DeFi Economic Models Explained: Four Incentive Models from a Value Flow Perspective

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

DeFi Economic Models Explained: Four Incentive Models from a Value Flow Perspective

Value Flow is not the entirety of tokenomics, but rather the product's intrinsic value flow designed under tokenomics.

Author: DODO Research

"[Money] it drives the world, for better or worse. Economic incentives drive entire swathes of human populations to behave" — Chamath Palihapitiya

I. Incentive Compatibility in Tokenomics

Decentralized cryptographic P2P systems were not new when Bitcoin debuted in 2009.

You may have heard of the BitTorrent protocol, commonly known as BT download—a peer-to-peer file-sharing protocol primarily used to distribute large volumes of data across Internet users. It utilized a form of economic incentive; for example, "seeders" (users who upload complete files) receive faster download speeds. However, this early decentralized system, launched in 2001, still lacked a well-designed economic incentive mechanism.

The lack of economic incentives stifled these early P2P systems, making it difficult for them to thrive over time.

(Coincidentally, in 2019, the developers of the BitTorrent protocol launched the BitTorrent Token (BTT), later acquired by TRON. They chose to use cryptocurrency to provide economic incentives to improve the performance and user interaction of the BitTorrent protocol. For instance, users can spend BTT to boost their download speed or earn BTT by sharing files.)

In 2009, when Satoshi Nakamoto created Bitcoin, he introduced economic incentives into the P2P system.

From DigiCash to Bit Gold, various attempts to create decentralized digital cash systems had never fully solved the Byzantine Generals Problem. But Satoshi implemented a Proof-of-Work (PoW) consensus mechanism combined with economic incentives, solving this seemingly intractable issue—how nodes could reach consensus. Bitcoin not only provided an alternative store of value for those seeking to replace existing financial systems but also combined cryptocurrency with incentives to offer a novel, general-purpose design and development methodology, ultimately forming today’s powerful and vibrant P2P payment network.

From Satoshi's "Galilean era," crypto-economics has evolved into Vitalik's "Einstein era."

More expressive scripting languages enabled complex transaction types and gave birth to a more general-purpose decentralized computing platform. After Ethereum switched to Proof-of-Stake (PoS), token holders became network validators and earned additional tokens through staking. Beyond controversy, compared to Bitcoin’s current ASIC mining approach, this is indeed a "more inclusive token distribution method."

Designing a tokenomic model is essentially designing an "incentive-compatible" game-theoretic mechanism. – Hank, BuilderDAO

Incentive compatibility is an important concept in game theory, first proposed by economist Roger Myerson in his seminal work "Game Theory: Analysis of Conflict." Published in 1991, this book became a key reference in the field of game theory. In it, Myerson elaborated on the concept of incentive compatibility and its significance.

Academically, it can be understood as a mechanism or rule design where participants act according to their true interests and preferences without needing to deceive, cheat, or act dishonestly to achieve better outcomes. This kind of game structure enables individuals pursuing personal gain maximization to simultaneously achieve collective benefit maximization. For example, in Bitcoin’s design, when expected revenue exceeds cost, miners continue investing computational power to maintain the network, enabling users to conduct secure transactions on the Bitcoin ledger—the trust machine that now holds over $40 billion in value and processes over $600 million in transaction volume daily.

Within tokenomics, using tokens and rules to guide multi-party participant behavior and achieve better incentive compatibility expands the scale and upper limits of possible decentralized structures or economic benefits—an eternal challenge.

Tokenomics plays a decisive role in the success or failure of cryptocurrency projects. And how to design incentives to achieve incentive compatibility, in turn, plays a decisive role in the success or failure of tokenomics.

This is analogous to monetary and fiscal policy for national governments.

When protocols become nations, they must set monetary policies such as token issuance rates (inflation rates) and decide under what conditions new tokens are minted. They need to regulate fiscal policy—adjusting taxation and government spending—typically represented by transaction fees and treasury funds.

It’s complex. As proven by thousands of years of human economic experimentation and governance building, designing models to coordinate human nature and economics is incredibly difficult. There have been errors, wars, even regressions. Crypto, with less than two decades of history, must also iterate through repeated trial and error (e.g., the Terra incident) to create better models for a long-term successful and resilient ecosystem. This is clearly the kind of mindset reset the market needs during prolonged crypto winters.

II. Classification, Goals, and Design of Different Economic Models

When designing economic models, we must clarify the target of token design. Public blockchains, DeFi (decentralized finance), GameFi (gaming + finance), and NFTs (non-fungible tokens) represent different categories within the blockchain space, each differing slightly in economic model design.

Public chain token design resembles macroeconomics, while others lean toward microeconomics; the former focuses on overall supply-demand equilibrium within the system and ecosystem, while the latter emphasizes product-level supply-demand dynamics between users and markets.

Different project categories also have entirely different design objectives and core considerations. Specifically:

-

Public Chain Economic Model: Different consensus mechanisms determine different economic models for public chains. However, they share a common goal: ensuring stability, security, and sustainability of the blockchain. Therefore, the core lies in using token incentives to attract and retain sufficient validator nodes to maintain the network. This typically involves cryptocurrency issuance, incentive mechanisms, node rewards, and governance to sustain economic stability.

-

DeFi Economic Model: Tokenomics originated with public chains but matured in DeFi projects, which will be analyzed in detail later. DeFi economic models usually involve lending, liquidity provision, trading, and asset management. The design objective is to encourage users to provide liquidity, participate in lending and trading, and receive interest, rewards, and yields. In DeFi models, the design of the incentive layer is central, such as how to encourage token holders to hold rather than sell, and how to balance interests between LPs and governance token holders.

-

GameFi Economic Model: GameFi combines gaming and financial elements, aiming to provide gamers with financial rewards and economic incentives. GameFi economic models typically include issuance, trading, and revenue distribution of in-game virtual assets. Compared to DeFi, GameFi model design is more complex; since revenue from transaction fees is central, increasing user reinvestment demand becomes the primary design imperative, though this inherently challenges game playability. This causes most projects to inevitably exhibit Ponzi-like structures and spiral effects.

-

NFT Economic Model: NFT project economic models typically involve NFT issuance, trading, and holder rights. The design goal is **to provide NFT holders opportunities to create, trade, and earn value, encouraging greater participation from creators and collectors**. This further divides into NFT platform economic models and project-specific models. The former competes on royalty fees, while the latter focuses on solving economic scalability—such as increasing repeat sales and cross-domain fundraising (see Yuga Labs).

Despite their unique designs, these models may overlap or intersect. For example, DeFi projects can integrate NFTs as collateral, and GameFi projects can use DeFi mechanisms for fund management. In the evolution of economic model design, whether at the business or incentive layer, DeFi has developed richer frameworks, and many DeFi models are widely adopted in GameFi, SocialFi, and other projects. Thus, DeFi economic model design is undoubtedly a critical area for deep study.

III. DeFi Economic Models Through the Lens of Incentive Mechanisms

If categorized by business logic, DeFi economic models can be broadly divided into three main types: DEX, Lending, Derivatives. If classified by characteristics of the incentive layer, they fall into four patterns: governance model, staking/cashflow model, vote-escrow ("ve" and "ve(3,3)" models), and es-mining model.

