Yang Bin Legend: The Former Chinese Wealthiest Man and Honorary Son of Kim Jong-il Arrested for Crypto Fraud

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Yang Bin Legend: The Former Chinese Wealthiest Man and Honorary Son of Kim Jong-il Arrested for Crypto Fraud

The legendary "dark horse billionaire" famous for his bare-knuckle swindling tactics, who pivoted to blockchain after being released from prison, has fallen once again.

By Jaleel Jia Liu, BlockBeats

On August 26, 2024, Yang Bin, once China’s second-richest man, sat in the defendant's dock at Singapore’s High Court. Usually dark-complexioned, Yang appeared unwell. Through a court interpreter, he informed the judge that he was suffering from stomach cancer.

Silence filled the courtroom as the judge read out the verdict. Yang Bin was sentenced to six years in prison and fined 16,000 Singapore dollars for orchestrating a multi-million-dollar cryptocurrency Ponzi scheme under the guise of A&A Blockchain Innovation.

The case traces back to 2021, when Yang used the name A&A Blockchain Innovation to attract numerous investors, claiming ownership of 300,000 cryptocurrency mining machines and promising daily returns of 0.5%. In reality, no such mining equipment existed. Instead, Yang paid early investors with funds from new ones—a classic Ponzi scheme. Eventually, Singaporean regulators uncovered the fraud entirely.

This wasn’t Yang’s first legal reckoning. In 2003, a Chinese court sentenced him to 18 years in prison. “Mandela was imprisoned for 27 years and became president afterward. I’ll serve 18 years, emerge at age 58, and still become president,” he boasted defiantly, even as a 68-page judgment failed to dampen his arrogance.

A former self-proclaimed "China's richest man" and leader of a special administrative zone in North Korea, Yang built a business empire fueled by ambition and glory—and lived a life of dramatic contrasts: from orphan to billionaire, from corporate titan to convict. What follows is the full truth behind this once-celebrated “dark horse tycoon.”

Yang Bin lighting a cigarette for Kim Yong-nam, North Korea’s number two official

From Orphan to Tycoon: The Wealth Legend of Yang Bin

Yang Bin’s business saga began in poverty but unfolded with theatrical flair. An orphan from a humble background, he gained admission to a naval academy and remained there as a teacher thanks to strong academic performance. Yet Yang was never satisfied. At 25, he left for the Netherlands, launching an extraordinary international business adventure.

In the Netherlands, Yang used $10,000 earned from odd jobs to start cross-border trade, quickly identifying market opportunities between China and Eastern Europe. He rose rapidly in the textile and apparel import-export sector, amassing $20 million within just two years—his first major fortune.

Soon after, Yang turned his attention back to China. Amid the country’s reform and opening-up era, he launched a greenhouse agriculture project called “Dutch Village,” quickly emerging as a leader in agricultural industry. Leveraging his foreign investor status, he secured extensive tax exemptions and government support, enabling rapid expansion of his enterprise.

Buildings at Dutch Village

But it was Yang’s successful listing of Eurasia Agriculture on Hong Kong’s stock market in 2001 that truly catapulted him to fame. The move brought massive capital inflows and vaulted Yang into the upper echelons of China’s rich list, earning him recognition as a breakout “dark horse tycoon.”

“Merchants who excel should enter politics,” Yang believed. On September 24, 2002, he secured the position of Chief Executive of the Sinuiju Special Administrative Region in North Korea—a role akin to Hong Kong’s Chief Executive. At a press conference, he boldly declared to reporters: “I am the adopted son of Mr. Kim Jong-il.”

Yang Bin’s Mastery of “Empty-Handed Wolf” Tactics

Yet, the day before he was set to assume office in North Korea, police surrounded his villa. Alongside his security guards and two guard dogs, Yang was taken from Dutch Village and placed under investigation. By July the following year, he had been convicted on multiple charges and sentenced to 18 years in prison.

