Systematically Decoding Fiber: The Grand Experiment of Bridging Lightning Network to CKB

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Systematically Decoding Fiber: The Grand Experiment of Bridging Lightning Network to CKB

This might be the most systematic research report on Fiber.

Written by: Faust & Nickqiao, Geeker Web3

On August 23, the CKB team officially launched Fiber Network—their proposed Lightning Network solution built on CKB. This announcement quickly sparked widespread discussion within the community and caused CKB's price to surge nearly 30% in a single day. The strong reaction stemmed largely from the compelling narrative surrounding Lightning Networks, and the fact that CKB’s Fiber introduces significant upgrades and improvements over traditional Lightning Network designs.

For example, Fiber natively supports multiple asset types—such as CKB, BTC, and stablecoins—and benefits from CKB’s significantly lower transaction fees and faster confirmation times compared to Bitcoin, enabling substantial UX improvements. Fiber also incorporates numerous optimizations in privacy and security.

Moreover, Fiber is interoperable with the Bitcoin Lightning Network, allowing them to form a larger combined P2P network. During past offline events, the CKB team even announced plans to deploy 100,000 physical nodes across both Fiber and the Lightning Network to advance the development of P2P payment systems. Undoubtedly, this presents an extraordinarily ambitious vision.

If the CKB team’s vision is realized in the future, it would be a major boon not only for Lightning Networks but also for CKB and the broader Bitcoin ecosystem. According to mempool data, over $300 million in funds are currently deployed across the Bitcoin Lightning Network, supported by approximately 12,000 nodes forming nearly 50,000 payment channels.

Additionally, spendmybtc.com shows a growing number of merchants adopting Lightning Network payments. As Bitcoin gains wider acceptance, the momentum behind off-chain payment solutions like the Lightning Network and Fiber will only continue to rise.

In the spirit of providing a systematic technical analysis of Fiber, Geeker Web3 has prepared this comprehensive research report on the Fiber framework. While Fiber shares core principles with the Bitcoin Lightning Network as a layer-2 payment channel implementation on CKB, it includes many detailed optimizations.

Fiber’s overall architecture consists of four key components: Payment Channels, WatchTower, Multi-hop Routing, and Cross-Domain Payments. We begin by explaining the most fundamental component: "Payment Channels."

The Foundation of Lightning and Fiber: Payment Channels

Payment channels essentially move transactions off-chain, only submitting the final state to the blockchain for settlement after some time. Since transactions are completed instantly off-chain, they bypass performance limitations inherent to main chains like Bitcoin.

Suppose Alice and Bob jointly open a channel by first creating a multisig account on-chain and depositing funds—say, each deposits 100 units as their respective balances within the off-chain channel. They can then conduct multiple transfers within the channel, and upon exiting, only the final balance is synchronized on-chain, where the multisig account disburses funds accordingly—this is known as “settlement.”

