FHE is the next step for ZK, says encryption technology

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

FHE is the next step for ZK, says encryption technology

Application scenarios and real-world implementation are the breakthrough for FHE to become blockchain infrastructure.

Author: Zuo Ye

The development trajectory of cryptocurrency is exceptionally clear: Bitcoin created cryptocurrencies, Ethereum created public blockchains, Tether created stablecoins, and BitMEX invented perpetual contracts. These four innovations—like cryptographic primitives—have built a market worth trillions, spawning countless rags-to-riches legends and the enduring dream of decentralization.

In contrast, the evolution of cryptographic technology remains obscure. Despite various consensus algorithms and elegant designs, nothing has proven more foundational than staking and multi-signature systems—the true pillars underpinning cryptographic infrastructure. For example, without centralized custodial WBTC, most Bitcoin Layer 2 solutions would collapse. Babylon’s native staking represents an exploration in this direction—an exploration valued at $70 million.

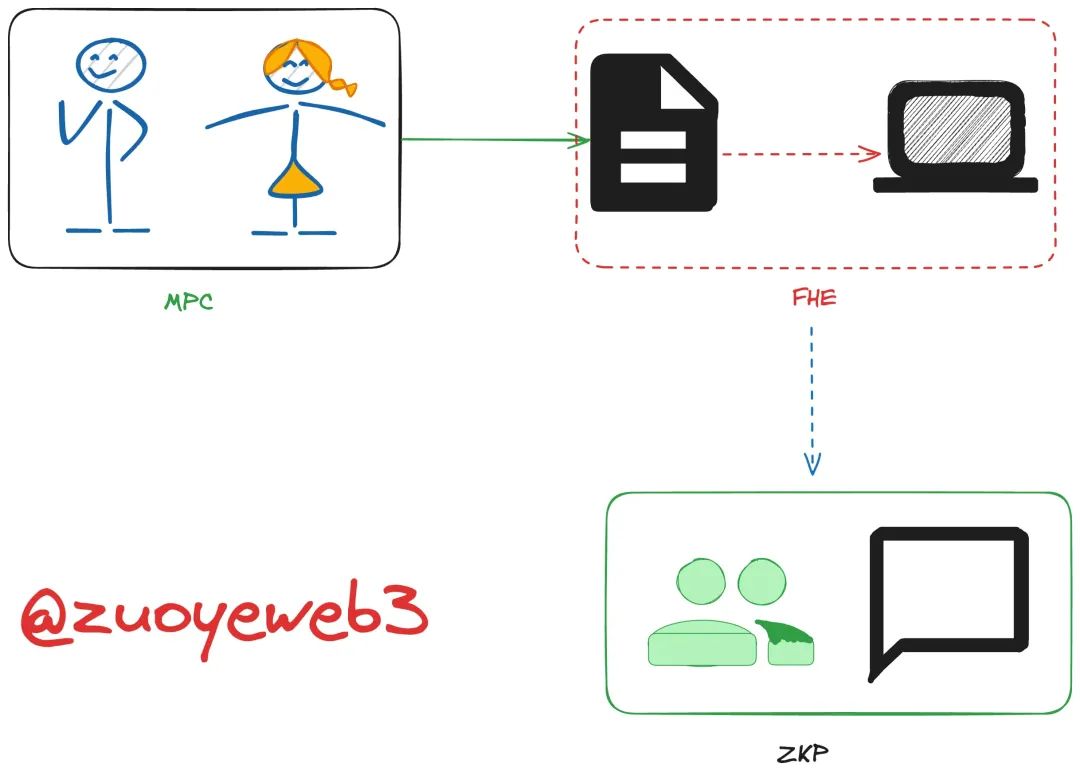

In this article, I aim to outline a history of cryptographic technology distinct from typical narratives about shifts within the crypto industry—such as the relationships between FHE, ZK, and MPC. From a high-level application perspective, MPC initiates the process, FHE enables intermediate computations, and ZK provides final verification. In terms of adoption timeline, ZK was first implemented, followed by the surge in popularity of Account Abstraction (AA) wallets, which elevated MPC as a key technical approach with accelerating development. FHE, meanwhile, was prophetically heralded around 2020 but only began gaining traction in 2024.

MPC/FHE/ZKP

Unlike ZK and MPC—and indeed unlike all existing encryption methods—FHE does not merely attempt to build an "unbreakable cipher system" for absolute security. Instead, FHE aims to make encrypted ciphertexts functional. Encryption and decryption are important, but data should not be wasted between encryption and decryption.

