Prospective High-Potential Sector: Decentralized Computing Power Market (Part 2)

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Prospective High-Potential Sector: Decentralized Computing Power Market (Part 2)

This article will start from the fundamental concepts of zero-knowledge proofs and progressively delve into multidimensional considerations of the promising decentralized computing market, exploring its broader possibilities.

Author: Zeke, Researcher at YBB Capital

Preface

In "Emerging Sector Outlook: Decentralized Computing Power Market (Part 1)", we have already explored the importance of computing power under AI expectations and deeply discussed two major challenges in building a decentralized AGI computing market at this stage. This article will start from the basic concepts of zero-knowledge proofs, progressing from simple to complex, offering multidimensional insights into the promising赛道 of decentralized computing markets. (The previous article briefly mentioned Bitcoin's computing market; however, given the recent explosive growth of the Bitcoin ecosystem, that section will be covered in future articles dedicated to the Bitcoin ecosystem.)

Overview of Zero-Knowledge Proofs

In the mid-1980s, three cryptographers from MIT—Shafi Goldwasser, Silvio Micali, and Charles Rackoff—co-published a paper titled "The Knowledge Complexity of Interactive Proof Systems." The paper described an innovative cryptographic technique capable of verifying information authenticity without revealing the actual content, which the authors named "zero-knowledge proof," providing a concrete definition and framework for this concept.

Over subsequent decades, building upon this foundational work, zero-knowledge proof technology gradually evolved and improved across multiple domains. Today, zero-knowledge proof has become an umbrella term representing many aspects of “modern” or “advanced” cryptography—particularly those related to the future of blockchain.

Definition

Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP), hereinafter referred to as such depending on context, refers to a method where a prover can convince a verifier of the correctness of a statement without disclosing any specific details about the statement itself. This approach is characterized by three fundamental properties: completeness, soundness, and zero-knowledge. Completeness ensures that true statements can be proven; soundness guarantees that false statements cannot be falsely verified; and zero-knowledge means that the verifier learns nothing beyond the truth of the statement.

Types of Zero-Knowledge Proofs

Depending on the communication mode between the prover and verifier, there are two types of zero-knowledge proofs: interactive and non-interactive. In interactive proofs, the prover and verifier engage in a series of interactions. These exchanges form part of the proof process, with the prover responding to a sequence of queries or challenges from the verifier to demonstrate the validity of their claim. This typically involves multiple rounds of communication, with the verifier posing questions or challenges each round, and the prover responding accordingly. Non-interactive proofs, on the other hand, do not require repeated interaction. Here, the prover creates a single, independently verifiable proof and sends it to the verifier. The verifier can then validate the proof’s authenticity without further communication with the prover.

Plain Explanation of Interactive vs. Non-Interactive ZKPs

1. Interactive: The story of Alibaba and the Forty Thieves is a classic example often used to explain interactive zero-knowledge proofs, with many variations. Below is my simplified adaptation.

Alibaba knows the incantation to open a cave hiding treasure but is captured by the forty thieves who demand he reveal the spell. If Alibaba reveals the spell, he loses his value and will be killed. If he refuses, the thieves won’t believe he truly knows the spell and will also kill him. But Alibaba devises a clever solution. The cave now has two entrances, A and B, both leading to the center, but a secret door blocks passage through the center—only someone knowing the incantation can pass. To prove knowledge of the secret without revealing it, Alibaba enters the cave and randomly chooses entrance A or B, while the thieves remain outside and cannot see his choice. Then, the thieves randomly shout either A or B, demanding Alibaba exit from that entrance. If Alibaba truly knows the incantation, he can use it to cross the central door and emerge from the designated entrance. Repeating this process multiple times, Alibaba consistently exits from the requested entrance, thereby proving his knowledge of the password without ever revealing it.

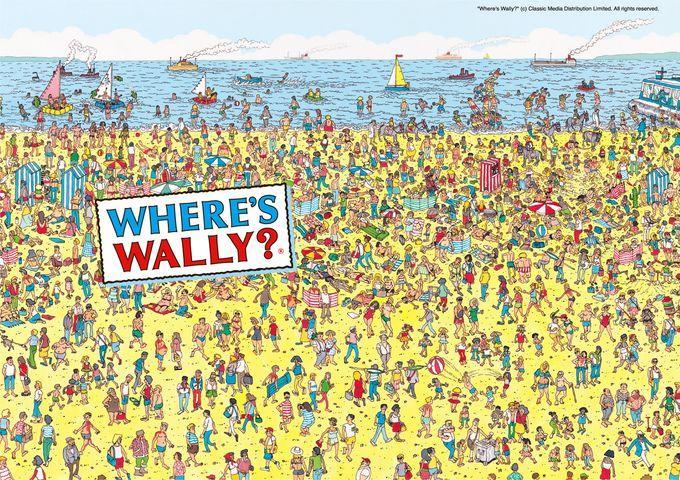

2. Non-Interactive: Here's a real-life analogy of a non-interactive zero-knowledge proof. Imagine you and a friend both have a "Where’s Waldo?" book. You claim to know Waldo’s location on a certain page, but your friend doubts you. To prove your knowledge without revealing the exact spot, you could cover the entire image with a large opaque sheet and cut a small hole just over Waldo (a single, independently verifiable proof). This way, you prove you know where Waldo is, yet your friend still doesn't know his precise coordinates within the image.

