Seed-stage Founders' Essential Course: It's You Who Tells the Story, Not the PPT

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Seed-stage Founders' Essential Course: It's You Who Tells the Story, Not the PPT

Compilation of notes shared with a startup founder seeking funding.

Author: JOEL JOHN

Translation: TechFlow

This article was inspired by a conversation I had with Joe Eagan of Anagram about their EIR program, and it compiles notes I shared with a startup founder seeking funding.

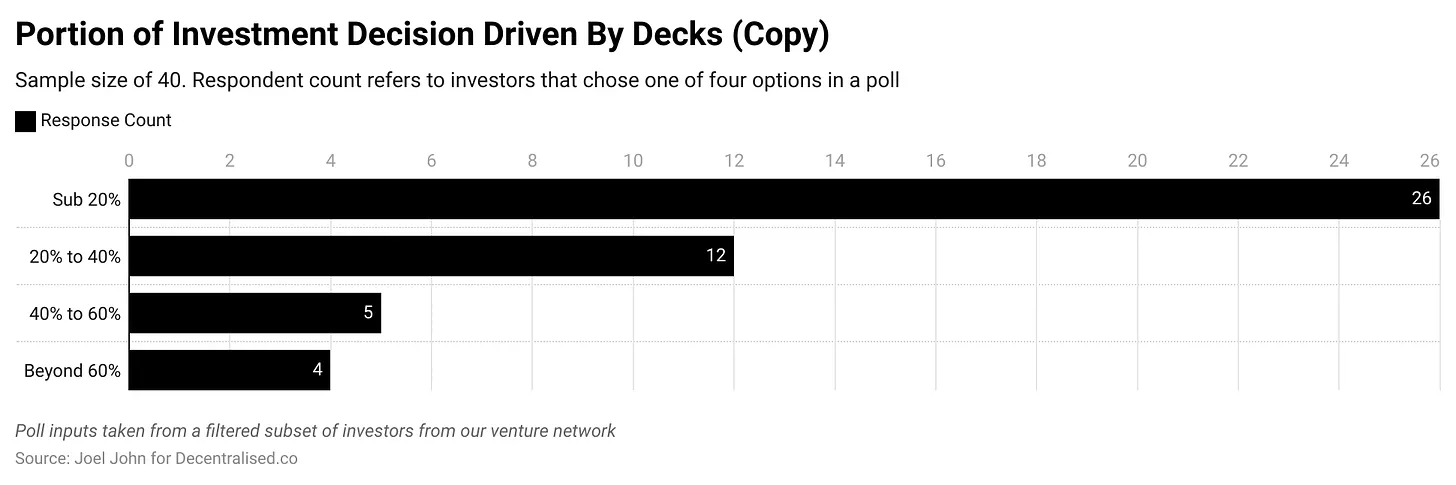

The Importance of Signals

Before writing this piece, I asked two groups of investors the same question: “How much of your seed-stage investment decision is driven by the pitch deck?” Answers varied. Dovey Wan from Primitive Ventures pointed out in our venture capital community that seed investing is like a first date—it’s mostly about vibes. Kyle Samani of Multicoin believes most fundraising is about communication, and the pitch deck is the primary tool for conveying that.

At the seed stage, there's usually very little information about the product. If it's a new market without existing competitors, data on market size is also extremely limited.

When investing in Amazon in the late 1990s, did investors focus on the market for online book sales? Or on Jeff Bezos leaving his position as a vice president at D.E. Shaw? The former might have seemed promising, but the signal was weak.

However, a hedge fund manager giving up a comfortable job to analyze the frontier of the internet to minimize regret—that’s a very strong signal.

Founders can build signals in many ways. Y Combinator’s Jessica Livingston recently noted that what intrigued her about the Airbnb founders was their hustle. To extend their runway while drowning in credit card debt, they created $40 boxes of cereal. These politically themed cereal boxes helped them earn $30,000 during an election year. At one point, they were trying to give up 6% of their company for a $20,000 check.

Airbnb is now valued at $96 billion.

I'm not suggesting founders should start selling cereal. What makes the Airbnb story impressive is that they didn’t shut down their bed-rental business to sell political cereal. A 2024 crypto equivalent might be a founder launching a platform to kickstart a politically themed meme coin.

My point is, at the early stage, venture capitalists are looking for signals. And these signals can be generated in various forms. At the seed stage, when you have nothing else to show, the pitch deck is just one way to create such signals.

But what do you do when you don't have a pitch deck? You could spend 100 hours perfecting your presentation, or you could build those signals in several other ways.

