Merlin Technical Solution Explained: How Does It Actually Work?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Merlin Technical Solution Explained: How Does It Actually Work?

Help more people understand Merlin's general workflow and gain a clearer understanding of its security model.

Author: Faust, Geeker Web3

Since the summer of inscriptions in 2023, Bitcoin Layer2 has remained a central focus of the entire Web3 space. Although this sector emerged significantly later than Ethereum Layer2, Bitcoin's unique appeal through POW and the successful launch of spot ETFs—free from concerns over "securitization" risks—has drawn billions of dollars in capital attention to the Layer2 derivative赛道 within just half a year.

Within the Bitcoin Layer2 landscape, Merlin, with tens of billions of dollars in TVL, is undoubtedly the largest and most watched project. Thanks to clear staking incentives and attractive yields, Merlin rose rapidly within months, creating an ecosystem myth that surpasses even Blast. As Merlin gains increasing popularity, discussions around its technical architecture have also attracted growing interest.

In this article, Geeker Web3 focuses on the technical design of Merlin Chain, interpreting its publicly available documentation and protocol design philosophy. Our goal is to help more people understand Merlin’s general workflow and gain clearer insights into its security model, offering an intuitive understanding of how this “top-tier Bitcoin Layer2” actually operates.

Merlin’s Decentralized Oracle Network: An Open Off-Chain DAC Committee

For all Layer2 solutions—whether Ethereum-based or Bitcoin-based—data availability (DA) and data publication costs are among the most critical challenges. Given Bitcoin’s inherent limitations and lack of support for high data throughput, efficiently utilizing this scarce DA space has become a key test of creativity for Layer2 teams.

One conclusion is obvious: if a Layer2 directly publishes raw transaction data onto Bitcoin blocks, neither high throughput nor low fees can be achieved. The mainstream solutions involve either highly compressing the data before uploading it to Bitcoin blocks, or publishing the data entirely off-chain.

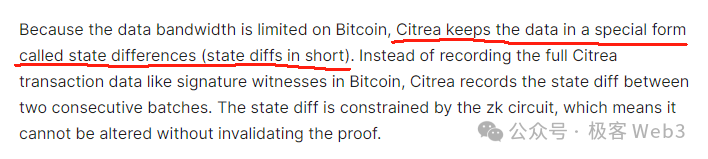

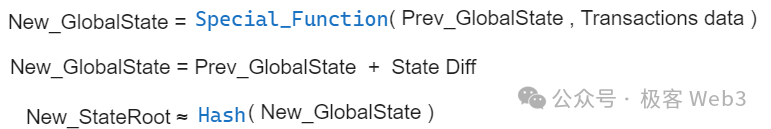

Among Layer2 projects following the first approach, Citrea stands out. It plans to upload the state differences (state diff)—i.e., changes across multiple accounts over a period—alongside corresponding ZK proofs, directly onto the Bitcoin blockchain. This allows anyone to download the state diff and ZKP from the Bitcoin mainnet and monitor Citrea’s state transitions. This method reduces on-chain data size by over 90%.

While this greatly reduces data size, the bottleneck remains apparent. If numerous accounts undergo state changes simultaneously, the Layer2 must aggregate and upload all these changes to Bitcoin, resulting in high data publication costs—a limitation evident in many Ethereum ZK Rollups.

Many Bitcoin Layer2s take the second path: using off-chain DA solutions, either by building their own DA layer or leveraging platforms like Celestia or EigenDA. B^Square, BitLayer, and Merlin—the subject of this article—all adopt such off-chain DA scaling approaches.