Theory Complete, Web2 Leads Web3 in Adoption

FHE is a foundational technology whose theoretical foundations have already been established in academia. Major Web2 players—including Microsoft, Intel, IBM, and Duality supported by DARPA—have invested heavily in hardware-software integration and development tooling.

Here's some good news: even these Web2 giants aren't sure how to best use FHE yet, so Web3 isn’t too late to enter the field. But there’s bad news too: Web3 compatibility is nearly nonexistent. Mainstream chains like Bitcoin and Ethereum cannot natively support FHE algorithms. Although Ethereum bills itself as the “world computer,” performing FHE computations directly might take until the end of the world.

We’ll focus primarily on Web3 explorations, but it’s essential to remember that Web2 giants are deeply committed to FHE and have laid substantial groundwork.

This emphasis stems from Vitalik’s focus on ZK from 2020 to 2024.

Let me briefly explain why ZK became so popular: after Ethereum adopted Rollups as its scaling strategy, ZK’s state compression capabilities drastically reduced the volume of data transmitted from L2 to L1—offering significant economic value. Of course, this is still largely theoretical. New challenges such as L2 fragmentation, sequencer centralization, and excessive fee extraction by certain L2/Rollup operators remain unresolved issues requiring further innovation.

To summarize: Ethereum needed scalability, chose the Layer 2 path, and saw ZK-Rollups and OP-Rollups compete fiercely, leading to a broad industry consensus favoring OP short-term and ZK long-term—giving rise to the quartet of ARB, OP, zkSync, and StarkNet.

Economic efficiency was—and arguably remains—the sole reason ZK gained acceptance in the crypto world, especially within the Ethereum ecosystem. Therefore, rather than delve into FHE’s technical features, we should focus on where FHE can improve Web3 operational efficiency or reduce costs. Any compelling use case must deliver either cost savings or performance gains.

A Brief History and Achievements of FHE

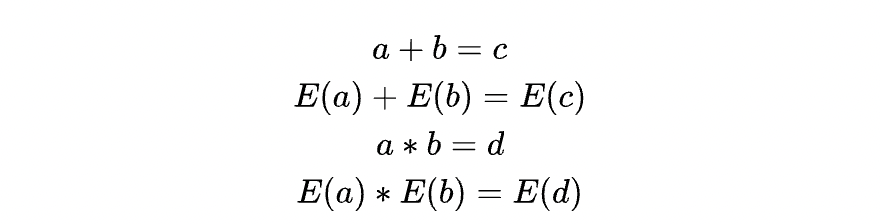

First, let's distinguish homomorphic encryption from fully homomorphic encryption (FHE). Strictly speaking, FHE is a special case of homomorphic encryption. Homomorphic encryption means that “performing addition or multiplication on ciphertext yields the same result as performing those operations on plaintext,” i.e.:

Here, c and E(c), d and E(d) can be considered equivalent. However, two major challenges exist:

-

Plaintext-ciphertext equivalence involves adding noise to plaintext before encryption. If accumulated noise becomes too large during computation, results become invalid. Thus, controlling noise growth via specialized algorithms is critical.

-

Ciphertext operations incur enormous computational overhead—often 10,000 to 1 million times slower than plaintext operations. Only schemes supporting unlimited additions and multiplications qualify as fully homomorphic. Nonetheless, partially homomorphic systems offer unique value depending on their capabilities:

-

Partially Homomorphic Encryption (PHE): supports only limited operations (e.g., addition OR multiplication).

-

Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption (SHE): allows a limited number of both additions and multiplications.

-

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE): supports arbitrary numbers of additions and multiplications, enabling general-purpose computation on encrypted data.

The journey of FHE began in 2009 when Craig Gentry proposed the first FHE scheme based on ideal lattices—a mathematical structure defining point sets in multidimensional space satisfying specific linear relations.

In Gentry’s design, ideal lattices represent keys and encrypted data, allowing private computations while maintaining confidentiality. A technique called bootstrapping reduces noise accumulation—metaphorically akin to “lifting oneself by one’s bootstraps.” Practically, this involves re-encrypting ciphertexts to refresh them, preserving secrecy while enabling complex computations.

(Bootstrapping is crucial for FHE practicality, though deeper mathematics won’t be explored here.)

Gentry’s breakthrough proved FHE’s feasibility in engineering terms, but the computational cost was prohibitive—each operation could take thirty minutes. Practical deployment seemed impossible.

Once the “zero-to-one” challenge was overcome, progress shifted toward scalable implementation—designing new algorithms based on different mathematical assumptions. Beyond ideal lattices, Learning With Errors (LWE) and its variants emerged as dominant security foundations.