Only then did the public realize Yang Bin was a master con artist—one exceptionally skilled at pulling off grand illusions through sleight of hand.

The most sophisticated scams aren’t built purely on fiction; they weave truth and lies so seamlessly that distinction becomes impossible. Why was Yang able to rise to the top through deception? Largely because parts of his story were indeed true.

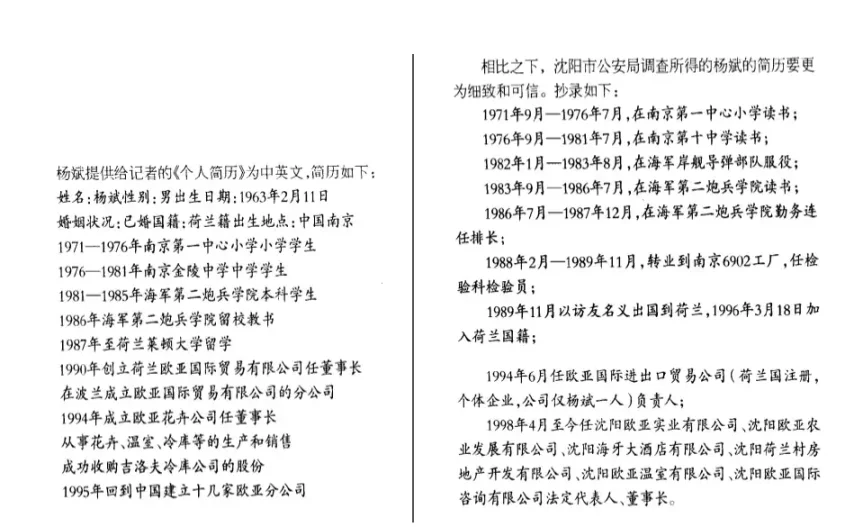

According to Yang’s own narrative: born in Nanjing in 1963, orphaned at five; entered the Second Artillery Corps Academy at 18 and stayed on as faculty; studied in the Netherlands at 24, acquiring Dutch citizenship; founded his own company at 27, engaging in clothing and textile trade. This modern-day version of *Oliver Twist* formed the carefully crafted public image Yang cultivated. But the reality was far different.

An in-depth investigation by Shenyang Public Security Bureau gradually exposed Yang’s fabricated resume. Contrary to claims, he didn’t directly enroll in military school but was drafted from Nanjing and sent there, attending a junior college rather than earning a bachelor’s degree. After graduation, he served not as faculty but as a maintenance soldier.

Different versions of Yang Bin’s resume obtained by journalist Wang Yude from Yang himself and police records

Later, Yang transitioned to working in a factory. There, he met a Dutch woman and left China under the pretense of visiting her, eventually overstaying in the Netherlands. Although he enrolled in Leiden University’s economics program, he never completed his studies.

Xu Hongjiong, a computer programming student in the Netherlands who once visited Yang’s home, said Yang never attended university. According to Xu, Yang barely spoke Dutch and lacked financial knowledge. His acquisition of Dutch citizenship was also questionable. Multiple insiders revealed Yang obtained it through deception and falsified documents.

Further scrutiny casts doubt on the legitimacy of Yang’s “first fortune.” He claimed to have seized market opportunities after Eastern Europe’s collapse, rapidly accumulating $20 million through trade between China and Poland. However, sources in the Netherlands say Yang made little money from international trade in the early 1990s and instead relied on welfare benefits applied for by his wife, Pan Chaorong, and their children to survive.

“Impossible, impossible—it must be a mistake,” said friends and acquaintances in the Netherlands when news of Yang’s $20 million fortune circulated. “The Chinese community in the Netherlands is small. Anyone who starts a company or makes big money becomes known quickly.”