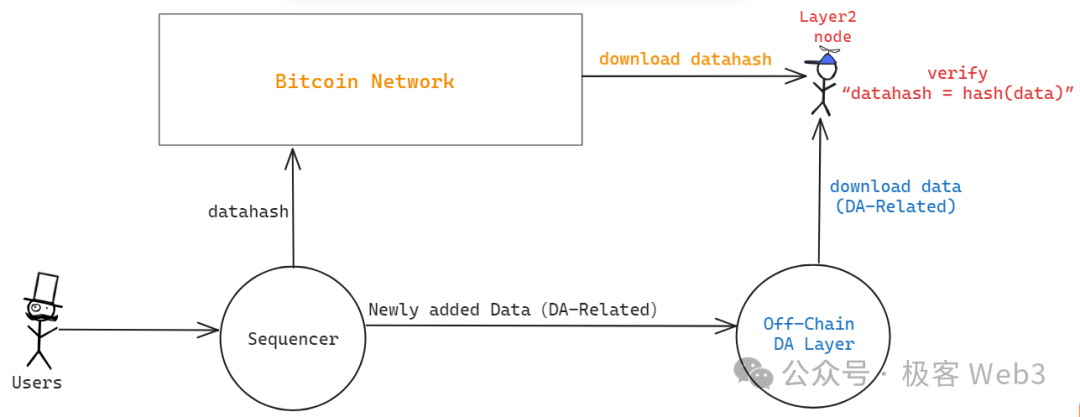

As discussed in our previous article—“Analyzing B^2’s Updated Technical Roadmap: The Necessity of Off-Chain DA and Verification Layer on Bitcoin”—B^2 directly mimics Celestia by constructing an off-chain DA network called B^2 Hub, supporting data sampling. DA data such as transaction data or state diffs are stored off-chain, while only the datahash/merkle root is submitted to the Bitcoin mainnet.

This essentially uses Bitcoin as a trustless bulletin board: anyone can read the datahash from the Bitcoin chain. After obtaining DA data from off-chain providers, users can verify whether it matches the on-chain datahash—i.e., hash(data1) == datahash1?. If they match, the off-chain provider has delivered accurate data.

(Architecture diagram of Layer2 with DA layer below Bitcoin, source: Geeker Web3)

This process ensures that data provided by off-chain nodes corresponds to certain “clues” on Layer1, preventing malicious DA layers from submitting fake data. However, there is a crucial attack vector: what if the data source—the Sequencer—never actually disseminates the full data corresponding to the datahash, and instead only submits the datahash to Bitcoin while deliberately withholding the actual data from public access?

Similar scenarios include publishing only the ZK proof and StateRoot without releasing the underlying DA data (state diff or transaction data). While users can verify the ZK proof and confirm the validity of the transition from Prev_StateRoot to New_StateRoot, they cannot know which accounts’ states have changed. In such cases, although user assets remain secure, no one can determine the actual network state—what transactions were included, which contracts updated—and the Layer2 effectively halts.

This is known as “data withholding.” Dankrad from the Ethereum Foundation briefly discussed similar issues on Twitter in August 2023, focusing particularly on something called a “DAC.”

