Prospective High-Potential Sector: Decentralized Computing Power Market (Part 1)

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Prospective High-Potential Sector: Decentralized Computing Power Market (Part 1)

Will computing power shortages become inevitable, and could decentralized computing markets be a good business?

Author: Zeke, YBB Capital

Preface

Since the emergence of GPT-3, generative AI has triggered an explosive inflection point in the field of artificial intelligence due to its astonishing performance and broad application scenarios, prompting tech giants to flock into the AI赛道. However, problems have also arisen: training and inference of large language models (LLMs) require massive computing power, and as models iterate and upgrade, demand for computational resources and costs increase exponentially. For instance, GPT-2 and GPT-3 differ by a factor of 1166 in parameter count (GPT-2 has 150 million parameters, while GPT-3 has 175 billion), and the cost of a single training run for GPT-3 could reach up to $12 million at public GPU cloud prices—200 times that of GPT-2. In actual usage, each user query requires inference computation; based on 13 million unique users accessing the service early this year, approximately over 30,000 A100 GPUs would be required. The initial investment would thus amount to a staggering $800 million, with daily model inference costs estimated at $700,000.

Insufficient computing power and high costs have become major challenges across the entire AI industry. Yet similar issues may soon confront the blockchain sector. On one hand, Bitcoin’s fourth halving and potential ETF approval are approaching, and as prices rise in the future, miners will inevitably see surging demand for computing hardware. On the other hand, zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) technology is rapidly developing, with Vitalik repeatedly emphasizing that ZK will be as transformative to blockchain over the next decade as blockchain itself. While the industry holds high hopes for this technology, ZK proofs involve complex computations that, like AI, consume vast amounts of computing power and time during proof generation.

In the foreseeable future, computing power shortages will become inevitable. Could decentralized computing markets then become a promising business?

Definition of Decentralized Computing Markets

Decentralized computing markets are essentially equivalent to the decentralized cloud computing space, but personally, I find this term more fitting to describe upcoming projects discussed later. Decentralized computing markets fall under DePIN (Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks), aiming to create an open marketplace where token incentives allow anyone with idle computing resources to contribute them, primarily serving B2B users and developer communities. Well-known examples include Render Network—an Ethereum-based decentralized GPU rendering solution—and Akash Network—a distributed peer-to-peer cloud computing marketplace.

The following discussion begins with foundational concepts before delving into three emerging sub-sectors within this domain: AGI computing markets, Bitcoin mining markets, and ZK hardware acceleration markets—with focus here on AGI computing. The latter two will be covered in "Emerging Opportunities: Decentralized Computing Markets (Part 2)."

Overview of Computing Power

The concept of computing power dates back to the invention of computers, when early machines used mechanical components to perform calculations—their computational capacity referring to these mechanisms’ processing ability. As computer technology evolved, so did the notion of computing power. Today, it generally refers to the collaborative capability of computer hardware (CPUs, GPUs, FPGAs, etc.) and software (operating systems, compilers, applications, etc.).

Definition

Computing power refers to the volume of data or number of computational tasks a computer or other computing device can process within a given timeframe. It is commonly used to describe the performance of computing devices and serves as a key metric for evaluating their processing capabilities.

Measurement Standards

Computing power can be measured in various ways, including computation speed, energy consumption, precision, and parallelism. Common metrics in computing include FLOPS (floating-point operations per second), IPS (instructions per second), and TPS (transactions per second).

FLOPS measures a computer's ability to perform floating-point arithmetic—mathematical operations involving decimal numbers, which require consideration of precision and rounding errors. FLOPS is a standard indicator of high-performance computing, often used to evaluate supercomputers, high-end servers, and GPUs. For example, a system rated at 1 TFLOPS (one trillion floating-point operations per second) can execute one trillion such operations every second.

IPS indicates how quickly a computer executes instructions, measuring the number of instructions processed per second. This metric evaluates single-instruction performance, typically applied to CPUs. For instance, a CPU operating at 3 GHz processes 3 billion instructions per second.

TPS reflects a system’s transaction-handling capacity—the number of transactions completed per second—commonly used to assess database server performance. A database handling 1,000 TPS processes 1,000 database transactions each second.

Additionally, there are specialized metrics tailored to specific use cases, such as inference speed, image processing rate, and speech recognition accuracy.

Types of Computing Power

GPU computing power refers to the computational capability of Graphics Processing Units. Unlike CPUs, GPUs are specifically designed to handle graphics and video data, featuring numerous processing units and strong parallel computing abilities, enabling simultaneous execution of many floating-point operations. Originally developed for gaming graphics, GPUs usually offer higher clock speeds and greater memory bandwidth than CPUs to support complex graphical computations.

