Introducing ERC-7683: A New Cross-Chain Intent Standard Jointly Developed by Uniswap and Across

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Introducing ERC-7683: A New Cross-Chain Intent Standard Jointly Developed by Uniswap and Across

ERC7683 aims to optimize user experience for solutions and lower the barrier to entry into the universal solution network.

Author:Nick Pai, Archetype

Translation: TechFlow

This article is divided into two parts. First, I explain why I believe chain abstraction infrastructure is critical for consumer adoption of crypto, and why intent-based architecture is the best way to design it. Second, I describe the main barrier to widespread adoption of intents: solver network activity.

At the end of this article, I propose a solution and introduce a standard developed through collaboration between Across and Uniswap, based on feedback from the CAKE Working Group. This standard aims to optimize solver user experience, lower the barrier to entry into a universal solver network, enable routing of most intents through this network, and ultimately allow larger, more competitive solver networks to thrive.

Agenda

Problem:

-

Defining the end state: What makes a crypto application "usable"?

-

Why is "chain abstraction" the solution to the user experience problems created by the fundamental topology of modular blockchains?

-

Why must usable crypto applications be built atop chain abstraction infrastructure?

Solution Space:

-

How intent-based architectures produce chain abstraction

-

Understanding that intent markets perform best when the solver network is large and competitive

-

Bootstrapping intent solver networks requires introducing more applications that generate intents

Proposal:

-

Why we need a cross-chain intent standard prioritizing "solver user experience" to scale solvers and intent markets to a size sufficient for network effects

Usable crypto applications cannot be built without chain abstraction

Are our best and brightest building redundant infrastructure?

Many complain that top crypto engineers are overly focused on providing more blockspace to end users. This criticism has merit; there are far too many L2 solutions available to end users relative to demand.

However, I reject the view that no useful crypto applications exist.

Decentralized finance empowers individuals with self-custody of digital assets, allowing them to bypass restrictive service providers and use their digital assets to purchase things of real-world value. The promise of self-custody of data also offers a utopian alternative for those increasingly concerned about trusting FAANG monopolies to safeguard their data.

I believe the real issue is not a lack of useful crypto applications, but friction experienced by end users trying to access them. End users should experience the following when interacting with crypto applications:

-

Speed: Applications should feel as fast as web2 apps

-

Cost: Unlike web2, all web3 interactions must incur some cost, but the "per-click" cost should be negligible

-

Censorship resistance ("permissionless"): Anyone with a wallet should be able to interact with an app as long as they can afford fees

-

Security: Clicks should do exactly what users expect, cannot be reversed, and all web3 updates should be permanent

These are the attributes of a "usable" crypto application.

We've been trying to build usable crypto for a long time

Today's modular blockchain solutions provide consumers with all these attributes—but not all in the same place.

In 2020, blockchains were monolithic, offering end users two out of three attributes: speed, cost, or security. Then we envisioned a rollup-centric or modular future capable of unlocking all three simultaneously.