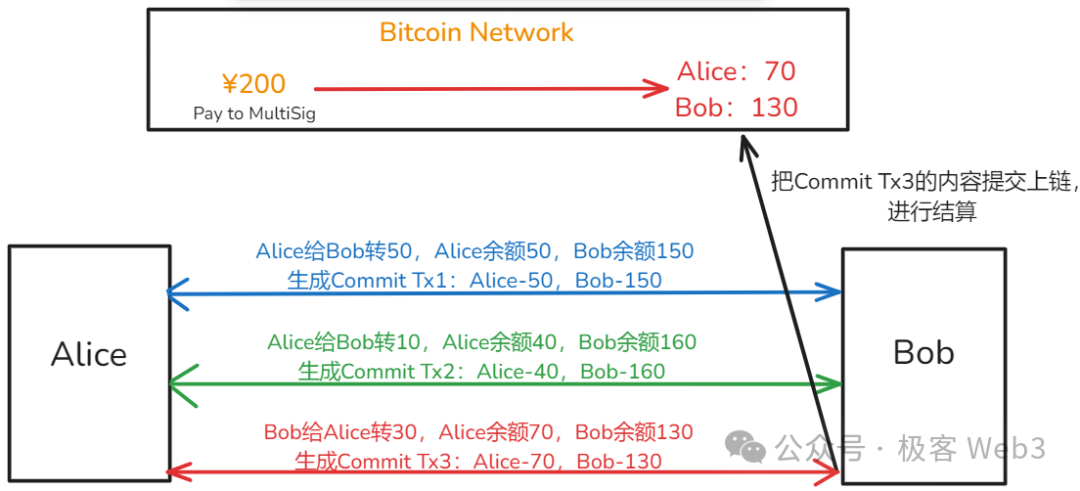

For instance, starting with 100 units each, Alice sends Bob 50, then another 10, followed by Bob sending back 30. Their final balances become Alice: 70, Bob: 130. Notably, the total sum remains constant—a visual analogy using abacus beads shifting back and forth effectively illustrates this concept.

If one party exits the channel, the current balance (Alice: 70 / Bob: 130) is submitted on-chain, and the 200 units in the multisig account are distributed accordingly. While this process appears straightforward, real-world implementation involves handling complex edge cases.

Firstly, you cannot predict when your counterparty might exit the channel. In the above example, Bob could choose to exit after the second transfer or even after the first. There is no enforced timing; participants are free to exit at any moment. To support this flexibility, we must assume either party may submit the latest balance to the chain at any time for settlement.

Hence, the concept of a “commitment transaction” (“Commit Tx”) is introduced. A commitment transaction represents the most recent balance between the two parties in the channel, and a new one is generated with every transfer. When exiting, a participant submits the latest Commit Tx on-chain to withdraw their rightful share from the multisig account.

We can summarize: Commitment transactions enable on-chain settlement of channel balances, and either party can unilaterally submit the latest Commit Tx to exit the channel.

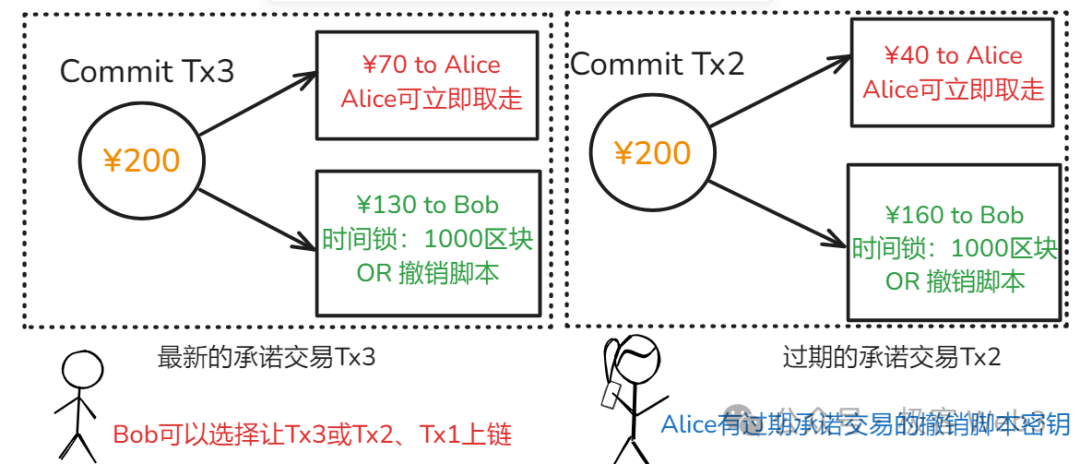

However, there exists a critical malicious scenario: Bob could submit an outdated balance via an expired Commit Tx. For example, after Commit Tx3 is created (where Bob holds 130), Bob might instead submit the earlier Commit Tx2, claiming a balance of 160. Since this reflects an obsolete state, it constitutes classic double-spending.

To prevent such double-spending, effective penalty mechanisms are essential—and the design of these penalties forms the core of any 1-to-1 payment channel. Understanding this mechanism is crucial to truly grasping how payment channels work. In this design, if either party submits an outdated state or Commit Tx on-chain, they won’t profit—they risk losing all their funds to the other party.