Differences Between CPU and GPU

-

Architecture: CPUs and GPUs differ fundamentally in design. CPUs typically feature one or multiple general-purpose cores capable of executing diverse operations. In contrast, GPUs contain thousands of stream processors and shaders optimized for graphics-related computations;

-

Parallel Computing: GPUs generally offer superior parallel processing capabilities. With limited core counts, CPUs execute one instruction per core, whereas GPUs possess thousands of stream processors capable of concurrent instruction execution. Hence, GPUs are better suited for highly parallel tasks such as machine learning and deep learning;

-

Programming: Programming GPUs is more complex than programming CPUs, requiring specialized languages like CUDA or OpenCL and specific techniques to leverage parallelism. By comparison, CPU programming is simpler using general-purpose tools and languages.

Importance of Computing Power

During the Industrial Revolution, oil was the lifeblood of the world, permeating every industry. In the coming AI era, computing power will serve as the world's “digital oil.” The significance is evident—from corporate frenzies over AI chips and Nvidia’s stock surpassing a $1 trillion valuation, to recent U.S. restrictions on advanced Chinese semiconductor exports down to specific thresholds of computing power and chip area—even contemplating bans on GPU cloud access. Computing power is poised to become the commodity of the next era.

Overview of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a technological science focused on researching, developing theories, methods, technologies, and application systems to simulate, extend, and enhance human intelligence. Originating in the 1950s–60s, AI has undergone over half a century of evolution through waves of symbolic, connectionist, and agent-based approaches. Today, as a transformative general-purpose technology, AI drives profound changes across industries and society. Current generative AI represents a step toward Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)—an AI system capable of broad understanding and performing intelligently across diverse tasks, matching or exceeding human-level cognition. AGI fundamentally relies on three pillars: deep learning (DL), big data, and large-scale computing power.