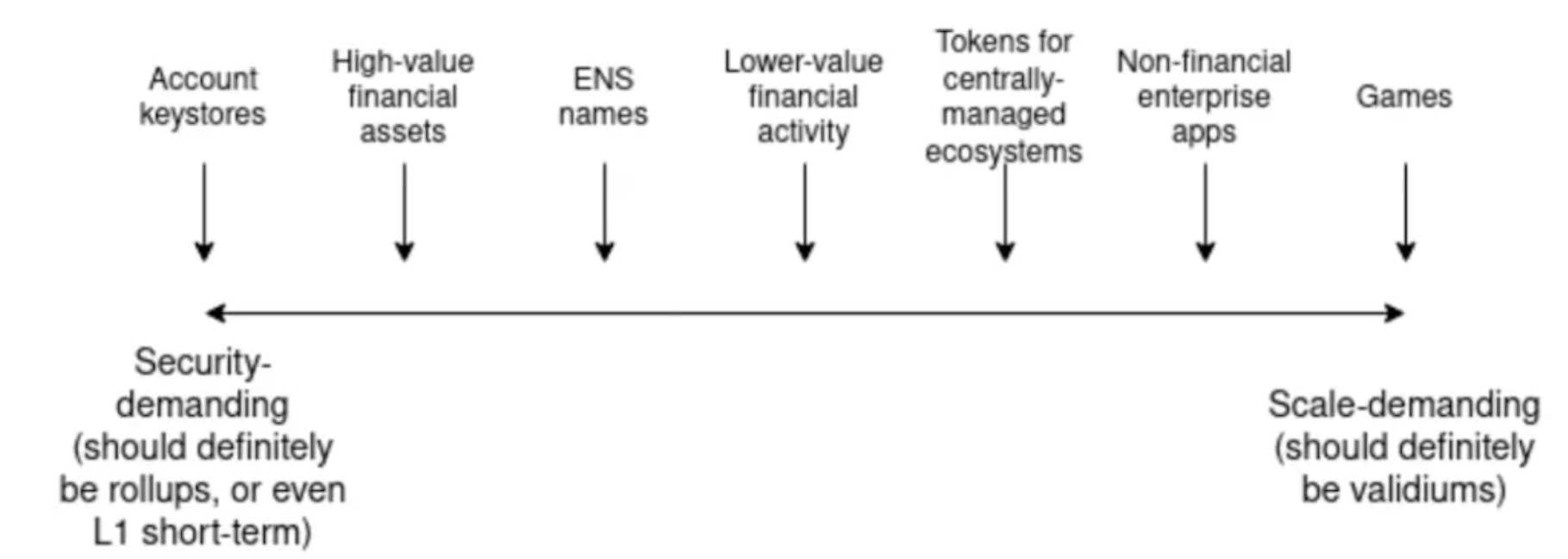

Today, we’ve laid the foundation for such rollup-centric infrastructure. L2s offer cheap and fast blockspace, and most L2s provide permissionless blockspace. In contrast, L1 provides censorship-resistant (WW3-proof) secure blockspace (read more about the tradeoffs between security provided by L1/L2 and user experience in my article). These L2s are securely connected to L1 via standardized message paths, laying the groundwork for a modular and interoperable network. Over the past four years, we've built the fiber optics connecting blockchains that support useful crypto applications. But why are modular blockchains still so unusable?

The inevitability of modular blockchain networks is that capital assets will cluster on the most secure layers, while user clicks will cluster on faster and cheaper layers.

Modular blockchain topology encourages secure blockspace to be offered on different layers than cheap and fast blockspace. Users naturally prefer to store their value on the most secure networks, yet demand frequent interaction with cheaper and faster networks. By design, canonical paths between L2 and L1 are slow and/or expensive. These phenomena explain why users must traverse these canonical paths—using L1 assets to pay for L2 interactions—leading to "unusable" crypto experiences.

The goal of chain abstraction is to reduce friction when users send value across these protocol paths. Chain abstractors assume users prefer specifying their desired end state to dapps as an "intent," leaving dapps responsible for fulfilling it. Users shouldn't have to compromise custody of secure assets just to access low fees and latency.

Thus, chain abstraction means enabling users to transfer value across networks securely, cheaply, and quickly. A common user flow today involves a user holding USDC on a "secure" chain like Ethereum wanting to mint an NFT or swap a new token on a new chain like Blast or Base. The fewest-step approach is sequentially executing bridge → swap → mint transactions (or swap → bridge → mint).

In this example, the user’s intent is to use their USDC on the secure chain to mint an NFT on another chain. As long as they receive the NFT and their USDC balance is deducted from their chosen custodial location, the user is satisfied.

Intent-based architecture is the only path to building chain abstraction

Chain abstraction relies on cross-chain value transfer, but sending value via canonical message paths is either expensive or slow. "Fast bridges" offer users cheap and fast alternatives for sending value across networks but introduce new trust assumptions. Message passing is the most intuitive method for building fast bridges because it's modeled after TCP/IP; it relies on a bridge protocol acting as a TCP router connecting two chains.