Among these, the governance and staking/cashflow models are relatively simple, exemplified by Uniswap and SushiSwap respectively. A brief summary follows:

-

Governance Model: Tokens grant only governance rights over the protocol; e.g., UNI represents governance rights over Uniswap. The Uniswap DAO is the decision-making body where UNI holders propose and vote on decisions affecting the protocol, including managing the community treasury and adjusting fee rates.

-

Staking/Cashflow Model: Tokens generate ongoing cashflows; e.g., Sushiswap attracted liquidity early by distributing its SUSHI token to early LPs, executing a "vampire attack" on Uniswap. Beyond trading fees, SUSHI token holders also receive a share of 0.05% of protocol revenue.

Each has strengths and shortcomings. UNI’s governance utility has long been criticized for lacking value realization and failing to reward early-risk-taking LPs and users; meanwhile, Sushi’s excessive emissions caused price drops, leading some liquidity to return to Uniswap.

In the early days of DeFi, these two were common economic models. Later models iterated upon them. Next, we analyze vote-escrow and es-mining models using Value Flow analysis.

This article primarily uses the Value Flow method to study projects, abstracting internal value flows—including real protocol revenues, redistribution pathways, incentive layers, and token movements. Together, these constitute the core business model, continuously adjustable and optimized via Value Flow. While Value Flow doesn’t capture all aspects of tokenomics, it reflects product-level value movement based on tokenomic design. Combined with initial token allocations and unlock schedules, it offers a comprehensive view of a protocol’s tokenomics. During this process, supply-demand dynamics are adjusted to enable value capture.

IV. Vote Escrow

Vote escrow emerged from the early困境 of “mine-and-dump” DeFi projects. The solution focused on boosting user holding incentives and aligning stakeholder interests for long-term protocol growth. After Curve pioneered the ve model, subsequent protocols iterated on it, mainly through ve and ve(3,3) models.

ve Model: The core mechanism allows users to lock tokens to receive veTokens. veTokens are non-transferable, non-circulating governance tokens. The longer the lock-up period (subject to a maximum), the more veTokens received. Users gain voting power proportional to their veToken weight, influencing decisions like which liquidity pools receive emission rewards—directly impacting personal returns and strengthening holding incentives.

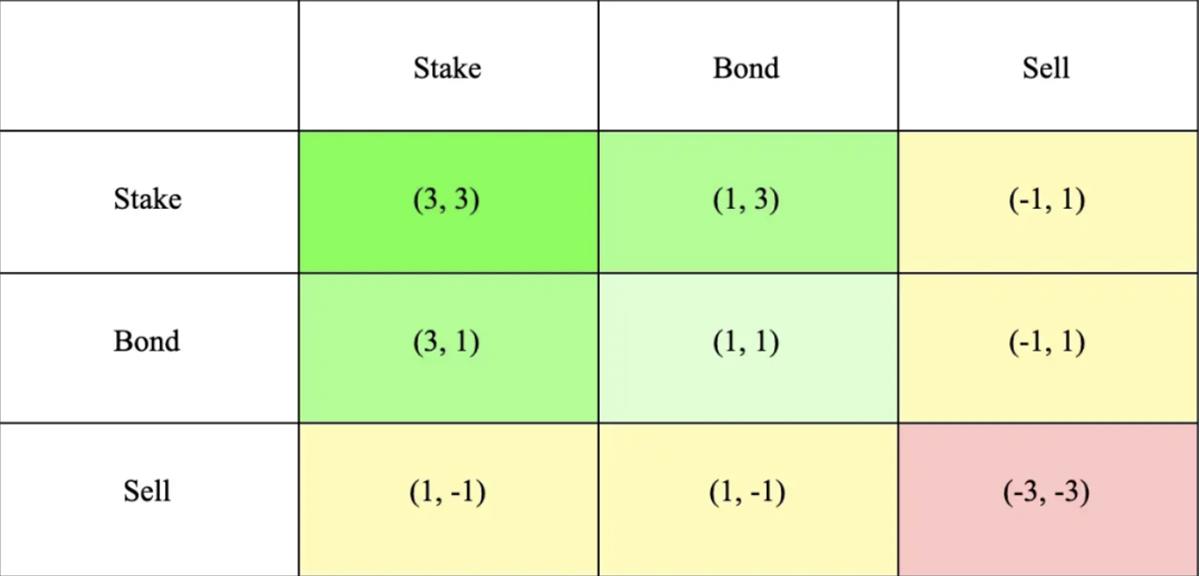

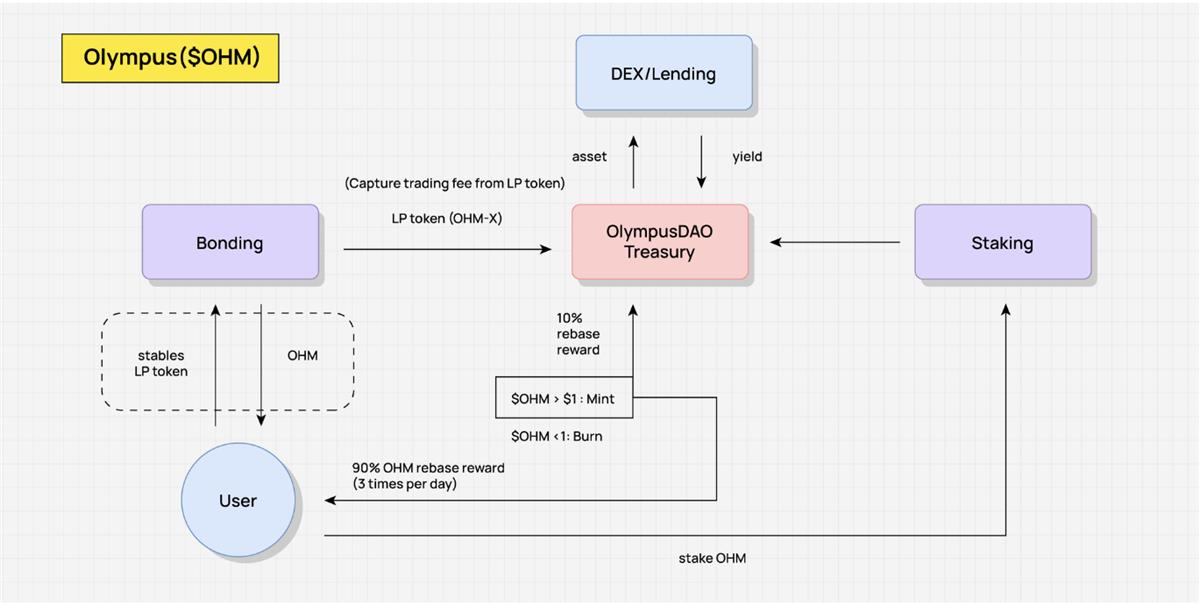

ve(3,3) Model: The ve(3,3) model combines Curve’s ve model with OlympusDAO’s (3,3) game theory. (3,3) refers to payoff outcomes under different investor behaviors. In a simplified Olympus model with two investors choosing among staking, bonding, or selling, mutual staking yields the highest joint payoff—(3,3)—encouraging cooperation and staking.