Deep Learning

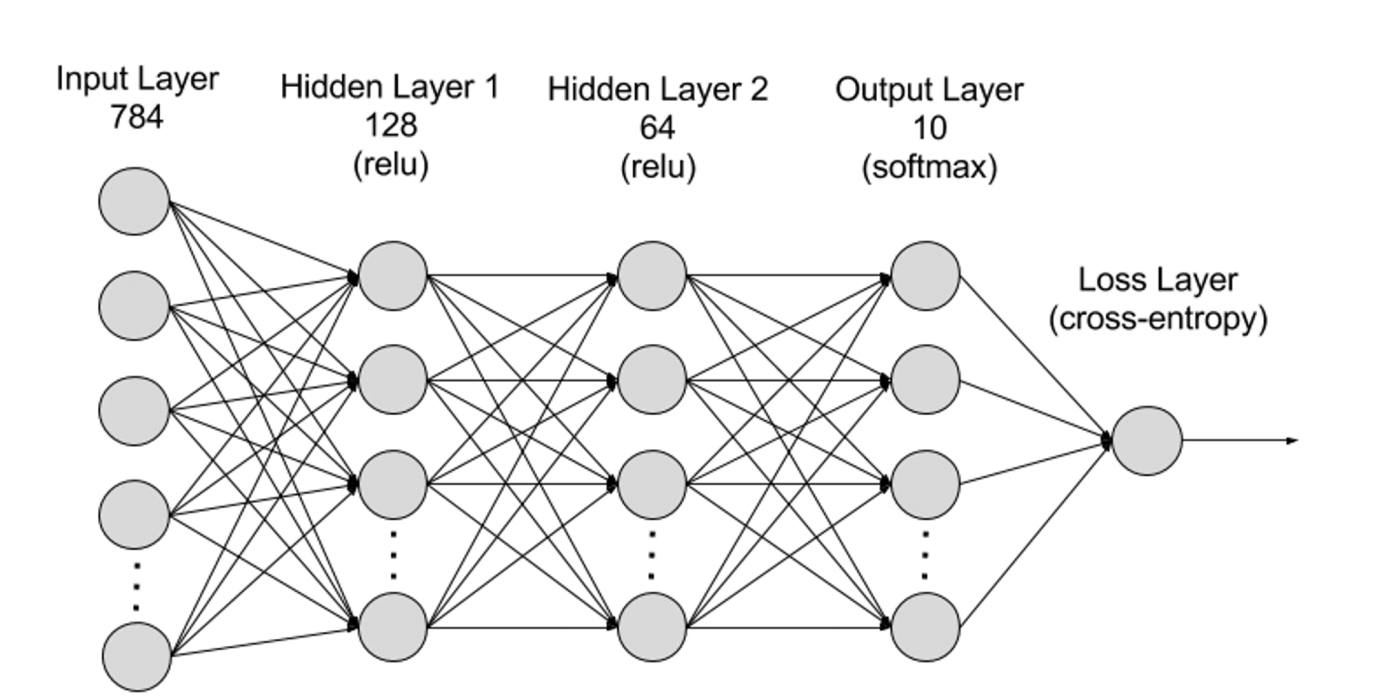

Deep learning is a subset of machine learning, utilizing algorithms modeled after the human brain's neural networks. Just as the brain contains millions of interconnected neurons working together to learn and process information, deep learning neural networks consist of multiple layers of artificial neurons operating collaboratively inside computers. These artificial neurons—software modules called nodes—use mathematical computations to process data. Deep learning algorithms employ such nodes to solve complex problems.

Neural networks are structured into input, hidden, and output layers, with connections between layers represented by parameters.

-

Input Layer: The first layer of a neural network, responsible for receiving external input data. Each neuron corresponds to a feature of the input. For example, in image processing, each neuron might represent a pixel value;

-

Hidden Layers: Process data from the input layer and pass it deeper into the network. Hidden layers analyze information at different levels, adjusting behavior upon receiving new inputs. Deep learning models may have hundreds of hidden layers, allowing multi-perspective analysis. For example, identifying an unknown animal involves comparing features like ear shape, leg count, and pupil size—similar to how hidden layers extract distinct characteristics for accurate classification;

-

Output Layer: The final layer producing the network’s output. Each neuron represents a possible category or value. In classification tasks, neurons correspond to classes; in regression, a single neuron outputs a predicted value;

-

Parameters: Connections between layers are defined by weights and biases, optimized during training to enable pattern recognition and prediction. Increasing parameters enhances model capacity—the ability to capture complex patterns—but also raises computing demands.

Big Data

Effective neural network training typically requires large volumes of diverse, high-quality, multi-source data. Big data forms the foundation for training and validating machine learning models. By analyzing these datasets, models learn underlying patterns and relationships to make predictions or classifications.

Large-Scale Computing Power

The multi-layered complexity of neural networks, vast parameter counts, big data requirements, iterative training processes (requiring repeated forward and backward propagation, activation functions, loss calculation, gradient computation, and weight updates), high-precision calculations, parallel computing needs, optimization techniques, and evaluation procedures collectively drive immense demand for computing power. As deep learning advances, AGI's requirement for large-scale computing increases roughly tenfold annually. The latest model, GPT-4, contains 1.8 trillion parameters, with a single training run costing over $60 million and requiring 2.15e25 FLOPS (21,500 trillion floating-point operations). Future models will continue expanding these demands.