A Chinese restaurant owner who knew Yang for over a decade revealed they partnered on minor ventures between 1991 and 1992, all extremely limited in scale—far from the millions Yang claimed. Even by 1992, when Yang registered two small companies, their size equaled only modest private enterprises in China. “It’s certain that by 1992, Yang Bin absolutely did not have $20 million,” the man said.

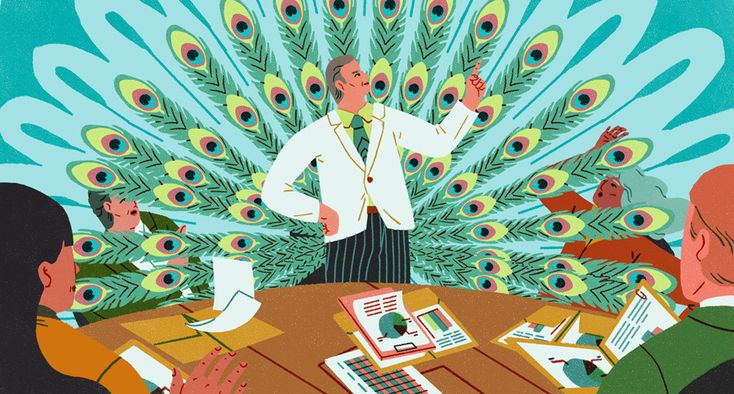

A Genius Merchant and Charismatic Speaker With Keen Instincts

Though infamous for fraud, deception alone cannot explain Yang’s rapid wealth accumulation and widespread influence. In fact, he possessed remarkable business acumen, skillful capital operations, and an ability to adapt—leveraging financial tools, capital markets, and government policy advantages.

Some media claimed Yang couldn’t speak English at all—but this is inaccurate. Reporters witnessed him conversing in English with a foreign friend outside his office, albeit with a heavy accent. Those close to him noted that despite his military academy background, he showed little interest in military affairs. Instead, he genuinely loved learning English and studying Dutch agriculture.

“The Netherlands accounts for 73% of global flower exports and is famously known as ‘Europe’s vegetable basket,’ supplying 67% of Europe’s vegetables. The world has three major agricultural models: highly mechanized U.S. farming, Israel’s drip irrigation system, and the classic Dutch model.” This was reportedly one of Yang’s go-to opening lines.

Yang Bin inspecting Dutch Village

Leveraging passion and powerful rhetoric, Yang convinced everyone that Dutch Village would not only thrive agriculturally but also become a tourist destination complete with Disney and Universal Studios, indoor tropical rainforests, seaside amusement parks—the world’s largest indoor beach.

“Japan demands 1 trillion RMB worth of vegetables annually, plus another 1.5 trillion RMB in other food products. Capturing just one-third of that market would yield annual profits exceeding 750 billion RMB,” Yang proclaimed—clearly adept at selling visions and future prospects. Shenyang authorities invited him to establish a base and branch offices, offering land and tax incentives.

Thus, on December 18, 1997, Eurasia Group established its headquarters in Shenyang, later selling off seven or eight nationwide branches. Once granted land, Yang began demonstrating his mastery of capital markets.

Loans were a primary funding source. Yang secured a massive 400 million yuan loan from the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and another 30 million yuan from the Agricultural Bank of China. He also raised funds via the stock market, primarily through asset restructuring and high-ratio share bonuses. These maneuvers generated enormous returns.

Additionally, Yang excelled at talent management, appointing Yan Chuang, an accounting graduate, as director, vice president, and vice chairman of the board. Yan became not only Yang’s right-hand man but also the chief architect and executor behind Eurasia Agriculture’s Hong Kong IPO.

On July 19, 2001, Yang successfully listed “Eurasia Agriculture” in Hong Kong, raising 700 million HKD—one of the biggest winners among mainland firms going public in Hong Kong that year. With 72.3% ownership, Yang’s stake was valued at nearly 1.8 billion HKD.

