Crypto Valuation and Financing in the Bubble Cycle: A Life Game About Timing

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Crypto Valuation and Financing in the Bubble Cycle: A Life Game About Timing

Good timing trumps everything, and luck is also part of strength.

Author: Howe

This article builds upon Nanjie's seminal piece, "How Do Web3 VC Fundraising and Valuations Work?", with additional insights and expansions.

It is recommended to read the original article first. I will do my best to explain my views in simple and accessible terms.

1. Fundraising and Valuation Process

We need to first categorize VCs into three types: VCs with lead investment capability, VCs capable of leading but not acting as lead, and VCs without lead investment capability.

In a project’s fundraising and valuation process, influence is distributed as follows: VCs with lead investment capability >> VCs capable of leading but not leading ≈ VCs without lead investment capability.

Additionally, the earlier the funding round in which a VC leads, the greater their influence. Based on my observations of project fundraising, lead VCs typically only appear in the first two funding rounds. Subsequent rounds are usually either strategic investments or standard rounds without a lead investor.

Why is this the case?

The biggest challenge an early-stage project faces in fundraising is—where to find capital? Most project teams have very limited channels to pitch to investors—either through personal connections, FAs (financial advisors) introducing them to VCs, or help from angel investors.

When a VC with lead capability participates in an early round, they often take on an advisory role beyond just providing capital. Internally, they assist in refining narratives, revising pitch decks, designing tokenomics, and structuring financing terms. Externally, they connect with other VCs, introduce partnership opportunities, and provide endorsement for marketing activities.

The caliber and standing of the first lead VC essentially determine the ceiling of the project. VCs capable of leading but not leading, along with those without such capability, typically only contribute capital—though the former may occasionally offer additional resources. Therefore, project teams must carefully choose their lead investor partners at this stage.

After classifying VCs, we also need to distinguish between projects in existing sectors and those in entirely new sectors.

Valuation for projects in existing sectors is relatively straightforward. It generally involves setting a ceiling based on the sector’s total market cap relative to the overall market, then benchmarking against the market caps of the top one or two projects in that sector. If the project has additional negotiation leverage, the valuation multiple can be increased accordingly.

Valuing projects in completely new sectors is far more uncertain. Typically, only the most prominent lead VCs enter such projects early, using a set of "standards/data/processes" to initially price the sector before assigning a specific valuation to the project.

Early-mover projects often enjoy some valuation premium, as higher pricing within reasonable expectations can help expand market scale (and bubbles), assuming the sector isn’t invalidated.

Frankly, I believe no matter how much analysis you do, it's extremely difficult to arrive at a reasonable valuation range for a new sector in its early stages. You mostly have to proceed step by step, gradually adjusting your estimates.

Why is this kind of sector valuation analysis primarily done by top-tier lead VCs? Can other VCs do it too?

The answer is yes—but it doesn't matter. Such analysis requires access to sufficient and accurate market information, where top-tier lead VCs hold a significant advantage (akin to apex predators in an ecosystem).

Other VCs may attempt it, but without adequate information sources, they’re unlikely to produce reasonable or accurate results. Thus, most simply follow what the "top dog" says.

2. How Project Teams Determine Their Own Valuations

This section aims to demystify the process. You might think valuations are derived from careful calculations and research, but in reality, such cases are rare exceptions. More often:

➣ Look at competitors’ fundraising data and tweak the number up or down arbitrarily.

➣ Are misled by early-investing VCs who want more allocation, while naive project founders comply (a common trap for first-time entrepreneurs).

➣ Overconfident, especially during bullish market conditions, leading founders to inflate valuations recklessly.

➣ Blindly follow the lead VC—the "paymaster" decides everything.

……

In many cases, project teams themselves struggle to make sense of their own financials. The saying “the world is a giant makeshift troupe” holds more truth than ever.

As one of China’s earliest venture capitalists, Zhuang Minghao, once noted, most investment and valuation decisions are “black boxes.” There isn’t necessarily a mature methodology or logic guiding VCs before investing. You can always rationalize it in hindsight, but rarely predict it accurately beforehand.