AI Computing Economics

Future Market Size

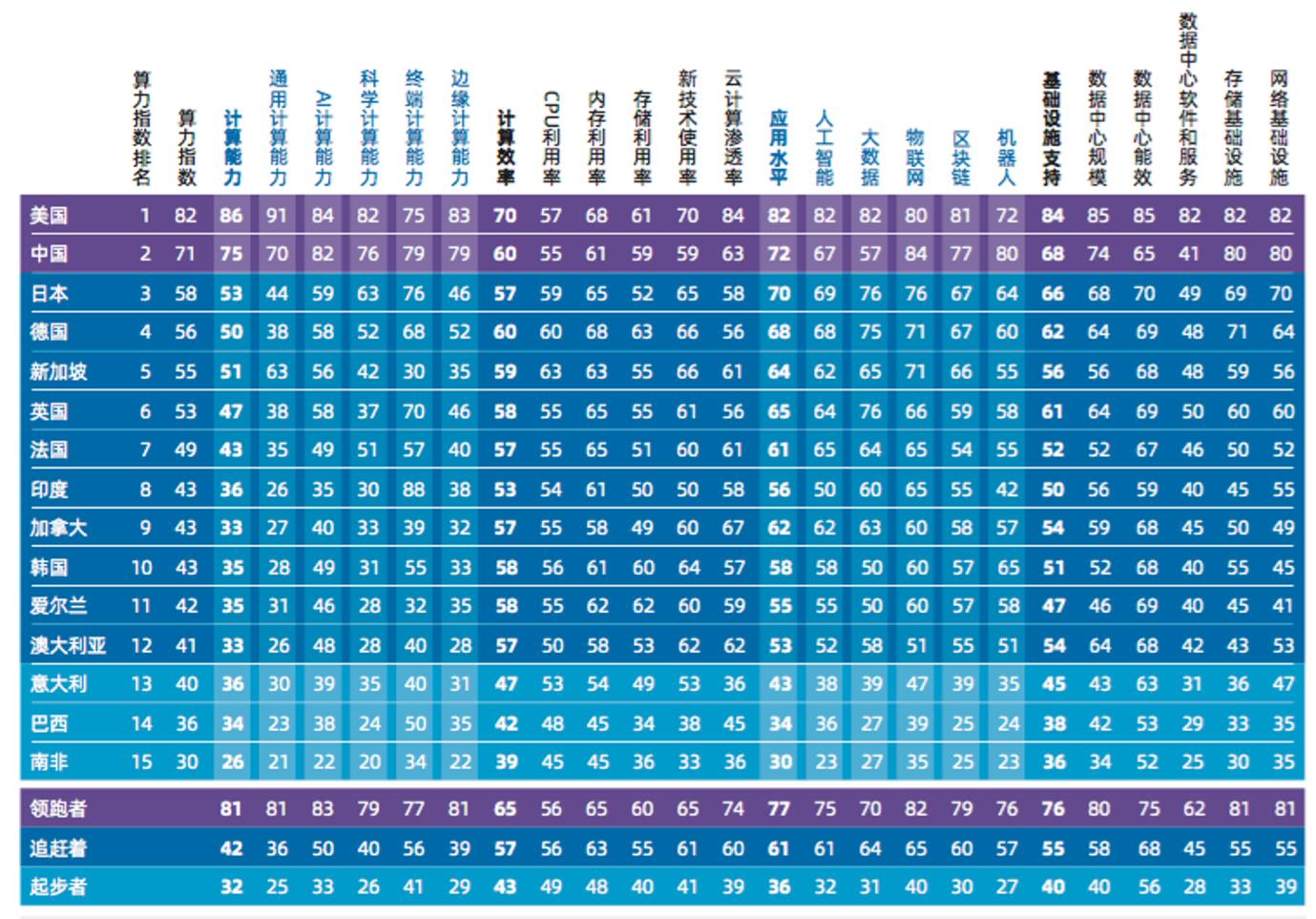

According to authoritative estimates from the International Data Corporation (IDC), in collaboration with Inspur Information and Tsinghua University’s Global Industry Institute, the global AI computing market will grow from $19.5 billion in 2022 to $34.66 billion in 2026. Specifically, the generative AI computing segment will expand from $820 million in 2022 to $10.99 billion in 2026, increasing its share of the overall AI computing market from 4.2% to 31.7%.

Monopolization of Computing Economics

AI GPU production is now monopolized by NVIDIA, with extreme pricing (the latest H100 GPU sells for up to $40,000 per unit). Upon release, these GPUs are immediately snapped up by Silicon Valley giants—some used internally for proprietary model training, others rented out via cloud platforms. Major providers like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft control massive server farms equipped with GPUs and TPUs. Computing power has become a newly monopolized resource, leaving many AI developers unable to purchase dedicated GPUs without markups. To access cutting-edge hardware, developers must rent from AWS or Microsoft Azure. Financial reports reveal extremely high profit margins—AWS Cloud Services achieves 61% gross margin, while Microsoft exceeds that at 72%.

Must we accept this centralized authority and pay 72% profit premiums? Will Web2 giants dominate the next era too?

Challenges of Decentralized AGI Computing

When discussing anti-monopoly solutions, decentralization is often seen as ideal. Can existing projects—such as DePIN storage combined with idle GPU protocols like RDNR—meet the massive computing demands of AI? The answer is no. The path to disruption isn’t simple—early projects weren't designed for AGI workloads and lack feasibility. Bringing computing power on-chain faces at least five key challenges:

1. Work Verification: Building a truly trustless computing network requires mechanisms to verify whether deep learning computations were actually performed. The core issue lies in the state dependency of deep learning models—each layer's input depends on the previous layer’s output. Thus, verifying a specific layer necessitates re-executing all prior layers, making partial verification insufficient;

2. Market Dynamics: The AI computing market, being nascent, suffers from supply-demand imbalances and cold-start problems. Supply and demand liquidity must align from inception for sustainable growth. Providers need clear incentives for contributing resources. Traditional intermediaries manage operations and minimize overhead via minimum payout thresholds, but scaling remains costly. Only a fraction of available supply becomes economically viable, creating a threshold equilibrium limiting further expansion;

3. The Halting Problem: A fundamental challenge in computation theory, it concerns determining whether a given task will terminate in finite time or run indefinitely. This problem is undecidable—no universal algorithm can predict termination for all programs. Ethereum smart contracts face similar uncertainty regarding execution duration and resource needs;

(In deep learning, this is exacerbated as models shift from static to dynamic graph construction and execution.)