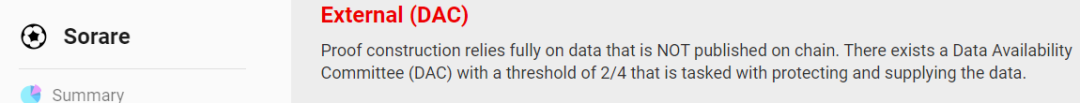

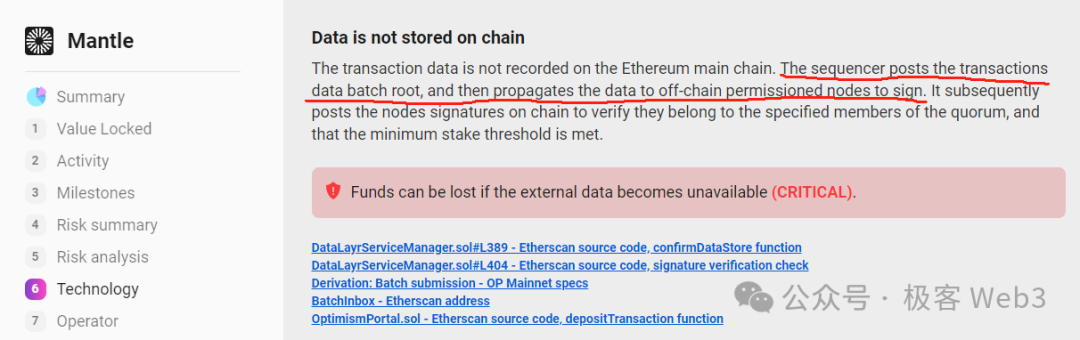

Many Ethereum Layer2s using off-chain DA set up a committee of specially privileged nodes called a Data Availability Committee (DAC). This DAC acts as a guarantor, attesting that the Sequencer has indeed published complete DA data (transaction data or state diff) off-chain. The DAC nodes then collectively generate a multisig signature; once the threshold is met (e.g., 2 out of 4), the Layer1 contract assumes the Sequencer has passed DAC verification and properly published the full DA data off-chain.

Ethereum Layer2 DAC committees mostly follow a POA model, allowing only a few KYC-verified or officially designated nodes to join, making DAC synonymous with “centralization” and “consortium chains.” Moreover, in some DAC-based Ethereum Layer2s, the Sequencer sends DA data exclusively to DAC member nodes, requiring permission from the DAC for any external access—functionally equivalent to a consortium chain.

Clearly, DACs should be decentralized. While Layer2 doesn’t need to publish DA data directly on Layer1, DAC membership must be open to prevent collusion among a small group. (For further discussion on DAC attack vectors, refer to Dankrad’s prior tweets.)

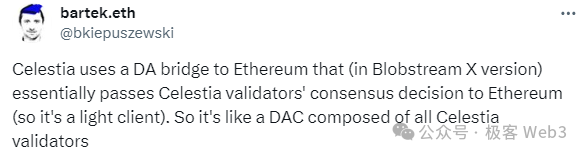

Celestia’s proposed BlobStream essentially replaces centralized DACs with Celestia itself: Ethereum L2 sequencers publish DA data to the Celestia chain, and if 2/3 of Celestia validators sign it, the dedicated Layer2 contract on Ethereum recognizes the DA data as properly published. Here, Celestia validators act as guarantors. With hundreds of validators, this large-scale DAC is considered relatively decentralized.

Merlin’s DA solution closely resembles Celestia’s BlobStream, both adopting a POS model to open DAC participation and promote decentralization. Anyone who stakes sufficient assets can run a DAC node. In Merlin’s documentation, these DAC nodes are referred to as Oracles, and the system supports staking not only BTC and MERL but also BRC-20 tokens, enabling flexible staking mechanisms including proxy staking similar to Lido. (The POS staking protocol for Oracles is one of Merlin’s core narratives going forward, offering relatively high staking yields.)

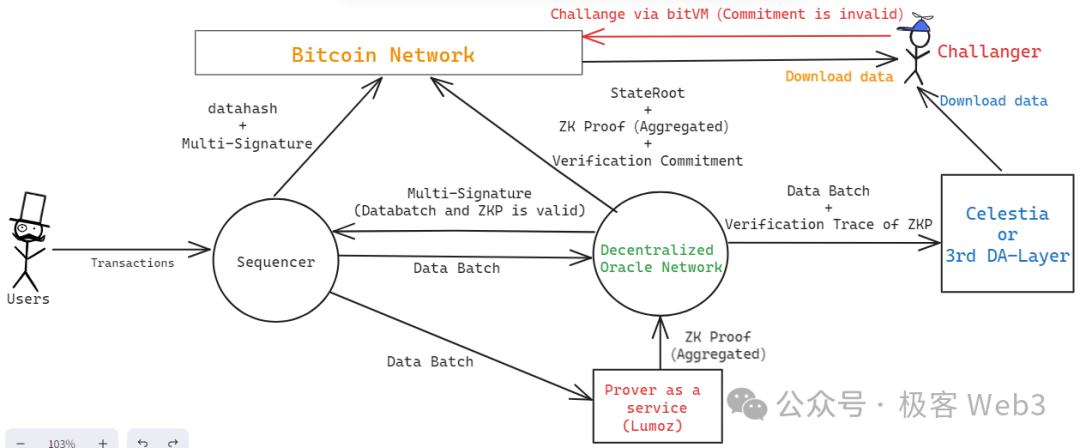

Here’s a brief overview of Merlin’s workflow (illustrated below):

- After receiving numerous transaction requests, the Sequencer aggregates them into a data batch and sends it to both Prover nodes and Oracle nodes (decentralized DAC).