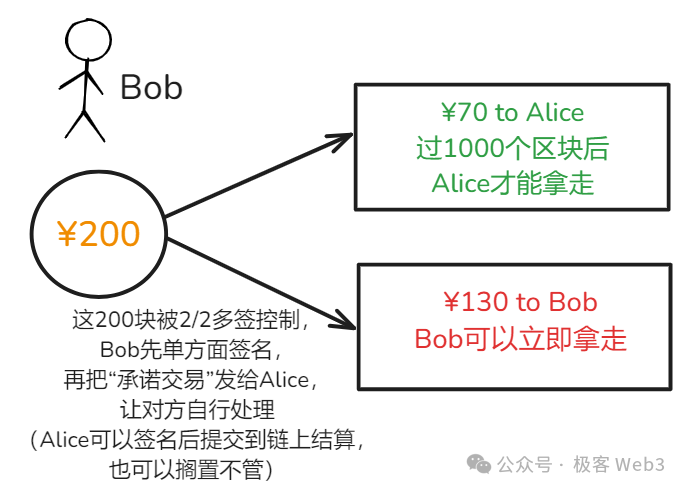

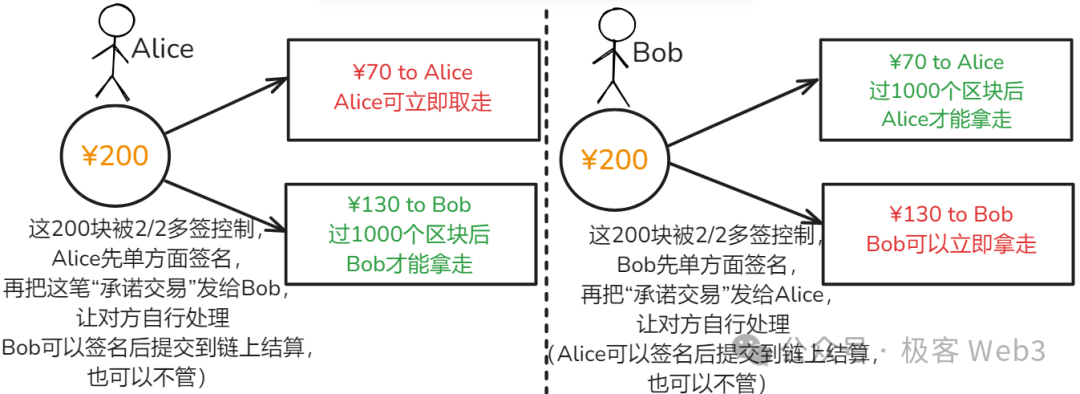

This is achieved through two key concepts: “asymmetric commitment transactions” and “revocation keys”—both of which are critically important. Let’s first explain “asymmetric commitment transactions.” Taking Commit Tx3 from earlier as an example, the diagram below illustrates a commitment transaction:

This commitment transaction is constructed by Bob and sent to Alice for her action. As shown, it's essentially a Bitcoin-style transfer allocating 70 units to Alice and 130 to Bob from the multisig account, but with asymmetric unlocking conditions—one more restrictive for Alice, more favorable for Bob.

After receiving the commitment transaction from Bob, Alice can sign it to satisfy the 2-of-2 multisig requirement, then proactively submit the “commitment transaction” on-chain to exit the channel. If she chooses not to, they may continue transacting within the channel.