4. Privacy: Privacy-aware design is essential. While much ML research uses public datasets, fine-tuning models on proprietary user data improves performance and applicability. Such processes may involve personal data, necessitating robust privacy safeguards;

5. Parallelization: This is the critical barrier to current project viability. Deep learning models are trained in parallel on large, tightly integrated hardware clusters with ultra-low latency. In distributed networks, frequent inter-GPU communication introduces delays and bottlenecks due to the weakest-performing GPU. Achieving efficient heterogeneous parallelization under untrusted and unreliable conditions remains unsolved. Promising approaches include transformer-based models like Switch Transformers, already exhibiting high degrees of parallelizability.

Solutions: Although attempts at decentralized AGI computing markets remain in early stages, two projects—Gensyn and Together—have begun addressing consensus design and practical deployment of decentralized computing for model training and inference. Below, we analyze their architectural designs and limitations.

Gensyn

Gensyn is an AGI computing marketplace currently under development, aiming to tackle multiple challenges in decentralized deep learning and reduce current costs. Fundamentally, Gensyn is a Proof-of-Stake Layer 1 protocol built on Polkadot, rewarding Solvers directly via smart contracts for contributing idle GPU resources to execute machine learning tasks.

Returning to the earlier challenge: building a truly trustless computing network hinges on verifying completed machine learning work—a highly complex problem requiring balance among complexity theory, game theory, cryptography, and optimization.

Gensyn proposes a simple approach: solvers submit results of completed ML tasks. To verify accuracy, independent verifiers re-execute the same work—a method known as single replication, entailing only one additional verification effort. However, if the verifier isn’t the original requester, trust issues persist—verifiers themselves may be dishonest and require verification, potentially triggering an infinite chain of verifications. To break this cycle, three key concepts are introduced and woven into a four-role participant system.

Proof of Learning: Uses metadata from gradient-based optimization to generate certificates proving work completion. Certain stages can be replicated to quickly validate these certificates.

Graph-Based Pinpointing Protocol: Employs a multi-granularity, graph-based precise localization protocol with cross-verifier consistency checks. Allows rerunning and comparing verification steps for consistency, ultimately confirmed by the blockchain.

Truebit-Style Incentive Game: Uses staking and slashing mechanisms to ensure economically rational participants act honestly and fulfill assigned tasks.

The participant system consists of Submitters, Solvers, Verifiers, and Whistleblowers.

Submitters: End-users who submit tasks for computation and pay for completed work units;

Solvers: Primary workers executing model training and generating proofs checked by verifiers;

Verifiers: Bridge non-deterministic training with deterministic linear computation by replicating part of the solver’s proof and comparing distances against expected thresholds;

Whistleblowers: Serve as the final defense line, auditing verifiers’ work and issuing challenges for substantial rewards.

System Operation

The protocol’s game-theoretic system comprises eight phases involving four main roles, covering the full lifecycle from task submission to final validation.

-

Task Submission: Tasks consist of three elements:

- Metadata describing the task and hyperparameters;

- A model binary (or base architecture);

- Publicly accessible, preprocessed training data.

-

To submit a task, the submitter specifies details in machine-readable format along with the model binary and location of preprocessed data, uploading everything to-chain. Public data can reside in centralized object storage (e.g., AWS S3) or decentralized alternatives (IPFS, Arweave, Subspace).

-

Profiling: Establishes a baseline distance threshold for proof validation. Verifiers periodically fetch profiling tasks and generate variance thresholds by deterministically rerunning parts of the training with different random seeds, establishing expected deviation ranges for non-deterministic workflows.

-

Training: After profiling, tasks enter a public pool (akin to Ethereum’s mempool). A solver is selected, removes the task, and executes it using provided metadata, model, and data. During training, the solver generates proof-of-learning via periodic checkpoints storing intermediate metadata (including parameters) for verifiers to accurately replicate subsequent optimization steps.

-

Proof Generation: Solvers periodically store model weights/updates and corresponding dataset indices identifying samples used. Checkpoint frequency can be adjusted for stronger guarantees or reduced storage. Proofs can be “stacked”—starting from random initialization or pretrained weights with existing proofs—enabling creation of verified foundation models for downstream fine-tuning.

-

Proof Verification: Upon completion, the solver registers task completion on-chain and publishes the proof publicly. Verifiers pull verification tasks, recompute portions of the proof, calculate distances, and compare against thresholds computed during profiling. The chain determines match validity.