- Merlin’s Prover nodes are decentralized, utilizing Lumoz’s Prover-as-a-Service. Upon receiving multiple data batches, the Prover pool generates corresponding zero-knowledge proofs, which are then sent to Oracle nodes for verification.

- Oracle nodes verify whether the ZK proofs from Lumoz’s Prover pool correctly correspond to the data batches from the Sequencer. If matched and error-free, validation passes. During this process, decentralized Oracle nodes use threshold signatures to generate a multisig, publicly attesting that the Sequencer has fully released the DA data and that the corresponding ZKP is valid and verified.

- The Sequencer collects the multisig result from Oracle nodes; once the signature count meets the threshold, it posts the signature information to the Bitcoin chain along with the datahash of the DA data (data batch), enabling external parties to retrieve and verify it.

(Merlin architecture diagram, source: Geeker Web3)

- Oracle nodes perform special computations during ZK proof verification to generate a Commitment, which is posted to the Bitcoin chain, allowing anyone to challenge it. This process mirrors bitVM’s fraud proof protocol. If a challenge succeeds, the Oracle node that posted the Commitment faces economic penalties. Additionally, data published by Oracles to Bitcoin includes the current Layer2 state hash (StateRoot) and the ZKP itself, both made available for external validation.

Reference: “Simplified Explanation of BitVM: How Fraud Proofs Are Verified on BTC Chain”

A few additional details: Merlin’s roadmap mentions that Oracles will eventually back up DA data to Celestia, allowing Oracle nodes to prune local historical data rather than storing it permanently. Also, the Commitment generated by the Oracle Network is actually the root of a Merkle Tree. Simply disclosing the root isn't enough—the full dataset behind the Commitment must be made public, necessitating a third-party DA platform, which could be Celestia, EigenDA, or another DA layer.

Security Model Analysis: Optimistic ZK-Rollup + Cobo’s MPC Service

Above, we outlined Merlin’s operational flow, giving readers a basic grasp of its structure. It’s clear that Merlin, like B^Square, BitLayer, and Citrea, follows a shared security model—an “Optimistic ZK-Rollup.”

At first glance, this term may seem odd to Ethereum enthusiasts. What exactly is an “optimistic ZK-Rollup”? In the Ethereum community, the theoretical model of ZK Rollups relies entirely on cryptographic computation reliability, requiring no trust assumptions. The word “optimistic,” however, introduces a trust assumption—meaning users must generally assume the Rollup operates correctly unless proven otherwise. Only when errors occur can challengers submit fraud proofs to penalize operators. This is the origin of “Optimistic Rollup,” or OP Rollup.

To Ethereum’s Rollup-centric ecosystem, an optimistic ZK-Rollup may seem incongruent. Yet it precisely fits the reality of Bitcoin Layer2. Due to technical constraints, Bitcoin cannot fully verify ZK proofs on-chain. Instead, it can only validate specific steps under exceptional circumstances. Thus, Bitcoin currently only supports fraud proof protocols—allowing users to identify computational errors in off-chain ZKP verification and challenge them via fraud proofs. While not as robust as Ethereum-style ZK Rollups, this represents the most reliable and secure model currently achievable for Bitcoin Layer2.

Under this optimistic ZK-Rollup framework, assuming there are N entities capable of initiating challenges within the Layer2 network, the state transition remains secure as long as at least one of these challengers is honest and able to detect and report errors via fraud proofs. However, a mature optimistic rollup must also protect its withdrawal bridge with fraud proofs. Currently, nearly all Bitcoin Layer2s fail to meet this requirement and instead rely on multisig/MPC schemes, making the choice of multisig/MPC design critically important to overall Layer2 security.

