Technical Deep Dive: On-Chain IEO Scams Within Scams – Decrypting Large-Scale Rug Pull Tactics

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Technical Deep Dive: On-Chain IEO Scams Within Scams – Decrypting Large-Scale Rug Pull Tactics

This article takes one of the cases as an example to explain in detail the specifics of this exit scam.

Author: CertiK

Recently, the CertiK security team has repeatedly detected multiple identical "exit scams," commonly known as Rug Pulls.

After deep investigation, we found that these similar incidents all trace back to the same group, ultimately linking to over 200 token rug pulls. This suggests we may have uncovered a large-scale, automated hacking team systematically harvesting assets via rug pull schemes.

In these exit scams, attackers create a new ERC20 token and establish a Uniswap V2 liquidity pool using pre-mined tokens along with a certain amount of WETH.

Once on-chain new-token farming bots or users purchase the new token from the liquidity pool a certain number of times, the attacker drains all the WETH from the pool by generating tokens out of thin air.

Since these fraudulently minted tokens do not appear in the total supply (totalSupply) and do not trigger Transfer events, they remain invisible on Etherscan, making detection extremely difficult.

The attackers not only prioritized stealth but also designed a clever misdirection to deceive technically aware users who check Etherscan—masking their true intent behind a seemingly minor flaw...

Inside the Scam

Let us examine one such case in detail to understand how this rug pull operates.

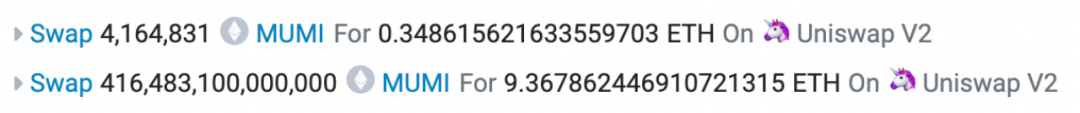

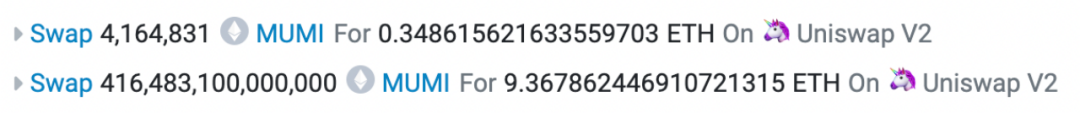

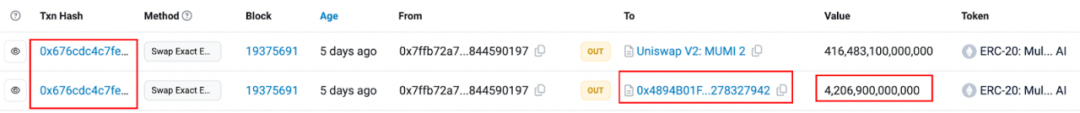

What we initially detected was the transaction where the attacker used a massive amount of secretly minted tokens to drain the liquidity pool and profit. In this transaction, the project team exchanged approximately 416 trillion MUMI tokens for about 9.736 WETH, completely draining the pool's liquidity.

However, this transaction represents only the final step of the entire scam. To fully understand it, we must trace back earlier steps.

Deploying the Token

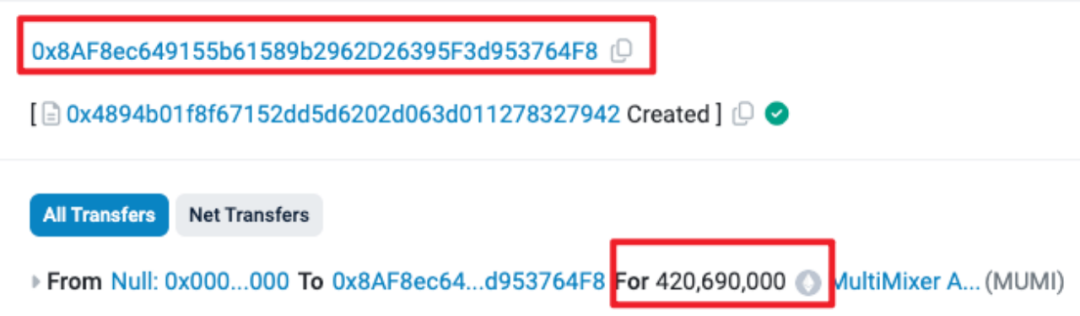

On March 6 at 7:52 AM UTC, the attacker address (0x8AF8) deployed an ERC20 token named MUMI (full name: MultiMixer AI) at address 0x4894, pre-mining 420,690,000 (approximately 420 million) tokens and allocating them entirely to the contract deployer.