Curve — Pioneer of the ve Model

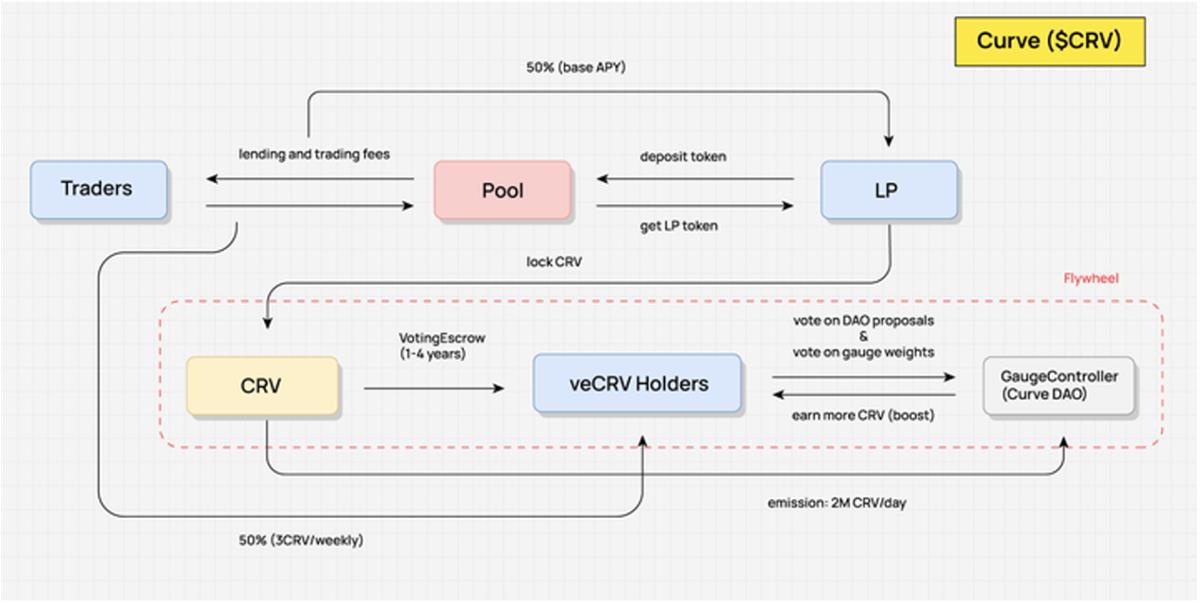

In the following Value Flow diagram of Curve, we see that CRV holders cannot capture any protocol-related value unless they lock CRV to obtain veCRV. Value capture occurs through:trading fees, boosted market-making rewards, and governance voting rights.

-

Trading Fees: Users who lock CRV receive 50% of platform-wide trading fees (0.04% per pool) distributed in 3CRV tokens. The other 50% goes to liquidity providers.

-

Boosted Market-Making Rewards: Curve LPs who lock CRV can use the Boost feature to increase their CRV rewards from market-making, thereby raising their overall APR. The required CRV depends on the pool and the LP’s capital size.

-

Governance Voting Rights: Curve governance requires veCRV, covering parameter changes, adding new liquidity pools, and allocating CRV incentives across pools.

Additionally, holding veCRV grants eligibility for potential airdrops from partner projects, such as Convex—a CRV-staking and liquidity management platform—which allocated 1% of its CVX token supply to veCRV holders.

Clearly, CRV and veCRV fully capture protocol value—not only earning fee shares and boosted rewards but also wielding significant governance influence—thus creating strong demand and stable buying pressure for CRV.

Stablecoin issuers, driven by strong demands for peg stability and liquidity, almost invariably seek listings on Curve to establish liquidity pools and secure CRV emissions to maintain depth. Competition for weekly CRV emissions—allocated via Curve’s DAO module “Gauge Weight Voting”—requires users to vote with their veCRV to determine next week’s distribution ratios. Pools with higher weights attract more liquidity.

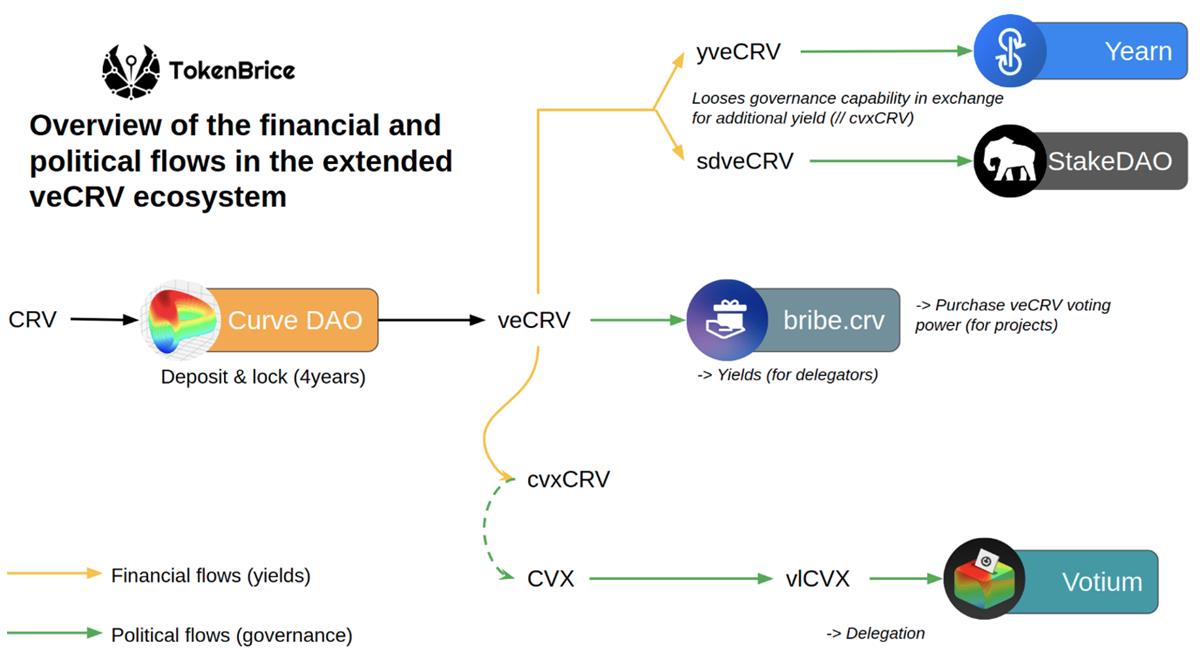

This silent war争夺“listing authority” and “liquidity incentive allocation.” **By gaining governance rights via CRV, these projects also receive stable dividend payouts from Curve as cash flow. The competition among projects on Curve generates sustained CRV demand, stabilizing CRV’s price despite heavy emissions, supporting Curve’s market-making APY, attracting liquidity, and creating a self-reinforcing cycle. Thus, the CRV wars have spawned a complex bribery ecosystem built around veCRV. As long as Curve remains dominant in stablecoin exchange, this battle will continue.

We summarize the clear advantages and disadvantages of the veCRV mechanism:

- Advantages

-

Reduced circulating supply due to locking reduces selling pressure, helping stabilize price (currently 45% of CRV is locked, average lock duration 3.56 years);

-

Better alignment of long-term interests (veCRV holders share fee revenues, aligning LPs, traders, token holders, and the protocol);

-

Time-weighted voting enables more meaningful governance.