But the toll was visible. He devoted virtually every waking hour to work. His pace intensified—donors, journalists, foreign investors constantly sought meetings or called him. He chain-smoked, one cigarette after another, often complaining of exhaustion. Everyone who saw him remarked how aged he looked—far older than his 38 years.

Jinzhou Prison

Even behind bars, Yang refused to rest, continuing to exercise his business talents.

“Those with connections would send written requests, faxed into the prison for Yang to approve. Only with Yang’s signature could you buy property,” revealed buyers at the time. Despite imprisonment, Yang remotely controlled real estate sales. Demand was so high that ordinary people without connections couldn’t purchase homes.

The prison was only 20 kilometers from Dutch Village. Rumor had it Yang returned almost weekly under “medical parole” to manage company affairs. Typically on Thursdays or Saturdays, he’d drive his stretch Mercedes from prison to Dutch Village. He even helped develop an “industrial park around the prison,” collaborating on projects like plastic-steel window factories, color-coated steel plants, and greenhouse agriculture.

Thus, Yang enjoyed “premium prisoner” privileges. One insider said a deputy director oversaw him personally. While he previously smoked four packs a day, now he limited himself to one pack (30 packs monthly). A prison doctor monitored his health. His family delivered his favorite braised pork three times a week, and staff from the Dutch embassy visited monthly, bringing requested items.

Fraud Upgraded: Post-Prison Pivot to Blockchain

In traditional business, Yang used loans and IPOs to swiftly raise capital and expand. In the new era of cryptocurrency, he demonstrated updated entrepreneurial instincts.

After serving 14 years in prison, Yang didn’t vanish. With backing from real estate associates, he launched a flower town project in Yunnan. He set his WeChat profile picture to the iconic windmill of Dutch Village. Standing on construction sites in southwest China, he often gazed northeastward, reminiscing about his Sinuiju experiment.

The times had moved on, but Yang hadn’t abandoned his sharp commercial instincts—he swiftly caught the blockchain and cryptocurrency wave.