Technical Implementation in Blockchain

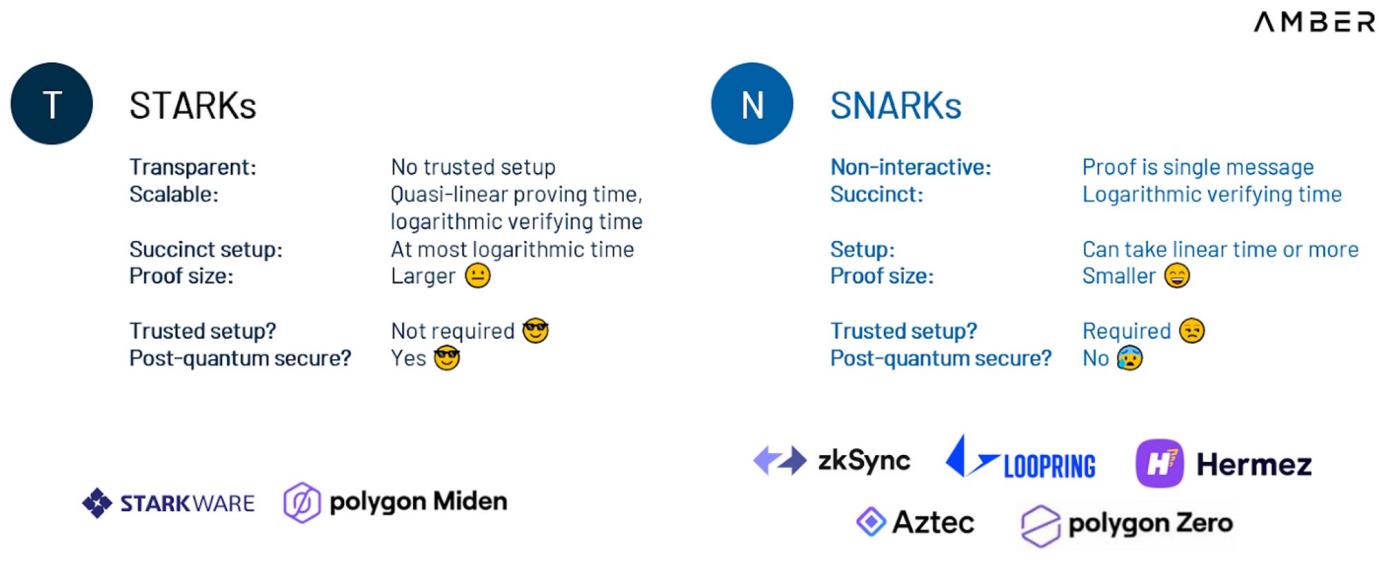

Currently, zero-knowledge proofs are implemented in various ways on blockchains, with zk-STARK (Zero-Knowledge Scalable Transparent Argument of Knowledge) and zk-SNARK (Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge) being the most well-known. As indicated by the term "Non-Interactive" in their names, both belong to the category of non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs.

zk-SNARK belongs to a class of widely applicable general-purpose zero-knowledge proof schemes (note that zk-SNARK refers to a school of thought rather than a single technology). It converts arbitrary computations into circuits, leverages mathematical properties of polynomials to compress these circuits into compact non-interactive proofs, enabling applications across diverse complex business scenarios. zk-SNARK requires a trusted setup—a process where multiple parties generate partial keys to initialize the network and then destroy the original key material. If the secret information used during this trusted setup isn’t properly destroyed, it could be exploited to forge transactions via fake verification.

zk-STARK represents an evolution of zk-SNARK, addressing its reliance on trusted setups. zk-STARK operates without requiring any trusted initialization, thus reducing deployment complexity and eliminating collusion risks. However, zk-STARK suffers from larger proof sizes, making it less efficient in terms of storage, on-chain verification, and generation time. If you've tried early versions of StarkNet (a Layer 2 using zk-STARK), you’d likely notice significantly slower speeds and higher gas fees compared to other Layer 2 solutions. Therefore, zk-SNARK remains more widely adopted today. Other less common alternatives include PLONK and Bulletproofs, each presenting different trade-offs regarding proof size, proving time, and verification speed. Achieving a perfect zero-knowledge proof is extremely difficult, and mainstream algorithms constantly balance across various dimensions.