- Disadvantages

-

Governance highly centralized—with Convex controlling 53.65% of voting power;

-

Underutilization of liquidity (boost and voting rights from locked CRV are non-transferable; although high subsidies attracted massive liquidity, much remains idle, unable to generate external yield);

-

Fixed long lock-up periods are unfriendly to investors—4 years is too long for crypto.

Innovations on the vetoken Mechanism

In previous writings by DODO Research, we detailed five innovations in veToken incentive design. Each protocol adjusts key mechanisms based on its own needs and focus. These include:

-

Designing veNFTs to improve vetoken liquidity;

-

Improving allocation of token emissions to vetoken holders;

-

Encouraging healthy liquidity pool trading volume;

-

Layering reward structures to give users choice.

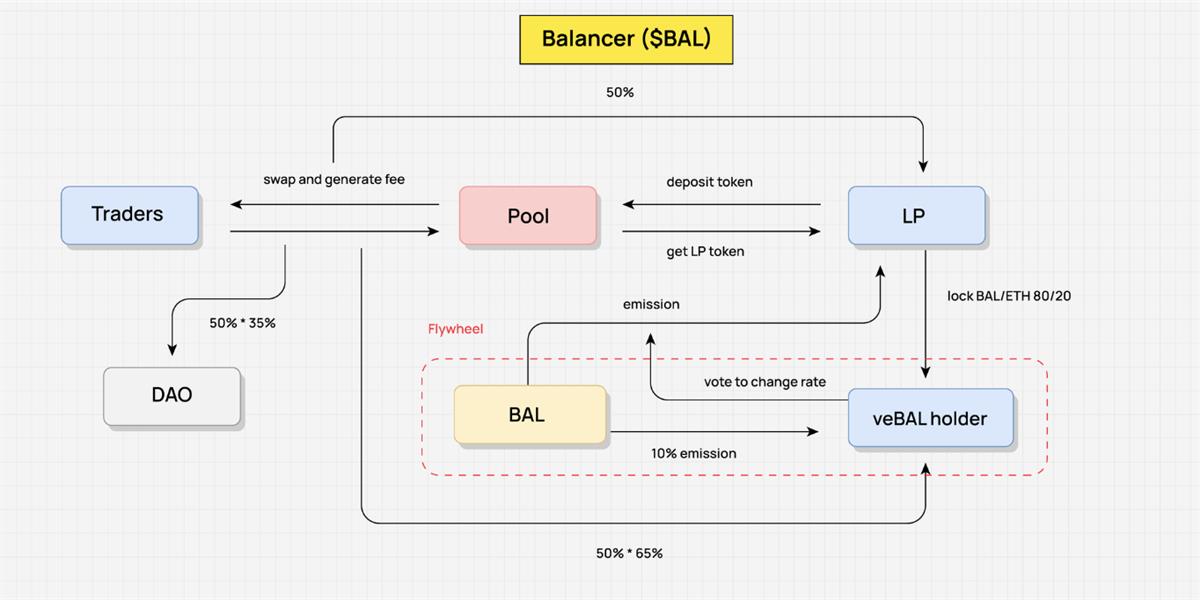

Take Balancer as an example. In March 2022, Balancer launched V2, revising its economic model. Users lock BPT (Balancer Pool Tokens) from the 80/20 BAL/WETH pool to obtain veBAL, tightly binding governance and protocol revenue rights to veBAL.

Users must lock both BAL and WETH in an 80:20 ratio instead of just BAL—**locking LP tokens instead of single tokens increases market liquidity and reduces volatility. Compared to Curve’s veCRV, veBAL has a maximum lock-up of 1 year and minimum of 1 week, significantly reducing lock duration.

For fee distribution, 50% of protocol fees go to veBAL holders in bbaUSD. Other benefits like Boost, Voting, and governance are similar to Curve.

Notably, to address the “wasted liquidity—no external yield generation” problem in vetoken models, Balancer introduced Boosted Pools—interest-bearing pools where LP tokens (bb-a-USD) can be paired with other assets in AMMs, leveraging positions to enhance LP returns. Later, Core Pools were introduced (to fix earlier Boosted Pools benefiting only LPs). By officially bribing veBAL holders to vote for Core Pools, large amounts of $BAL shifted toward them, increasing external yield-bearing assets and transforming Balancer’s revenue structure.

Velodrome: The Most Representative ve(3,3)

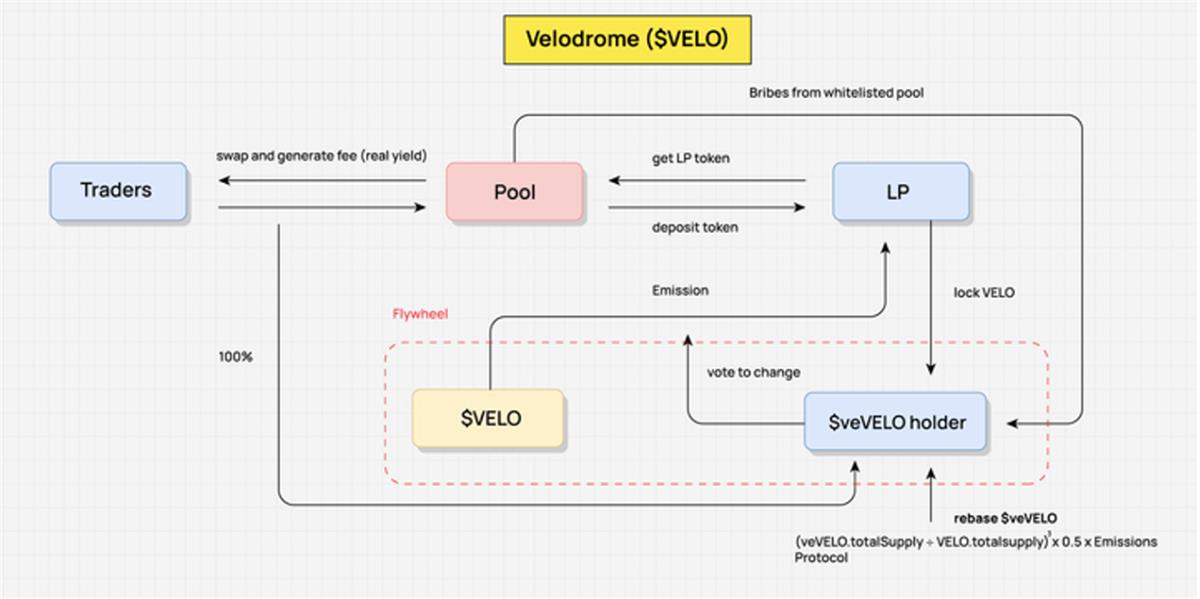

Before discussing Velodrome, let us briefly define ve(3,3): Curve’s veCRV economic architecture + Olympus’ (3,3) game theory.

As shown below, Olympus incentivizes OHM through two mechanisms: Bonding and Staking. The Olympus treasury sells OHM below market price via bonds, acquiring USDC, ETH, etc., to back the treasury. Newly minted OHM is then distributed to stakers via rebase. Ideally, if all users choose long-term staking—i.e., (Stake, Stake)—their OHM balances grow exponentially, creating a positive APR flywheel. But if secondary market selling pressure is severe, this flywheel collapses. Of course, this is a game—the ideal Nash equilibrium achieves mutual benefit.