The pre-mined supply matches the contract source code.

Adding Liquidity

At exactly 8:00 AM (eight minutes after token creation), the attacker address (0x8AF8) began adding liquidity.

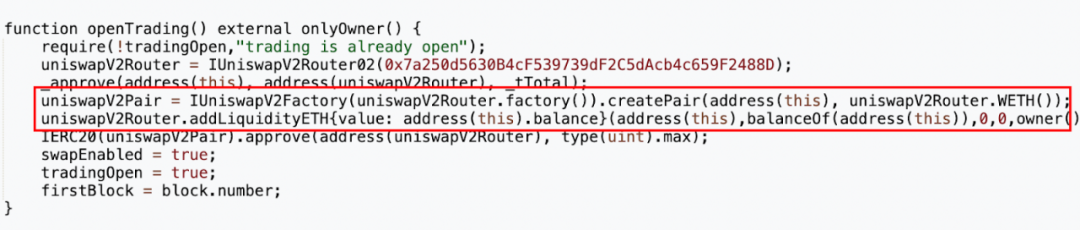

The attacker called the openTrading function within the token contract to create a MUMI-WETH liquidity pool via the Uniswap V2 factory, depositing all pre-mined tokens and 3 ETH into the pool, ultimately receiving approximately 1.036 LP tokens.

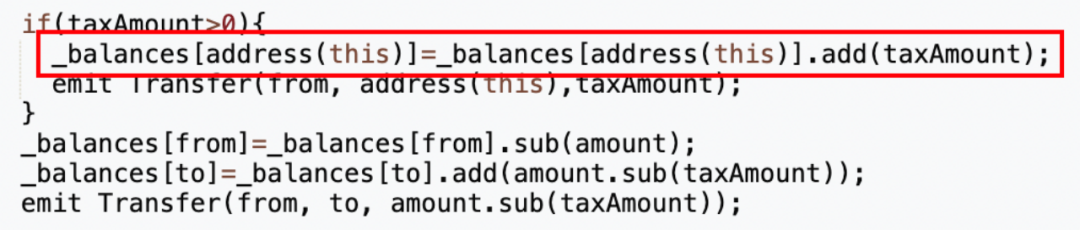

From the transaction details, we can see that out of the original 420,690,000 (approx. 420 million) tokens intended for liquidity provision, 63,103,500 (approx. 63 million) were sent back to the token contract (0x4894). Reviewing the contract code reveals that each transfer incurs a fee, which is collected by the token contract itself (implemented in the _transfer function).

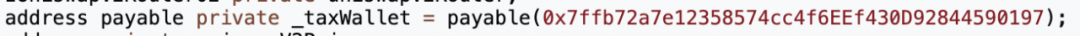

Strangely, although the contract specifies a tax wallet address 0x7ffb (intended recipient of fees), the fees are actually sent to the token contract itself.

As a result, the actual number of MUMI tokens added to the liquidity pool was 357,586,500 (approx. 357 million), after deducting fees, rather than the full 420,690,000 (approx. 420 million).

Locking Liquidity

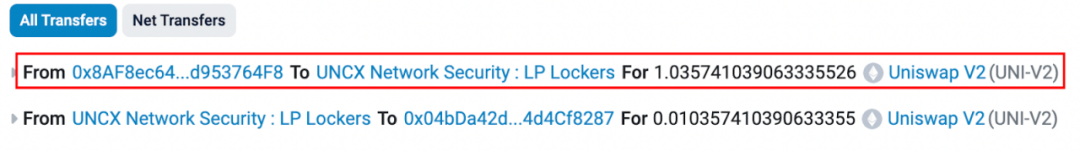

At 8:01 AM (one minute after pool creation), the attacker address (0x8AF8) locked all 1.036 LP tokens obtained from providing liquidity.

Once LP tokens are locked, theoretically, the attacker’s holdings of MUMI tokens are secured within the liquidity pool (excluding those taken as fees), meaning the attacker cannot perform a rug pull by removing liquidity.

To reassure buyers, many projects lock LP tokens to signal commitment—"We won’t run away; feel free to buy!" But is this always true? Clearly not, as demonstrated in this case. Let’s continue our analysis.

