The Principle, Current State, and Future of Sequencers

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Principle, Current State, and Future of Sequencers

What is a sequencer, and how does it work in Layer2?

Author: Uncle Jian

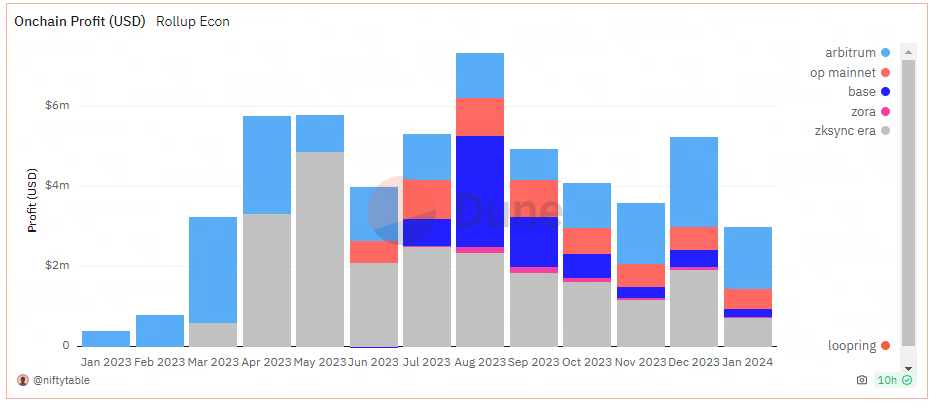

Currently, the main source of revenue for Layer2 solutions comes from gas fees paid by users when conducting transactions on Rollups. After subtracting the gas fees paid to submit data back to Layer1, what remains is nearly pure profit. As shown in the chart below, OP Mainnet earned approximately $5.23 million in profit from June to December 2023, Arbitrum made $16.5 million in annual profits, and zkSync Era generated $22.24 million in profit from March to December 2023.

What's the secret behind such massive profits? It largely relates to their use of a single, centralized sequencer.

So, what exactly is a sequencer, and how does it function within Layer2? What problems arise with centralized sequencers, and how might they evolve in the future? This article will explore these questions in depth.

How Sequencers Work

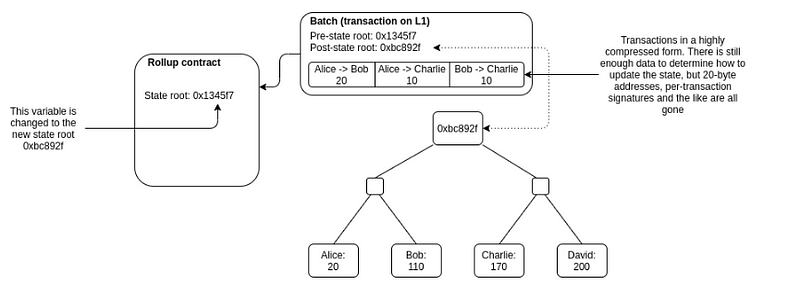

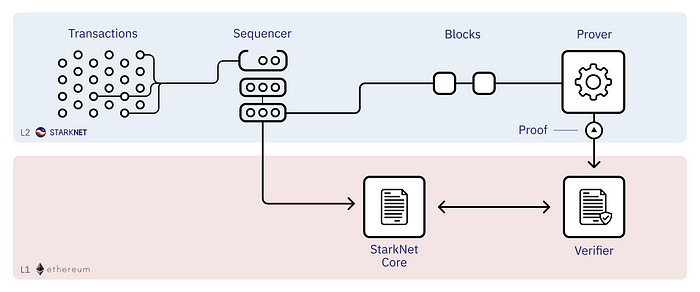

A "sequencer," also known as a "batcher," plays a critical role in Layer2 systems. Its primary functions include receiving user transactions from Layer2, executing them, and then submitting batches of ordered and compressed transactions to Layer1.

This may still sound abstract, so let’s illustrate it with an analogy. When users transact directly on Ethereum, it's like driving your own car into the city (Ethereum). During peak hours, traffic jams naturally occur. At such times, unless you're willing to pay more to get priority access (via validators), you have no choice but to wait.

In real life, there are many ways to alleviate traffic congestion—developing public transit, widening roads, building bypasses, or staggering travel times. Layer2 serves as Ethereum’s public transportation solution, and the sequencer acts as the bus driver. The bus driver tells everyone: “You don’t need to drive yourself anymore. Just pay me a small service fee (much lower than self-driving), and I’ll get you to your destination.” This saves both time and money. To maximize space utilization, the driver waits until the bus is full before departing and strategically arranges passengers—for example, squeezing a thinner person between two heavier ones—to fit everyone tightly inside.

With this analogy in mind, let's address some common questions.

Who Can Run a Sequencer?

There are several common models:

-

Centralized Sequencer

In this model, the Layer2 team or a designated organization exclusively operates the sequencer. Due to its high efficiency and low cost, this approach is favored by most Layer2 teams.

Other models exist as well, which we will discuss further in the section on decentralized sequencers.