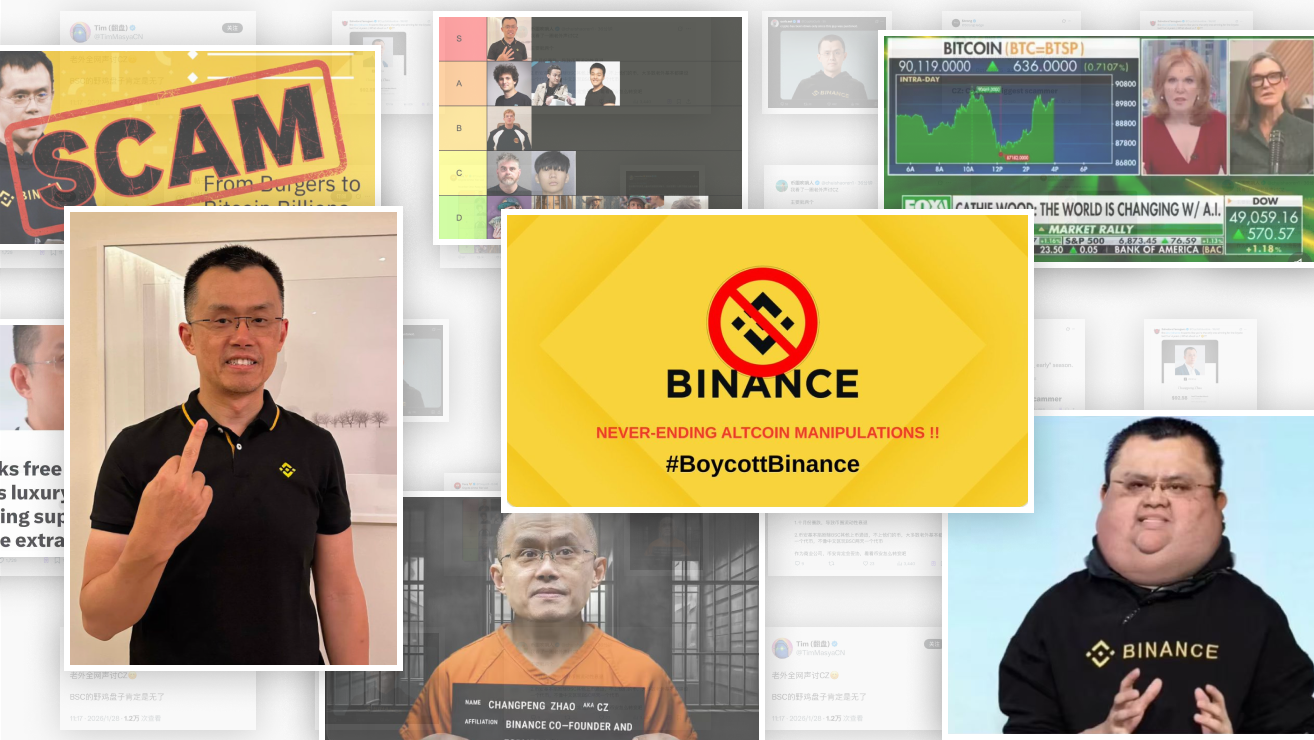

In 2021, Yang orchestrated two blockchain projects: “Marscoin” and “A&A Blockchain Innovation (Mercury Chain).” Riding the blockchain boom, he launched a fresh round of capital-raising campaigns. Ostensibly based on financial innovation, these projects were actually illegal fundraising and pyramid schemes disguised under the “blockchain” label.

Marscoin capitalized on Elon Musk’s fame. Naming the cryptocurrency “Marscoin” attracted investors interested in Musk and blockchain. To boost visibility, Yang hosted high-profile meetups in Shenzhen, Shanghai, and Beijing. For publicity, he invited actor向佐 (Xiang Zuo) to appear, claiming 250,000 online participants, over 600 offline nodes interacting, and 1.73 million live viewers.

Marscoin’s model pretended to mine cryptocurrency using hardware. Users registered to receive virtual “Fire Keys,” then recruited friends to activate more miners for mining rewards. Miners came in three tiers: 300U, 1000U, 3000U, each offering increasing storage multiples and daily interest rates, with annual returns hyped as high as 3x.

Marscoin model

Mars Energy implemented a multi-tier distribution system: first-level referrers earned 5%, second-level 3%, third-level 2%, combining dynamic and static income to lure investors. Withdrawals were never enabled, meaning investors couldn’t access actual profits—they could only sustain the cash flow by recruiting new members.

Marscoin had too many flaws. The grand launch event suffered technical glitches, none of the promised celebrities showed up, and even pre-recorded greeting videos failed to play—appearing amateurish. Poor organization extended to catering complaints: “Red wine costing over ten yuan per bottle, limited to one per table.”

Given Yang’s poor reputation in China, after making money from Marscoin, he fled. Using social visit passes, he arrived in Singapore and shifted his target audience overseas, founding “A&A Blockchain Innovation.”

Same playbook: the first step was creating buzz. But Yang adapted smartly to different audiences. For Marscoin in China, he held a flashy meetup. In Singapore, he targeted charitable organizations and shelters, inviting local pastors and donating 100,000 SGD under the name “A&A Blockchain Innovation.”

Yang Bin donating 100,000 SGD to NHCS (New Hope Community Services)

Rumors suggest Yang used a former Country Garden Forest City sales office as a showroom, displaying mining rigs with GTX 1060 GPUs (4U-8 cards), inviting elderly Singaporeans to attend seminars and invest in ETH mining hardware—when Ethereum traded around $1,600.

Between May 20, 2021, and February 15, 2022, A&A offered local investors a chained mining plan, promising fixed daily returns of 0.5%, allegedly derived from cryptocurrency mining. Marketing materials claimed A&A had signed an agreement with Yunnan Shunai Yunxun Investment Holding Co., Ltd., acquiring 70% ownership of 300,000 mining machines in Yunnan, China.