Developing ZK systems typically requires two key components:

ZK-Friendly Computation Expression Methods: This refers to domain-specific languages (DSLs) or low-level libraries. Libraries like Arkworks provide essential tools and primitives, allowing developers to manually rewrite code in lower-level languages. DSLs such as Cairo or Circom are programming languages tailored specifically for ZK applications. They compile down to the primitives needed for proof generation. More complex operations lead to longer proof generation times, and certain operations (like bitwise operations in SHA or Keccak) may be ill-suited for ZK, resulting in prolonged proof creation.

Proof System: The proof system is the core of any ZK application, implementing two primary functions: Prove and Verify. The Prove function generates a proof (requiring intensive mathematical computation—the more complex the proof, the slower the generation), demonstrating the correctness of a statement without revealing underlying details. The Verify function checks the validity of this proof (more complex or larger proofs demand higher performance but result in shorter verification times). Different proof systems—such as Groth16, GM17, PLONK, Spartan, and STARK—vary in efficiency, security, and usability.

ZKP Application Landscape

-

ZKP Cross-Chain Bridges and Interoperability: ZKPs can create validity proofs for cross-chain messaging protocols, enabling fast verification on target chains. This resembles how zkRollups are validated on base L1s. However, cross-chain messaging introduces greater complexity due to differing signature schemes and cryptographic functions between source and destination chains;

-

ZKP On-Chain Gaming Engines: Dark Forest demonstrates how ZKPs enable incomplete-information games on-chain. This is crucial for designing more interactive games where players’ actions remain private until they choose to reveal them. As on-chain gaming matures, ZKPs will become integral parts of game execution engines. Startups successfully integrating privacy features into high-throughput on-chain gaming platforms stand to gain significant advantages;

-

Identity Solutions: ZKPs unlock numerous opportunities in identity management. They can enable reputation proofs or bridge Web2 and Web3 identities. Currently, our Web2 and Web3 identities are separate. Projects like Clique use oracles to connect them. ZKPs can advance this further by enabling anonymous linking between Web2 and Web3 identities. Use cases include anonymous DAO membership conditional on proving domain expertise via Web2 or Web3 data. Another case is uncollateralized Web3 lending based on a borrower’s Web2 social status (e.g., number of Twitter followers);

-

ZKP for Regulatory Compliance: Web3 enables anonymous online accounts to actively participate in financial systems, achieving unprecedented financial freedom and inclusion. As Web3 regulation increases, ZKPs can help achieve compliance without compromising anonymity. For instance, ZKPs can prove that a user is not a citizen or resident of a sanctioned country. They can also verify accredited investor status or meet other KYC/AML requirements;

-

Native Web3 Private Debt Financing: TradFi debt financing often supports growing startups in accelerating growth or launching new ventures without additional venture capital. The rise of Web3 DAOs and anonymous companies creates opportunities for native Web3 debt financing. For example, using ZKPs, DAOs or anonymous entities can obtain unsecured loans at competitive rates based on proofs of growth metrics, without disclosing borrower information to lenders;

-

Private DeFi: Financial institutions often keep transaction histories and exposures confidential. However, using DeFi protocols on-chain makes fulfilling this need challenging due to advances in on-chain analytics. One possible solution is developing privacy-focused DeFi products to protect participants' privacy. Protocols like Penumbra’s zkSwap aim to achieve this. Additionally, Aztec’s zk.money offers private DeFi earning opportunities by obscuring user participation in transparent DeFi protocols. Generally, protocols successfully implementing efficient, privacy-centric DeFi products can attract substantial volume and revenue from institutional participants;

-

ZKP for Web3 Advertising: Web3 empowers users to own their data rights—browsing history, private wallet activity, etc.—and monetize this data. Since data monetization may conflict with privacy, ZKPs play a critical role in controlling what personal data is disclosed to advertisers and data aggregators;

-

Private Data Sharing and Monetization: Many private datasets could have significant impact if shared with the right entities. Personal health data crowdsourced could aid researchers in drug development. Private financial records shared with regulators and watchdogs could help identify and punish corruption. ZKPs enable private sharing and monetization of such data;

-

Governance: With the popularity of DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) and on-chain governance, Web3 is moving toward direct participatory democracy. A major flaw in current governance models is non-private participation. ZKPs can serve as a foundational fix—participants can vote without revealing how they voted. Moreover, ZKPs can restrict visibility of governance proposals to only DAO members, helping DAOs build competitive advantages.

-

zkRollup: Scaling is the most important use case of ZKPs in blockchain. zkRollup technology aggregates multiple transactions into one. These transactions are processed off-chain (outside the main blockchain). Using ZKPs, zkRollups generate a proof attesting to the validity of these aggregated transactions without revealing their contents, significantly compressing data size. The generated ZKP is then submitted to the main chain. Nodes on the main chain only need to verify the proof instead of processing every individual transaction, greatly reducing the main chain’s load.

ZKP Hardware Acceleration

Although zero-knowledge proof protocols offer many advantages, the main current issue is that verification is easy, but proof generation is hard. The primary bottleneck in most proof systems lies in multi-scalar multiplication (MSM) or fast Fourier transform (FFT) and its inverse. Their composition and trade-offs are outlined below.