Rug Pull Execution

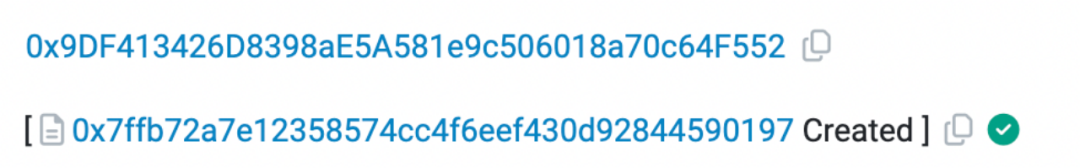

At 8:10 AM, a second attacker address (0x9DF4) appeared and deployed the tax wallet contract at address 0x7ffb declared in the token contract.

Three notable points here:

1. The address deploying the tax contract differs from the one that deployed the token, suggesting intentional efforts to obscure linkages between operations and increase traceability difficulty.

2. The tax contract is not open-sourced, implying potentially hidden malicious logic.

3. The tax contract was deployed after the token contract, yet its address was hardcoded into the token contract. This means the attackers could predict the tax contract’s address in advance. Since CREATE instructions produce deterministic addresses given the creator address and nonce, the attackers likely simulated the deployment beforehand.

Indeed, numerous exit scams leverage tax addresses with deployment patterns matching the above characteristics.

At 11:00 AM (three hours after token creation), attacker address (0x9DF4) executed the rug pull. By calling the 'swapExactETHForTokens' method of the tax contract (0x77fb), they swapped 416,483,104,164,831 (~416 trillion) MUMI tokens for approximately 9.736 ETH, draining the pool’s liquidity.

Since the tax contract (0x77fb) is not open-source, we decompiled its bytecode. The decompiled output is available here:

https://app.dedaub.com/decompile?md5=01e2888c7691219bb7ea8c6b6befe11c

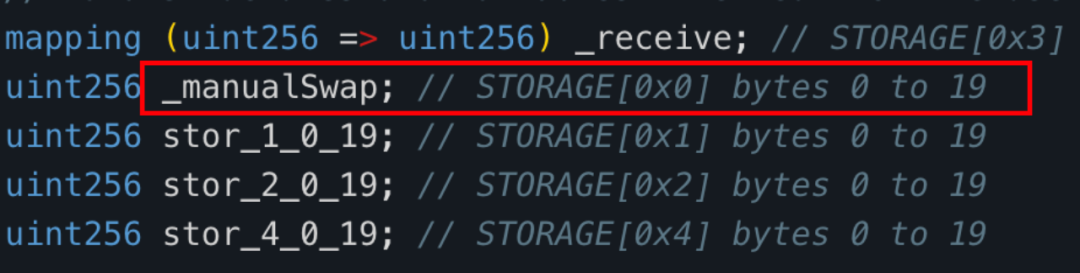

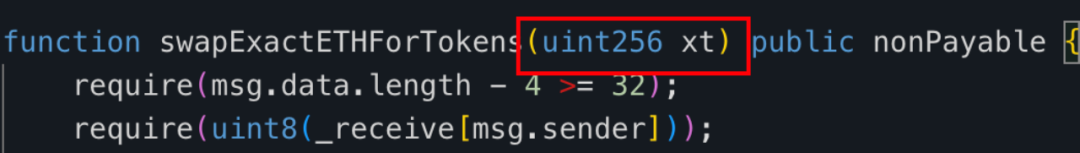

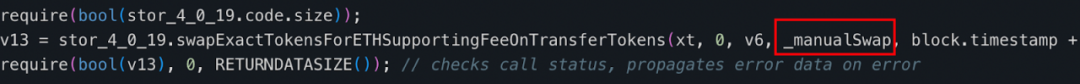

After reviewing the decompiled code of the tax contract’s 'swapExactETHForTokens' function, we found that it primarily uses the UniswapV2 router to swap a specified quantity ('xt') of MUMI tokens held by the tax contract (0x77fb) into ETH and send it to the '_manualSwap' address defined within the tax contract.