ResearchGate's TCP/IP diagram

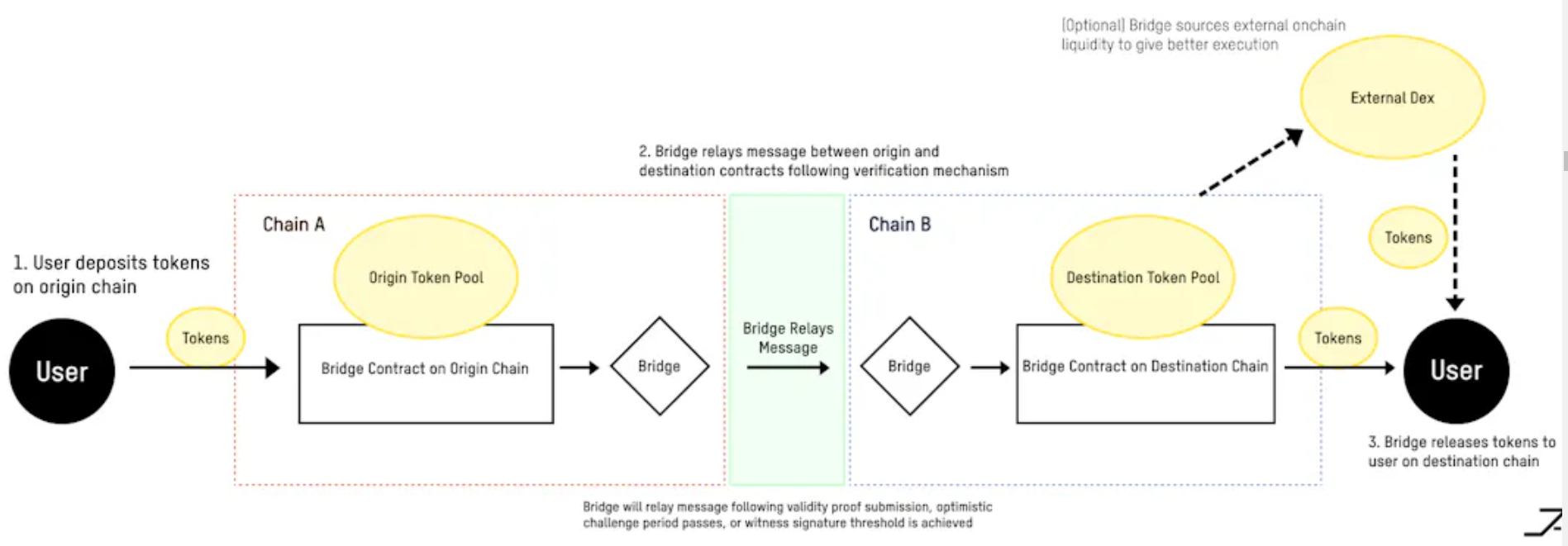

Value transfer via message passing involves the bridge protocol sending messages between contracts on the source and destination chains. This message is triggered by a user transaction on the source side and relayed to the destination side once its "validity" is verified.

Messages can only be validated after the initiating transaction on the source chain has finalized—that is, permanently included in the canonical blockchain of the source chain. Validation can occur via validity proofs showing inclusion in the source chain's consensus, optimistic proposals, or after accumulating a certain number of witness signatures on the source side. Once relayed to the bridge contract on the destination chain, tokens are released to the user.

This architecture has several fundamental issues:

-

The validation mechanism must wait for full finality before relaying the message to the destination chain's contract. For L2s with optimistic finality periods, this could take up to seven days.

-

Each bridge transaction sends only one cross-chain message, or batches messages together—but the entire batch can only be sent after the last message in the batch completes.

-

Bridges have limited ability to access external liquidity to offer users better pricing because they must declare the fulfillment path of the user’s intent.

Message-passing fast bridges will inevitably be insecure, slow, or expensive depending on the validation mechanism. Intent markets offer an alternative fast bridge architecture rooted in a key insight:

Value is fungible—recipients don’t care how value is transferred as long as they receive it

Can bridges outsource value transfer to a sophisticated agent to improve speed and reduce costs? Liquidity is dynamic on and off-chain; if bridge mechanisms can flexibly choose optimal execution paths during transfers, price improvements become possible.

Intent mechanisms allow users to specify precise conditions or covenants under which their value transfer transactions may execute.

The simplest intent is an order to pay X tokens on chain A to receive Y tokens on chain B.