Multi-Scalar Multiplication (MSM): MSM is a key computation in cryptography involving scalar multiplication of points on elliptic curves. In ZKPs, MSM helps construct complex mathematical relationships about points on elliptic curves. These calculations often involve massive datasets and operations, forming critical parts of proof generation and verification. MSM is particularly important in ZKPs because it enables constructing proofs that verify encrypted claims without exposing private information. MSM can run across multiple threads, supporting parallel processing. However, when handling large vectors—say 50 million elements—multiplication remains slow and demands substantial memory. Additionally, MSM faces scalability challenges—even with extensive parallelization, performance gains plateau.

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): FFT is an efficient algorithm for computing polynomial multiplication and solving polynomial interpolation problems. In ZKPs, it optimizes polynomial computation, a vital step in proof generation. By breaking down complex polynomial operations into smaller, simpler components, FFT accelerates computation—crucial for proof generation efficiency. Its use dramatically enhances ZKP systems’ ability to handle complex polynomials and large datasets. However, FFT relies heavily on frequent data exchange, making it difficult to significantly boost efficiency via distributed computing or hardware acceleration. FFT operations demand high bandwidth, especially when processing datasets exceeding hardware memory capacity.

While software optimization remains an important research direction, the most direct and brute-force way to accelerate proof generation today is stacking sufficient computational power via hardware. Among various computing hardware options (GPU, FPGA, ASIC), which is the best choice? Since we briefly introduced GPUs in the previous section, here we focus on understanding the design logic and pros/cons of FPGAs and ASICs.

ASIC: An Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) is an integrated circuit designed specifically to meet particular application needs. Compared to general-purpose processors or standard ICs, ASICs are customized for specific tasks, delivering superior efficiency and performance within their intended use. In the well-known field of Bitcoin mining, ASICs are crucial computing devices, whose high efficiency and low power consumption make them ideal for Bitcoin mining. However, ASICs have two clear drawbacks: being purpose-built (e.g., Bitcoin ASIC miners are all designed around the SHA-256 hashing algorithm), they incur high design and manufacturing costs unless produced at scale, along with long design and validation cycles.

FPGA: FPGA stands for Field Programmable Gate Array—an reprogrammable device developed from traditional logic circuits like PAL (Programmable Logic Array), GAL (Generic Array Logic), and CPLD (Complex Programmable Logic Device). Like ASICs, FPGAs are integrated circuits used in electronic design to implement specific functionalities. They overcome limitations of earlier semi-custom circuits while surpassing fixed gate counts of prior programmable devices. Key features include "reprogrammability, low power, low latency, strong computing power." However, FPGAs rely entirely on hardware implementation—they cannot perform operations like conditional branching and support only fixed-point arithmetic. Cost-wise, FPGA design costs are lower than ASICs, though manufacturing depends on scale. Still, both generally cost far more than GPUs.

Returning to ZKP hardware acceleration, we must first acknowledge that ZKP technology is still in its early stages. System parameters (e.g., FFT width or bit size of elements) and choice of proof systems (five were mentioned above alone) lack standardization. Let’s compare the three computing hardware types in this context:

-

Changes in ZK "Meta": As previously noted, ASICs have hard-coded logic. Any change in ZKP logic requires starting over. FPGAs can be reprogrammed instantly and repeatedly—meaning the same hardware can be reused across chains with incompatible proof systems (e.g., cross-chain MEV extraction) and flexibly adapt to shifts in ZK "meta." While GPUs aren’t as rapidly reconfigurable at the hardware level as FPGAs, they offer great flexibility at the software layer. GPUs can adapt to different ZKP algorithms and logic changes via software updates. Though slower than FPGA reconfiguration, such updates can still be completed relatively quickly.

-

Supply Chain: Designing, manufacturing, and deploying ASICs typically takes 12–18 months or longer. In contrast, FPGA supply chains are healthier—leading vendors like Xilinx allow bulk retail orders delivered in 16 weeks directly from websites (no human contact required). GPUs naturally enjoy massive supply advantages—after Ethereum’s Shanghai upgrade, vast numbers of idle GPU miners exist globally. Future GPU series from Nvidia and AMD will also ensure abundant supply.

From these two perspectives, unless consensus forms around a standardized ZK approach, ASICs hold no advantage. Given the current diversity in ZKP schemes, GPUs and FPGAs will remain the two primary computing hardware candidates for discussion.