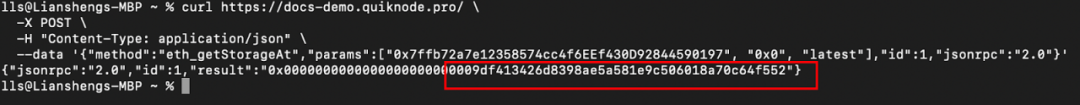

The '_manualSwap' address resides at storage slot 0x0. Querying via JSON-RPC getStorageAt confirms that '_manualSwap' corresponds to the deployer of the tax contract (0x77fb)—attacker #2 (0x9DF4).

The input parameter 'xt' in this rug pull transaction was 420,690,000,000,000,000,000,000, equivalent to 420,690,000,000,000 (~420 trillion) MUMI tokens (MUMI has 9 decimals).

Ultimately, the project team used ~420 trillion MUMI tokens to drain all WETH from the liquidity pool, completing the exit scam.

But here lies a critical question: Where did the tax contract (0x77fb) obtain so many MUMI tokens?

Earlier, we learned that the MUMI token had a total supply of 420,690,000 upon deployment. After the rug pull, querying the MUMI contract still shows the same total supply (displayed as 420,690,000,000,000,000 due to 9 decimals). The tax contract’s balance (~420 trillion) vastly exceeds this—appearing out of nowhere. Recall that 0x77fb never received any transaction fees; those went directly to the token contract.

Uncovering the Mechanism

Origin of Tax Contract Tokens

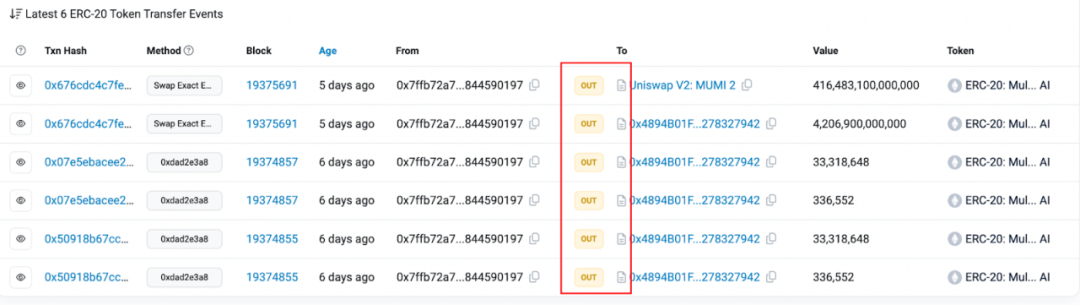

To investigate the source of the tax contract’s tokens, we examined its ERC20 transfer event history.

Among the six transactions involving 0x77fb, only outgoing transfers are recorded—no incoming MUMI transfers. At first glance, the tokens truly seem to materialize from nothing.

Thus, the massive MUMI balance in the tax contract (0x7ffb) exhibits two key traits:

1. No impact on the MUMI contract’s totalSupply

2. Balance increase without triggering Transfer events

This leads us to a clear conclusion: the MUMI contract must contain a backdoor that directly manipulates the balance variable without adjusting totalSupply or emitting Transfer events.

In other words, this is a non-standard—or malicious—ERC20 implementation. Users cannot detect secret mints through total supply changes or events.

To verify, we searched the MUMI contract source code for the keyword “balance.”