In 2012, Zvika Brakerski, Craig Gentry, and Vinod Vaikuntanathan introduced the BGV scheme—one of the second-generation FHE frameworks. Its key contribution was modulus switching, effectively managing ciphertext noise growth and enabling Leveled FHE: systems capable of executing homomorphic computations up to a predefined circuit depth.

Other notable schemes include BFV and CKKS. CKKS notably supports floating-point arithmetic, albeit at higher computational cost—highlighting the need for continued optimization.

Later came TFHE and FHEW, particularly TFHE—the preferred algorithm of Zama. In essence, while bootstrapping (first used by Gentry) mitigates noise, TFHE achieves efficient bootstrapping with strong precision guarantees, making it well-suited for blockchain applications.

We won’t compare these schemes in detail; differences are less about superiority and more about suitability for specific contexts. All require robust software and hardware support. Even TFHE demands co-design with hardware for mass adoption—unlike ZK, which followed an “algorithm-first, hardware-later” path. In crypto, FHE must evolve alongside hardware from day one.

Web2 OpenFHE vs Web3 Zama

As noted earlier, Web2 giants have made tangible progress in FHE, yielding practical tools applicable to Web3 scenarios.

To simplify: IBM developed the Helib library (supporting BGV and CKKS); Microsoft’s SEAL supports CKKS and BFV—with Song Yongsoo, one of CKKS’ creators, contributing to SEAL. OpenFHE, developed by Duality (backed by DARPA), integrates BGV, BFV, CKKS, TFHE, and FHEW, likely making it the most comprehensive FHE library available today.

OpenFHE has experimented with Intel’s CPU acceleration libraries and NVIDIA’s CUDA interface for GPU acceleration. However, CUDA’s last known FHE-related update dates back to 2018. Please correct me if newer developments exist.

OpenFHE supports C++ and Python, with Rust APIs under development. It emphasizes modular, cross-platform usability—making it the easiest choice for Web2 developers seeking plug-and-play FHE capabilities.

For Web3 developers, however, things get harder.

Most public blockchains lack the computational power to execute FHE algorithms. Moreover, ecosystems like Bitcoin and Ethereum currently lack economic incentives for FHE adoption. Recall: ZK gained traction because of a real need—efficient data transmission from L2 to L1. You can’t force FHE adoption just because you have the technology; that’s hammering screws. Such forced fits only increase deployment costs.

FHE + EVM Working Principle

Below, I’ll explore current challenges and potential use cases—but first, a word of encouragement for Web3 builders.