-

Development Cycle: Due to widespread adoption and mature development tools like CUDA (for NVIDIA GPUs) and OpenCL (cross-platform), GPU development is easier. FPGA development usually involves complex hardware description languages (e.g., VHDL or Verilog), requiring longer learning and development periods;

-

Power Consumption: FPGAs generally outperform GPUs in energy efficiency. This stems from FPGAs’ ability to optimize for specific tasks, minimizing wasted energy. GPUs deliver powerful performance on highly parallel tasks but at the cost of higher power draw;

-

Customizability: FPGAs can be programmed to optimize specific ZKP algorithms, improving efficiency. In contrast, GPUs’ general-purpose architecture may be less efficient for specialized ZKP tasks;

-

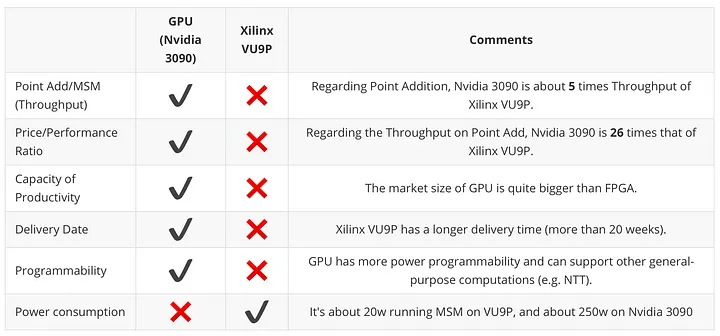

Generation Speed: According to Trapdoor-Tech’s comparison between GPU (Nvidia 3090) and FPGA (Xilinx VU9P) under BLS12-381 (a specific type of elliptic curve) using identical modular multiplication/addition algorithms, GPU proof generation speed is five times faster than FPGA.

In summary, in the short term, considering development cycle, parallelism, generation speed, cost, and the vast amount of readily available idle equipment worldwide, GPUs are clearly the most advantageous option. Current hardware optimization efforts primarily focus on GPUs, and the era of FPGA dominance has yet to arrive. So, is it possible to build a ZKP computing market akin to PoW mining (a term I personally coined)?

Thoughts on Building a ZKP Computing Market

Regarding hardware for building a ZKP computing market, we’ve drawn conclusions from the above. Remaining questions are: Does ZKP need decentralization? Is the market size attractive? And if all ZK-based blockchains choose to build their own proof-generation markets, what purpose does a standalone ZKP computing market serve?

Significance of Decentralization: First, most current zkRollup projects (e.g., Starkware and zkSync) rely on centralized servers, as they only consider Ethereum scaling. Centralization implies ongoing censorship risk, partially sacrificing blockchain’s core permissionless nature. For privacy-preserving ZK protocols, decentralizing proof generation is even more essential. A second reason is cost—similar to the AGI section above. Cloud services and hardware procurement are prohibitively expensive, limiting proof generation to large-scale projects. For startups, a decentralized proof market could greatly alleviate funding pressures during launch phases, while also reducing unfair competition driven by financial disparities.

Market Size: Paradigm predicted last year that the ZK miner/prover market might grow to match the historical size of PoW mining. The fundamental reason lies in the abundance of both buyers and sellers in the ZKP computing market. For former Ethereum miners, the numerous ZK-based public chains and Layer 2 projects offer far more appeal than ETH forked chains. Yet we must consider another scenario: most ZK chains or Layer 2s are fully capable of building their own proof-generation markets. Indeed, doing so aligns with decentralization narratives and is inevitable on their roadmaps (Starkware and zkSync plan decentralized versions too). So does a unified ZKP computing market still make sense?

Purpose of Construction: First, ZKP applications are extremely broad (we’ve cited many examples above, and will reference another project below). Second, even if each ZK chain maintains its own proof-generation market, a broader computing market still serves three purposes that motivate sellers to offer computing power:

1. Split computing power: allocate part for mining, part for selling compute contracts. This hedges against crypto market volatility. During downturns, sold compute contracts provide stable income; during upswings, self-mined portions yield extra profits;

2. Sell all computing power for fixed income—a more conservative strategy that reduces income fluctuation and ensures stability;

3. Some miners benefit from lower operational costs (e.g., cheaper electricity) than the market average. These miners can leverage their cost advantage by selling compute contracts at market prices, pocketing the margin created by lower power costs—achieving arbitrage.