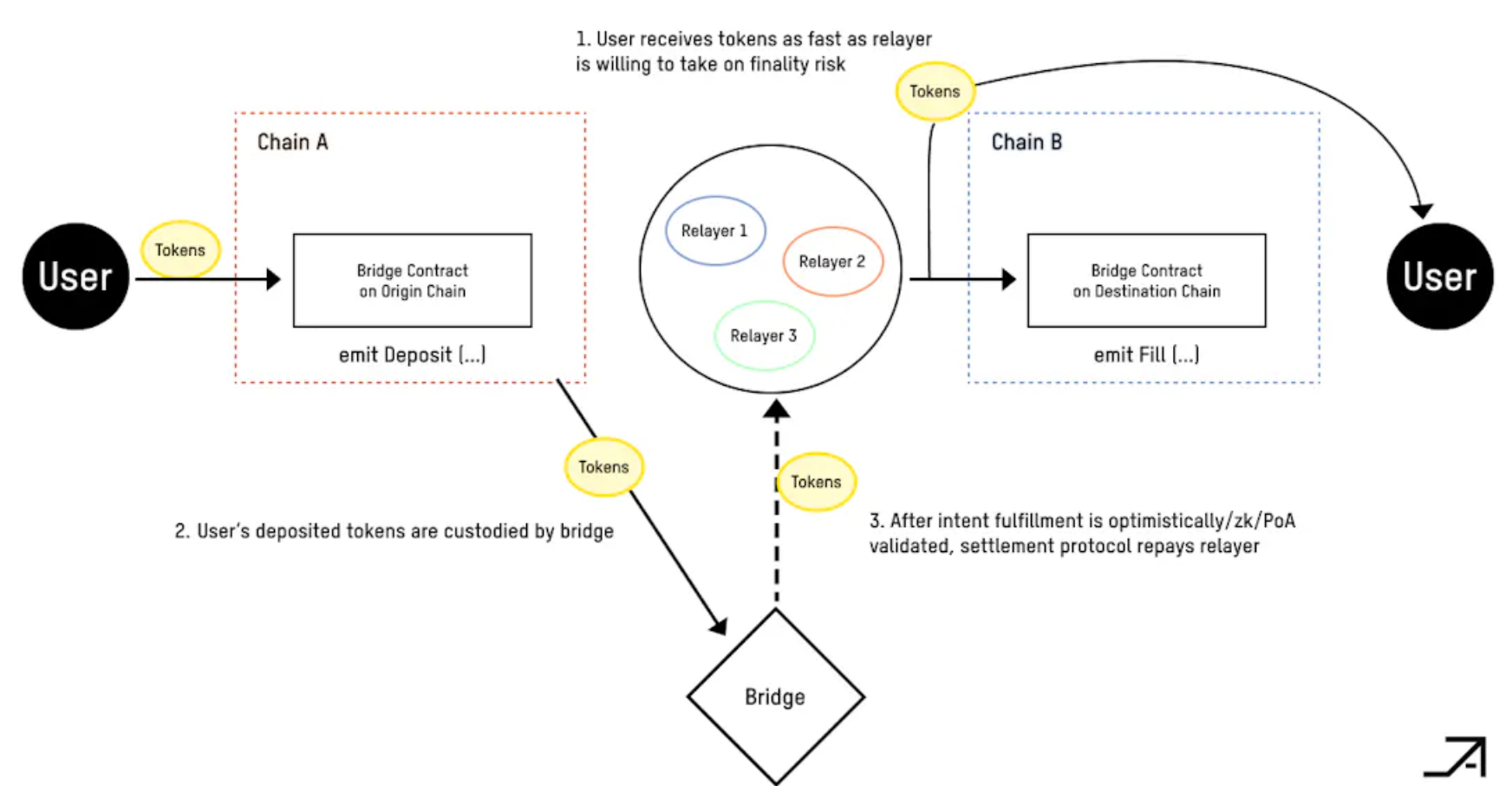

Bridge protocols don’t need to send messages between domains to satisfy users’ cross-domain intents. Instead, protocols outsource value transfer to agents selected from a permissionless solver network, with individual solvers later seeking reimbursement from the bridge protocol. In contrast, message-passing mechanisms precisely specify how their transactions should execute and don’t rely on agent availability.

Intent Settlement Protocols

Intent-based bridge protocols can be more precisely labeled as intent settlement protocols, responsible for ensuring solvers don’t violate user-specified conditions. Intent settlement protocols provide solvers guarantees that they’ll be reimbursed and rewarded upon fulfilling user intents. To do so, intent settlement protocols may appeal to Oracles to verify authenticity of intent fulfillment. Oracle security can be based on optimistic challenge periods, witness thresholds, or ZK validity proofs.

Because individual solvers can assume finality risk and determine optimal execution paths, intent settlement protocols enable fast, low-cost value transfer

Message-passing bridges can only communicate once the source chain achieves finality. Today, finality takes seven days on optimistic rollups and one hour on ZK rollups. While finality times should decrease with wider adoption of ZK light clients and advances in shared sequencer pre-confirmations, finality will likely never feel "instantaneous" to users across all blockchains—indicating ongoing demand for fast bridge solutions. Without assuming finality risk, even bridges adding a trusted intermediary to guarantee losses from chain reorgs cannot accelerate message passing beyond finality windows.

The acceleration offered by intent-based architectures arises because individual solvers within heterogeneous solver networks can assume more finality risk than message-passing protocols and fulfill user intents before chain reorg risks fully dissipate. Solvers then charge users a premium for assuming this finality risk in exchange for faster execution.

Outsourcing cross-chain intent fulfillment to agents also improves average user pricing. In intent-based bridging, front-running solvers who fulfill orders on the destination chain are later reimbursed by the system. These intent settlements can be batched together to amortize costs. Unlike users, fillers don’t require immediate reimbursement and will charge users accordingly for capital upfront. Batching isn’t unique to intent-based architectures, but it synergizes well because the architecture separates reimbursement from intent fulfillment steps.

Greater price improvements come from the intuition that value is fungible—timely discovery of optimal paths often beats direct value transfer—though some paths remain unbeatable on cost, such as transmitting USDC over CCTP.

Message-passing bridges must encode how they'll transmit value to users. Some send tokens from liquidity pools at predetermined exchange rates, while others mint representative tokens for recipients who must later swap them for canonical token assets.