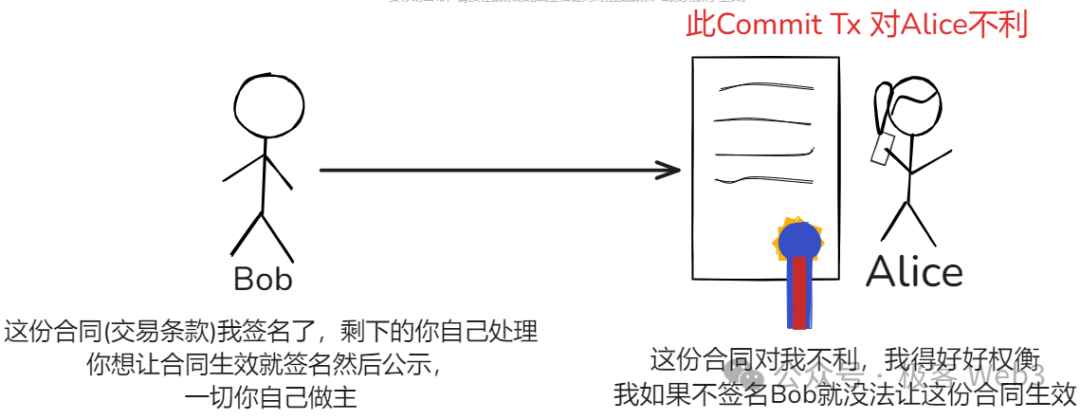

Crucially: this commitment transaction was initiated by Bob and contains terms unfavorable to Alice, who can only accept or reject it—we must preserve some autonomy for Alice. In the payment channel design, only Alice herself can trigger the on-chain execution of a commitment transaction that disadvantages her, because full 2-of-2 multisig signatures are required. Although Bob constructs the transaction locally and signs it, he lacks Alice’s signature.

Meanwhile, Alice can “receive Bob’s signature without returning her own,” much like being presented with a contract unfavorable to you, requiring dual signatures. The other party signs first and hands you the document—you retain control over whether to sign and publish it. You can activate the contract by signing and broadcasting it, or keep it inactive. Clearly, in this case, Alice maintains leverage over Bob.

Now comes the key point: each transfer within the channel generates a pair of mirrored commitment transactions, as illustrated below. Alice and Bob each create versions favorable to themselves, stating their respective balances and entitlements upon exit, then exchange these transaction drafts.

Interestingly, both commitment transactions declare the same withdrawal amount, but differ in spending conditions—this is precisely what gives rise to the concept of “asymmetric commitment transactions” mentioned earlier.

As previously explained, a commitment transaction requires 2-of-2 multisig to become valid. The version Bob creates locally—favorable to himself—is not fully signed, whereas the valid 2-of-2 version remains under Alice’s control. Bob cannot submit it; only Alice can. This creates mutual checks and balances. The reverse logic applies symmetrically.

Thus, Alice and Bob can only voluntarily submit commitment transactions that disadvantage themselves. Once either party submits and confirms a Commit Tx on-chain, the channel closes. Returning to the earlier double-spending scenario—what happens if someone submits an expired Commit Tx?

This is where the “revocation key” comes into play. If Bob submits an expired commitment transaction on-chain, Alice can use the revocation key to claim Bob’s funds.

Refer to the image below: assuming Commit Tx3 is the latest, making Commit Tx2 obsolete, if Bob submits the outdated Tx2, Alice can use its revocation key to withdraw Bob’s funds (provided she acts within the timelock window).

For the latest Tx3, Alice does not possess its revocation key; she only receives it once Tx4 is generated. This behavior stems from cryptographic properties of public-private keys and UTXO mechanics, though a deeper dive into revocation key implementation exceeds this article’s scope.

We can conclude: if Bob dares submit an expired commitment transaction, Alice can seize his funds via the revocation key as punishment. Conversely, if Alice misbehaves, Bob can do the same. Therefore, in a 1-to-1 payment channel, double-spending is effectively deterred—as long as participants act rationally, neither will attempt fraud.

Regarding payment channels, Fiber on CKB offers significant enhancements over the Bitcoin Lightning Network. It natively supports multi-asset transfers—including CKB, BTC, and RGB++ stablecoins—while the Lightning Network only natively supports Bitcoin. Even after Taproot Assets launches, the Bitcoin Lightning Network still won't natively support non-BTC assets, offering only indirect stablecoin support.

Image source: Dapangdun

Furthermore, since Fiber operates atop CKB as its Layer-1, opening and closing channels incur far lower fees than on the Bitcoin Lightning Network, avoiding excessive fee erosion and providing a clear UX advantage.

The 24/7 Security Guard: WatchTower

The revocation key mechanism described earlier has a drawback: channel participants must constantly monitor their counterparties to prevent submission of expired commitment transactions. But no one can stay online 24/7. What happens if your peer cheats while you're offline?

