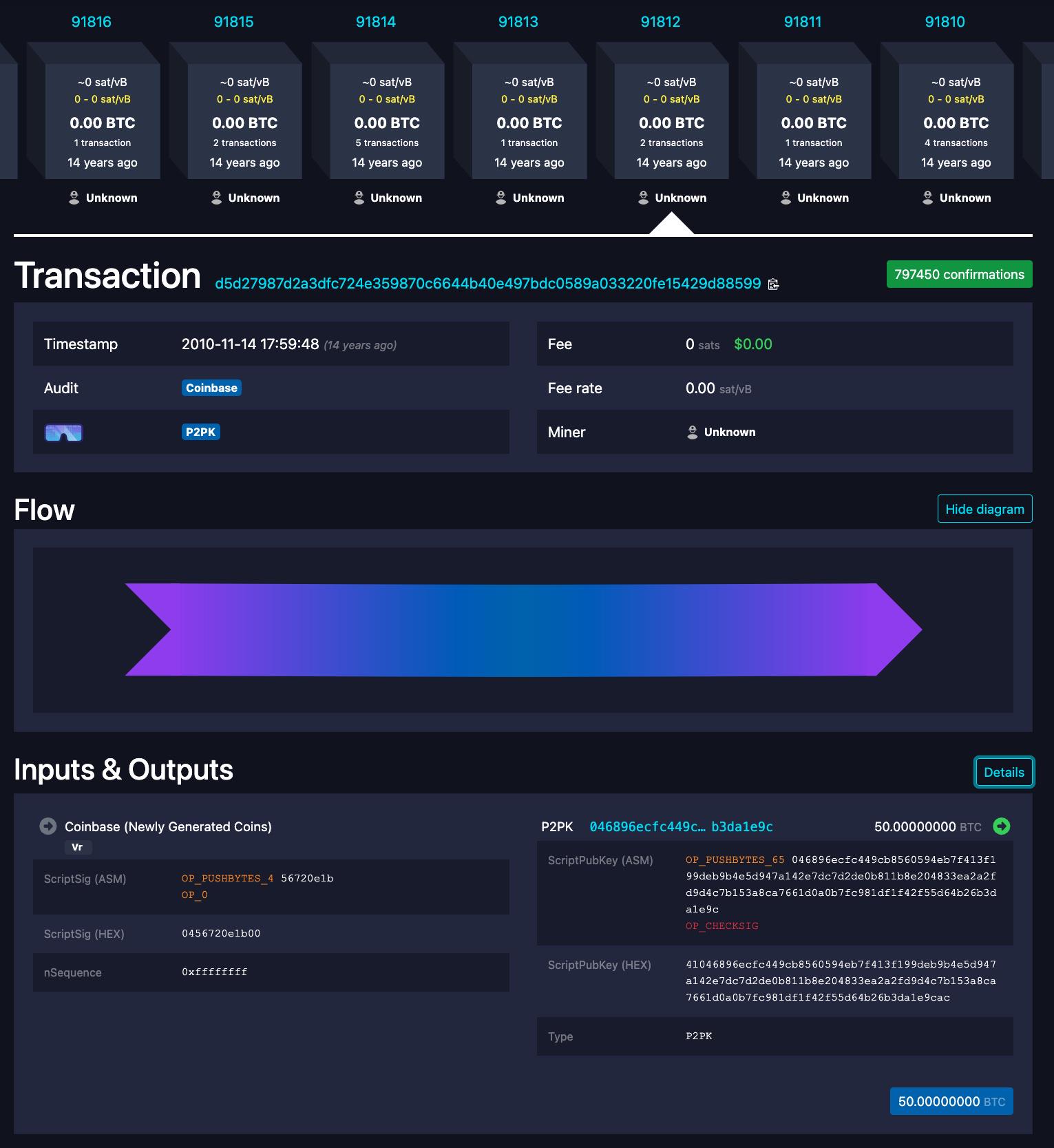

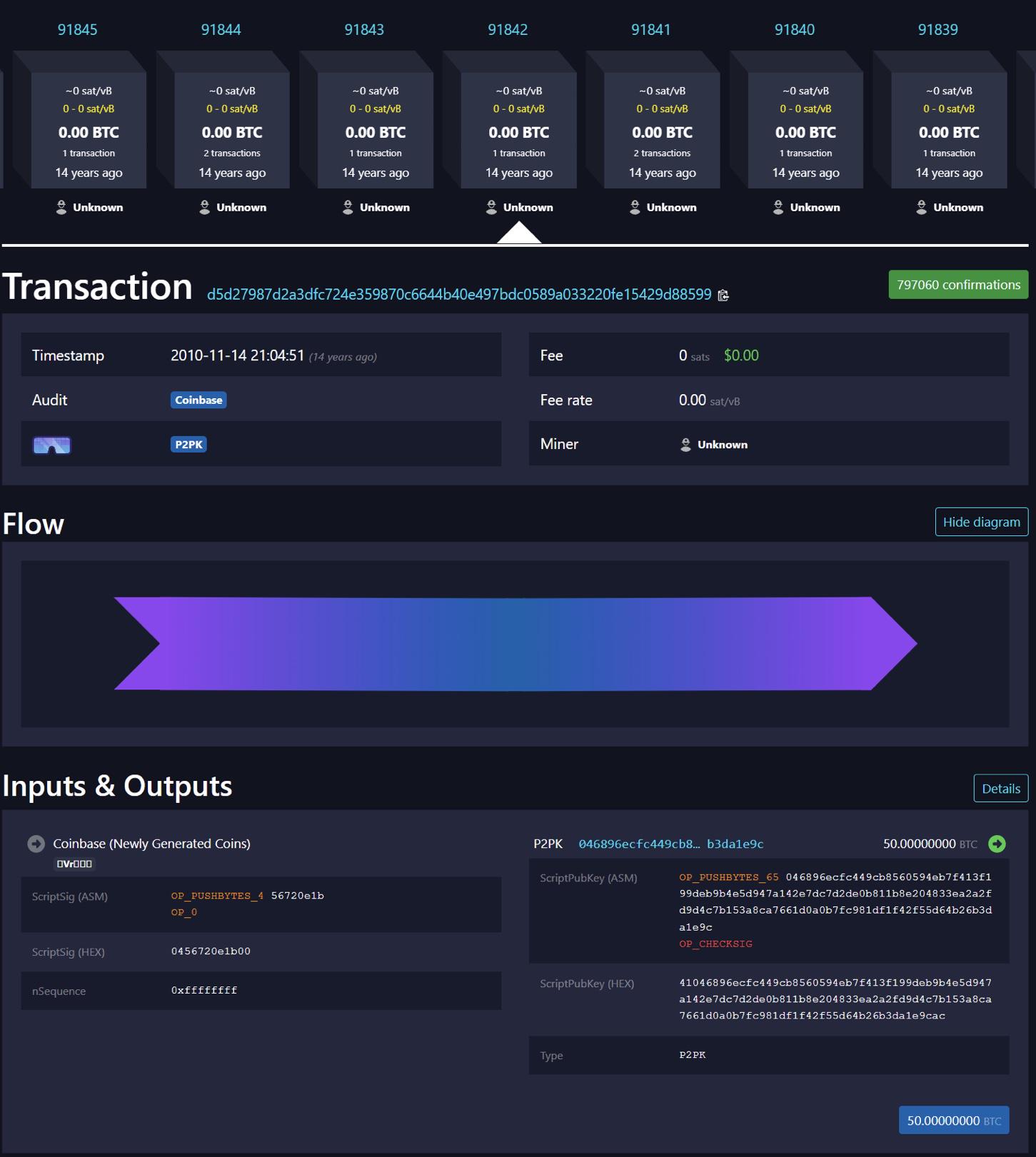

In the images below, two screenshots from the mempool.space block explorer show the first duplicate transaction appearing in two different blocks.

Interestingly, when entering the relevant URLs into a web browser, the mempool.space block explorer by default displays the earlier block for d5d2….8599, but shows the later block for e3bf….b468. Blockstream.info and Btcscan.org behave identically to mempool.space. In contrast, based on our basic testing, Blockchain.com and Blockchair.com behave differently, always displaying the latest version of a duplicated transaction when the URL is entered into the browser.

Of the four related blocks, only one block (block 91,812) contains additional transactions. This transaction merged outputs of 1 BTC and 19 BTC into a single 20 BTC output.

Can These Outputs Be Spent?

