What are we talking about when we talk about economic models?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

What are we talking about when we talk about economic models?

Economic model is the most important design for blockchains targeting long-term operation, without exception.

Author: Xiao Zhu Web3

Starting from Bitcoin's Shutdown Price

Recently, as Mt. Gox began repaying Bitcoin and the German government frequently sold its Bitcoin holdings, Bitcoin’s price briefly dropped below $54,000 (it has since rebounded above $60,000), touching the "shutdown price" for some Bitcoin mining machines.

According to research data, if Bitcoin falls to $54,000, only ASIC miners with efficiency exceeding 23W/T can remain profitable—only five models of mining equipment could barely survive under such conditions. This means that if Bitcoin's price drops below shutdown levels, smaller-scale miners with lower risk tolerance may exit to cut losses. When these miners leave, they often sell their Bitcoin for cash and discount their mining hardware, triggering further downward pressure on Bitcoin prices—a phenomenon known as miner capitulation.

The so-called shutdown price is essentially the cost threshold at which Bitcoin mining becomes unprofitable. How exactly is this cost calculated? To answer this question, we must first understand Bitcoin's economic model and Proof-of-Work (PoW) mechanism.

Bitcoin has a pre-programmed total supply of 21 million coins. A block is mined approximately every 10 minutes, rewarding miners with a certain number of Bitcoins. Initially, the reward was 50 BTC per block, halving roughly every four years (every 210,000 blocks). The most recent halving occurred on April 23, 2024, at block height 840,000, reducing the block reward to 3.125 BTC. In addition to block rewards, miners also collect transaction fees, typically ranging between 0.0001 and 0.0005 BTC per transaction. Fees are market-driven: the more users transact on the network, the busier miners become, and transactions with insufficient fees risk being ignored.

When transactions occur on the Bitcoin network, they are placed in a memory pool (mempool). Miners then select a group of transactions from the mempool and attempt to form a new block. To do this, miners must find a specific nonce value that, when combined with the block data, produces a hash meeting the network's difficulty target. This process is called “mining.” Whoever computes a valid hash first earns the right to record the block—i.e., successfully mines it. The difficulty target adjusts dynamically every 2,016 blocks (approximately every two weeks) to maintain an average block time of around 10 minutes. Therefore, the higher the total network hashrate, the greater the difficulty.

The computing power mentioned above refers to a mining machine’s ability to perform hash calculations per second. Currently, hashrate is commonly measured in TH/s (terahashes per second), meaning 10^12 hashes per second. The current global hashrate is about 630 EH/s, or 6.3×10^20 hashes per second. Thus, each terahash theoretically mines about 8×10^(-7) BTC per day. For miners, aside from initial hardware purchase and operational management costs, electricity is the primary ongoing expense. Take the Antminer S19 Pro as an example: rated hashrate of 110 T, power consumption of 3,250 W. This translates to approximately 0.709 kW of daily power usage per T. Electricity prices vary significantly by region; assuming $0.055/kWh, the break-even cost to mine one Bitcoin is around $50,000. The chart below from F2Pool's Bitcoin mining data aligns closely with this estimate.

All the above assumes a total network hashrate of 630 EH/s. Once “miner capitulation” occurs, the total hashrate will drop, lowering the cost to mine one Bitcoin. Conversely, if Bitcoin’s price rises and mining becomes more profitable, more miners join, increasing the total hashrate and thus raising the mining cost.

Therefore, Bitcoin’s “shutdown price” is ultimately the result of market dynamics and miner behavior—all built upon Bitcoin’s simple yet effective economic model.

Economic Model Under PoS

In PoW blockchains like Bitcoin, miners are the most critical participants. However, in PoS blockchains (such as Ethereum and Solana), there are no miners. What does their economic model look like?

First, we need to understand that the biggest difference between PoS and PoW lies in consensus participation: PoS introduces准入 mechanisms where nodes must stake a certain amount of native tokens to qualify for block validation. These staking participants are known as validators.