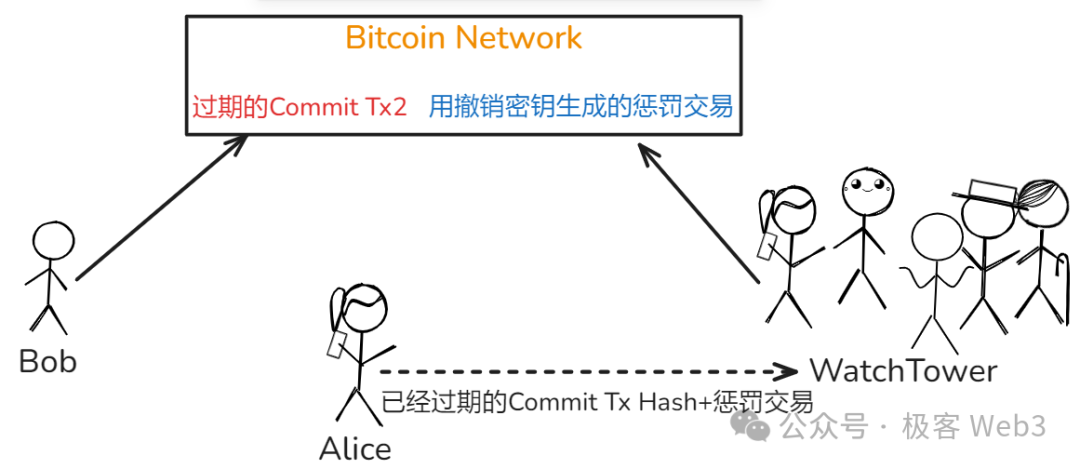

To address this, both Fiber and the Bitcoin Lightning Network implement a WatchTower design to continuously monitor on-chain activity on users’ behalf. If an outdated commitment transaction is detected, the WatchTower intervenes promptly to protect funds and ensure channel security.

Here’s how it works: for each expired commitment transaction, Alice or Bob preconstructs a corresponding penalty transaction (using the revocation key to claim the cheating party’s funds), then sends the plaintext of this penalty transaction to the WatchTower. Once the WatchTower detects an expired commitment transaction on-chain, it immediately broadcasts the penalty transaction to enforce punishment.

To enhance user privacy, Fiber allows users to send only the hash of the expired commitment transaction plus the plaintext of the penalty transaction to the WatchTower. Initially, the WatchTower knows only the hash—not the full details. Only when an expired transaction actually appears on-chain does the WatchTower learn its content and subsequently broadcast the penalty. Thus, unless fraud occurs, the WatchTower never sees users’ transaction history (and even then, only partial information).

It’s worth noting Fiber’s improvement over the Bitcoin Lightning Network. The penalty mechanism based on revocation keys is known as “LN-Penalty,” but Bitcoin’s LN-Penalty has a notable flaw: the WatchTower must store hashes of all expired commitment transactions along with their corresponding revocation keys, creating significant storage overhead.

Back in 2018, the Bitcoin community proposed an alternative called “eltoo” to solve this issue, requiring Bitcoin to activate the SIGHASH_ANYPREVOUT opcode via a fork. The idea is that once an outdated commitment transaction appears on-chain, the latest one can override and penalize it, so users need only retain the most recent state. However, SIGHASH_ANYPREVOUT remains unactivated, preventing eltoo from being implemented.

Fiber implements the Daric protocol, modifying the revocation key design so that a single revocation key applies to multiple expired commitment transactions. This dramatically reduces storage burden on both WatchTowers and user clients.