-

Fully Permissionless Sequencer

This means anyone can order transactions and submit batches to Layer1. While seemingly fair and open, this model has clear drawbacks. Unlike miners or validators on Layer1, sequencers do not enhance security—they simply submit transaction batches. Even if multiple parties simultaneously submit batches, only one will be accepted, leading to significant waste of computational resources and gas fees across redundant submissions.

On What Basis Do Sequencers Order Transactions?

Typically, there are two main approaches. One is First-Come-First-Served (FCFS), similar to boarding a bus—the earlier you arrive, the better your seat. The other prioritizes based on gas fees: users who want faster processing can pay extra, prompting the sequencer to prioritize their transactions regardless of arrival time.

Most mainstream Layer2 networks adopt the FCFS method. However, neither method is strictly mandated—Layer2 protocols impose no hard rules on ordering. In theory, a sequencer could arbitrarily reorder transactions, just as a bus driver might refuse someone entry or reserve seats for relatives, even if it seems unfair.

Can Sequencers Misbehave? How Can We Prevent That?

Theoretically, yes, sequencers can act maliciously.

Sequencers hold substantial power. They could deliberately drop a user’s transaction while falsely claiming it was executed, or insert a malicious transaction (e.g., transferring a user’s Layer2 assets to their own address) for personal gain.

To prevent such behavior, different Layer2 designs implement various safeguards. Optimistic Rollups use fraud proofs: assuming honesty initially, submitted data becomes final after a challenge period (typically one week), unless a validator proves it incorrect. ZK Rollups employ validity proofs: every batch submitted by the sequencer is immediately verified, ensuring instant finality on Layer1 without any dispute window.

Starknet sequencer operation diagram

Current State: Problems Caused by Centralized Sequencers

Currently, major Layer2 platforms—including OP Mainnet, Arbitrum One, Starknet, and zkSync Era—use centralized sequencers operated by official teams or affiliated organizations. For example, the Optimism Foundation runs the OP Mainnet sequencer, and Offchain Labs manages Arbitrum One’s sequencer.

Centralized sequencers offer Layer2 projects numerous advantages: easier management, higher efficiency, and direct revenue generation. Although most claim to uphold user interests and avoid misconduct (currently adhering strictly to FCFS), many users remain concerned about centralization risks.

Weak Censorship Resistance

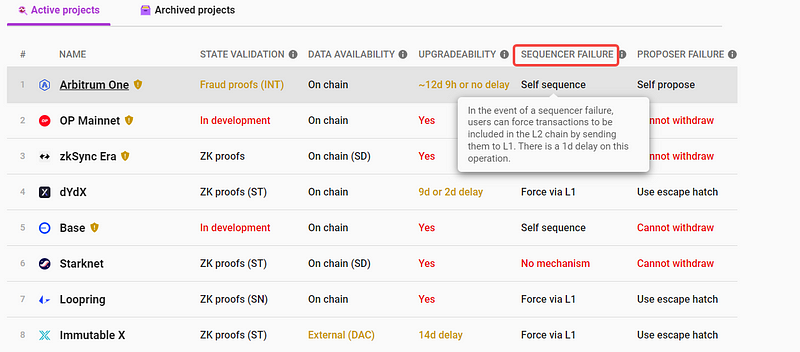

Since a single centralized entity controls the sequencer, censorship resistance is far weaker than on Layer1, where thousands of miners or validators distribute control. Teams might exclude certain transactions due to regulatory pressure or blacklist specific addresses. While most Layer2s provide mechanisms allowing users to bypass the sequencer and submit transactions directly to Layer1, doing so incurs additional costs.

Alternative path for direct user submission (Source: L2BEAT)

Weak Liveness

Weak liveness refers to single points of failure. Compared to Layer1 handling tens of thousands of transactions per second, a centralized sequencer may struggle under heavy load due to hardware limitations. Without backup sequencers, system-wide outages can occur—such as during Arbitrum’s airdrop distribution.

Improper MEV Extraction

MEV, or Maximal Extractable Value, refers to the profit miners/validators can extract by manipulating transaction order (inserting, removing, reordering). Typically, transactions are ordered by gas price, but when large profits appear (e.g., arbitrage opportunities), miners can front-run trades—adding their own transactions, censoring others, or reordering—to capture value beyond block rewards. This is often described as “being both player and referee.”

In Layer2, sequencers similarly possess the power to manipulate transaction order. Although operated by trusted teams, complete trust cannot be assumed—especially since OP Mainnet uses a private mempool (a temporary storage for pending transactions), effectively creating a black-box environment. While justified as preventing others from monitoring and extracting MEV, this opacity raises concerns.