When fulfilling user intents, agents can aggregate liquidity from both on-chain and off-chain venues. Competitive solver networks theoretically offer users infinite liquidity sources (though even these may rapidly deplete during one-sided trends in high-volatility events like popular NFT mints, airdrops, or rug pulls).

After submitting cross-chain orders as intents, solvers can internalize MEV generated by the order as price improvement.

Intent-based architectures are fundamentally designed to be secure

Intent-based bridges can be securely built because they separate users' urgent needs from the complex requirements of settlement networks. Solvers can wait for reimbursement—unlike users—and will charge users based on how long the settlement protocol makes them wait. Thus, intent settlements can use very robust verification mechanisms without strict time constraints. From a security perspective, this is preferable because verifying intent fulfillment is intuitively complex.

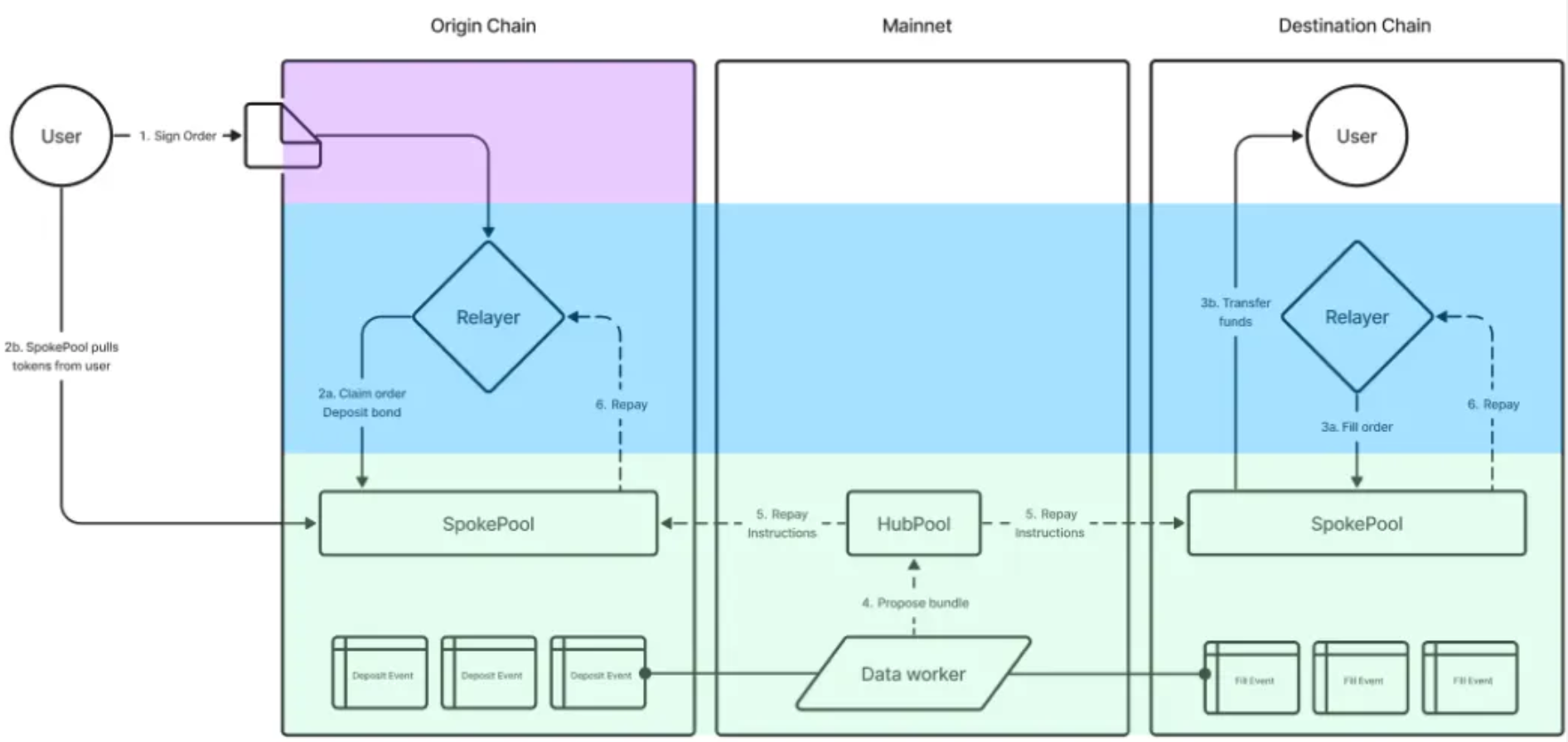

As an example of intent verification in production, Across batch-verifies and reimburses fillers after a 90-minute optimistic challenge period. Of course, settlement networks should strive to reimburse fillers as quickly as possible to reduce end-user fees. An improvement over optimistic challenges would be a ZK validity proof mechanism, requiring encoding intent verification logic into a ZK circuit. In my view, it's inevitable that verification proof mechanisms will replace optimistic challenges, enabling intent settlement networks to reimburse users faster.