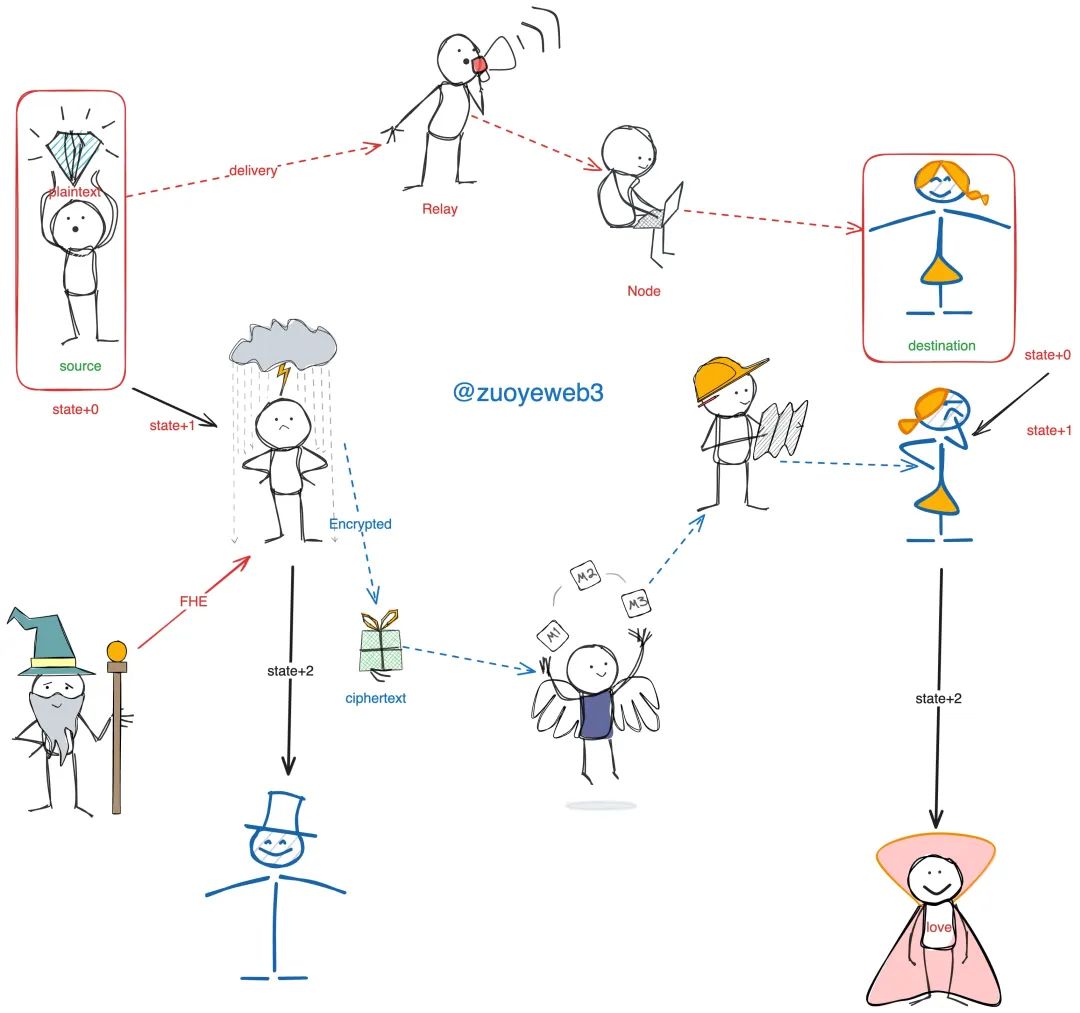

In 2024, Zama secured the largest FHE-focused funding round in crypto history: $73 million led by Multicoin. Zama offers the TFHE algorithm library and fhEVM—a framework for building FHE-enabled EVM-compatible chains.

Performance issues must be addressed through software-hardware collaboration. The EVM cannot natively run FHE contracts, but this doesn’t conflict with Zama’s approach—they’re building their own chain with native FHE support. Creating new chains with FHE capability isn’t hard—Shiba Inu plans a Layer 3 using Zama’s tech. The real challenge lies in enabling native FHE contract deployment on Ethereum itself, requiring EVM opcode support. Good news: Fair Math and OpenFHE co-hosted the FHERMA competition, inviting developers to modify EVM opcodes—an active step toward integration.

Hardware acceleration is equally vital. Even high-performance chains like Solana would grind to a halt if they natively supported FHE. Native FHE hardware includes Chain Reaction’s 3PU™ (Privacy Protection Processing Unit), an ASIC solution. Zama and Inco also explore acceleration—Zama currently achieves ~5 TPS, Inco reaches 10 TPS. Inco believes FPGA-based acceleration could boost throughput to 100–1,000 TPS.

Still, speed concerns shouldn’t dominate discussions. Existing ZK hardware acceleration techniques could likely be adapted for FHE. Hence, our focus below will center on identifying viable use cases and solving EVM compatibility—not premature optimization.

Dark Pools Fade, FHE x Crypto Future Shines

When Multicoin led Zama’s round, they boldly declared: “ZKP is past; FHE is future.” Whether that prophecy comes true remains uncertain. After Zama, networks like Inco and Fhenix formed an invisible fhEVM alliance—diverging slightly in focus but united in vision: integrating FHE with the EVM ecosystem.

Timing matters. Let’s start with a splash of cold water.

2024 may be FHE’s breakout year, but Elusiv—a Solana-based “dark pool” launched in 2022—has shut down. Its codebase and documentation have been deleted.

Ultimately, FHE functions as part of a broader toolkit alongside MPC and ZKP. We must ask: where can FHE fundamentally change blockchain paradigms?

Let’s admit it: the belief that FHE enhances privacy and thus holds economic value is flawed. Historical evidence shows Web3 users don’t prioritize privacy unless it brings tangible benefits. Hackers use Tornado Cash to hide stolen funds; ordinary users stick to Uniswap because privacy tools add time and cost.

The computational burden of FHE further strains already-limited on-chain resources. Privacy only scales when the added cost delivers disproportionate returns—as seen in RWA bond issuance. For instance, in June 2023, Bank of China International issued a blockchain-based structured note via UBS to Asia-Pacific clients. UBS announced it was done on Ethereum, yet no contract or distribution address appears on-chain. If anyone finds it, please share.

This case illustrates FHE’s relevance: institutional clients want public chains but don’t wish to disclose everything. Here, FHE’s ability to display ciphertexts while enabling direct trading makes it superior to ZKP.