The existence of two pairs of identical TXIDs creates referencing issues for subsequent transactions. Each duplicate transaction is worth 50 BTC. Thus, these duplicate transactions involve either 4 × 50 BTC = 200 BTC total, or alternatively 2 × 50 BTC = 100 BTC depending on interpretation. In effect, 100 BTC technically do not exist. As of today, all 200 BTC remain unspent. To the best of our knowledge (though we may be mistaken here), if someone possesses the private keys associated with these outputs, they could spend the bitcoins. However, once spent, the UTXO would be removed from the database, causing the duplicate 50 BTC to become unspendable and lost—meaning only 100 BTC could potentially be recovered. As for whether such a spend would draw from the earlier or the later block, this may be undefined or indeterminable.

An individual could have spent all the bitcoins before creating the duplicate transactions, then created duplicate outputs, adding new entries into the unspent output database. This would mean not only duplicate transactions but potentially duplicate copies of already-spent outputs. If this happened, spending those outputs could generate further duplicate transactions, creating a chain of duplication. One would need to carefully manage the sequence of events—always spending before creating duplicates—or else bitcoins could be permanently lost. These new duplicate transactions would not be coinbase transactions, but "normal" transactions. Fortunately, this scenario has never occurred.

Problems Caused by Duplicate Transactions

Duplicate transactions are clearly undesirable. They create confusion for wallets and block explorers and make it unclear where bitcoins originate. They also open doors to various attacks and vulnerabilities. For example, you could pay someone using two duplicate transactions. When the recipient attempts to use the funds, they might discover only half the money is recoverable. This could be used in an attack against an exchange, attempting to bankrupt it while the attacker suffers no loss, since they could immediately withdraw funds after depositing them.

Banning Transactions with Duplicate TXIDs

To mitigate the issue of duplicate transactions, in February 2012, Bitcoin developer Pieter Wuille proposed BIP30, a soft fork that prohibits transactions with duplicate TXIDs unless the prior TXID has already been spent. This soft fork applies to all blocks created after March 15, 2012.

In September 2012, Bitcoin developer Greg Maxwell modified the rule so that BIP30 checks apply to all blocks, not just those after March 15, 2012—with the exception of the two duplicate transactions mentioned earlier. This fixed certain denial-of-service (DoS) vulnerabilities. Technically, this was another soft fork, although the rule change applied only to blocks older than six months, thus carrying none of the risks normally associated with protocol changes.

The BIP30 check is computationally expensive. Nodes must examine all transaction outputs in a new block and verify whether those output endpoints already exist in the UTXO set. This high cost may explain why Wuille originally limited the check only to unspent outputs—if applied to all outputs, the computation would be even more intensive and incompatible with pruning.

BIP34

In July 2012, Bitcoin developer Gavin Andresen proposed BIP34, a soft fork activated in March 2013. This protocol change requires coinbase transactions to include the block height, enabling better block version management. The block height is added as the first item in the coinbase scriptSig. The first byte of the coinbase scriptSig indicates how many bytes are used for the block height number, followed by the bytes representing the height itself. For the first c160 years (223 / (144 blocks per day × 365 days per year)), the first byte should be 0x03. This is why modern coinbase scriptSigs (in HEX) always start with 03. This soft fork appears to have fully resolved the duplicate transaction issue, ensuring all transactions are now unique.

Since BIP34 has been adopted, in November 2015, Bitcoin developer Alex Morcos submitted a pull request to the Bitcoin Core repository, removing the need for nodes to perform BIP30 checks. After all, since BIP34 fixed the root cause, the expensive BIP30 check was no longer necessary. Although not realized at the time, this change technically constituted a hard fork for a few extremely rare future blocks. However, the potential hard fork is now considered irrelevant, as almost no one runs node software from before November 2015. On forkmonitor.info, we run Bitcoin Core 0.10.3, released in October 2015. This represents a pre-hard-fork state where clients still perform the costly BIP30 check.