Tell Your Story Well

Many companies are built through excellent communication. One of my favorite examples is Anand Sanwal, founder of CB Insights—a company offering market intelligence and data analytics. You may not know him, but most venture analysts rely on CB Insights for market maps and early insights into emerging sectors, such as AI-driven agriculture or robot-powered food delivery.

A good example of his storytelling ability is how he framed life challenges, compared his father’s business with CB Insights, shared lessons learned from running a SaaS company via slide decks, or even joked about his startup’s original name being “Chubby Brains” (here).

For seed-stage founders, one of the highest-return activities is spending 8–12 hours compiling everything they know into a GitBook. This document should deeply explore the nuances of an emerging industry (like intent or Passkeys), the market opportunity, and how their product fits in. You can go deep here—something you might not do in your pitch deck.

In nascent industries, a well-crafted document can become the go-to research resource for analysts. That way, VCs come to you instead of you cold-messaging them. More importantly, potential employees, partners, and media will also rely on these documents. A well-written doc is a bridge inviting the public to dream with you—a foundation for building community and leveraging network effects.

Of course, not all founders want to spend time writing docs. So what else can you rely on? Another method is telling a compelling story. For instance, read this summary of Peter Thiel’s class notes:

“The founding team of PayPal consisted of six people, four of whom built bombs in high school.”

That sentence instantly grabs attention and shows how these individuals came together to pursue a digital currency dream. A story is an entry point, and the narrative style can vary. Too often, I see founders playing a role, hoping VCs won’t regret missing them.

Strong founders understand this. Steve Jobs once deliberately hid his Porsche when VCs visited because he didn’t want them to think he was already wealthy.

Founder stories often stem from childhood experiences, consumer pain points, or workplace observations. Jeff Bezos famously left his comfortable hedge fund job because he saw the massive potential of the internet. Vitalik’s experience of losing assets in World of Warcraft is often cited as a reason for his interest in decentralized asset ownership.

Your story can be shared through any medium you prefer—podcasts, tweets, short videos, or articles. It doesn’t matter. What matters is sharing it so people can get to know you. At the seed stage, the most compelling stories are often personal ones, because investors are typically betting on the founder. You should share your story because consumers may embrace it before investors do. When consumers resonate with your story, you gain market traction. Which brings me to my next point.

Doing Things That Don’t Scale

A better alternative is to launch an imperfect product and find early users. If you release a flawed product, you’ll likely receive painful feedback from customers—which can help you iterate. These early users become powerful references when VCs consider backing you.

Below is a private message I sent to Alex from Nansen back in 2020, after spending $7 on their product. He personally provided one-on-one customer support. In the early days, their product was just a simple SQL dashboard. Today, they’re valued at $750 million. I’m proud to be an investor. But before that, I was a satisfied customer—even though the product had many flaws. I stuck around because whenever issues arose, Alex personally stepped in to help—and he still does.

Telling your story and focusing on your customers costs nothing—but it could be the difference between success and failure.

That December, I even wrote an article about Nansen. If you're a user, compare the screenshots in that post with today’s product to see how far they’ve come. Being a decent human and building interesting things is the most cost-effective way to get free publicity.

Many founders raise millions yet build things nobody needs—because their core customer becomes the VC who wants to invest. They’re selling equity, not their own product. And since capital allocators are often incentivized to stay “friendly” to maintain deal flow, they rarely give honest feedback. The market is usually the final judge of whether your goal is to create something desirable.

Early enthusiasts aren’t looking for fully polished products. If you care for them or deliver meaningful value, early adopters will use a flawed product.

Too often, consumers choose based on which founder pays attention to them. If you don’t have the best product, simply spending time talking to potential users can compensate for a subpar early experience. People want to be heard before they’re served. Paul Graham called this “doing things that don’t scale.”

Formation of Consensus

Much of venture capital operates on consensus. As a VC, you don’t actually focus much on TAM, revenue, or even the founder. Because if TAM is large, you’re either betting on a mature market with limited upside or lacking focus.