So how does chain abstraction emerge from intent-based architecture?

Recall that chain abstraction requires fast and cheap cross-chain value transfer. It also shouldn’t require users to submit on-chain transactions on the network where they store their assets.

If Permit2 or EIP-3074 signatures are included, user intents don’t need to be submitted on-chain by the user. This holds true for both message-passing and intent-based bridges. Both architectures can leverage the Permit2 pattern, allowing users to offline sign the amount of tokens they’re willing to spend from their source chain wallet.

Intent-based markets best support chain abstraction because they enable cheap and fast cross-chain value transfer. Imagine a user requesting a solver to quote converting their USDC on Optimism into a WETH collateral position on Arbitrum. The user could send this intent to an RFQ auction, where solvers bid. The winning solver receives the user’s signed intent containing authorization to spend their USDC on Optimism, the amount of WETH to receive on Arbitrum, and calldata for depositing this WETH into an Arbitrum collateral position. The solver then submits this transaction (on behalf of the user) on Optimism to initiate the cross-chain intent and withdraw USDC from the user’s Optimism wallet. Finally, the solver fulfills the intent by sending WETH to the user and forwarding the calldata to open the user’s collateral position on Arbitrum.

Building chain abstraction infrastructure means making user flows feel instant and cheap without requiring on-chain transactions. Let’s conclude this article by discussing barriers to broader intent adoption.

To achieve optimal user experience from intent-based chain abstraction, we need a competitive solver network