Early 2022, Andre Cronje launched Solidly on Fantom, centered on veNFT and voting optimization. veSOLID positions are represented by veNFTs, freeing up liquidity—holders of transferred NFTs retain voting rights to allocate rewards. veSOLID holders receive a base share proportional to weekly emissions, maintaining voting power without new locks. Crucially, stakers get 100% of trading fees but only earn rewards from pools they’ve voted for, preventing curve-style voter bribery solely for rewards.

After AC announced ROCK tokens would be airdropped to the top 20 highest-staked protocols on Fantom, a vampire attack frenzy erupted among Fantom protocols—0xDAO and veDAO emerged, triggering a TVL war. Months later, the veDAO team incubated Velodrome, another ve(3,3) project.

Why did Velodrome and Solidly become standard fork templates on Arbitrum or zkSync and other Layer 2s?

In its original design, Solidly had key weaknesses: extreme inflation and fully permissionless access—any pool could claim SOLID rewards, spawning numerous meme tokens. Rebase or "anti-dilution" mechanisms added no real value to the system.

What changes did Velodrome make?

-

Implemented a whitelist mechanism for pools eligible for Velo emissions—currently application-based, not governed on-chain (avoiding vote-based token incentives);

-

Liquidity bribery rewards for pools are claimable only in the next cycle;

-

*(veVELO.totalSupply ÷ VELO.totalsupply)³ × 0.5 × emissions*—reduced emission rewards for ve token holders. Under Velodrome’s revised model, veVELO holders receive only 1/4 of traditional emissions. This significantly weakens the (3,3) aspect of the ve(3,3) mechanism;

-

Removed the LP Boost mechanism;

-

3% of Velo emissions allocated as operating expenses;

-

Exploring extensions of veNFT mechanics: veNFTs remain tradable even when staked/voting, can be split, and support lending;

-

More reasonable token distribution and emission schedule: Velodrome distributed 60% of initial supply to the community on launch day, partnering with Optimism to bootstrap cold-start momentum, and airdropped several protocols with veVELO NFTs unconditionally—greatly accelerating initial voting and bribery activity.

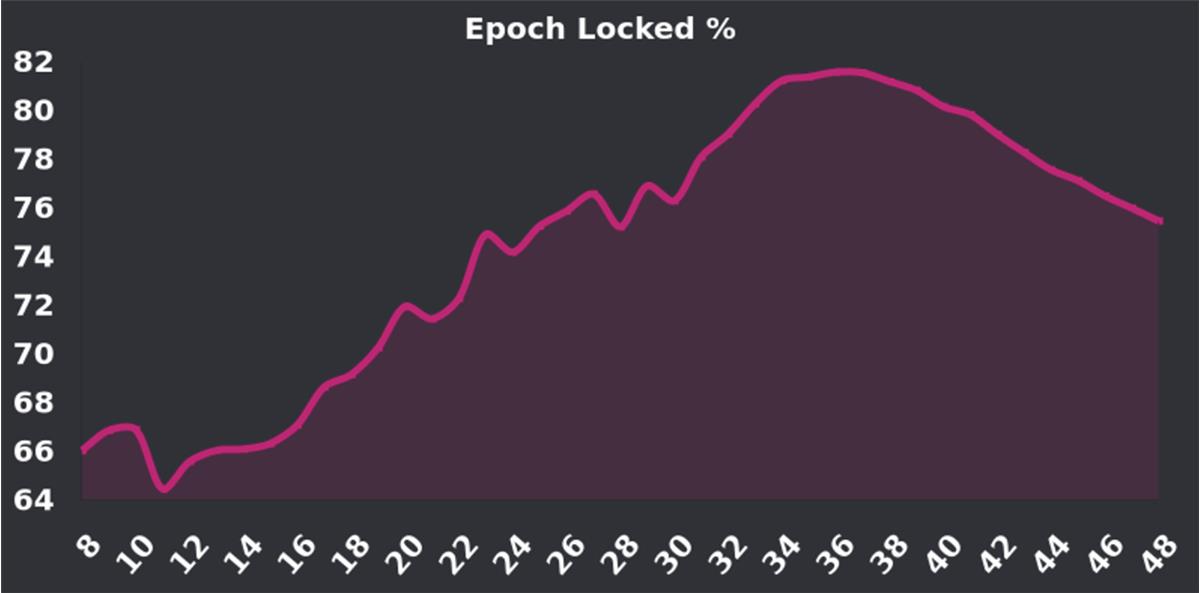

Post-launch, Velo staking rates rose steadily, peaking at 70%-80%—a very high lockup ratio (Curve’s current staking rate is 38.8%). Many questioned whether staking incentives would decline after November last year when the "Tour de OP" program ended and 4 million OP rewards ceased, potentially causing sell-off pressure. Yet, Velo staking remains strong (~70%). The upcoming V2 upgrade aims to further encourage token locking—worth watching.

V. ES Mining Model

ES: Playing Games with Real Yield, Incentivizing Loyal Users

The ES mining model is a fascinating and challenging new tokenomic mechanism whose core idea is to reduce protocol subsidy costs via vesting thresholds and enhance appeal and inclusivity by incentivizing genuine user participation.

Under the ES model, users earn ES Tokens through staking or locking. Although this makes yields appear higher, the presence of vesting thresholds means users cannot immediately realize these gains, making actual yield calculations complex and unpredictable. This adds both challenge and appeal to the ES model.

Compared to traditional ve models, the ES model has clear advantages in reducing protocol subsidy costs due to its vesting design. This brings the ES model closer to reality in the game of allocating real yield, making it more universal and inclusive, potentially attracting broader user participation.

The essence of the ES model lies in motivating authentic participation. If users exit the system, they forfeit ES Token rewards—meaning the protocol avoids paying additional token incentives. As long as users stay, they earn ES Token rewards, albeit non-immediately liquid. This design motivates real user engagement, maintains activity and loyalty, without over-incentivizing. By controlling spot staking ratios and unlock cycles, projects can craft more engaging and attractive token unlock curves.