Second, for platforms with inflationary token supplies (like Ethereum and Solana), inflation must be carefully managed. New tokens are typically issued as validator rewards, while token burn mechanisms (e.g., transaction fee burning or treasury buybacks) help offset issuance. A balance between inflation and deflation is crucial—temporary imbalances are acceptable, but long-term sustained inflation or deflation must be avoided to ensure economic stability.

Lastly, platform token utility differs significantly from Bitcoin. While Bitcoin is primarily used for transaction fees, PoS tokens generate yield through staking rewards. Many networks support delegated staking, allowing users to participate without running their own validator node. This reduces circulating supply and enhances economic stability. Liquid staking—the common term for third-party protocols offering staking derivatives—is based on such delegation designs, with APR derived from staking rewards (and MEV).

Ethereum

Ethereum launched with an initial supply of 72 million ETH: 60 million were distributed during a 2014 crowdfunding campaign (averaging ~$0.30 per ETH), while the remaining 12 million were split—half to early contributors and half reserved for the Ethereum Foundation—at network launch in 2015. Today, Ethereum’s total supply is approximately 120 million.

In September 2022, Ethereum transitioned from PoW to PoS (The Merge), activating the Beacon Chain. This marked a turning point in Ethereum’s monetary policy. Before the merge, Ethereum inflated by about 4.84 million ETH annually (~4% inflation rate). After the merge, annual issuance dropped to ~3.01 million ETH (~2.5% inflation). However, due to EIP-1559, which burns part of every transaction fee, Ethereum has been net deflationary for much of the time since the upgrade, with an average deflation rate of ~1.4%.

To become a validator on the Beacon Chain, a node must stake 32 ETH. Staking more than 32 ETH does not increase a validator’s weight in the network. Each epoch consists of 32 slots (~12 seconds each), with one block produced per slot. Rewards are distributed per epoch and derived from a base reward—the theoretical maximum reward per validator under ideal conditions. Block proposers receive 1/8 of the base reward, while the rest goes to attesters (who vote consistently with the majority) and sync committee members. Actual rewards depend on a validator’s effective balance and the total number of active validators. Readers interested in details should explore Ethereum’s Gasper consensus, one of the protocol’s most complex components.

Given the 32 ETH minimum requirement, lack of native delegation, and a 27-hour withdrawal delay, solo staking poses significant barriers. As a result, liquid staking protocols have emerged to make participation easier. These protocols pool user funds to bypass the 32 ETH threshold, manage validator operations automatically, and issue liquid staking tokens (LSTs) that users can trade or use across DeFi applications, improving capital efficiency.

Lido, the market leader in Ethereum’s liquid staking space, issues stETH and dominates the LST landscape. Through Lido, ordinary users can stake any amount of ETH, receiving stETH in return—which can later be swapped back to ETH, solving key limitations of native staking. Currently, 32.54 million ETH are staked on Ethereum (~27% of total supply), with Lido contributing 9.8 million (~30% of all staked ETH).

Solana

Solana launched with an initial supply of 500 million SOL: 38% allocated to community reserve funds, 12.5% to team members, 12.5% to the Solana Foundation, and 37% to investors. Current total supply is about 580 million SOL, with 460 million circulating (~80% circulation rate). The remaining 20% is locked for investors and team members, with a major unlock scheduled for March 2025—approximately 45 million SOL.