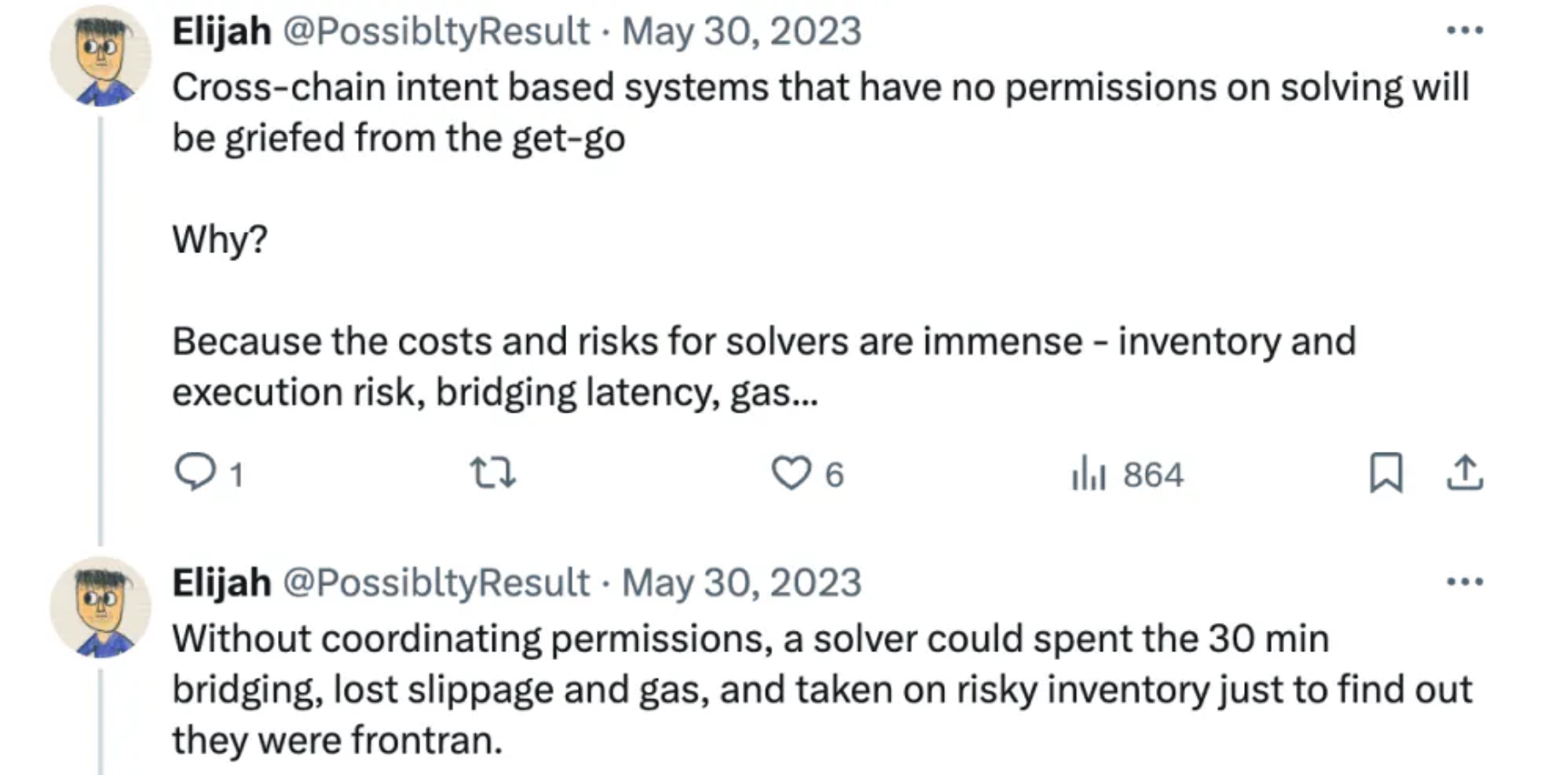

The key to achieving optimal UX from intent-based chain abstraction lies in building a competitive solver network. Bridges connecting intents depend on solver network effects to outperform message-passing variants. This is the core tradeoff between intent and message-passing architectures. The reality is not every intent-generating application needs access to a fully competitive set of solvers—some may prefer routing intents to oligopolistic solver networks. However, the current state of solver networks is immature and far from meeting the level of solver network activity assumed by intent markets.

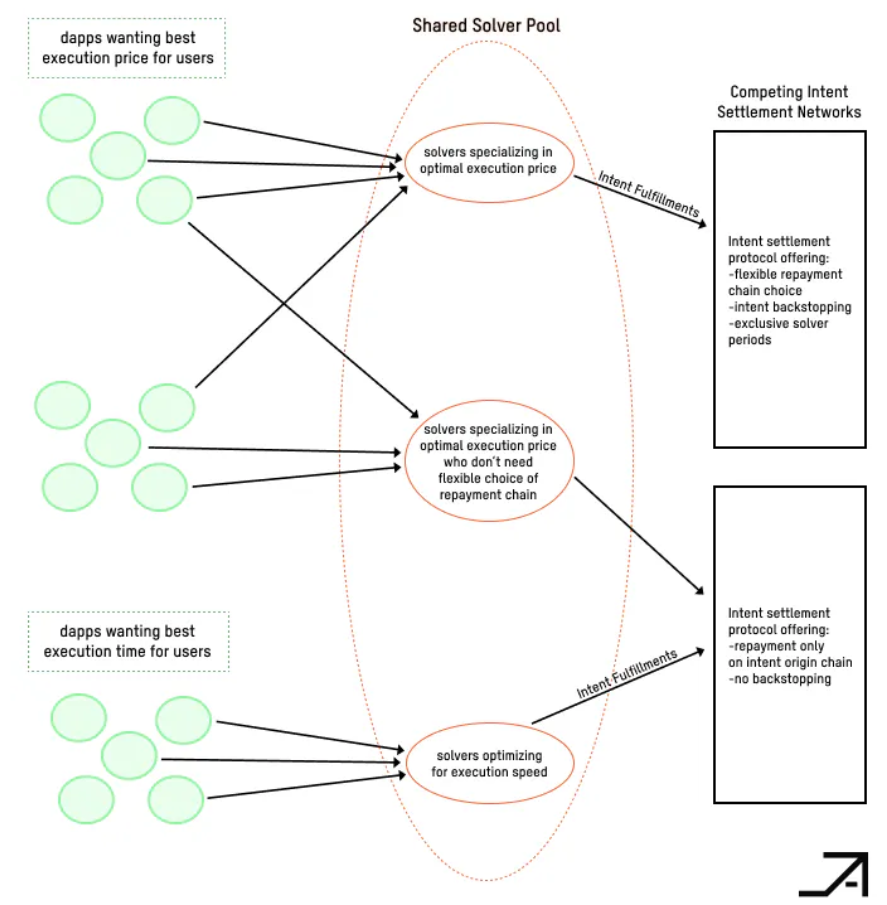

We don’t want every DApp routing intents to isolated solver networks. The optimal UX scenario is many DApps communicating with the same pool of solvers, with all DApps free to change which solver pool they send intents to.

How do we bootstrap solver networks?

We must prioritize solver user experience above all else.

Running intent solvers is complex, requiring expertise in building high-performance software and managing cross-chain inventory risk. Naturally, few parties will be interested in paying the setup costs. Ideally, a solver written for one DApp—like the UniswapX solver—could be reused to solve other intent-generating DApps like Across and CowSwap.

We truly need to increase total capital efficiency across all intent-based DApps’ solver networks. This will require addressing barriers to running solvers.

To achieve this, we need intent-generating DApps to be visible to any solver, and ensure all solvers can access multiple differentiated and competitive intent settlement networks. This will give solvers confidence they can route their intent fulfillment to settlement networks they trust. Competition among settlement networks will also lower solver costs.