The Network’s Transportation System: Multi-hop Routing and HTLC/PTLC

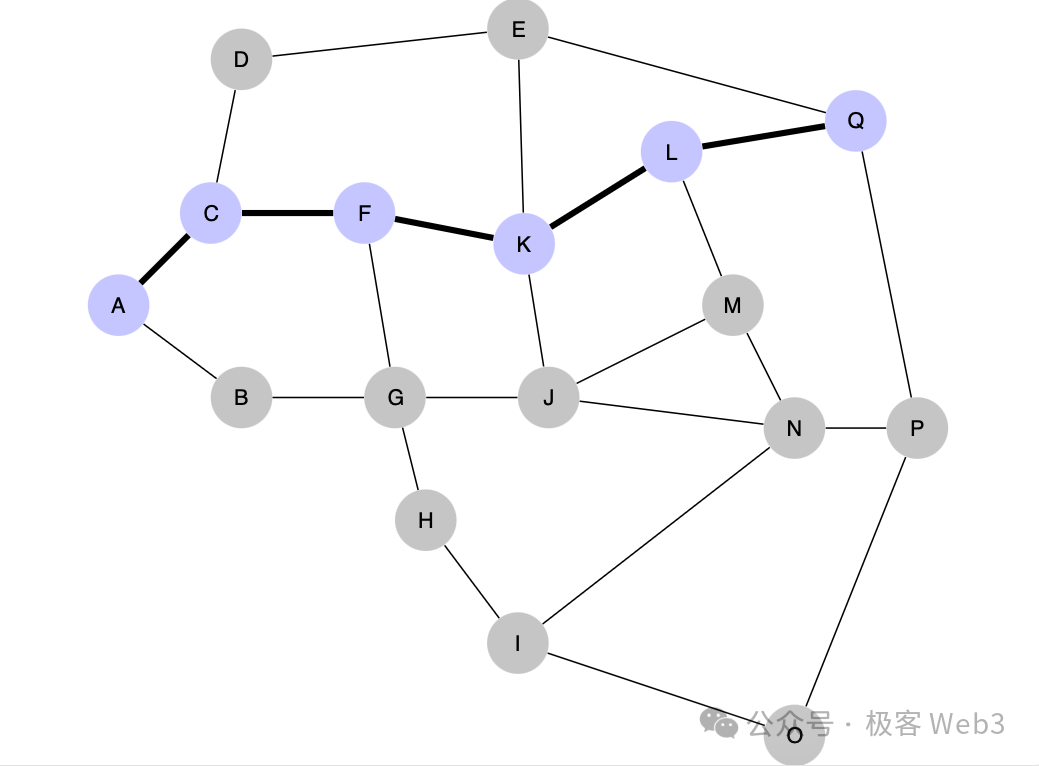

The payment channels discussed so far apply only to direct 1-to-1 interactions. A key feature of Lightning Networks is multi-hop payments—routing through intermediate nodes to enable transfers between parties without direct channels. For example, if Alice and Ken lack a direct channel, but Ken has one with Bob, and Bob has one with Alice, Bob can act as an intermediary, enabling Alice to pay Ken. “Multi-hop routing” refers to constructing such payment paths through intermediaries.

Multi-hop routing enhances network flexibility and reach. However, senders must know the status of public nodes and channels. In Fiber, all public channels and network topology are fully transparent, allowing any node to access others’ network data. Given the dynamic nature of network states, Fiber employs Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm to find optimal routes with minimal hops, efficiently establishing transfer paths.

However, trustworthiness of intermediate nodes must be addressed: How can you ensure they’re honest? For instance, if Bob acts as an intermediary between Alice and Ken, he could potentially withhold Alice’s payment of 100 units. Mechanisms must exist to deter such misconduct. HTLC and PTLC are designed precisely to solve this problem.