-

Graph-Based Pinpoint Challenge: After proof verification, whistleblowers can replicate the verifier’s work to detect errors (malicious or otherwise) and initiate on-chain arbitration challenges for rewards. Rewards come from deposits (in true positives) or lottery pools (in false positives), with the chain acting as arbiter.

Whistleblowers (in their role as verifiers) participate only when expecting adequate compensation, influenced by real-time participation levels. Their default strategy is to join when few others are active, stake, randomly select a task, begin verification, then continuously pick new ones until participation exceeds their payoff threshold—then exit (or switch roles based on hardware capability), rejoining when conditions reverse. -

Contract Arbitration: When challenged, verifiers engage the chain in a dispute-resolution process to pinpoint contested operations or inputs, with the chain executing final atomic operations to determine legitimacy. Periodic forced faults and jackpot payouts maintain whistleblower honesty and resolve verifier dilemmas.

-

Settlement: Participants are paid based on probabilistic and deterministic verification outcomes. If work passes all checks, solvers and verifiers receive rewards according to executed actions.

Project Assessment

Gensyn has crafted an elegant game-theoretic system at the verification and incentive layers, enabling rapid identification of discrepancies. However, many implementation details remain unclear—for example, how to set parameters ensuring fair rewards without excessive barriers. Are edge cases and varying solver capabilities adequately considered? The current whitepaper lacks detailed explanations of heterogeneous parallel execution. Overall, Gensyn still faces a long road to realization.

Together.ai

Together is a company focused on open-sourcing large models and advancing decentralized AI computing solutions, aiming to make AI accessible to anyone, anywhere. Strictly speaking, Together is not a blockchain project, but it has made preliminary progress in solving latency issues inherent in decentralized AGI computing networks. Therefore, the following analysis focuses solely on Together’s technical approach, without project evaluation.

How can large model training and inference be achieved when decentralized networks are 100x slower than data centers?

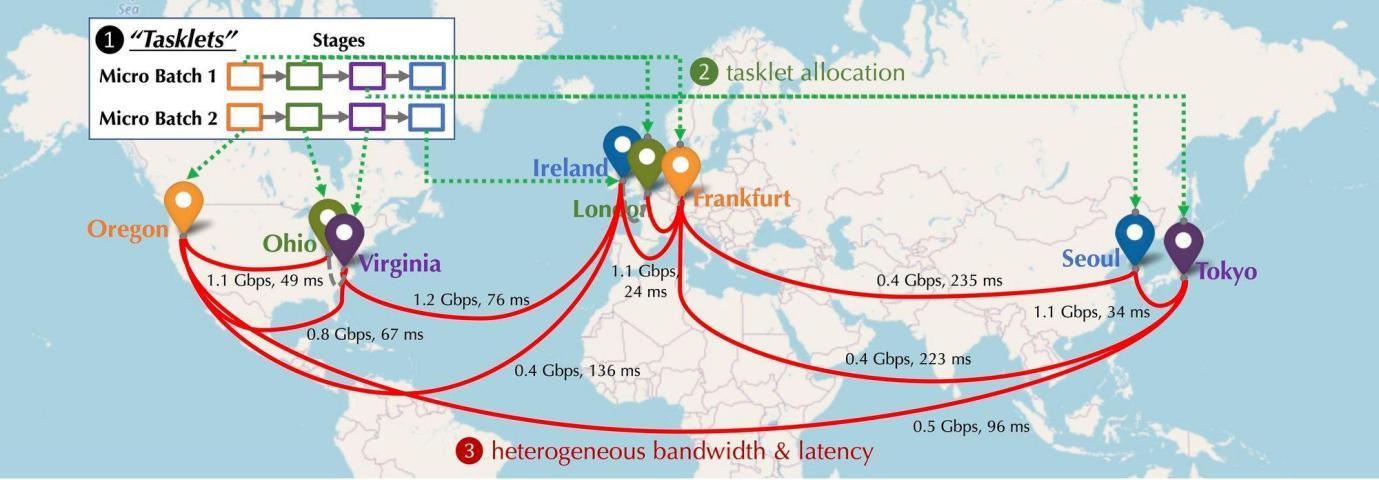

Imagine the distribution of GPUs participating in a decentralized network—spread across continents, cities, connected via links with varying latency and bandwidth. As shown below, simulating a distributed setup with devices in North America, Europe, and Asia reveals vastly different connectivity profiles. How can such disparate devices be effectively coordinated?

