Vitalik: Does using ZK technology for digital identity eliminate risks?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik: Does using ZK technology for digital identity eliminate risks?

Zero-knowledge proof wrapping (ZK-wrapping) solves many important problems.

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: Saoirse, Foresight News

Today, the use of zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) in digital identity systems to protect privacy has become somewhat mainstream. Various ZK passport projects—referring to digital identity initiatives based on zero-knowledge proof technology—are developing highly user-friendly software packages that allow users to prove they hold valid credentials without revealing any details about their identity. World ID (formerly Worldcoin), which uses biometric verification combined with zero-knowledge proofs for privacy protection, recently surpassed 10 million users. A government digital identity project in Taiwan, China has adopted zero-knowledge proofs, and the European Union’s work in digital identity is also placing increasing emphasis on ZKP-based solutions.

At first glance, the widespread adoption of zero-knowledge-proof-based digital identities might seem like a major victory for d/acc—a concept proposed by Vitalik in 2023 advocating decentralized technological advancement through tools such as cryptography and blockchain, aiming to balance innovation with security, privacy, and human autonomy while accelerating progress and defending against risks. Such systems could protect our social media platforms, voting systems, and various internet services from Sybil attacks and bot manipulation without sacrificing privacy. But is it really this simple? Do ZKP-based identities still carry risks? This article will clarify the following points:

-

ZK-wrapping solves many important problems.

-

ZK-wrapped identities still carry risks. These risks appear less tied to whether the underlying credential is biometric or passport-based; most issues—such as privacy leaks, vulnerability to coercion, and system errors—stem primarily from the rigid enforcement of the “one person, one identity” property.

-

The opposite extreme—using “proof of wealth” to counter Sybil attacks—is insufficient for most applications, so we need some form of identity-like solution.

-

The theoretical ideal lies between these two extremes: the cost of obtaining N identities should scale quadratically as N².

-

This ideal state is difficult to achieve in practice, but pluralistic identity comes close and thus represents the most realistic solution. Pluralistic identity can be explicit (e.g., social-graph-based identity) or implicit (multiple types of ZK identities coexisting, with no single type approaching 100% market share).

How Do ZK-Wrapped Identities Work?

Imagine you obtain a World ID by scanning your eye, or a ZK-passport-based identity by using your phone’s NFC reader to scan a passport. For the purposes of this discussion, both methods share core properties (with only minor edge differences, such as cases involving dual citizenship).

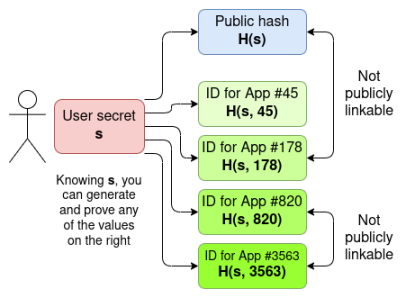

On your phone, there exists a secret value s. On a public chain-based global registry, there is a corresponding public hash H(s). When logging into an application, you generate an app-specific user ID: H(s, app_name), and use a zero-knowledge proof to verify that this ID originates from the same secret s associated with one of the public hashes on the registry. Thus, each public hash can generate only one ID per application, but it never reveals which app-specific ID corresponds to which public hash.

In practice, designs may be more complex. In World ID, the app-specific ID is actually a hash incorporating both the app ID and session ID, allowing disassociation of different actions within the same app. Similar constructions can be applied to ZK-passport designs.

Before discussing the drawbacks of this identity model, it's essential to recognize its advantages. Outside niche circles of zero-knowledge identity (ZKID), proving yourself to identity-requiring services often requires disclosing your full legal identity. This severely violates the computer security principle of least privilege: a process should receive only the minimum permissions and information necessary to complete its task. These services need only verify that you are not a bot, are over 18, or come from a specific country—but instead, they gain access to pointers to your entire identity.

The current best alternative involves indirect tokens like phone numbers or credit card details: here, the entity knowing your phone/credit card number linked to in-app activity is separate from the one linking that number to your legal identity (a telecom company or bank). But this separation is fragile—phone numbers and similar data can easily leak.

ZK-wrapping—a technique leveraging zero-knowledge proofs to protect user identity privacy, enabling users to prove identity without exposing sensitive data—resolves much of this problem. However, the next point is less commonly discussed: some issues remain unaddressed, and may even worsen due to the strict "one person, one identity" constraint inherent in these systems.

Zero-Knowledge Proofs Alone Do Not Enable Anonymity

Suppose a ZK-identity platform operates exactly as intended, fully implementing all the logic described above, and has even found ways to help non-technical users securely preserve their private data long-term without relying on centralized institutions. Still, consider a realistic assumption: applications themselves won’t actively cooperate with privacy goals. They’ll follow a “pragmatic” approach, adopting designs promoted under the banner of “maximizing user convenience,” but which often align with their own political and commercial interests.