Proof Market

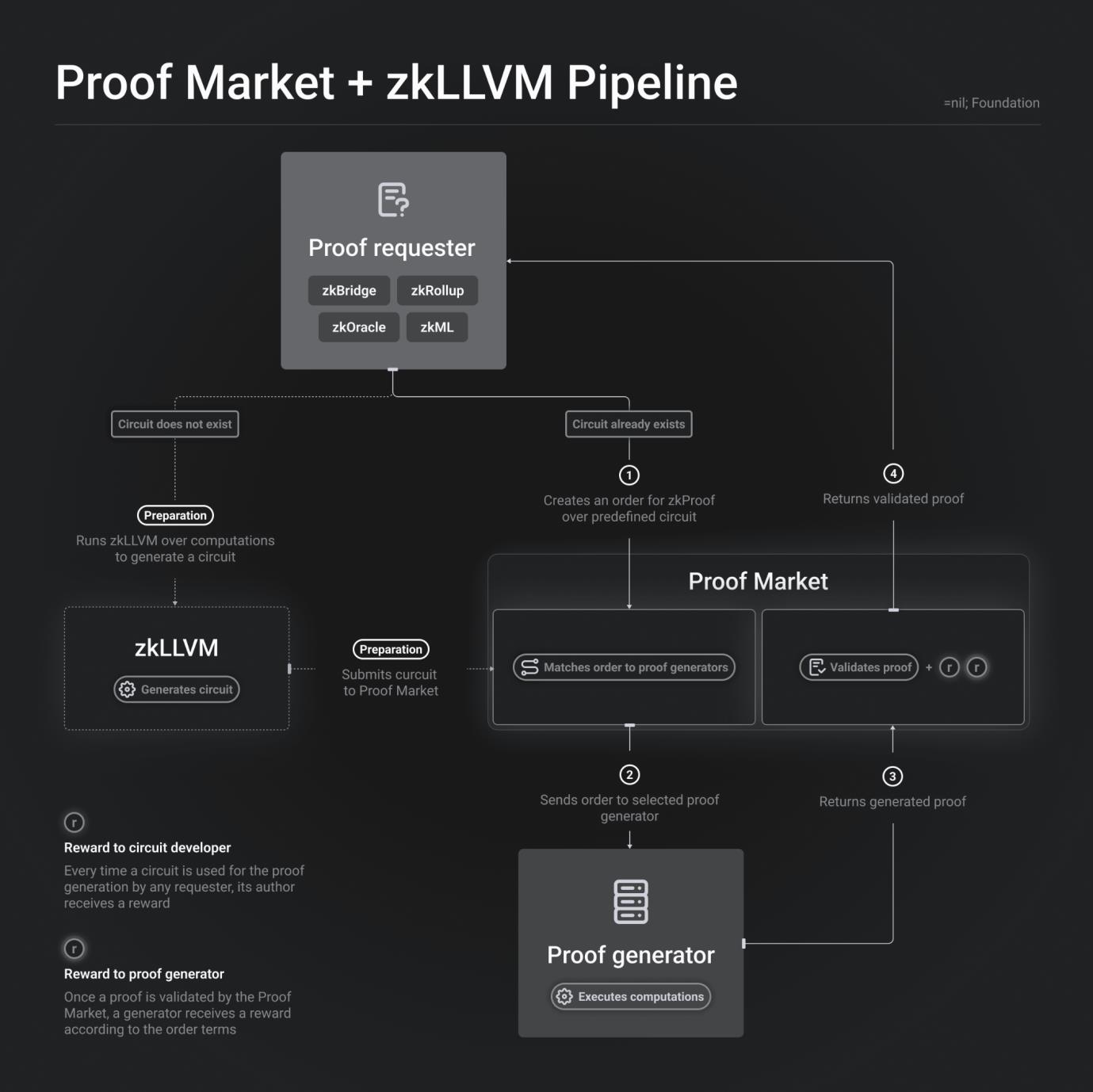

Proof Market is a decentralized ZKP computing marketplace built by =nil; (an Ethereum R&D company)—to my knowledge, the only existing marketplace focused on ZKP generation. At its core, it’s a trustless data availability protocol enabling Layer 1 and Layer 2 blockchains and protocols to generate zero-knowledge proofs seamlessly without relying on centralized intermediaries. Although Proof Market isn’t exactly the GPU-centric market I envisioned (it’s built around professional hardware providers; GPU-based ZKP mining can be seen in Scroll’s Roller Network or Aleo), it remains highly instructive regarding how to structure and widely deploy a ZKP computing market. The workflow of Proof Market is as follows:

Proof Requester:

-

An entity requesting a proof, such as applications like zkBridge, zkRollup, zkOracle, or zkML.

-

If no circuit exists, a Preparation phase is required, generating a new circuit via zkLLVM.

-

If a circuit already exists, create a zkProof request for the predefined circuit.

zkLLVM:

-

This component generates circuits—programs encoding computational tasks.

-

During preparation, zkLLVM preprocesses the computation to generate a circuit and submits it to Proof Market.

Proof Market:

-

A central marketplace matching proof requests with proof generators.

-

Verifies proof validity and disburses rewards once the proof is confirmed.

Proof Generator:

-

Performs the computation and generates the required zero-knowledge proof.

-

Receives orders from Proof Market and returns the generated proof.

Reward Mechanism:

-

Circuit Developer Reward: Whenever a proof requester uses a circuit to generate a proof, the circuit author receives a reward.

-

Proof Generator Reward: Once a proof is verified on Proof Market, the generator receives payment according to order terms.

Throughout the entire process, proof request, generation, verification, and reward distribution revolve around Proof Market. The goal is to create a decentralized, automated market where participants receive fair compensation based on their contributions.