Yang Bin delivering a speech

These machines supposedly mined Bitcoin and Ethereum to generate profits. In reality, no such agreement existed. A&A operated a cash-flow scheme, using funds from new investors to pay earlier ones.

Under Yang’s direction, CTO Wang Xinghong developed an app allowing investors to seemingly purchase tokens, invest in mining plans, and monitor daily returns. In truth, the app was a centralized “black box” software where administrators manually input fake return figures.

Left: Yang Bin; Right: CTO Wang Bin

Documents show that while operating the mining scheme, Yang also launched a crypto exchange named “AAEX,” claiming to offer various cryptocurrency trading services.

Over time, A&A’s fraud unraveled. In August 2023, Yang and three other A&A executives were charged in Singapore with conspiracy to defraud, involving over $1.8 million. Though 60-year-old Yang refused to admit defeat, his sharp instincts and modernized scams ultimately landed him a six-year prison sentence for eight charges, including conspiracy, participating in fraudulent schemes, and operating without a valid work permit.

“I Am the Adopted Son of Mr. Kim Jong-il”: Yang Bin’s Network of Connections

Poor people obsess over technology. The lower the class, the weaker the interpersonal skills. The higher one climbs, the clearer it becomes: while you think others are focused on tasks, they’re actually focused on relationships. Yang Bin’s ace card was always his network—this very web of connections that powered his rapid ascent.

Looking back, Dutch Village was a project favored from inception. Designated a key provincial project in Liaoning, it received large-scale land allocations, low-interest loans, and other preferential policies. Some whistleblowers even claimed to have seen five teams of prisoners digging underground pipelines under strict supervision at Dutch Village.

During Yang’s trial and judicial investigation, dozens of officials—from the Liaoning Provincial Department of Land and Resources down to the Shenyang Yuhong Land Bureau—were summoned by police to explain their ties to the Dutch Village real estate case. Yang’s sentencing document explicitly stated he illegally profited over 3 million RMB by improperly acquiring arable land and altered government documents to obtain loans—acts involving bribery.

This network enabled Yang to build his business empire and reach the pinnacle of wealth. But as the saying goes, “Rise by the sword, fall by the sword.” Just as Yang proudly planned to list Dutch Village’s tourism project on NASDAQ, political winds in Shenyang shifted. The notorious “Mu Ma corruption scandal” began unfolding—over 100 individuals implicated, including one vice-provincial official, four deputy-mayors, and 17 top party leaders. Shenyang’s leadership underwent a complete overhaul. Simultaneously, the municipal government initiated a sweeping audit of land taxes. Eurasia Dutch Village was ordered to retroactively sign contracts and pay back taxes. Yang refused to pay.

One former associate recalled Yang repeatedly requesting meetings with new city and provincial leaders, only to be politely declined. “Later, though he met them, their attitude was warm yet formal—nothing like previous leaders who supported him unconditionally.” Meanwhile, widespread media skepticism further damaged Yang’s image in capital markets.

But who was Yang Bin? “He always does something unexpected,” said those close to him. As suspicions mounted and political protection vanished amid shifting domestic dynamics, Yang mysteriously disappeared for two months. Some said he fled, others claimed he fell ill, some speculated he was scouting in North Korea or Japan.

Yet two months later, Yang reemerged—miraculously securing a new patron across the Yalu River: the North Korean government. He reinvented himself as “Kim Jong-il’s adopted son” and head of a special economic zone.

Yang’s connection with North Korea likely began in 2001, when Kim Jong-il visited China. During a tour of Shanghai’s Sunqiao Modern Agricultural Development Zone, Kim expressed great interest in glass-greenhouse flowers and vegetables. Yang, hosting the visit, confidently engaged in detailed discussions.