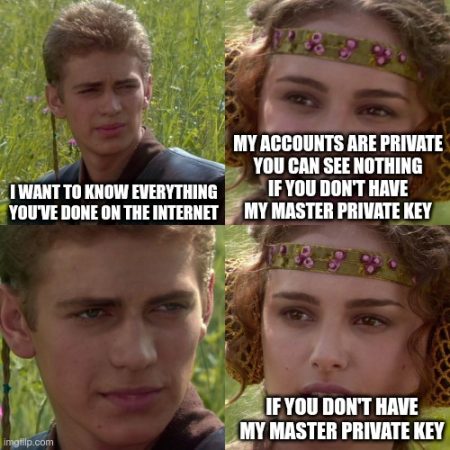

In this scenario, social media apps won’t adopt complex mechanisms like frequent session key rotation. Instead, they’ll assign each user a unique app-specific ID. And because the identity system enforces “one person, one identity,” users can have only one account (in contrast to today’s “weak IDs,” like Google accounts, where individuals easily create around five). In reality, anonymity typically requires multiple accounts—one for a “main identity,” others for various anonymous personas (see finsta and rinsta). Therefore, under this model, the actual level of anonymity users can achieve may fall below current levels. As a result, even ZK-wrapped “one-person-one-identity” systems could push us toward a world where all activities must attach to a single public identity. In an era of rising risks (e.g., drone surveillance), removing people’s choice to protect themselves via anonymity would have serious negative consequences.

Zero-Knowledge Proofs Alone Cannot Protect Against Coercion

Even if you keep your secret value s private and no one sees public linkages across your accounts, what happens if someone forces you to disclose it? Governments might mandate disclosure of the secret value to review all associated activities. This isn’t hypothetical: the U.S. government already requires visa applicants to disclose their social media accounts. Employers could easily make full disclosure a condition of employment. Individual apps might technically require users to reveal their identities on other platforms before allowing registration (which “sign in with app” defaults enable).

Again, in these situations, the benefits of zero-knowledge proofs vanish, yet the downsides of the new “one-account-per-person” feature persist.

We might reduce coercion risks through design improvements—for example, using multi-party computation to generate each app-specific ID, requiring both user and service provider participation. Without the app operator’s involvement, users couldn't prove ownership of their app-specific ID. This increases the difficulty of forcing someone to reveal their full identity, though it doesn’t eliminate the possibility. Moreover, such schemes introduce other drawbacks—for instance, requiring app developers to act as real-time active entities rather than passive on-chain smart contracts (which require no ongoing intervention).

Zero-Knowledge Proofs Alone Cannot Address Non-Privacy Risks

All forms of identity face edge cases:

-

Government-rooted IDs, including passports, fail to cover stateless individuals and those who haven’t yet obtained official documents.

-

Conversely, such government-based identity systems grant unique privileges to individuals with multiple nationalities.

-

Passport-issuing authorities may suffer hacks, and hostile foreign intelligence agencies might forge millions of fake identities (e.g., if Russian-style “guerrilla elections” spread, false identities could manipulate election outcomes).

-

Biometric identities completely fail for individuals whose relevant biological features are damaged due to injury or illness.

-

Biometric identities are vulnerable to spoofing. If biometric identity becomes valuable enough, we might see organized cultivation of human organs solely to “mass-produce” such identities.

These edge cases are most damaging in systems enforcing the “one person, one identity” rule—and they have nothing to do with privacy. Hence, zero-knowledge proofs offer no remedy.

Proof of Wealth Is Insufficient to Prevent Sybil Attacks, So We Need Some Form of Identity System

Within pure cypherpunk circles, a common alternative is to rely entirely on “proof of wealth” to prevent Sybil attacks, avoiding any form of identity system altogether. By imposing a cost per account, mass creation becomes economically unfeasible. There are precedents online—for example, Somethingawful forums required a $10 one-time fee to register, with no refund upon ban. However, in practice, this isn’t truly cryptographic-economic, since the main barrier to creating a new account isn’t re-paying $10, but acquiring a new credit card.

Theoretically, payments could be conditional: upon registration, you stake funds, losing them only in rare cases like account bans. This could dramatically raise attack costs in theory.

This scheme works well in many contexts, but fails completely in certain scenarios. I’ll focus on two categories: “UBI-like” and “governance-like” applications.

Demand for Identity in UBI-Like Scenarios

“UBI-like” scenarios refer to contexts where assets or services must be distributed widely (ideally universally) to users regardless of payment ability. Worldcoin exemplifies this systematically: anyone with a World ID receives small periodic amounts of WLD tokens. Many token airdrops pursue similar informal goals, attempting to place at least some tokens into as many hands as possible.