The Future

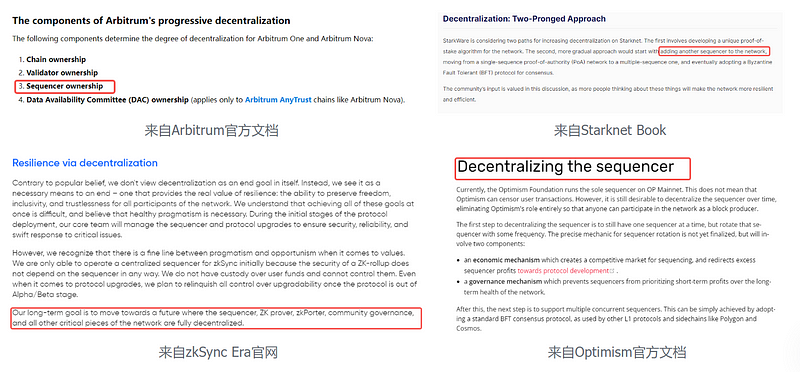

Mainstream Layer2 platforms (OP Mainnet, Arbitrum One, Starknet, zkSync Era) are aware of the issues posed by centralized sequencers and have proposed plans for decentralized sequencers.

However, these proposals currently exist only in whitepapers or documentation. Compared to decentralizing power and revenue, most teams appear more focused on strengthening core competitiveness—network performance and ecosystem development.

Decentralized Sequencer Models

Below are brief descriptions of several decentralized sequencer approaches:

-

Geographic Decentralization

A straightforward method involving deploying multiple sequencers across different geographic locations, each run by reputable, stake-aligned organizations. They take turns sequencing transactions over fixed periods. While imperfect, this improves censorship resistance and liveness compared to a single centralized node.

-

Sequencer Auctions

Rollups could use smart contracts to auction off sequencer rights. Anyone can bid for the right to sequence, either per-block or for time windows. Winners must stake collateral to deter malicious behavior, and proceeds from auctions can be redistributed within the network.

-

Leader Election

Anyone can stake tokens (ETH or native Layer2 tokens) into a contract. For each batch submission, a leader is randomly selected from stakers—with selection probability proportional to stake size.

-

Based Rollup

A recent idea emerging in the Ethereum community: letting Ethereum validators directly handle Layer2 transaction ordering, completely replacing dedicated Layer2 sequencers. This model is technically more complex and faces unresolved challenges.

Shared Sequencers

Decentralized sequencer models focus on distributing sequencing authority among participants while keeping Layer2 teams in control. Shared sequencers go further: eliminating individual Layer2-specific sequencers altogether and having multiple Layer2s share a third-party sequencing network.

This offers benefits such as atomic composability across Layer2s (transactions from different rollups sharing the same mempool) and better MEV mitigation. Several projects—including Astria, Radius, and Espresso—are actively developing shared sequencing networks.

Conclusion and Reflection

Eliminating single points of failure and mitigating systemic risk aligns with core crypto principles. The push toward decentralized sequencers reflects this ethos. But from a practical standpoint, can decentralized or shared sequencers truly solve the problems caused by centralization today? Not necessarily.

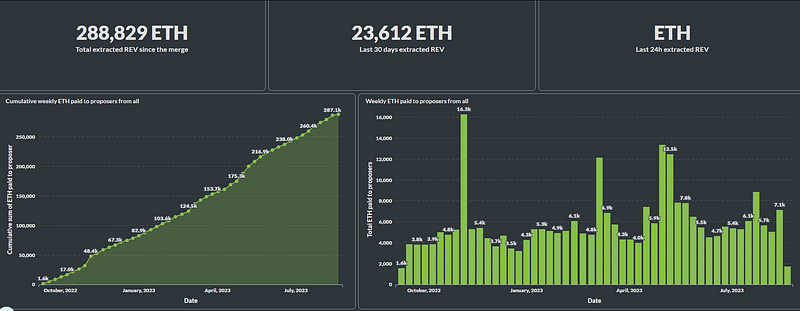

From an MEV perspective, consider Ethereum: according to Flashbots, since The Merge, proposers have extracted 288,829 ETH in realized value (REV). (Note: REV refers to already captured MEV.)

And this is just partial data from Flashbots. The scale of MEV in permissionless Ethereum is clearly enormous.

Benign arbitrage-driven MEV contributes to market stability. However, the lure of large MEV profits incentivizes harmful behaviors like sandwich attacks, negatively impacting the network. Even if validators themselves don't misbehave, off-chain collusion and bribery markets may emerge. This contradicts Ethereum’s original ideals and harms ordinary users. While Ethereum is exploring solutions (like separating proposers from builders), the issue persists in the short term.

Today’s MEV landscape evolved organically through market forces. If Rollup sequencers become equally open and decentralized, could a similar dynamic eventually form? Rather than trusting a single Rollup team (with associated single-point risks), would we instead face chaotic competition and new forms of centralization? These possibilities are concerning.

Moreover, while shared sequencers enable interoperability at the sequencing layer, widespread adoption of third-party shared networks could concentrate immense power in a few entities controlling multiple Rollups. Wouldn’t this recreate the very centralization we aim to avoid? And if so, do we then need mechanisms to decentralize the shared sequencers themselves? These are important questions that require deeper consideration.

Blockchain evolution and decentralization are long, difficult journeys. The attention given to sequencers stems from their pivotal role in the Rollup architecture. With continued exploration and effort, we can hope that today’s challenges will eventually find suitable solutions.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News