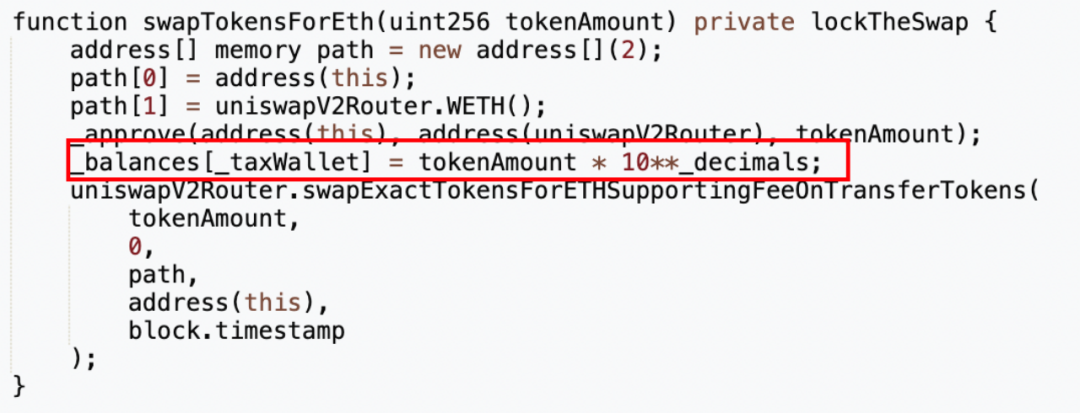

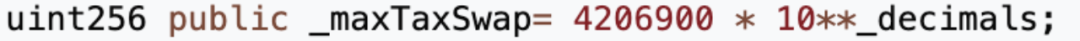

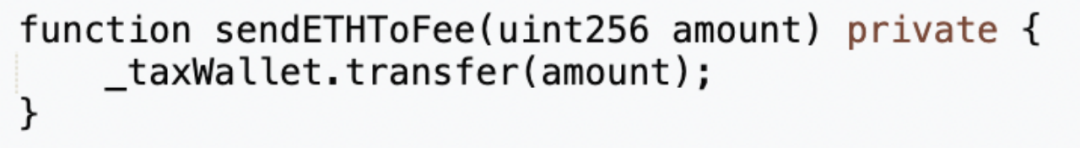

We discovered a private function called 'swapTokensForEth', accepting a uint256 parameter tokenAmount. On line 5, the contract directly sets the balance of _taxWallet (tax contract 0x7ffb) to tokenAmount * 10**_decimals (i.e., one billion times tokenAmount), then swaps tokenAmount worth of MUMI from the pool into ETH, storing it in the token contract (0x4894).

Next, we searched for 'swapTokenForEth'.

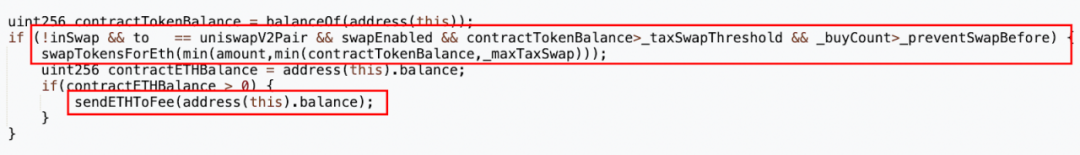

The 'swapTokenForEth' function is called within the '_transfer' function. Examining the conditions:

1. When the recipient address 'to' is the MUMI-WETH liquidity pool.

2. When more than _preventSwapBefore (5) purchases occur in the pool, 'swapTokenForEth' is triggered.

3. The tokenAmount passed is the smaller value between the contract’s current MUMI balance and _maxTaxSwap.

In short, once user trades exceed five times, the contract secretly mints vast quantities of tokens for the tax wallet while swapping some into ETH stored in the token contract.

On the surface, this appears as regular tax collection and conversion—a facade to convince users this is the project’s revenue model.

Behind the scenes, however, the real scheme activates after five trades: directly manipulating balances to drain the entire liquidity pool.

How They Profit

After executing 'swapTokenForEth', the '_transfer' function calls 'sendETHToFee' to transfer the ETH collected as fees from the token contract to the tax contract (0x77fb).

The ETH in the tax contract (0x77fb) can be withdrawn via its internal 'rescue' function.

Now revisit the final profit-making transaction in the rug pull.

Two swaps occurred: first, ~4.16 million MUMI for 0.349 ETH; second, ~416 trillion MUMI for 9.368 ETH. The second swap corresponds to the call within the tax contract’s 'swapExactETHForTokens'. The discrepancy from the input parameter (~420 trillion) arises because part of the tokens were taxed and sent to the token contract (0x4894), as shown below:

The first swap occurs when tokens move from the tax contract to the router, triggering the backdoor condition in the token contract—it is incidental, not core to the exploit.

The Mastermind Behind

As seen above, the MUMI token went from deployment to rug pull in just about three hours, yielding 9.7 ETH with a cost of less than ~6.5 ETH (3 ETH for liquidity, ~3 ETH to make initial purchases as bait, and under 0.5 ETH for deployments and transactions)—a profit margin exceeding 50%.

There were five prior ETH-to-MUMI transactions by the attacker, not previously mentioned:

-

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x62a59ba219e9b2b6ac14a1c35cb99a5683538379235a68b3a607182d7c814817

-

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x0c9af78f983aba6fef85bf2ecccd6cd68a5a5d4e5ef3a4b1e94fb10898fa597e

-

https://etherscan.io/tx/0xc0a048e993409d0d68450db6ff3fdc1f13474314c49b734bac3f1b3e0ef39525

-

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x9874c19cedafec351939a570ef392140c46a7f7da89b8d125cabc14dc54e7306

-

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x9ee3928dc782e54eb99f907fcdddc9fe6232b969a080bc79caa53ca143736f75

Analyzing EOAs interacting with the liquidity pool revealed many were on-chain “new-token farming bots.” Given the scam’s rapid execution, we believe the primary targets were precisely these active farming bots and scripts.