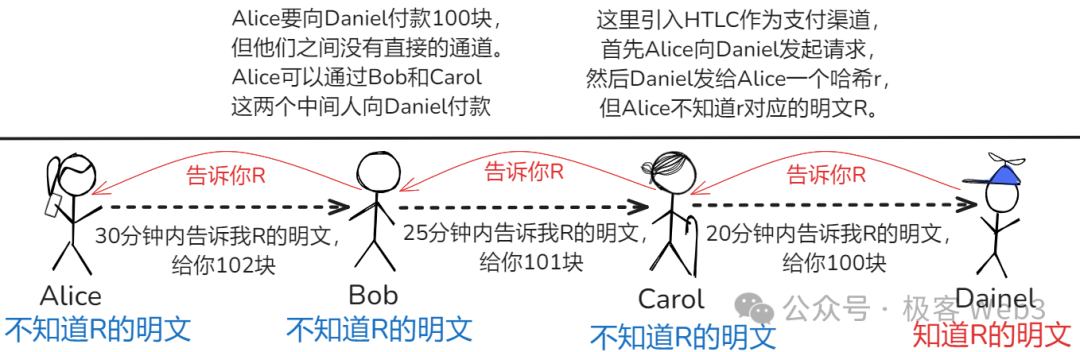

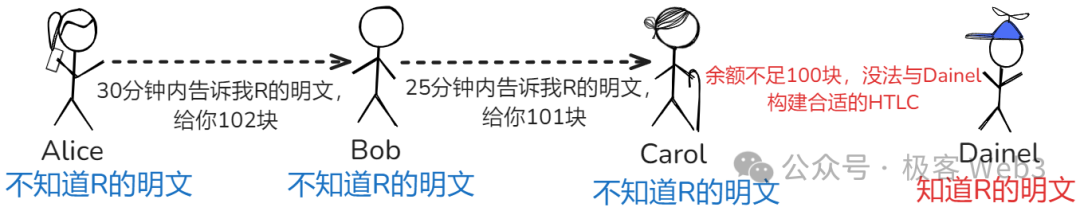

Suppose Alice wants to pay Daniel 100 units, but they lack a direct channel. She discovers a route via intermediaries Bob and Carol. An HTLC-based payment channel is established. First, Alice initiates a request to Daniel, who responds with a hash value r—but Alice does not know the preimage R of r.

Alice then creates an HTLC in her channel with Bob: she offers 102 units, but Bob must reveal the preimage R within 30 minutes, otherwise Alice reclaims the funds. Similarly, Bob sets up an HTLC with Carol: he offers 101 units, contingent on Carol revealing R within 25 minutes. Carol repeats the process with Daniel: offering 100 units, redeemable only if Daniel reveals R within 20 minutes.

Daniel realizes that the R Carol demands is the same one Alice seeks—after all, only Alice should care about R’s value. So Daniel cooperates, reveals R to Carol, and receives his 100 units—achieving Alice’s goal.

Next, Carol reveals R to Bob and collects 101 units; Bob reveals R to Alice and receives 102 units. Analyzing net outcomes: Alice loses 102 units, Bob and Carol each gain 1 unit, and Daniel receives 100 units. The 1-unit profits for Bob and Carol represent fees collected from Alice.

Even if an intermediary stalls—e.g., Carol fails to pass R to Bob—Bob incurs no loss: after timeout, he can reclaim his HTLC funds. The same applies to Alice.

However, Lightning Networks face reliability issues with long routes: excessive hops reduce success rates. Intermediaries may go offline, or lack sufficient balance to establish specific HTLCs (e.g., each must hold at least ~100+ units). Each additional hop increases failure risk.

Additionally, HTLCs may compromise privacy. Although onion routing provides some protection—encrypting routing info per hop so only adjacent peers are known, hiding the full path—HTLCs can still leak relational clues through common secrets. From a god’s-eye view of the following path:

Assume Bob and Daniel are controlled by the same entity, regularly receiving HTLCs. They notice that whenever Alice and Carol initiate HTLCs, the requested secret is always the same, and Eve (Daniel’s downstream peer) consistently learns R. Therefore, Daniel and Bob infer that Alice and Eve are linked via a payment path, since they repeatedly correlate around the same secret, enabling surveillance of Alice and Eve’s relationship.

To address this, Fiber adopts PTLCs—improving privacy over HTLCs by using distinct keys for each hop. Observing PTLC unlock keys alone cannot reveal transaction linkages. Combined with onion routing, Fiber becomes an ideal choice for private payments.

Furthermore, traditional Lightning Networks are vulnerable to “replacement cycling attacks,” which can lead to theft of assets held by intermediate nodes. This flaw was serious enough to prompt developer Antoine Riard to exit Lightning Network development. To date, Bitcoin’s Lightning Network lacks a fundamental fix, making this an ongoing pain point.

Currently, the CKB team mitigates this attack via transaction pool-level modifications, enabling Fiber to resist replacement cycling. Given the complexity of this attack and its resolution, we omit further detail here. Interested readers may refer to BTCStudy’s related articles or official CKB documentation.

Overall, Fiber delivers substantial improvements over traditional Lightning Networks in both privacy and security.

Cross-Domain Atomic Payments Between Fiber and Bitcoin Lightning Network

Using HTLCs and PTLCs, Fiber enables cross-domain payments with the Bitcoin Lightning Network while ensuring atomicity—either all steps succeed, or all fail, eliminating partial completion risks.