The value proposition of intent settlement networks is providing solvers with security and potentially other features influencing their decision to fill intents.

A solver’s choice of intent settlement network will affect their ability to offer users fee and execution time guarantees. Some settlement networks might offer solver-exclusive periods, supporting off-chain auctions where solvers and users negotiate and commit relay fees. (Additionally, these intent auctions might offer economically secured pre-confirmations, further enhancing UX. For insights into user flows involving auctions and pre-confirmations, I recommend Karthik from Sorella’s talk.)

Some settlement networks may offer intent expiration (sending value back to users after a fulfillment deadline), intent backing (settlement networks use their own balance sheets to fulfill user intents if no solver does), or flexible repayment chains (allowing solvers to choose their preferred chain for reimbursement).

Ultimately, settlement networks will fiercely compete to reimburse solvers quickly and cheaply without compromising security. In turn, solvers will route their order flow to settlement networks allowing them to offer the cheapest fees to win DApp order flow. Competition between settlement and solver networks depends on all parties in the intent supply chain coordinating around a common language—competition will lead to optimal UX for cross-chain value transfer.

Clearly, we need a cross-chain intent standard

If solvers can assume intents will share common elements, they can reuse code to solve intents initiated by different DApps, reducing setup costs. If different DApps create intents conforming to the same standard, they can route all intents to the same solver pool. This will help onboard next-generation DApps by letting them plug their cross-chain intents directly into existing mature solver pools without needing separate integrations—gaining access to cheap, fast, secure, and permissionless value transfer.

Third-party tracking software will also find it easier to track intent status for any new DApp if standards are followed.

This intent standard should allow intent originators or solvers to specify which settlement network they want to settle their intent on.

I envision competing settlement protocols (like SUAVE, Across, Anoma, and Khalani) offering solvers different features. Depending on which settlement network is reimbursing solvers, solvers can offer different price and time guarantees to intent owners. DApps and solvers can agree to route user intents to settlement networks they trust to avoid censorship, maintain data privacy, and ensure sufficient security for solvers to trust reimbursement.

By writing the choice of settlement network into the intent order itself, solvers can incorporate this certainty into the quotes they show users. Solvers and users can eliminate upfront uncertainty in bridge pricing before submitting intents on-chain, thereby reducing costs.

In collaboration with Uniswap and based on CAKE Working Group feedback, Across and I propose the following cross-chain intent standard, prioritizing solver user experience

This standard aims to simplify work for solvers. One opinionated choice it makes is natively supporting Permit2/EIP3074 with nonce and initiateDeadline, providing fillers with certain guarantees such as the refund amount they’ll receive from the settlement network and a predictable user intent format they can track. Additionally, the standard defines an initiation function allowing fillers (those bringing orders on-chain) to specify extra "fillerData" on-chain that the user didn’t know at the time of signing CrossChainOrder. This ensures fillers are rewarded by the settlement contract for submitting the user’s meta-transaction and allows them to set repayment-specific information like the repayment chain.

This standard also aims to make it easier for DApps to track intent completion status. Any settlement contract implementing this standard should create a custom subtype ResolvedCrossChainOrder, parsable from an arbitrary orderData field. This might include tokens involved in swaps, destination chains, and other fulfillment constraints. The standard includes a resolve function enabling DApps to understand how to display intent status to users and helping solvers know the exact intent order structure they’re handling.

The design goal of this standard is to enhance solver user experience, making it easier for them to support multiple settlement networks and deterministically calculate their rewards. I believe this will enable them to offer users more accurate and tighter quotes. You can read more details about this standard, named ERC7683, in this post and the discussion on the Ethereum Magicians forum.

Conclusion

"Intents" are confusing because they aren’t defined—and this lack of definition is causing real UX deficiencies.

Everyone wants others to adopt their definition of intents, so I fully acknowledge that establishing a standard in practice is nearly impossible. I believe the right approach to industry standards is first defining intent settlement systems, then attracting order flow.

In my view, a more feasible path is for prominent DApps already generating significant user traffic and many intents to agree on conforming to some minimum standard, which their existing solvers will adopt. This will form a new, larger solver pool. By aggregating order flow from already prominent venues, this new solver pool will earn higher profits and offer better prices to end users. Eventually, new DApps will also demand routing their intents to this solver pool and supporting its intent standard.

To kickstart this process, Across and Uniswap have jointly proposed a standard for all participants in the intent supply chain to use when handling user orders to send X tokens from chain A and receive Y tokens on chain B. Order flow run through UniswapX (with comparative advantages in auction design and intent origination) and Across (with comparative advantages in settling intent fulfillment) can merge, initiating the cultivation of a larger, more competitive solver network.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News