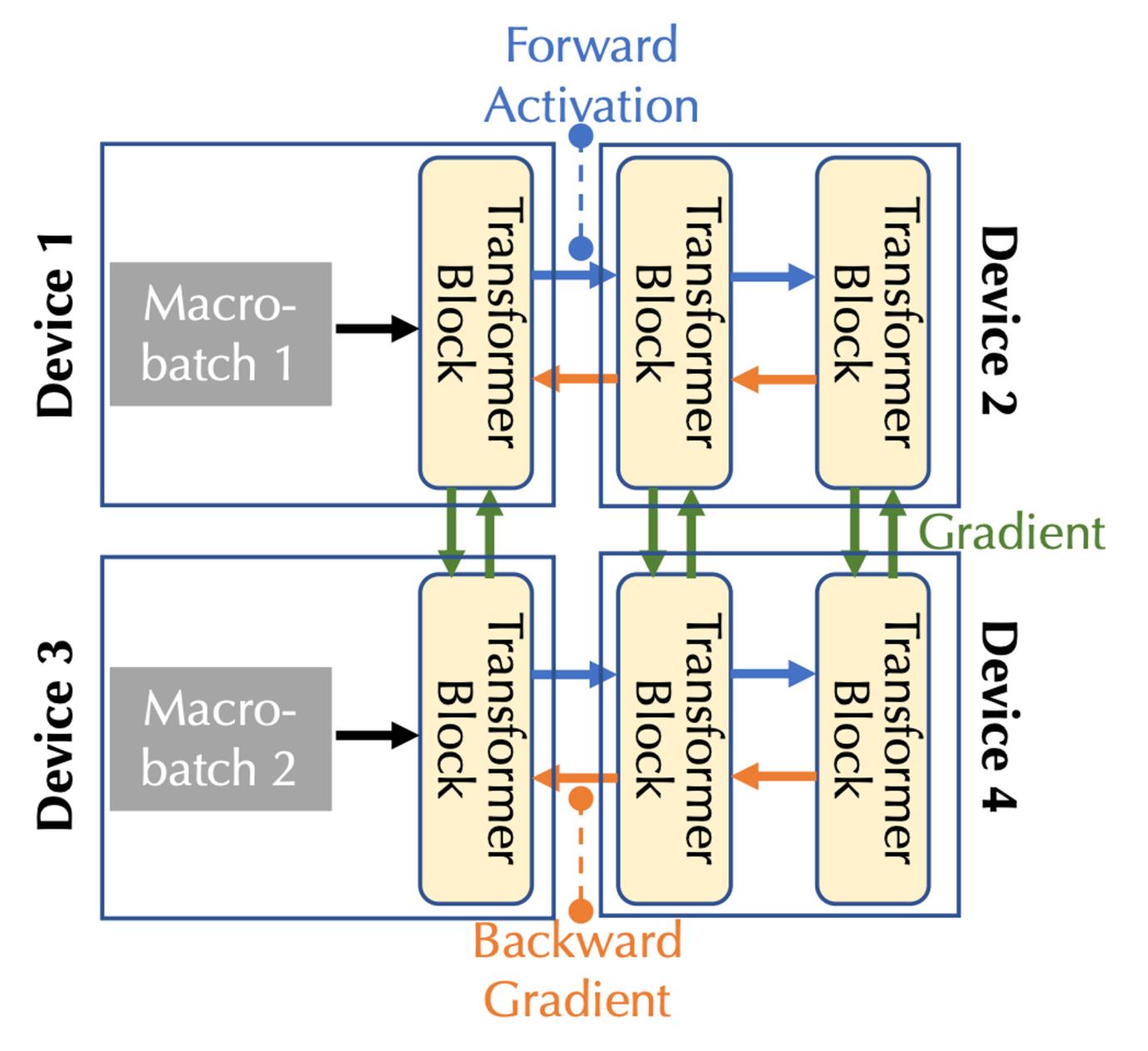

Distributed Training Computation Modeling: The diagram below illustrates base model training across multiple devices, showing three types of communication: forward activation, backward gradient, and lateral communication.

Considering both bandwidth and latency, two forms of parallelism must be addressed: pipeline parallelism and data parallelism, corresponding to the three communication types above:

-

In pipeline parallelism, model layers are divided into stages, each handled by a device. During forward pass, activations propagate forward; during backward pass, gradients flow backward;

-

In data parallelism, devices independently compute gradients on different microbatches but must synchronize them via communication.