I highly recommend watching @HanyangWang's video, "Zhuang Minghao: Is There a Methodology Behind VC Investing? Decisions, Regrets, Taste, and Stories from the Chaotic Early Days of Mobile Internet", which complements my earlier article "VC Evolution Trilogy: The Arbitrage Chronicles".

It offers additional perspectives on how VCs operate (I may write a separate review later if the opportunity arises).

3. How Important Is It to Analyze Fundraising and Valuation?

In my view, it varies—it can be important, but shouldn’t be taken too literally. Zhuang Minghao’s analogy about the process is particularly fitting.

VC investing, especially in early stages, resembles ancient rain-making rituals. Looking back, we know these rituals had no scientific basis. Yet why did so many civilizations across history practice similar rites? Because humans seek certainty amid extreme uncertainty, repeating actions that seem to yield results. If something works—even partially—it gets reinforced as ritual. To put it bluntly, or more directly, this ritual reflects a fund’s taste/preferences/strategy.

This process involves countless factors of timing, environment, people, and luck—highly unpredictable.

For example, when ancient people performed rain rituals and coincidentally experienced rainfall due to sea winds carrying moisture that cooled and condensed locally, they mistakenly attributed success to the ritual, placing hope in randomness.

Let’s take an industry example: In 2021–2022, during the bull market with abundant liquidity and a booming NFT sector, OpenSea was valued at over $10 billion. Was this valuation arrived at through rigorous analytical methods by VCs? Did any VCs think it was expensive at the time? In reality, most VCs were simply afraid of missing out—they didn’t care whether the valuation was reasonable or high (don’t assume VCs are immune to FOMO).

OpenSea Funding History

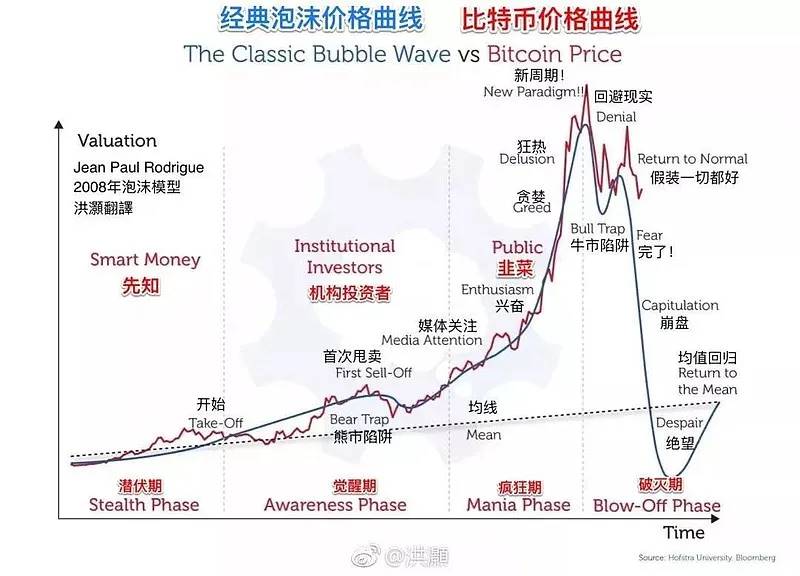

The so-called perfect alignment of timing, environment, and people essentially corresponds to the theory of bubble cycles. Different phases of the bubble cycle reflect varying levels of market liquidity and sentiment, which cause deviations in fundraising and valuation—FOMO inflates valuations above normal levels, while FUD suppresses them below.