Personally, I don’t believe such tokens will reach levels sufficient to sustain livelihoods. In an AI-driven economy with wealth magnitudes thousands of times greater than today, such tokens might support basic living; even then, government-led programs backed by natural resource wealth would likely dominate economically. Nevertheless, I think these “mini-UBIs” can realistically solve one critical issue: giving people enough cryptocurrency to perform basic on-chain transactions and online purchases, such as:

-

Obtaining ENS names

-

Publishing a hash on-chain to initialize a zero-knowledge identity

-

Paying fees on social media platforms

If cryptocurrency achieves global adoption, this problem disappears. But until then, this may be the only way for people to access on-chain non-financial applications and related online goods and services—otherwise, they might remain entirely excluded.

Another way to achieve similar results is “universal basic services”: granting every verified identity holder limited free transaction rights within specific applications. This approach may better align incentives and improve capital efficiency, as each benefiting application funds access only for its users, not non-users. However, trade-offs exist—lower universality (users are guaranteed access only to participating apps). Still, even here, an identity solution is needed to prevent spam attacks and avoid exclusivity stemming from requiring payment methods not universally accessible.

A final important category is “universal basic security deposit.” One function of identity is providing an accountability anchor without requiring users to stake capital proportional to incentive size. This helps lower participation barriers based on personal capital—even eliminating capital requirements altogether.

Demand for Identity in Governance-Like Scenarios

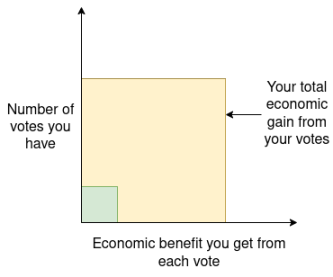

Consider a voting system (e.g., likes and retweets on social media): if User A has ten times the resources of User B, A gets ten times the voting power. Economically, each unit of voting power yields A ten times the benefit it gives B (because A’s larger scale means decisions impact them more significantly). Overall, A gains 100 times more benefit from their vote than B does from theirs. Consequently, A invests far more effort in voting, studying optimal strategies, and potentially manipulating algorithms. This explains why whales wield disproportionate influence in token-based voting systems.

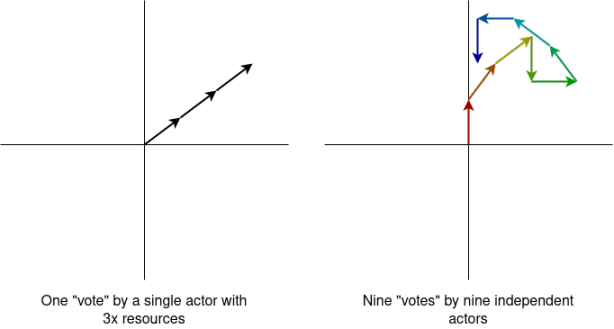

A deeper, more general reason: governance systems shouldn’t treat “one person holding $100,000” the same as “1,000 people jointly holding $100,000.” The latter represents 1,000 independent individuals, containing richer, non-redundant information. Signals from 1,000 people also tend to be “milder,” as differing opinions cancel out.

This applies not only to formal voting systems but also to “informal voting,” such as public discourse shaping cultural evolution.

This suggests governance systems won’t truly accept treating equally sized financial bundles identically regardless of origin. Systems need to understand the internal coordination level behind each bundle.

Note: if you agree with my framing of these two scenarios (UBI-like and governance-like), then technically speaking, the need for a strict “one person, one vote” rule disappears.

-

For UBI-like applications, what’s needed is an identity scheme where the first identity is free, and obtainable identity count is bounded—not rigidly fixed, but costly enough that attacking the system becomes meaningless.

-

For governance-like applications, the core need is an indirect metric to judge whether a given resource bundle stems from a single controlling entity or a “naturally formed,” loosely coordinated group.

In both cases, identity remains useful—but the requirement to strictly enforce “one person, one identity” dissolves.

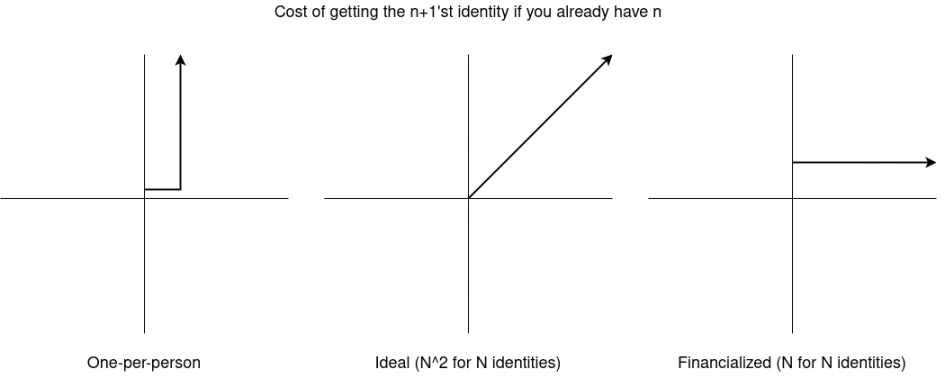

The Theoretical Ideal: Cost of N Identities Scales as N²

From the above arguments, two opposing pressures constrain how hard it should be to acquire multiple identities:

First, we must not impose a clear, hard cap on the number of easily obtainable identities. If one can have only one identity, anonymity vanishes and coercion risk rises. Even a fixed number greater than one poses danger: if everyone knows each person has five identities, you might be coerced into revealing all five.

Another supporting argument: anonymity itself is fragile, so we need ample safety margin. Modern AI tools make cross-platform user behavior linkage trivial—word choice, posting time, intervals, topics—all publicly available signals totaling just 33 bits can precisely identify a person. People might defend with AI tools (e.g., writing anonymously in French, then using a locally run LLM to translate into English), but even then, no one wants a single mistake to permanently end their anonymity.

Second, identity cannot be fully tied to finances (i.e., cost scaling linearly as N), as this allows large actors disproportionate influence (leaving small actors voiceless). Twitter Blue illustrates this: an $8 monthly verification fee is too low to meaningfully deter abuse, and users now largely ignore the badge.

Beyond that, we probably don’t want an actor with N times the resources to freely commit N times the harmful actions.

Combining these arguments, we want multiple identities to be obtainable as easily as possible while satisfying two constraints: (1) limiting large actors’ power in governance applications; (2) curbing abuse in UBI-like applications.

Directly borrowing the mathematical model from earlier governance discussions yields a clear answer: if having N identities confers N² influence, then acquiring N identities should cost N². Coincidentally, this same principle applies neatly to UBI-like applications.

Longtime readers of this blog may notice this matches exactly the chart from an earlier post on “quadratic funding”—and that’s no accident.

Pluralistic Identity Achieves This Ideal

“Pluralistic identity” refers to identity mechanisms without a single dominant issuer—be it individual, organization, or platform. This can be achieved in two ways:

-

Explicit pluralistic identity (also known as “social-graph-based identity”). You prove your identity (or other claims, e.g., membership in a community) via attestations from others in your network, whose identities are in turn validated by the same mechanism. The paper “Decentralized Society” elaborates on such designs, and Circles is a live implementation.

-

Implicit pluralistic identity. This reflects the current status quo: numerous identity providers coexist—including Google, Twitter, local equivalents in various countries, and various government-issued IDs. Few apps accept only one authentication method; most support multiple, simply to reach potential users.

Latest snapshot of the Circles identity graph. Circles is among the largest running social-graph-based identity projects.

Explicit pluralistic identity naturally supports anonymity: you can have one (or multiple) anonymous identities, each building reputation through actions within communities. An ideal explicit pluralistic system might not even require discrete identities; instead, you’d possess a fuzzy set of verifiable past behaviors, selectively proving different subsets as needed.

Zero-knowledge proofs will make anonymity easier: you could bootstrap an anonymous identity from your main identity by privately providing an initial signal (e.g., proving via ZKP possession of a certain amount of tokens to post on anon.world; or proving via ZKP that your Twitter followers meet certain criteria). There may be even more effective uses of ZKPs.

Implicit pluralistic identity has a cost curve steeper than linear but flatter than quadratic—yet retains most desired properties. Most people possess some, but not all, of the identity forms listed here. You can exert effort to acquire another, but the more you have, the lower the marginal return on acquiring the next. Thus, it provides necessary resistance against governance attacks and other abuses, while ensuring coercers cannot demand—or reasonably expect—you to disclose any fixed set of identities.

Any form of pluralistic identity—explicit or implicit—is inherently more fault-tolerant: someone with hand or eye disabilities may still hold a passport; stateless individuals may still prove identity through non-governmental channels.

Crucially, if any single identity form approaches 100% market share and becomes the sole login option, these beneficial properties collapse. In my view, this is the greatest risk facing overly “universal” identity systems: once near-total dominance is achieved, they shift the world from pluralistic identity back to “one person, one identity”—a model with numerous documented flaws.

In my opinion, the ideal outcome for current “one person, one identity” projects is integration with social-graph-based identity systems. The biggest challenge for social-graph-based projects is scaling to massive user bases. “One person, one identity” systems could provide initial scaffolding—creating millions of “seed users”—reaching a scale sufficient to safely grow a global, distributed social graph from that foundation.

Special thanks to Balvi volunteers, Silviculture members, and World team members for discussions.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News