The Block 983,702 Issue

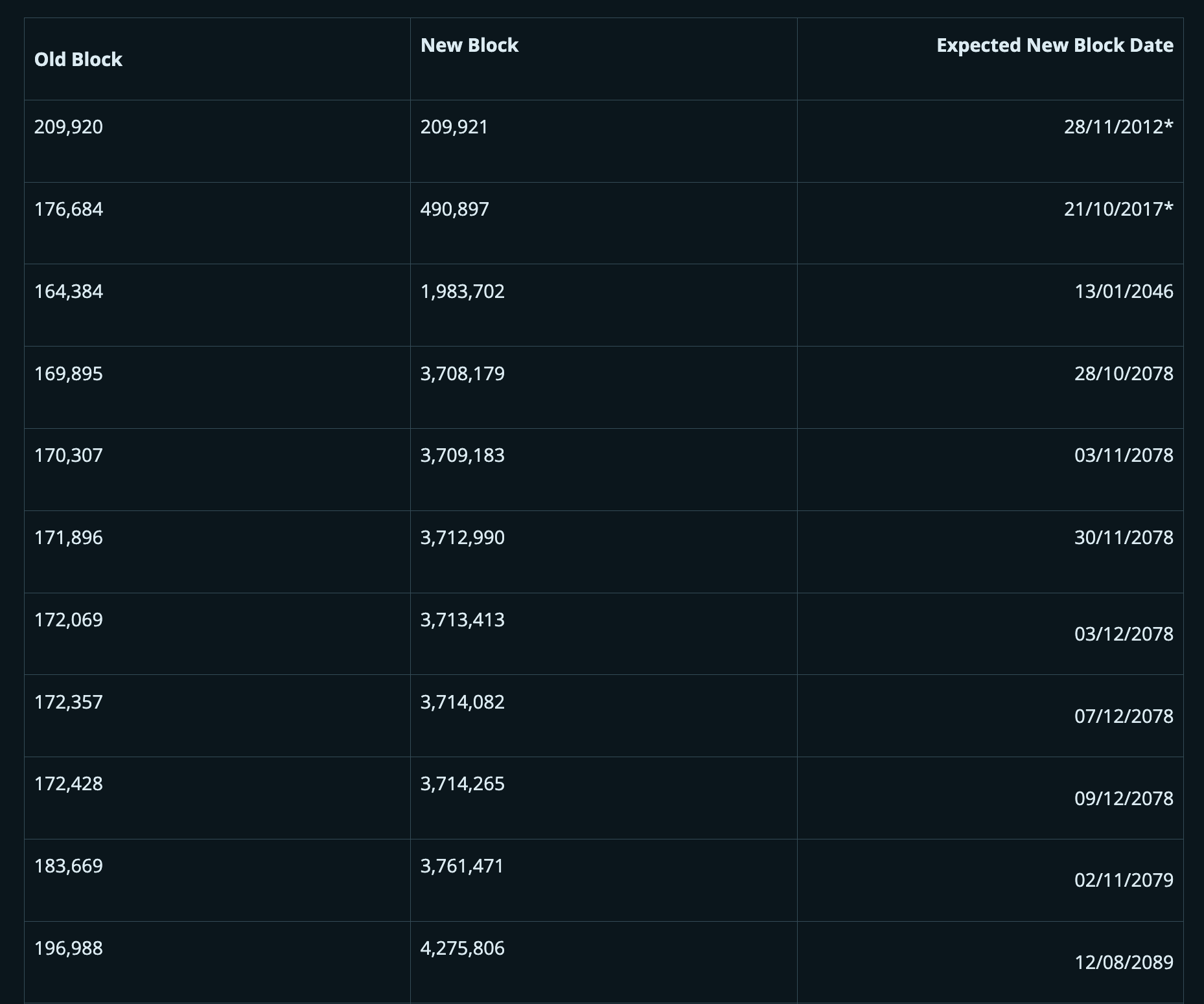

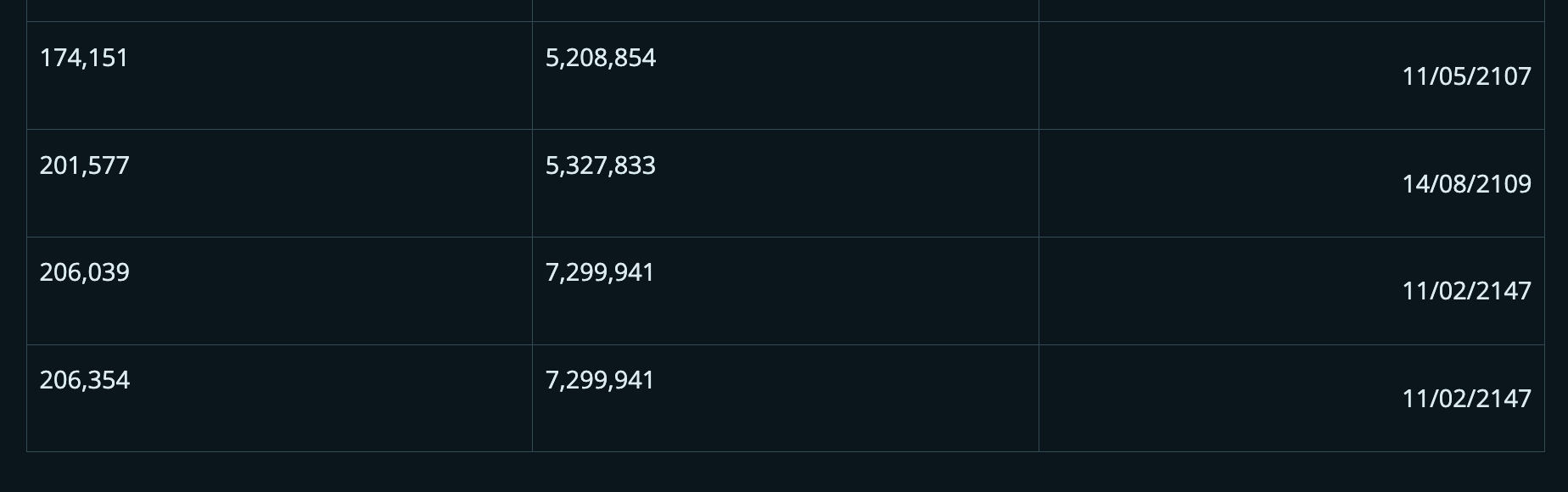

It turns out that some coinbase transactions in blocks prior to BIP34 activation used scriptSigs whose first byte coincidentally matches valid future block heights. Therefore, while BIP34 indeed fixed the problem in nearly all cases, it was not a complete 100% fix. In 2018, Bitcoin developer John Newbery printed out the full list of potentially duplicatable blocks, shown in the table below.

*Note: Coinbase transactions from these blocks were not actually duplicated in 2012 and 2017. Block 209,921 (just 79 blocks before the first halving) cannot be duplicated because BIP30 was enforced during that period.