Application Scenarios

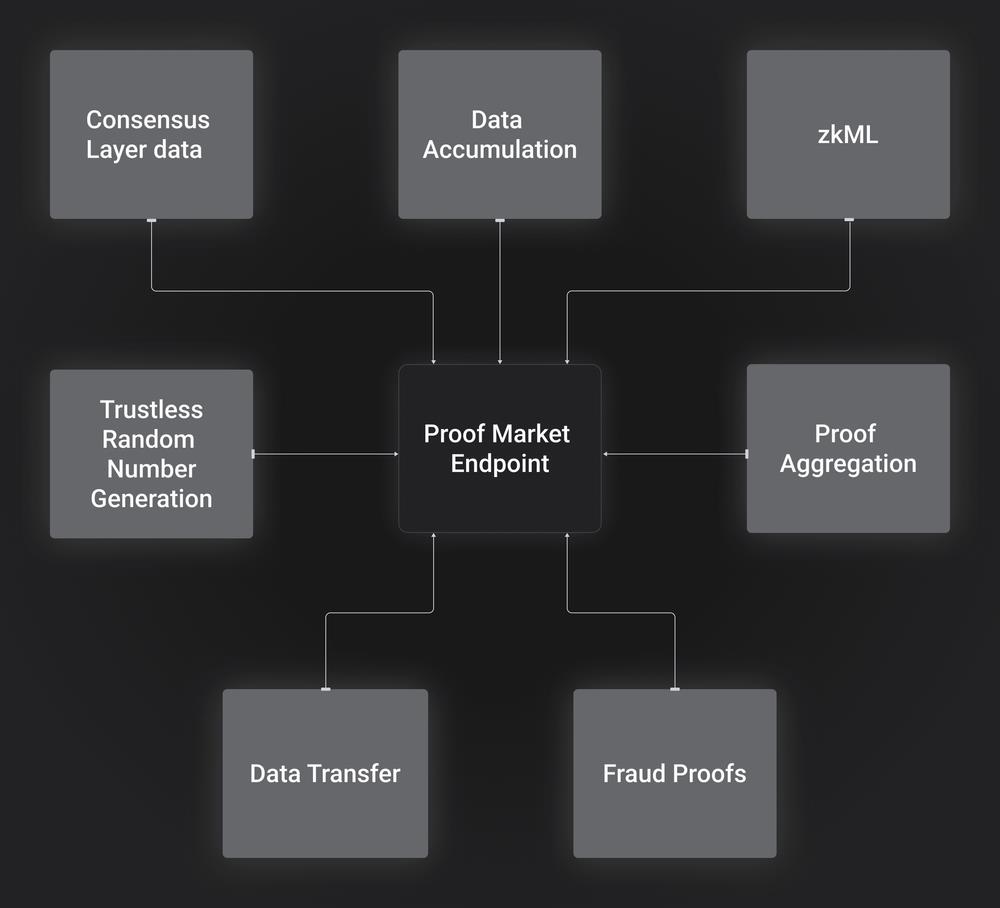

Since its test launch in January 2023, Proof Market’s primary use cases have been protocols operating outside Ethereum Layer 1—such as zkRollups, zkBridges connected to Ethereum, and public chains using ZKPs.

With integration of Ethereum endpoints (gateway interfaces allowing external systems to connect and integrate), Proof Market will support more applications—especially those needing direct proof requests from EVM apps for smoother UX or requiring on-chain data storage integration.

Below are some potential application scenarios:

-

Machine Learning (ML): Inference requests can be made to zkML applications on-chain. Fraud detection, predictive analytics, identity verification, and similar applications can be deployed on Ethereum.

-

Ethereum Data Processing (zkOracles): Many applications require historical or processed Ethereum data. With zkOracles, users can retrieve execution-layer data from the consensus layer.

-

Data Transfer (zkBridges): Users can directly request data transfers and pay proof fees without bridge operators acting as intermediaries between users and the market.

-

Fraud Proof: Some fraud proofs can be easily verified on-chain, others cannot. Fishermen (network participants focused on validating the main protocol and detecting potential fraud) can concentrate on verifying the main protocol and refer to required proofs provided by Proof Market.

-

Data Updates and Aggregation: Applications can store latest updates directly on Layer 1 and later aggregate them into a Merkle tree, attaching a proof of correct root update.

-

Random Number Generation: Applications can order random numbers generated via trustless hash-based VDFs.

-

Proof Aggregation: If applications submit proofs independently (without verification), aggregating them into a single proof and verifying it once can reduce overall verification costs.