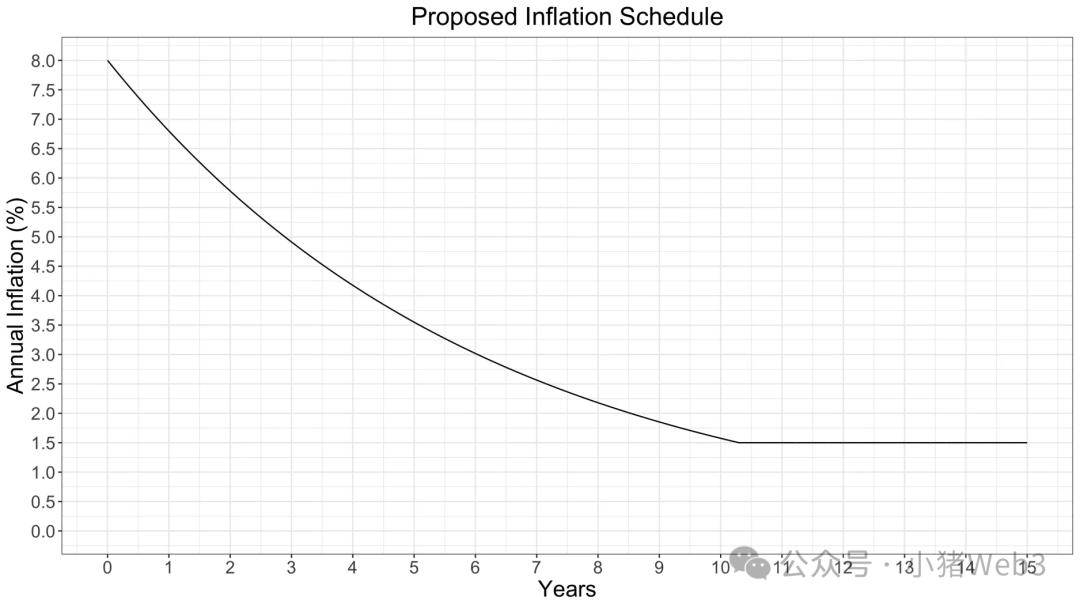

Solana’s initial inflation rate was 8%, decreasing annually by 15%, converging toward a long-term inflation rate of 1.5%.

Solana imposes no minimum staking requirement for validators. Instead, voting power and rewards are proportional to the amount staked. The network supports delegated staking: users can delegate their SOL to existing validators to earn yield. Importantly, delegation does not transfer ownership—SOL remains in the user’s wallet, maintaining full security. There are currently around 1,500 validator nodes, with average APR around 7%.

Validators earn credits by submitting correct and successful votes (which themselves are transactions requiring fee payments). Proposers receive no extra credits; block rewards consist solely of transaction fees, with only 50% going to the validator and the other 50% burned. At the end of each epoch, accumulated credits are converted into SOL rewards via a stake-weighted calculation—each validator receives a share of rewards proportional to their percentage of total network credits.

The state of liquid staking on Solana differs sharply from Ethereum. Over 80% of circulating SOL is staked—far exceeding Ethereum’s 27%. Yet, LSTs represent only 6% of staked supply (compared to over 40% on Ethereum). The reason is clear: Solana natively supports delegation, and its DeFi ecosystem is still nascent. Problems that Lido and similar projects solve on Ethereum simply don’t exist on Solana. Jito leads Solana’s LST market by delegating user SOL to MEV-enabled validators (using the Jito-Solana client), capturing MEV profits and distributing them as additional yield. As a result, Jito offers higher APR—currently up to 7.92%—and JitoSOL accounts for 3% of all staked SOL.

Conclusion

The economic model is the single most important design consideration for any blockchain intended for long-term operation. Compared to the simple and effective model of PoW chains like Bitcoin, PoS blockchains such as Ethereum and Solana feature far more complex designs—requiring careful calibration of staking mechanics, incentive structures, inflation parameters, and token utilities.

Looking at newer blockchains, the vast majority adopt PoS rather than PoW. Beyond being more energy-efficient, PoS offers better throughput and faster transaction finality, enabling higher transaction processing capacity—critical foundations for mass adoption.

At comparable cost, PoS also provides stronger security and faster recovery from attacks. Validators are economically aligned stakeholders: honest ones are rewarded, malicious ones are penalized. However, this also leads to wealth concentration, as those with the largest stakes earn the highest returns.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News