Hence, every complex contract design choice, deployment sequence, and liquidity locking step—even the attacker’s own trades—were likely crafted to bypass anti-fraud checks in farming bots.

Tracing fund flows, we found all profits eventually sent to a consolidation address (0xDF1a) by attacker #2 (0x9dF4).

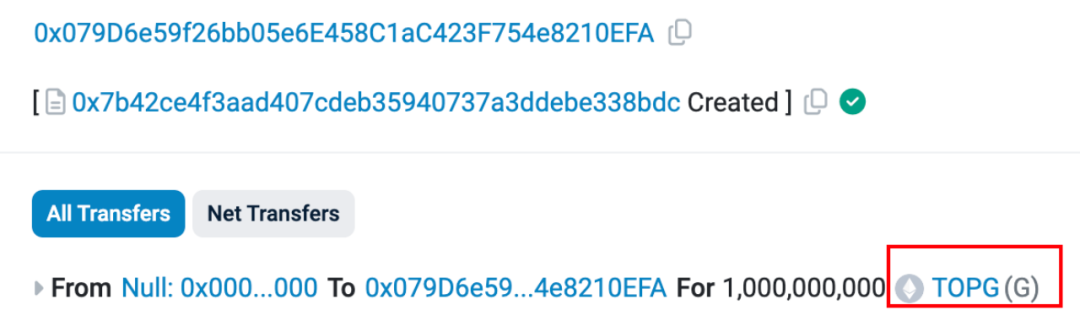

In fact, recent rug pulls we’ve detected share common funding sources and final destinations pointing to this same address. We conducted preliminary analysis and statistics on its transactions.

We found the address became active about two months ago and has since executed over 7,000 transactions, interacting with more than 200 tokens.

Analyzing around 40 of these tokens, nearly all showed a final swap transaction with input volume far exceeding total supply, draining ETH from the pool—all within short timeframes.

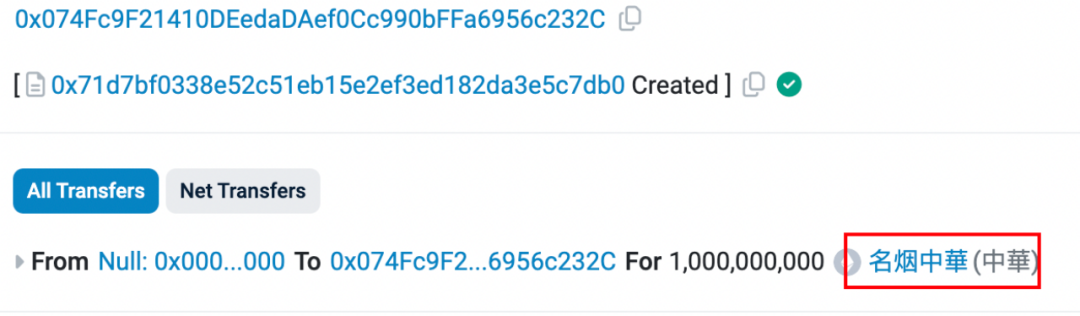

Sample deployment transactions for some tokens (e.g., "Famous Cigarette Zhonghua"):

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x324d7c133f079a2318c892ee49a2bcf1cbe9b20a2f5a1f36948641a902a83e17

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x0ca861513dc68eaef3017e7118e7538d999f9b4a53e1b477f1f1ce07d982dc3f

Therefore, we conclude this address functions as a large-scale automated “rug pull harvesting machine,” specifically targeting on-chain farming bots.

This address remains active.

Final Thoughts

If a token allows minting without updating totalSupply or emitting Transfer events, it becomes nearly impossible to detect secret mints—exacerbating the problem where token safety depends solely on the issuer’s honesty.

We may need to reconsider current token standards or introduce effective mechanisms for monitoring total supply changes to ensure transparency. Relying solely on events to track token state changes is no longer sufficient.

Moreover, we must remain vigilant: while public awareness of scams improves, attackers evolve faster. This is an endless arms race. Only through continuous learning and critical thinking can we protect ourselves in this ongoing battle.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News