Practical Example

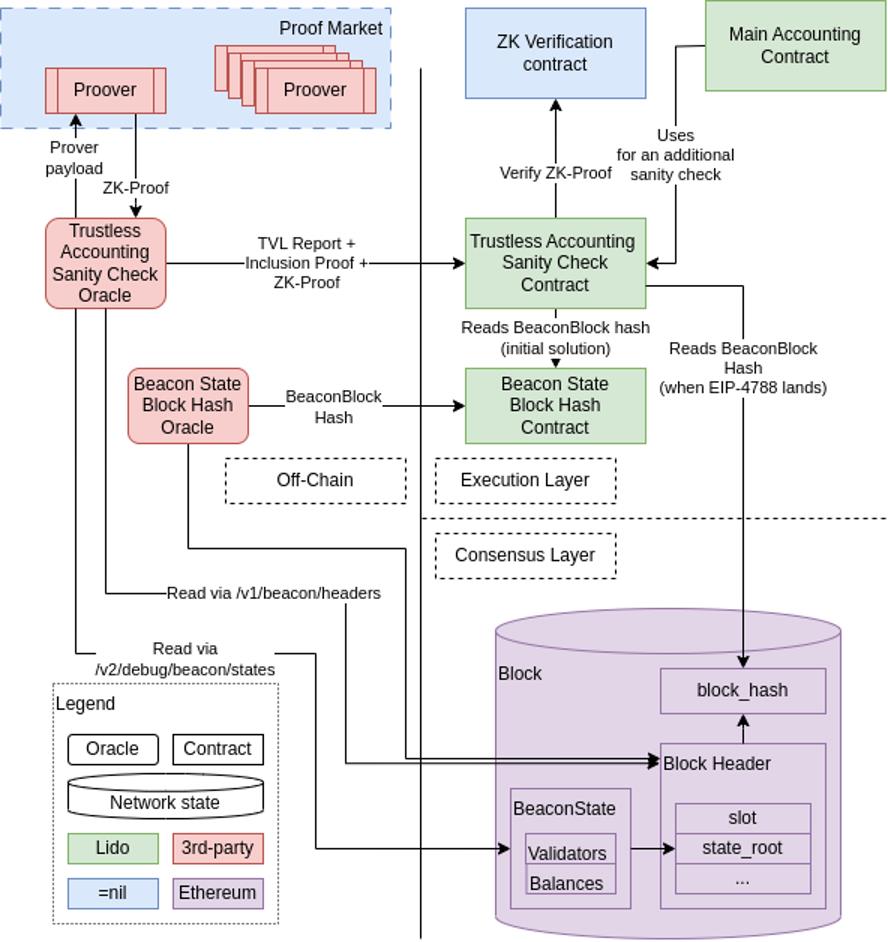

Recently, Lido—a well-known LSD project—is leveraging Proof Market to enhance the security and credibility of its Lido Accounting Oracle contract. Currently, the Lido Accounting Oracle relies on an oracle committee composed of trusted third parties and quorum mechanisms to maintain its state, creating potential attack vectors. Proof Market addresses this as follows:

Problem Definition

-

Lido Accounting Oracle Contract: Handles complex reports including consensus layer data (e.g., Total Value Locked (TVL), number of validators).

-

Objective: Make reporting trustless by extending reports to include computational validity proofs.

Solution Specification

-

Initial Goal: In phase one, report only subsets such as Lido CL balance (assets tied to the consensus layer in the Lido protocol), active balances, and exiting validator counts.

- Key Participants:

-

Lido: Needs certain consensus layer state data accessible on the execution layer.

-

Oracle: Reports TVL and validator count to the TVL contract.

-

Proof Producer: Generates computational integrity proofs.

-

Proof Verifier: Verifies proofs within the EL contract.

-

Technical Implementation

Oracle: Independent application that acquires input data, computes Oracle reports, and produces proofs.

zkLLVM Circuit: Program used to construct zero-knowledge proofs for computational integrity.

Trustless Accounting Audit Oracle Contract: Verifies binary proofs and validates computational integrity information.

Deployment Phases

-

Current State: When enough trusted Oracle members submit reports and reach quorum.

-

"Dark Launch" Phase: Quorum reached, but trustless reports are accepted and verified as needed.

-

Transition Phase: Trust quorum reached, at least one valid trustless report received, and reports are consistent.

-

Full Launch: Accounting contract uses only trustless reports to determine TVL and validator count.

-

Final State: Fully eliminate quorum-based reporting, relying solely on trustless reports.

Conclusion

Compared to the grand vision of the AGI computing market, the ZKP computing market is currently more confined to blockchain applications. Conversely, the advantage is that ZKP market development doesn’t need to contend with the extreme complexity of neural networks, resulting in lower overall development difficulty and reduced funding requirements. From the projects discussed above, it’s evident that while the AGI computing market struggles with practical implementation, the ZKP computing market is already permeating multiple blockchain application areas in a multidimensional manner.

From a market perspective, the ZKP computing market remains in a highly blue-ocean stage. Even Proof Market, mentioned above, falls short of my ideal design. Combining algorithmic optimization, application refinement, hardware improvements, and choices among different computing suppliers, the design space for ZKP computing markets remains vast. Looking ahead, Vitalik has repeatedly emphasized that ZK’s impact on the blockchain field over the next decade will be as transformative as blockchain itself. Yet considering ZK’s versatility, as designs mature, ZK’s significance beyond blockchain may rival today’s AGI—its prospects should not be underestimated.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News