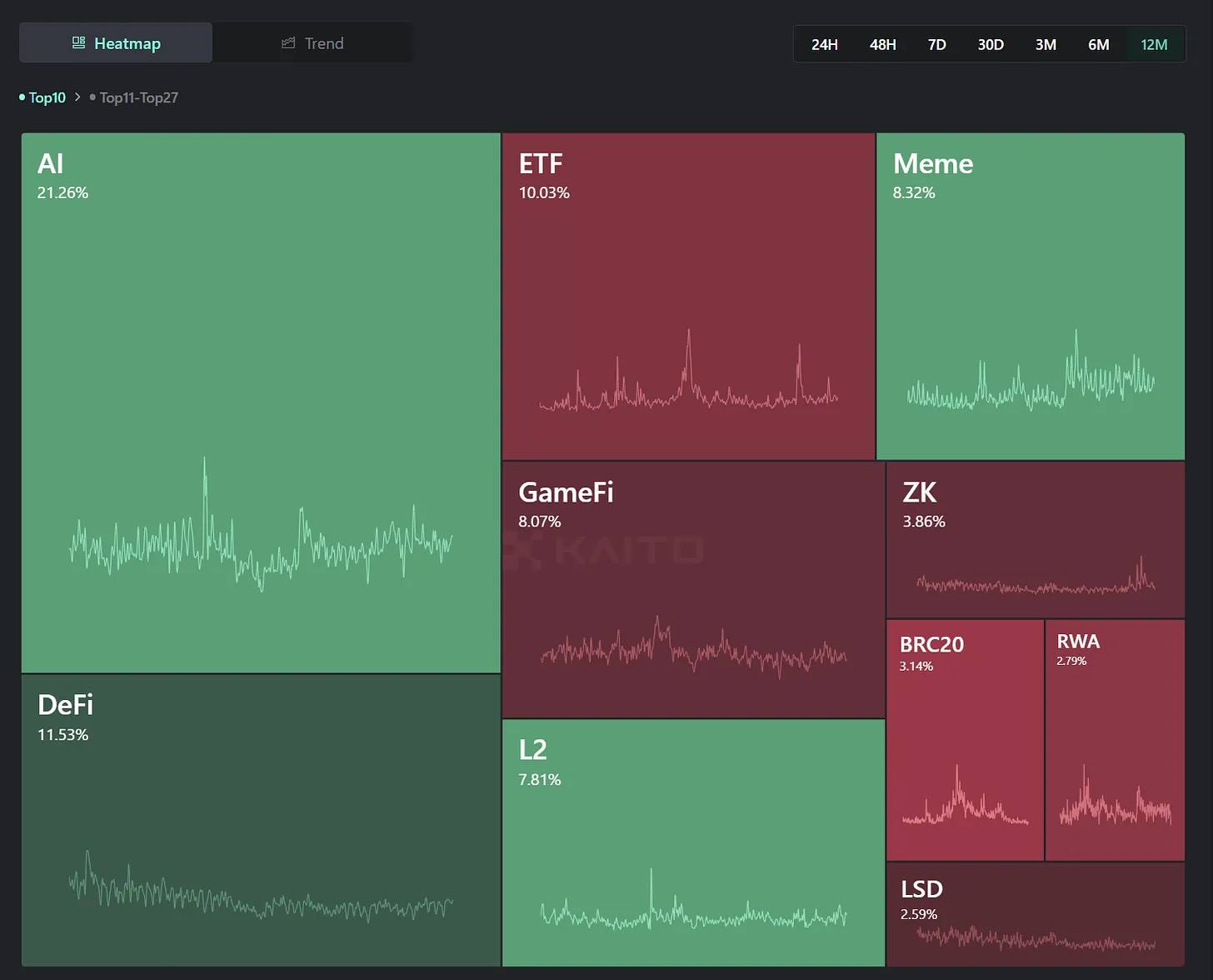

Instead, early-stage VCs care more about what buyers in later rounds (other VC funds) will bet on. The focus tends to be on narratives or themes.

This is both a strength and a weakness. The strength is that visionary VCs can guide founders toward market opportunities they might have missed. The downside is that only projects aligned with what follow-on investors care about get funded.

Founders solving hard problems often struggle to find backers because the exit path for VCs may be unclear. In crypto, M&A is rare. Most crypto VCs rely on token models. When you know the market depends on preset narratives, you optimize accordingly.

In traditional VC, achieving an “exit” typically takes ten years. If you last that long, your odds of success are around 10–15%. In crypto, the token cycle is 24 months.

This raises the bar for founders tackling hard problems. These often involve consumer-facing applications requiring deep market understanding and technical problem-solving.

As a seed-stage founder, how do you navigate this? Truthfully, it’s hard. Some founders excel at storytelling, but most don’t. Even if you have market appeal, the market may not assign you the valuation you expect. Google nearly sold itself for $750,000—this isn’t new.