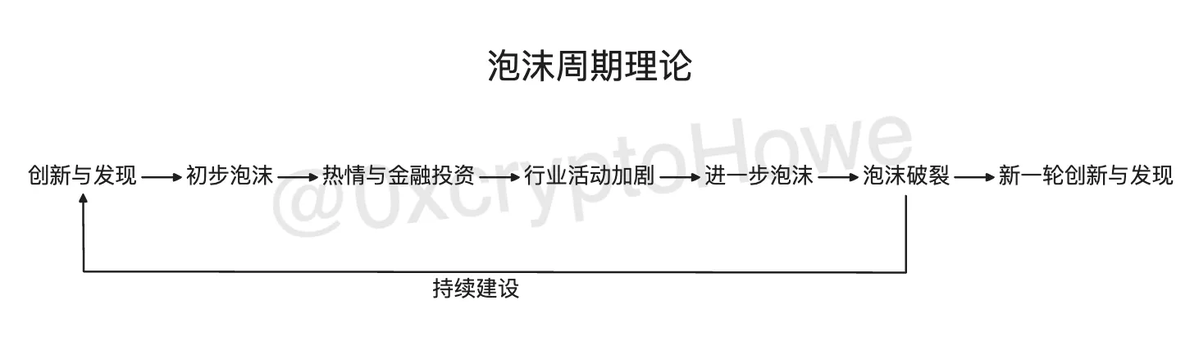

Bubble Cycle Theory

There’s another interesting phenomenon—some VCs or investors, in hindsight, appear to have followed highly instructive logics in certain sectors. But did they actually profit from those strategies? Not necessarily. Most didn’t earn much (this feels like self-criticism).

Sometimes, all the theory in the world can't beat entering at the right moment.

History repeats itself. When you look back at the past two investment cycles, the pattern generally looks like this:

4. Additional Thoughts Based on the Original Article

This section presents personal opinions on parts of Nanjie’s original text, offered for reference only.

-

Number of projects across different “valuation / fundraising” tiers

Outliers in the data should be removed—for example, OpenSea’s $10 billion valuation mentioned earlier. These special cases significantly skew results and lack meaningful reference value.

Such projects are often over- or under-valued due to market emotions like greed or fear, deviating from normal market sentiment. They should either be excluded or analyzed separately.

-

Impact of funding round stage on “valuation / fundraising” multiples

From what I’ve observed, most crypto projects undergo 3–4 funding rounds or fewer. Beyond that, additional rounds offer little benefit. Only major infrastructure projects from early cycles or category leaders during bull-market FOMO periods exceed this number.

Most projects launched in recent years don’t surpass this count. If a project raises capital over many rounds, it likely spans an entire market cycle (bull and bear). Unless the team keeps pivoting and finding new VCs to offload onto retail investors, I can’t imagine another plausible scenario.

-

Impact of funding year on “valuation / fundraising” multiples

This essentially ties back to the bubble cycle theory—FOMO intensity varies across periods. You’ll also notice that crypto’s红利 and liquidity are trending downward.

The ICO wave in 2017, DeFi Summer in 2021, the inscription ecosystem in 2023, and the meme coin surge in 2024—each macro wave carries less liquidity than the last. The overflow of market liquidity continues to shrink. The era of massive flooding and universal revival is unlikely to return; at best, we’ll see scattered bright spots.

Based on current trends, I believe the past decade-plus of crypto development constitutes a complete bubble cycle. With increasing regulatory clarity over the past two years, we’re likely entering a new cycle of innovation and discovery. I look forward to the opportunities ahead.

-

Relationship dynamics among project teams, VCs, exchanges, and retail investors under different market conditions

There are many possible scenarios here. Each party has hidden motives, but all share one goal—to maximize their own利益. Achieving this can take many forms, forming a vast and evolving ecosystem.

If you could fully understand this ecosystem map, you’d gain clarity on many things—like who profits from what—and better identify your own path and revenue model. Sadly, I myself only grasp fragments of it.