Upon returning to North Korea, Kim summoned Yang, who quickly seized the opportunity. While struggling financially at Dutch Village, Yang began generously showcasing his largesse toward North Korea. Online rumors claim he donated over 100 million yuan; Yang himself said it was “over $20 million in unconditional aid.”

Starting in 2002, Yang constructed a glass greenhouse in front of Mount Paektu, Pyongyang—the burial site of Kim Il-sung. “Let my father see from heaven the progress we’ve made in agriculture,” Kim Jong-il said.

In North Korea, Yang moved freely, acting almost like an ambassador. As ties deepened, Yang embarked on his “political career.” On September 24, 2002, North Korea’s second-in-command, Kim Yong-nam, presented Yang with an appointment letter, naming him Chief Executive of the Sinuiju Special Administrative Region—reportedly ranking equivalent to a North Korean vice premier. “From the moment I assumed office as Chief Executive of Sinuiju, I ceased being a businessman and became a politician,” Yang declared.

Sinuiju, one of North Korea’s largest cities, was a “special administrative region” with independent judiciary and economic systems—akin to Hong Kong—and separated from Dandong, China, only by the Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge. In later interviews, Yang fondly referred to this period, often calling himself “king.” “Hong Kong’s special status lasts 100 years unchanged, but North Korea’s will last forever—what else is that if not kingship?”

Kim Yong-nam presenting appointment letter to Yang Bin

Back at Dutch Village, Yang held a press conference and delivered another speech: “I was an orphan since childhood. The great General Kim Jong-il, with boundless kindness, entrusted me with this responsibility. Under his immense care, I vow to repay him with my life.” He even told the media outright: “I am the adopted son of Mr. Kim Jong-il.”

Reports suggest Yang and Kim Jong-il were indeed close. After Yang’s arrest, North Korea dispatched representatives to Beijing for negotiations. Clearly, Yang excelled at cultivating relationships. Even in the Netherlands, despite fabrications in his past, friends consistently described him as warm, generous, well-connected, and good company—high praise across the board.

Arrogant Yet Insecure: The Tragic Tale of a “Dark Horse Billionaire”

Yet, those closest to him knew that post-success, Yang’s personality became deeply eccentric—undeniably nouveau riche. He frequently flew into rage, erupted hysterically, and quarreled often—even with fellow inmates in prison.

Yang’s arrogance peaked in 2001, when his company Eurasia Agriculture successfully listed in Hong Kong. “For months after the IPO, Yang was full of confidence—each day felt incomplete unless he approved payments in the hundreds of millions,” recalled Dutch Village employees. His travel entourage was equally extravagant: every outing led and followed by fleets of luxury Mercedes-Benz vehicles.

Yang held an extremely high opinion of his wealth and status—bordering on conceit. In 2001, ranked second on Forbes’ list of mainland Chinese entrepreneurs with a net worth of $900 million, Yang dismissed the figure as an underestimate. On the Hurun Rich List, he was labeled “China’s richest man,” and many media outlets echoed this, calling him the true top tycoon—a title he relished.

His arrogance wasn’t limited to flaunting wealth but extended to everyday decisions. Once, touring a building at Dutch Village, he deemed it insufficiently grand and immediately ordered demolition and reconstruction. When reminded it cost over 20 million RMB, Yang scoffed: “Demolish even 20 million!”

Yet, just as Yang basked in success, his pride sowed fatal seeds. In 2002, his business empire began collapsing. But even during legal proceedings, Yang’s arrogance remained unabated.

At trial, he protested indignantly: “I’m the Chief Executive of Sinuiju—how dare you treat me like this?” “You dragged me out of bed without explanation!” Facing conviction on six counts, Yang grew emotional in court, denouncing it as “political persecution,” and defiantly announced appeal: “Appeal? Of course I’ll appeal! Where is justice in this world?” As guards removed him, he ignored warnings and shouted back at reporters: “You’re Hong Kong journalists, right? Dutch Village won’t fall. Heaven will deliver justice.” Chaos ensued.