Merlin adopts Cobo’s MPC service for its bridging solution, employing measures like cold-hot wallet separation. Bridge assets are jointly managed by Cobo and Merlin Chain, with any withdrawal requiring participation from both Cobo and Merlin Chain’s MPC participants. This essentially relies on institutional credibility to ensure bridge reliability. Of course, this is merely a temporary measure; as the project matures, the withdrawal bridge could evolve into an “optimistic bridge” under a 1/N trust model by integrating BitVM and fraud proof protocols. However, implementation would be highly challenging (currently, almost all official Layer2 bridges rely on multisig).

Overall, Merlin integrates a POS-based DAC, an optimistic ZK-Rollup based on BitVM, and an asset custody solution via Cobo’s MPC. It addresses DA through open DAC access, ensures secure state transitions via BitVM and fraud proofs, and maintains withdrawal bridge reliability through Cobo’s reputable MPC infrastructure.

Two-Step Verification ZKP Submission Based on Lumoz

Earlier, we reviewed Merlin’s security model and introduced the concept of optimistic ZK-Rollup. Merlin’s technical roadmap also highlights a decentralized Prover. As widely known, the Prover is a core component in ZK-Rollup architecture, responsible for generating ZK proofs for batches published by the Sequencer. However, generating zero-knowledge proofs is extremely hardware-intensive, posing a significant challenge.

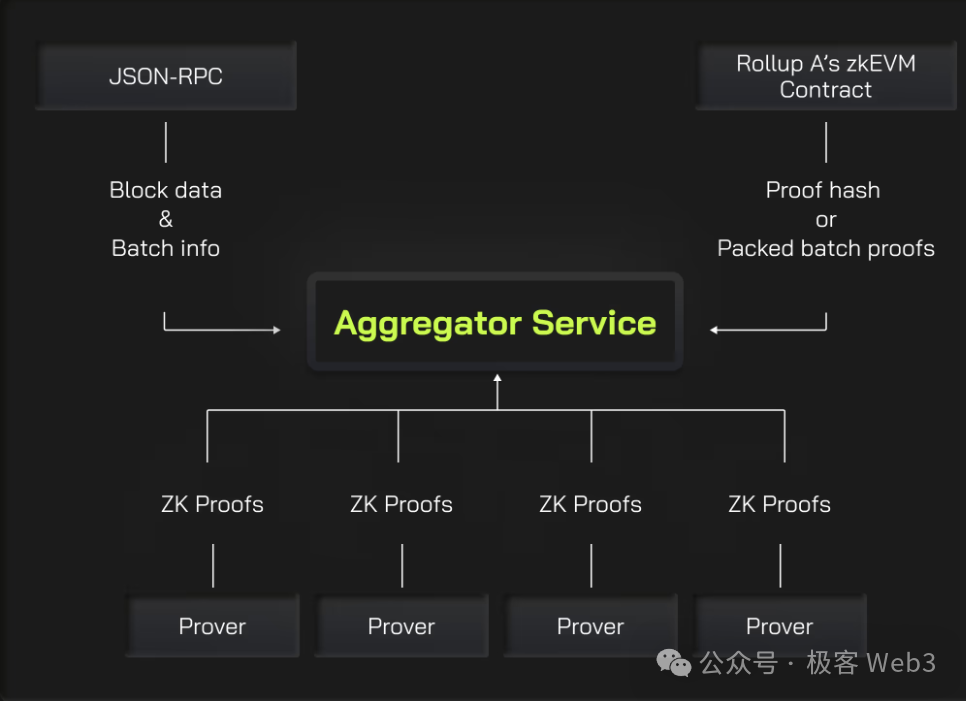

To accelerate ZK proof generation, parallelizing and splitting tasks is fundamental. Parallelization involves dividing the proof generation workload into segments processed by different Provers, with an Aggregator later combining multiple proofs into a single unified proof.

To speed up ZK proof generation, Merlin will adopt Lumoz’s Prover-as-a-Service solution—essentially pooling extensive hardware resources into a mining pool, distributing computational tasks across devices, and allocating rewards accordingly, much like POW mining.

In such a decentralized Prover setup, a known attack vector is front-running: suppose an Aggregator successfully constructs a ZKP and prepares to submit it for reward. Another Aggregator sees the content and rushes to publish the same proof first, claiming it was generated earlier. How can this be prevented?