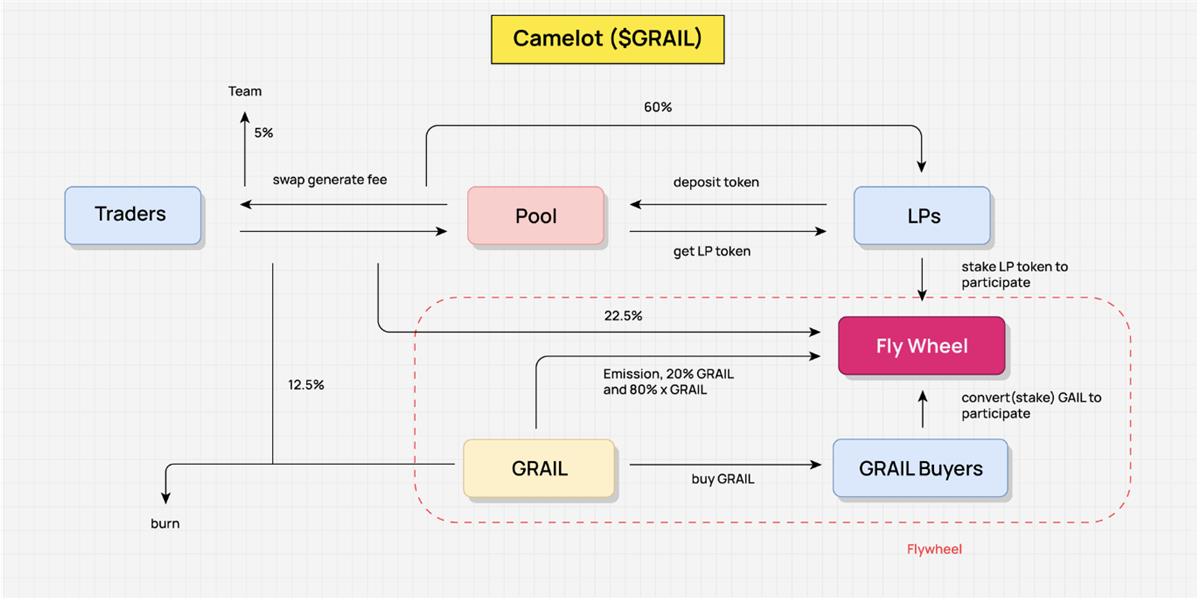

Camelot——Introducing Partial ES Mining Incentives

Analyzing Camelot’s value flow reveals how its tokenomics function. Here, we don’t detail every component but abstract the main value flows to better understand the overall framework.

Camelot’s core incentive goal is to encourage LPs to consistently provide liquidity, ensuring smooth trading experiences and ample liquidity. This design ensures transaction fluidity and enables LPs and traders to share generated revenue.

Camelot’s real revenue comes from trading fees generated by interactions between traders and pools. This is the protocol’s genuine income and primary source for redistribution—ensuring economic sustainability.

Regarding redistribution, 60% of fees go to LPs, 22.5% are recycled into the flywheel, 12.5% buy and burn GRAIL, and the remaining 5% go to the team. This mechanism ensures fairness and fuels continuous operation.

Moreover, this distribution drives the flywheel. To receive redistributed revenue, LPs must stake LP tokens—indirectly incentivizing longer liquidity provision. Beyond the 22.5% fee revenue, Camelot allocates 20% of GRAIL tokens and xGRAIL (ES tokens) as incentives. This not only motivates LPs but also encourages regular users to participate in revenue sharing by staking GRAIL, enhancing overall protocol activity and appeal.

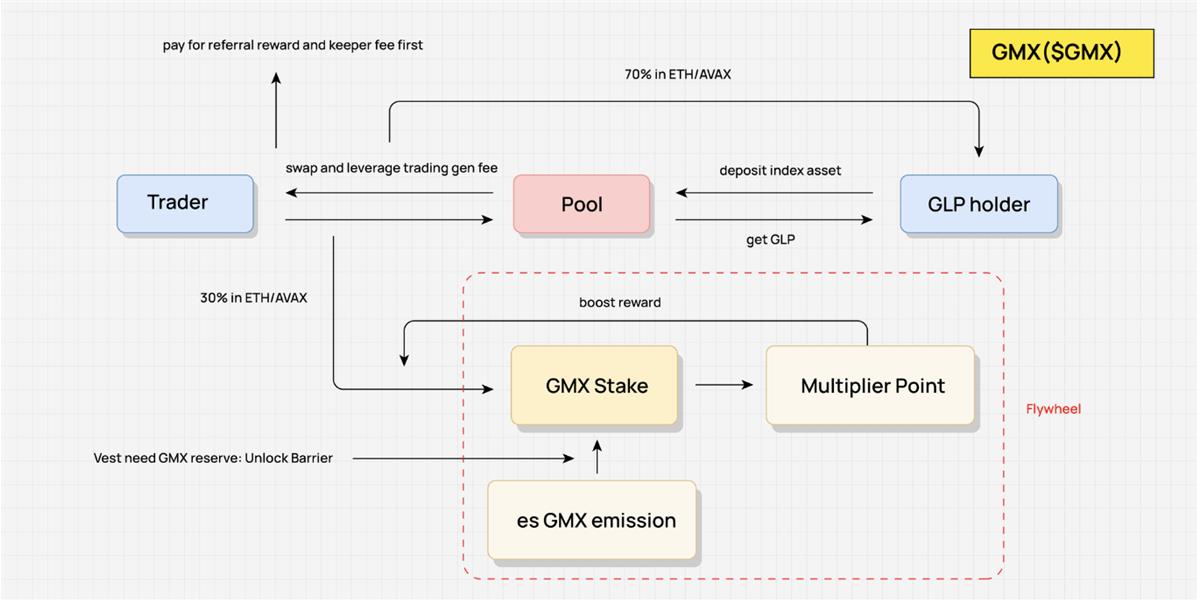

GMX——Incentivizing Competition for Real Yield Distribution

GMX’s tokenomics represent a highly engaging and interactive design, aimed at sustaining liquidity supply and encouraging continuous trading between traders and LPs. This design ensures protocol liquidity and volume while incentivizing long-term GMX staking.

Real yield comes from fees generated by swaps and leveraged trades—this is the protocol’s main revenue stream. First, referral and keeper fees are deducted. Of the remainder, 70% goes to GLP holders (i.e., LPs), and 30% is redistributed. GMX uses a game-theoretic mechanism to redistribute this 30%, forming the core of its model.

GMX’s core mechanism redistributes 30% of real yield. This portion is fixed, but GMX holders can influence their share through strategy. For example, users stake GMX to earn esGMX rewards, which unlock gradually upon continued GMX staking and meeting vesting requirements. Staking GMX also earns Multiplier Points—though non-withdrawable, they increase profit-sharing proportions.

In this mechanism, GMX, esGMX, and Multiplier Points all carry weight in profit distribution. The difference: Multiplier Points can’t be cashed out; esGMX unlocks slowly with GMX staking; GMX can be withdrawn quickly but resets Multiplier Points and forfeits future esGMX rewards.

This allows users to strategize based on goals. Long-term seekers maximize weight and relative returns by locking. Those exiting quickly can withdraw all staked GMX—unrealized esGMX stays in the protocol, so no actual subsidy is paid; instead, real yield is shared with the user.

Through this mechanism, GMX incentivizes GLP holders to sustain liquidity and fully leverages real yield redistribution. This makes long-term GMX staking feasible, reinforcing the model’s stability and attractiveness.

VI. Core Elements in DeFi Economic Model Design Through Value Flow

In DeFi economic model design, core elements include foundational value, token supply, demand, and utility. These components are somewhat fragmented, and past analyses often failed to integrate them intuitively. The Value Flow method used here abstracts internal value flows based on tokenomic mechanisms and product logic, providing a holistic view of value movement—including flywheel composition, revenue distribution paths, incentive layers—combined with token distribution and unlock schedules, offering an intuitive understanding of a project’s tokenomics.