With atomicity guaranteed, cross-network transactions avoid financial loss, allowing Fiber and the Bitcoin Lightning Network to interoperate seamlessly. For example, payment paths can span both networks, enabling direct transfers from Fiber to users on the Bitcoin Lightning Network (receiving end limited to BTC), or exchanging CKB and RGB++ assets on Fiber for equivalent BTC within the Lightning Network.

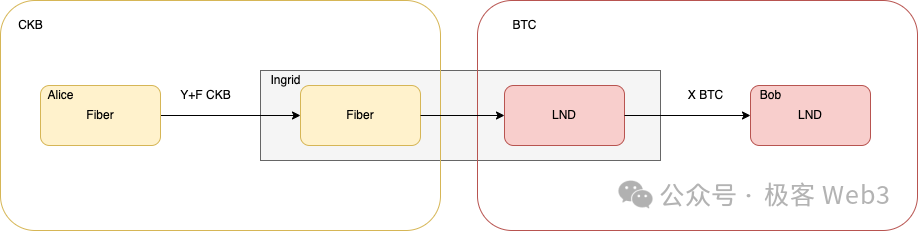

Here’s a simplified explanation: suppose Alice runs a node on Fiber, and Bob operates one on the Bitcoin Lightning Network. Alice wishes to send funds to Bob and uses a cross-domain relay service—in this case, Ingrid—to complete the transfer. Ingrid runs nodes on both Fiber and the Bitcoin Lightning Network, acting as an intermediary.

If Bob wants to receive 1 BTC, Alice negotiates an exchange rate with Ingrid—say, 1 CKB for 1 BTC. Alice sends 1.1 CKB to Ingrid via Fiber, and Ingrid sends 1 BTC to Bob via the Bitcoin Lightning Network, keeping 0.1 CKB as a fee.

The actual mechanism involves establishing payment routes between Alice/Bob and Ingrid—i.e., Alice → Ingrid → Bob—using HTLCs. As previously explained, Bob must reveal the preimage R to receive funds. Once Ingrid obtains R, it can unlock the HTLC funds from Alice.

Importantly, the two cross-domain actions—one on Bitcoin Lightning, one on Fiber—are atomic: either both HTLCs are unlocked (successful payment), or neither (payment fails). There is no scenario where Alice pays but Bob doesn’t receive.

(In theory, Ingrid could learn R and refuse to unlock Alice’s HTLC—but this harms Ingrid, not Alice. Hence, Fiber’s design protects end users.)

This method enables trustless fund transfers between different P2P networks with minimal modification.

Additional Advantages of Fiber Over Bitcoin Lightning Network

As noted earlier, Fiber supports native CKB assets and RGB++ assets—especially stablecoins—giving it immense potential in instant payment scenarios and making it better suited for everyday microtransactions.

Moreover, the Bitcoin Lightning Network suffers from a major pain point: liquidity management. Recall that total channel balance is fixed. If one party exhausts their balance, they cannot send further payments unless the other party sends funds first—requiring rebalancing or opening new channels.

In complex multi-hop networks, intermediate nodes with insufficient balance may block outward payments, causing entire routes to fail. This remains a key limitation. Current solutions focus on efficient liquidity injection to keep nodes well-capitalized.

However, on the Bitcoin Lightning Network, liquidity injection, channel opening, and closure all occur on the Bitcoin chain. High BTC fees severely degrade UX. For example, opening a $100-capacity channel costing $10 in fees means losing 10% upfront—an unacceptable cost for most users. The same applies to liquidity replenishment.

Fiber offers a decisive advantage here. First, CKB’s TPS vastly exceeds Bitcoin’s, with fees at the cent level. Second, to tackle liquidity shortages, Fiber plans to collaborate with Mercury Layer on a novel solution that moves liquidity injection off-chain, resolving both UX and cost barriers.

To conclude, we’ve systematically reviewed Fiber’s technical architecture. The comparative summary between Fiber and the Bitcoin Lightning Network is illustrated above. Given the vast and intricate knowledge domain involved, a single article cannot cover every aspect. In the future, we will publish a series of articles exploring Lightning Networks and Fiber in greater depth—stay tuned.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News