An instinctive solution might be assigning unique task IDs—for example, only Aggregator A can claim rewards for Task 1. But this creates single-point failure risks: if Aggregator A suffers downtime or performance issues, Task 1 stalls indefinitely. Moreover, assigning tasks to single entities eliminates competitive incentives, reducing production efficiency—an undesirable outcome.

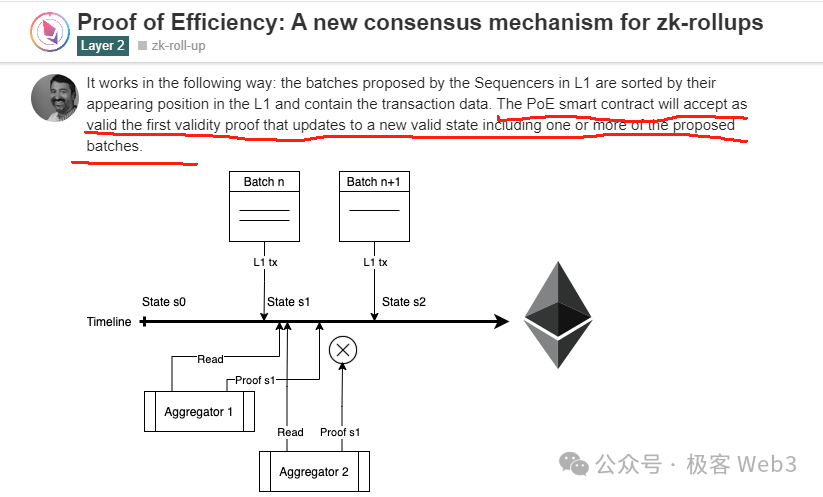

Polygon zkEVM proposed a method called Proof of Efficiency in a blog post, advocating competitive dynamics among Aggregators with first-come-first-served reward allocation: the first to submit a valid ZK proof earns the reward. However, it didn’t address MEV-related front-running attacks.

Lumoz implements a two-step ZK proof submission mechanism. After an Aggregator generates a ZK proof, it doesn’t immediately publish the full content but instead submits only the hash—specifically, hash(ZKP + Aggregator Address). Even if others see the hash, they cannot discern the original ZKP content, preventing direct front-running.

Even if someone copies and resubmits the entire hash, it’s futile because the hash contains the original Aggregator X’s address. If Aggregator A tries to front-run, once the pre-image is revealed, everyone will see the embedded address belongs to X, not A.

Through this two-step verification ZKP submission scheme, Merlin (via Lumoz) mitigates front-running risks during ZKP submission, enabling highly competitive incentive structures and accelerating ZK proof generation.

Merlin’s Phantom: Multi-Chain Interoperability

According to Merlin’s technical roadmap, it will support interoperability between Merlin and other EVM chains, following an approach similar to Zetachain. When Merlin acts as the source chain and another EVM chain as the destination, Merlin nodes detecting a cross-chain request trigger subsequent workflows on the target chain.

For instance, an EOA account controlled by the Merlin network can be deployed on Polygon. When a user issues a cross-chain instruction on Merlin Chain, the Merlin network parses it, generates executable transaction data for the target chain, and uses the Oracle Network to perform MPC signing on the transaction. Then, Merlin’s Relayer node broadcasts the signed transaction on Polygon, executing operations using funds from Merlin’s EOA account on the target chain.

Once the requested operation completes, the resulting assets are forwarded directly to the user’s address on the target chain—potentially even routed back to Merlin Chain. This approach offers clear advantages: it avoids fee slippage associated with traditional cross-chain bridge contracts and relies solely on Merlin’s Oracle Network for security, eliminating dependence on external infrastructure. As long as users trust Merlin Chain, they can assume such cross-chain operations are secure.

Conclusion

In this article, we’ve provided a concise interpretation of Merlin Chain’s overall technical design, aiming to enhance understanding of its workflow and security model. Given the booming Bitcoin ecosystem, such technical education is valuable and widely needed. We will continue long-term coverage of Merlin, BitLayer, B^Square, and similar projects, delivering deeper technical analyses in the future—stay tuned!

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News