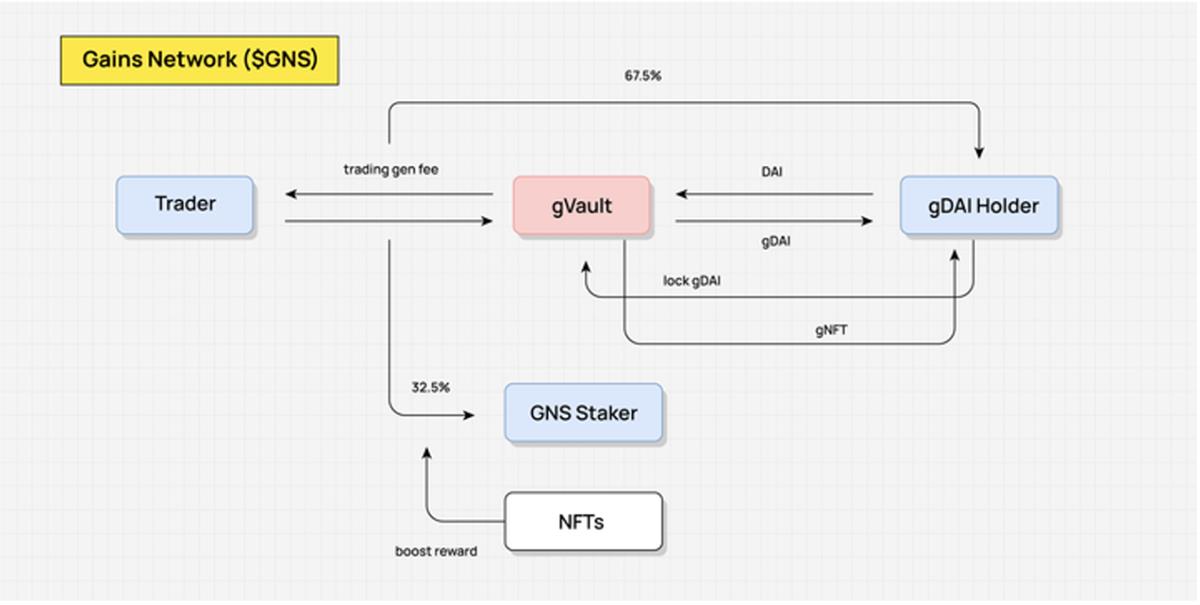

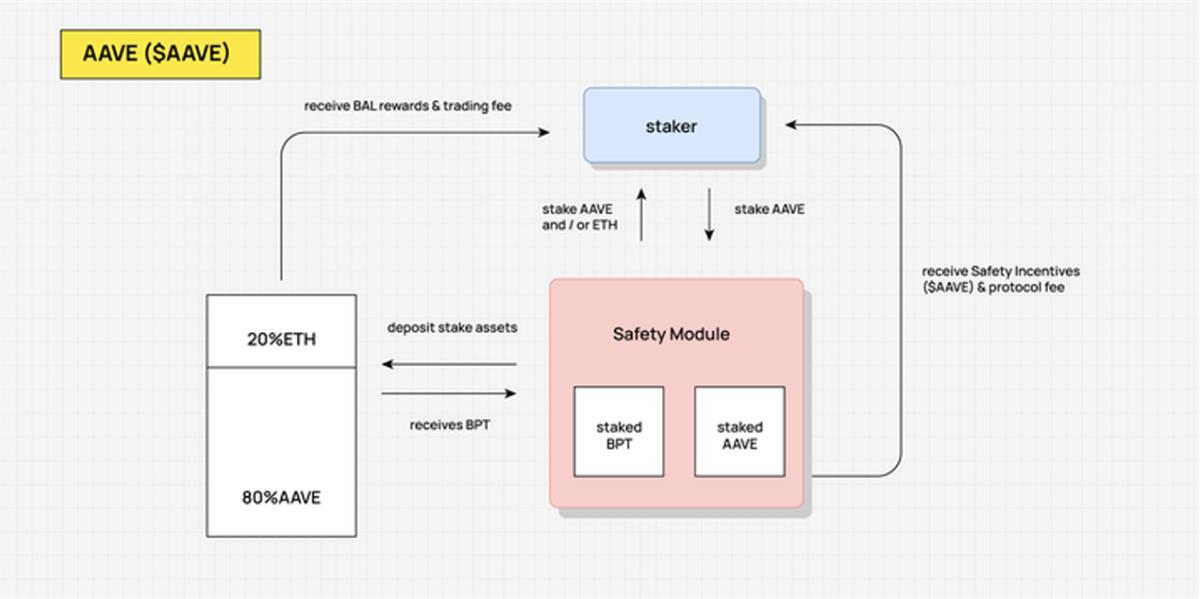

Below are Value Flow diagrams not detailed earlier due to space constraints:

GNS Value Flow (using NFTs to implement membership and redistribute revenue) Diagram: DODO Research

AAVE Value Flow (users stake AAVE to receive partial protocol revenue) Diagram: DODO Research

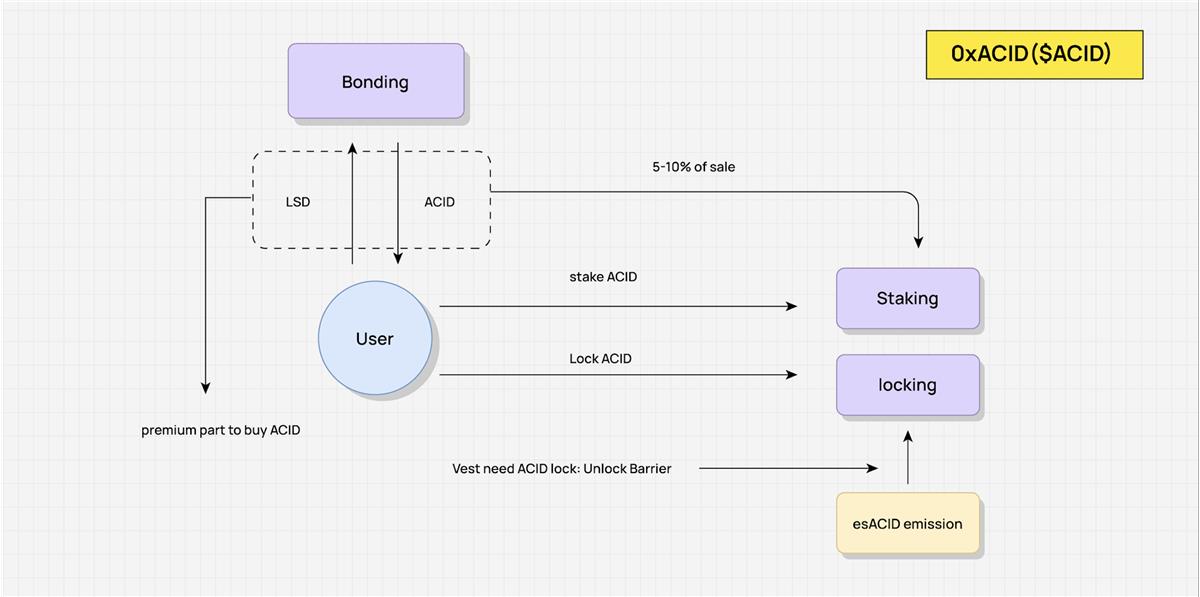

ACID Value Flow (combining es mechanism with Olympus DAO mechanism to power a flywheel) Diagram: DODO Research