What shocked reporters most was his display during a meeting with relatives: “Each of you aunts gets one million—go enjoy retirement.” He added on the spot: “Mandela served 27 years and became president. I’ll do 18, come out at 58, and still become president.”

Yang’s arrogance masked deep insecurity. Those who knew him best understood his profound inferiority complex. As a poor orphan, Yang endured hardship throughout childhood. Thus, upon achieving success, he reacted with extreme vanity and clear signs of psychological fracture.

Press conferences and court hearings—Yang’s brightest and darkest moments—featured self-narratives of legendary origins, essential elements of the “dark horse” billionaire myth. Though prone to exaggeration, many details reveal genuine suffering.

At age five, Yang’s father died. His young mother remarried, leaving him orphaned. His grandmother, selling tea, saved coin by coin to raise him. From elementary school, Yang relied on tuition waivers. Back then, his greatest wish was to earn enough money to buy his grandmother nice food.

At eight, Yang found his biological mother and followed her for an hour. When she noticed, she slapped him, threw five yuan on the ground. He picked it up and returned home—only to be slapped again by his grandmother: “Why aren’t you striving? Why don’t you grow up and earn your own money?”

Nanjing has many lakes. Boating is a popular attraction for kids. Yang once rowed—not in a boat, but inside a wooden barrel. Another time, peering through a door crack as a family ate oranges out of curiosity, he was slapped by his grandmother: “Why envy others? Grow up and earn your own!” Such stories were countless.

As a child, nothing hurt Yang more than hearing he was “a kid without parents.” Each time, he felt devastated. Extreme poverty drove him to swear he’d rise above all others.

These experiences shaped Yang’s core identity. His adult arrogance and insecurity, generosity and cunning—all stemmed from childhood poverty, struggle, ambition, and loneliness.

“Did you see last night’s celebration at Wulihe Stadium? We sponsored it.” “Did you see pop star Yang Yuying just walk into my office?” Compared to wealth, the fame and power Yang once held better masked his inner unease—compensating for deep-seated inferiority.

When asked why he poured everything into building a 6,000-acre agricultural estate, he replied: “In Leiden, Netherlands, where I lived, a farming household earns $250,000 annually. In China, calling someone a farmer implies two things: dirtiness and poverty. In the Netherlands, farmers are either bourgeoisie or very wealthy. Why are Chinese farmers so poor? How wonderful it would be if Chinese farmers could be as rich as the Dutch!”

Clearly, being born a poor farmer haunted him—a psychological hurdle he never crossed. It fueled his relentless pursuit of wealth and success, yet trapped him in a dual contradiction of arrogance and insecurity after fame.

Engraved on the pedestal of a statue at Dutch Village Railway Station was his famous quote: “Thirty years on the east bank, thirty years on the west.”

On his desk lay neatly stacked clippings and promotional materials chronicling his “achievements.” Whenever reporters visited, he eagerly pulled them out to share. “For us entrepreneurs, making money isn’t the main goal anymore. The greatest joy is watching what we’ve built rise piece by piece.” In these documents, Yang deliberately portrayed himself as a self-made legend rising from nothing to greatness—an effort reflecting precisely his unresolved inner inferiority and desperate craving for external validation.

To most people, the first impression upon seeing Yang Bin was “so dark.” His skin and face appeared coated in soot. Yet Yang loved wearing white—white shirts, white T-shirts, white pants, even white shoes. This seemed symbolic of his contradictions: a tycoon once worshipped by capital markets, twice reduced to a prisoner.

His mythologized legend was ultimately a tragedy of a gray character. In Yang Bin’s life journey, wealth, status, and honor proved fleeting. As he himself once said: “Thirty years on the east bank, thirty years on the west.” After the glory of the east bank faded, the desolation and decline of the west bank inevitably arrived.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News