For retail users, FHE remains distant infrastructure. Possible directions include MEV resistance, private transactions, secure networking, and anti-surveillance—but none are primary needs. Using FHE today slows networks. Frankly, FHE’s moment hasn’t arrived.

Privacy is often a nice-to-have, not a must-pay-for public good. To drive adoption, we need use cases where FHE’s computable ciphertexts cut costs or boost efficiency—creating organic market demand. Many MEV-resistant solutions exist; centralized sequencers alone can mitigate much of it. FHE doesn’t directly solve core pain points.

Another issue is computational inefficiency. Superficially, this seems like a solvable engineering problem via hardware or algorithmic improvements. But fundamentally, it reflects weak market demand. Without strong incentives, teams lack motivation to optimize. Efficiency gains come from competition. Look at ZK: booming demand fueled fierce rivalry between SNARK and STARK, with Rollups competing furiously on languages and compatibility—driving rapid advancement under capital pressure.

Use cases and real-world deployment are FHE’s gateway to becoming blockchain infrastructure. Without crossing this threshold, FHE will remain a fringe experiment—projects tinkering in isolation without broader impact.

From the practice of Zama and friends, a consensus emerges: build new chains outside Ethereum, reuse ERC-20 and other standards, and create FHE L1/L2 bridges. This approach allows early experimentation and component development. The downside? If Ethereum itself never supports FHE, off-chain solutions will always occupy a marginalized position.

Zama recognizes this. Beyond its libraries, it founded FHE.org and sponsors conferences to accelerate academic-to-engineering translation.

Inco Network envisions a “universal privacy computing layer”—essentially a compute outsourcing model. Built on Zama’s TFHE, it operates an FHE-EVM L1. An intriguing experiment partners with cross-chain messaging protocol Hyperlane: games running on another EVM chain can offload FHE-intensive logic to Inco via Hyperlane, returning only results to the source chain.

For this vision to work, EVM chains must trust Inco’s integrity, and Inco must deliver sufficient throughput. Delivering low-latency, high-concurrency performance in gaming environments poses significant challenges.

Extending this idea, certain zkVMs could also serve as FHE compute providers. RISC Zero, for example, already has this capability. The next collision between ZK products and FHE may spark unexpected innovations.

Further still, some projects seek closer alignment with Ethereum—ideally becoming part of it. If Inco builds an FHE L1 using Zama, Fhenix aims to build an FHE L2. Still evolving, it’s unclear what product will emerge—perhaps an L2 specializing in FHE functionality.

Additionally, consider the aforementioned FHERMA competition—developers skilled in Ethereum can participate, advance FHE adoption, and earn rewards.

Then there’s Sunscreen and Mind Network—two unusual projects. Sunscreen, primarily run by Ravital, focuses on building a BFV-based compiler tailored for FHE. It remains in testing, far from production readiness.

Finally, Mind Network explores combining FHE with existing use cases like restaking—though implementation details remain unproven.

One last note: Elusiv rebranded as Arcium, raised new funding, and pivoted to “parallel FHE”—aiming to improve execution efficiency.

Conclusion

This article appears to discuss FHE theory and practice, but its underlying thread traces the evolution of cryptographic technology itself—a narrative distinct from mere crypto-application technologies. ZKP and FHE share similarities, both aiming to preserve privacy without sacrificing blockchain transparency. Yet ZKP succeeded by reducing L2<>L1 interaction costs, whereas FHE still searches for its killer app.

Classification of Approaches

The road ahead is long. FHE continues its quest. We can classify current efforts by proximity to Ethereum:

-

Type 1: Independent Kingdom, Bridging Ethereum. Represented by Zama, Fhenix, and Inco Network—focused on foundational tooling, encouraging independent FHE L1/L2 development for niche applications;

-

Type 2: External Add-on, Integrating with Ethereum. Led by Fair Math and Mind Network—retaining some independence while pursuing deeper Ethereum integration.

-

Type 3: Co-evolution, Transforming Ethereum. If Ethereum cannot natively support FHE, exploration must shift to the contract layer, spreading FHE functionality across EVM-compatible chains. No clear project fits this mold yet.

Unlike ZK—which saw tooling and hardware mature only late in its lifecycle—FHE stands on the shoulders of ZK’s giants. Launching an FHE chain today may be easy, but bridging it meaningfully to Ethereum is the hardest part.

Daily self-reflection in the blockchain world to find FHE’s future:

-

Which scenarios absolutely require encryption instead of plaintext?

-

Which scenarios specifically require FHE over other encryption methods?

-

Which scenarios leave users satisfied enough with FHE to pay premium fees?

To be continued—I’ll keep watching FHE!

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News