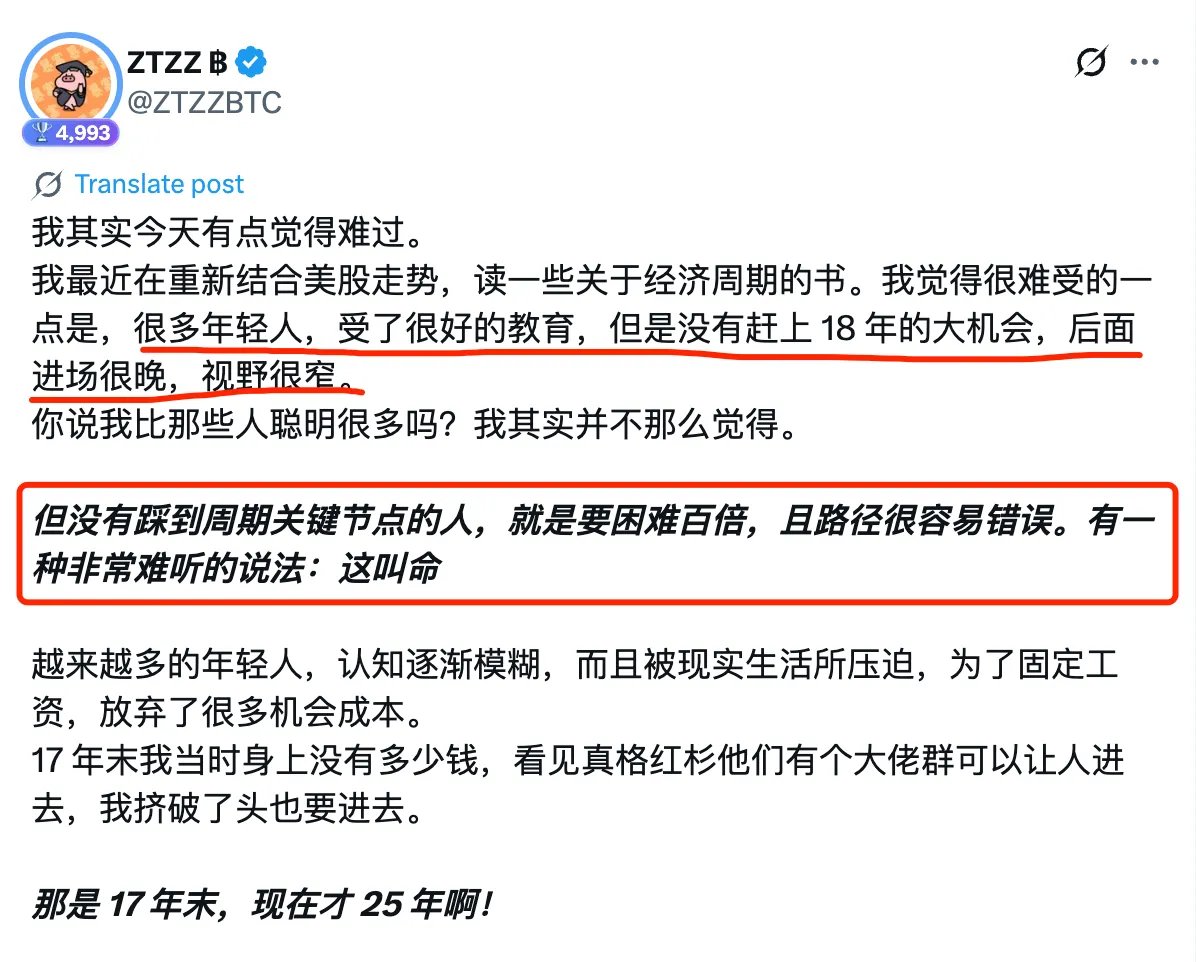

That said, after nearly two and a half years in the space, I’ve realized that timing trumps everything else. Luck is part of skill.

ZZ teacher has pointed this out too—entering the right industry at the right time means money is practically picked up off the ground. Yet often, such individuals’ understanding doesn’t match their asset size. Take the recent case of a user losing around 4 million RMB due to buying a hardware wallet from JD.com. Someone unaware of basic survival rules in the dark forest possessing such wealth confirms that choice outweighs effort.

https://x.com/ZTZZBTC/status/1948687136322191450

Finally, I wish everyone the ability to seize their own opportunities. Slow is fast. Many things aren’t as sophisticated as they appear. Demystification is the path to better profits. Let’s keep learning together 🫡

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News