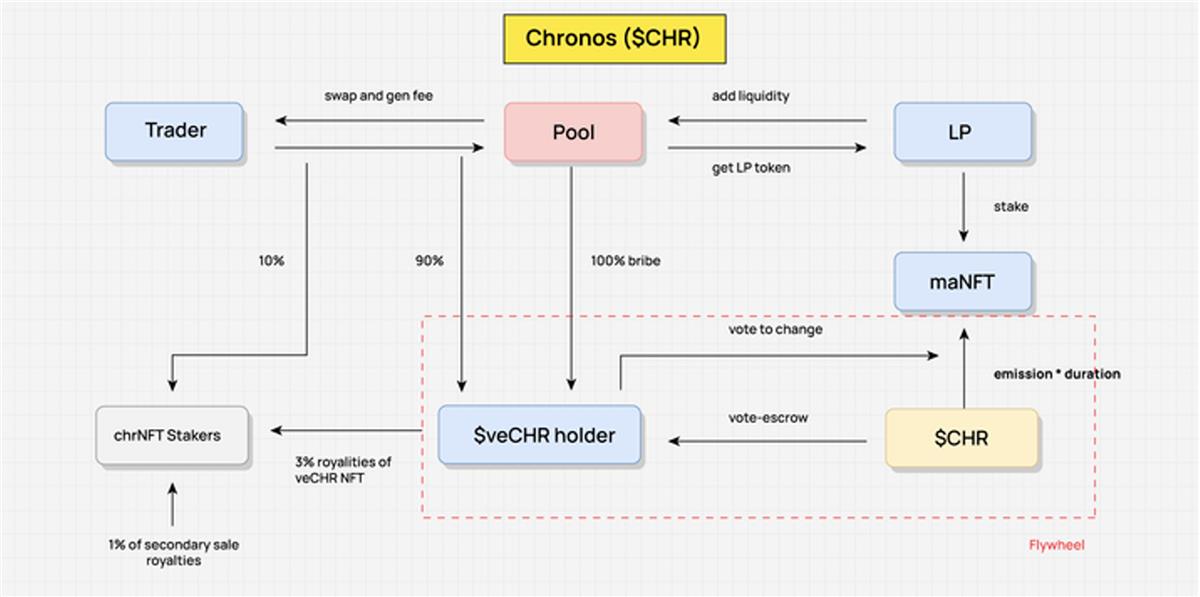

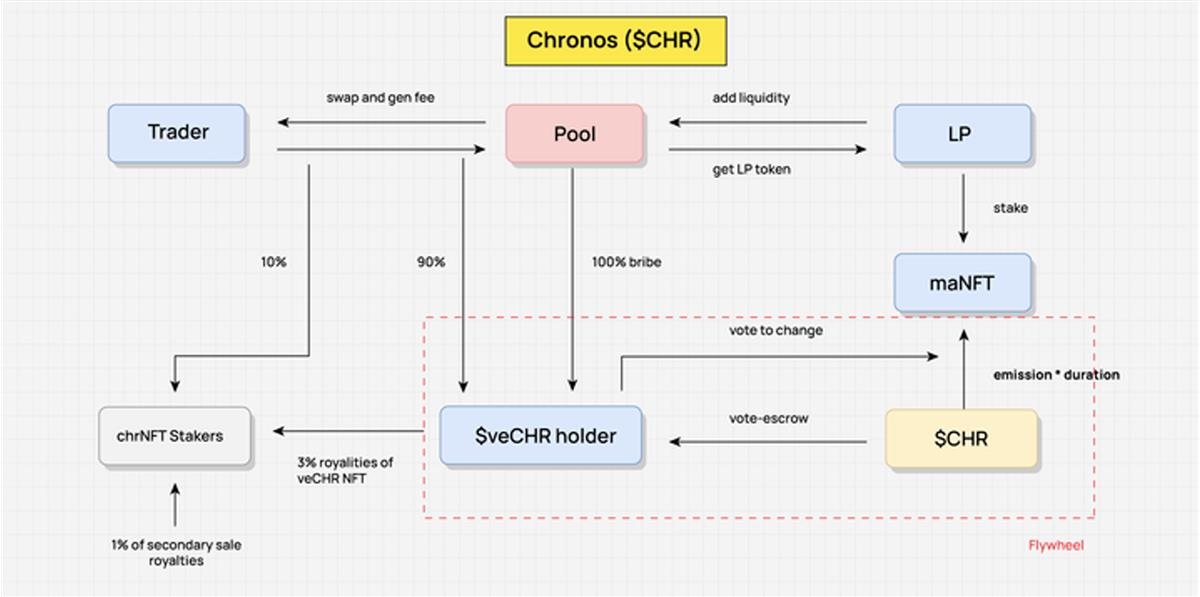

CHR Value Flow (ve(3,3) without rebase, preventing voting power concentration) Diagram: DODO Research

Structure of Value Flow

Most DeFi protocols generate real revenue—actual money flowing through the protocol, creating value.

Value Flow abstracts this intrinsic value movement. Starting from real revenue, it maps how revenue is redistributed. Then, it abstracts the direction and conditions of token incentives, clearly showing value capture, incentive points, and token flows. These flows constitute the entire business model, with token emissions being reallocated over time through Value Flow.

Take Chronos as an example. When abstracting its Value Flow, we first identify key stakeholders—Trader, LP, veCHR holder. These parties are redistribution participants and nodes of value flow—value moves among them according to designed mechanisms.

The key to abstracting Value Flow is mapping the flow and mechanisms of revenue redistribution—not detailing every step, but consolidating minor branches into a coherent whole. For instance, real revenue comes from trader fees, 90% of which goes to veCHR holders via the ve mechanism, incentivizing native token holding. Once abstracted, we clearly see how value moves within the protocol and evolves over time.

Value Flow isn't the entirety of tokenomics, but it captures the product-level value movement inherent in tokenomic design. Combined with initial token allocation and unlock schedules, it fully presents a protocol’s tokenomics.

Tokenomics Reshaping Value Flow

Why are early mine-and-dump economic models becoming rare?

Initially, tokenomic designs were crude—tokens seen merely as user incentives or short-term profit tools. These methods were simple and direct but lacked effective redistribution mechanisms. Take DEXs: when emissions and all fees go directly to LPs, there’s insufficient long-term LP incentive. Without other value sources, token prices easily collapse because LP migration costs are low, resulting in repeated broken liquidity mines.

Over time, DeFi protocols have refined their tokenomic designs—becoming more sophisticated and complex. To achieve incentive goals and regulate token supply/demand, various game-theoretic and revenue-redistribution models have been introduced. Tokenomics has become tightly coupled with product logic and revenue distribution. Reshaping Value Flow through tokenomics—redistributing real yield—has become its primary function. In this process, token supply and demand are regulated, enabling value capture.

Key Mechanisms in DeFi Tokenomics: Game Theory and Value Redistribution

In the later stages of DeFi Summer, many protocols improved their economic models—essentially introducing game-theoretic mechanisms to redistribute profits, thereby increasing user stickiness. Curve redesigned its token reward mechanism, using voting to redistribute emissions, spawning bribery economies and compositional platforms. Another core aspect of tokenomics is using additional token rewards to spin the flywheel, capturing more traffic and capital.

In summary, under such mechanisms, tokens are no longer mere mediums of exchange—they become tools for user acquisition and value creation. This profit redistribution process not only boosts user activity and retention but also stimulates participation and drives system-wide growth through token incentives.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News