Source: https://gist.github.com/jnewbery/df0a98f3d2fea52e487001bf2b9ef1fd

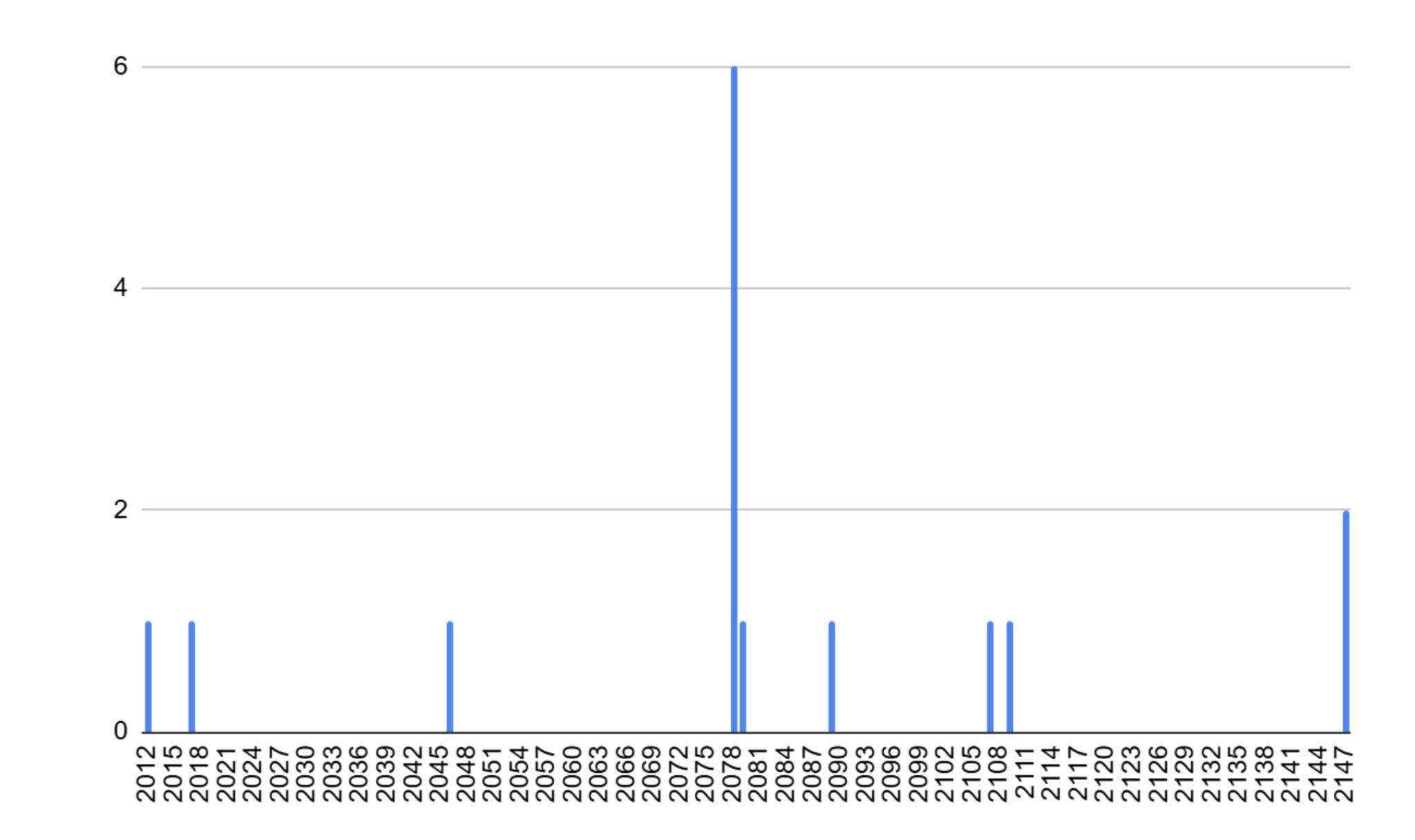

Potential Duplicate Coinbase Transactions by Year

Source: https://gist.github.com/jnewbery/df0a98f3d2fea52e487001bf2b9ef1fd

Thus, the next block where a duplicate transaction could occur is block 1,983,702, expected to be mined around January 2046. The coinbase transaction from block 164,384, mined in January 2012, sent 170 BTC across seven different output addresses. Therefore, if a miner in 2046 wanted to carry out this attack, they would not only need to be lucky enough to find this specific block, but also burn fees totaling less than 170 BTC, with the total cost slightly exceeding 170 BTC including the opportunity cost of the 0.09765625 BTC block subsidy. At the current Bitcoin price of $88,500, this would cost over $15 million. It remains unknown who owns the seven addresses from the 2012 coinbase transaction; the keys are likely long lost. Currently, all seven output addresses from this coinbase transaction have been spent, with three being spent in the same transaction. We suspect these funds may be linked to the Pirate40 Ponzi scheme, though this is purely speculative. Therefore, this attack appears not only extremely costly but also nearly useless to any attacker. Spending millions just to hard-fork out 2015-era nodes from 31 years ago seems impractical.

The next vulnerable block susceptible to duplication is block 169,985 from March 2012. This coinbase spent just over 50 BTC, significantly less than 170 BTC. Of course, 50 BTC was the subsidy at the time; by 2078, when this coinbase becomes vulnerable to duplication, the subsidy will be much lower. To exploit this, a miner would need to burn approximately 50 BTC in fees—fees they cannot recover, as they must be sent to old 2012 outputs. No one knows what Bitcoin’s price will be in 2078, but the cost of such an attack could still be prohibitively high. Therefore, while this issue may not represent a major risk to Bitcoin, it remains a curious concern.

Since the SegWit upgrade in 2017, coinbase transactions can also include commitments to all transactions in a block. These pre-BIP34 blocks do not contain witness commitments. Therefore, to produce a duplicate coinbase transaction, a miner would need to exclude any SegWit output redemption transactions from the block, further increasing the opportunity cost of the attack, as the block might miss out on many fee-paying transactions.

Conclusion

Given the difficulty and high cost of replicating transactions, along with the extreme rarity of exploitable conditions, the duplicate transaction vulnerability does not appear to be a major security threat to Bitcoin. Still, considering the vast timescales involved and the novelty of duplicate transactions, it remains an intriguing topic. Nonetheless, developers have spent considerable effort addressing this issue over the years, and the year 2046 may serve as a de facto deadline in some developers’ minds to finally resolve it. There are multiple ways to fix this bug, possibly requiring a soft fork. One potential solution is to enforce witness commitments universally.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News