A company’s valuation is the collective fantasy of founders and supporters about its future potential. Sometimes only the founder has this fantasy; sometimes every fund shares it (like we did with FTX). The number of capital holders who share this fantasy determines seed-stage valuations.

When consensus hasn’t formed in an industry, success often comes down to persistence. The startup world is full of founders who kept going until a fund finally backed them. Canva’s founders were rejected 100 times. Only in Web3’s hyper-capitalist world, where token exits are assumed, do we see rounds fill overnight.

As long as venture capital relies on consensus and crypto relies on token liquidity, founders solving hard problems will continue to face fundraising difficulties. That’s the nature of the game. If you’re a founder committed to solving tough problems, don’t treat rejection as a measure of your work’s value. Often, you’re conveying a vision only you can see. If it were a consensus bet, you’d be in a crowded market. But there are subtle differences.

Just because you keep building in a market doesn’t guarantee success. Smart founders usually know when to double down and when to shut down. Many founders we’ve worked with closed their companies, took a break, then re-entered the market after learning from past experiences. These founders are often held in higher regard for the lessons they’ve gained and the integrity they showed in shutting down unsuccessful projects.

Shutting down a company is just as commendable as persisting. Often, the value lies in having honest conversations along the way.

Shuffle

(Reference source: link. By the way, this might be because he's been doing it for over twenty years.)

I wish I could tell you the pitch deck doesn’t matter. But I’m not Masayoshi Son running SoftBank—I’m just helping out at Decentralised.co.

Ultimately, the pitch deck serves a simple purpose: to convey the information the founder needs to share during fundraising. Most founders struggle with storytelling, community-building, or achieving ramen profitability. So the pitch deck becomes the lowest barrier to entry.

Therefore, assuming you’re still determined to succeed, I suggest ignoring most of the garbage advice from investment bankers. In 2015, VCs spent an average of 3 minutes and 44 seconds on a project. By 2024, your window shrinks to 2 minutes and 30 seconds. In crypto, you may only have one minute, because the analyst or partner reviewing your deck is probably watching a meme coin price chart at the same time.

Here’s what you should include in your pitch deck:

-

The nature of the opportunity and your unique approach to it.

-

Why your team is uniquely qualified—including background, story, and personal factors.

-

Signs of market pull: customers you already have, sign-ups, pre-orders—evidence supporting demand.

-

You need to identify ways to improve unit economics to scale—i.e., what kind of viral factor gives your product a competitive edge.

-

How the product makes money. You don’t need a definitive answer, but you must show directional clarity on the scale at which it becomes profitable.

-

If you already have customers, consider showing proof of their love—tweets, email replies, chat logs. Display real user feedback.

This is what I wish a founder friend knew. A perfect pitch deck is like the perfect cup of coffee I chase as a writer. You can wait and assume things will work out. But like coffee, a pitch deck won’t solve everything.

A pitch deck can become a procrastination haven. Accelerators like Y Combinator work partly because they set application deadlines. Founders are forced to submit half-baked ideas. Yet, over a ten-year horizon, YC founders have had the biggest impact across the network.

Instead of waiting for the perfect presentation, talk to customers, cold DM VCs, launch your product. Most of these attempts will fail—rejection is normal for early founders. But you can’t rally a team around a vision in your head. You need something tangible. The best way to achieve that is through conversations. Instead of spending weeks on a pitch deck, engage with people, record feedback, and ship fast—this path offers a far greater chance of success.

Like coffee and writing, the pitch deck exists to serve you—not the other way around. If you have a better way to convey credibility, delay perfecting the deck.

Here are some resources to help founders build their pitch decks:

-

A collection of over 1,400 pitch decks for inspiration.

-

Y Combinator’s slides for those who prefer a standardized format.

-

Some additional pitch deck examples.

-

NFX’s article on storytelling (my personal favorite).

-

OpenDeck—pitch decks categorized by business model and stage.

-

NYU professor Ashwath Damodaran’s lecture on numbers and storytelling.

-

And my article from last year on the narrative game.

-

If you want to step outside the startup world for pure inspiration, check out this book on creativity.

Seed-stage investing is fundamentally an investment in people. VCs buy access to a founder’s network and experience at a low valuation. If a founder lacks these, documentation can showcase their expertise. Ultimately, all early-stage investments are bets on the founder and their ability to scale the company.

Still, there’s a caveat: founders need to operate in domains favored by capital. Today, building and raising for an NFT marketplace is far harder than it was 36 months ago, as attention and capital have moved elsewhere.

In a world of scarce attention, capturing attention is half the battle. How you do it is up to the founder.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News