Scheduling Optimization:

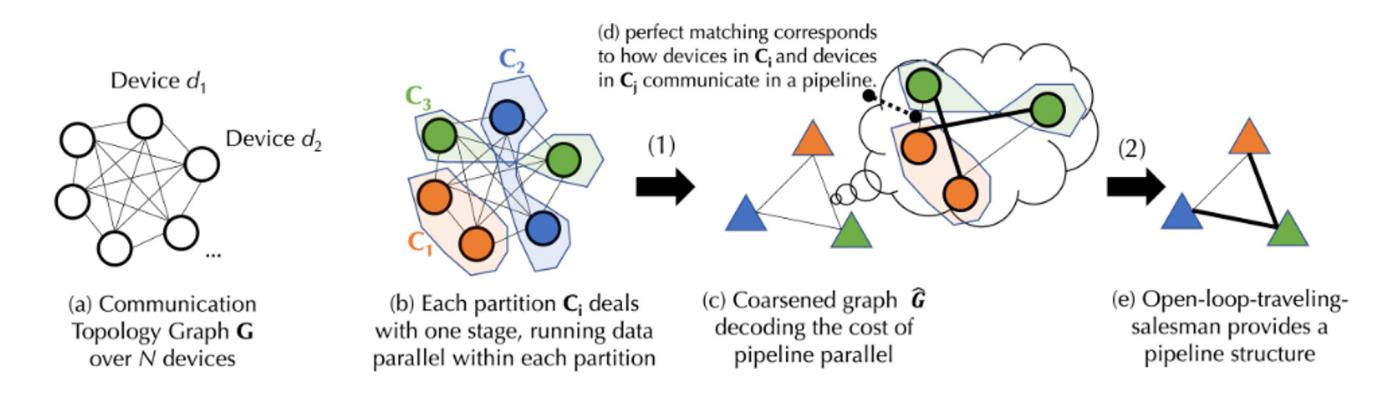

In decentralized environments, training is often communication-bound. Scheduling algorithms assign heavily communicating tasks to faster-connected devices. Considering task dependencies and network heterogeneity, Together introduces a novel formula to model scheduling costs, decomposing the cost model into two layers using graph theory:

-

Graph theory, a branch of mathematics studying graphs (networks) composed of vertices and edges, helps understand connectivity, coloring, paths, and cycles;

-

The first layer addresses balanced graph partitioning—dividing vertices into equally sized subsets while minimizing inter-subset edges—to reduce data-parallel communication costs;

The second layer combines joint graph matching and traveling salesman problems—a combinatorial optimization combining element matching and shortest-path traversal—to minimize pipeline-parallel communication costs.

Above is a schematic workflow. Due to complex underlying formulas, the following explanation simplifies the process for clarity. Detailed implementations are available in Together’s official documentation.

Assume a device set D of N devices with variable communication latency (matrix A) and bandwidth (matrix B). From D, generate a balanced graph partition—each group containing roughly equal devices processing the same pipeline stage—ensuring similar workload distribution in data parallelism. Based on latency and bandwidth, compute the “cost” of inter-group data transfer. Merge each balanced group into a fully connected coarse graph, where nodes represent pipeline stages and edges denote communication costs. Use matching algorithms to determine optimal collaborating groups.

Further optimization treats this as an open-loop Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)—finding the optimal data transmission path without returning to start. Finally, Together applies its innovative scheduling algorithm to find the best allocation strategy under the cost model, minimizing communication overhead and maximizing training throughput. Real-world tests show that even with 100x slower networks, end-to-end training throughput slows only 1.7–2.3x.

Communication Compression Optimization:

For communication compression, Together introduces AQ-SGD (see paper: Fine-tuning Language Models over Slow Networks using Activation Compression with Guarantees), a novel activation compression technique targeting communication efficiency in low-speed pipelined parallel training. Unlike direct activation compression, AQ-SGD compresses changes in activation values across training iterations, introducing a self-improving dynamic that enhances performance as training stabilizes. Rigorous theoretical analysis proves good convergence rates under bounded quantization error. Despite increased memory and SSD usage for storing activations, AQ-SGD adds no end-to-end runtime overhead. Extensive experiments demonstrate effective compression to 2–4 bits without sacrificing convergence. Moreover, AQ-SGD integrates with state-of-the-art gradient compression for “end-to-end communication compression,” reducing precision across all inter-machine exchanges—including gradients, forward activations, and backward gradients—greatly improving distributed training efficiency. Compared to uncompressed centralized networks (e.g., 10 Gbps), performance drops only 31%. Combined with scheduling optimizations, although still lagging behind centralized counterparts, the gap is narrowing, offering strong future potential.

Conclusion

During the AI boom, the AGI computing market stands out as the most promising and highest-demand segment among all computing markets. Yet, it also presents the greatest challenges in terms of development difficulty, hardware requirements, and capital needs. Based on the two projects analyzed, we remain some distance from realizing a functional AGI computing market. True decentralized networks prove far more complex than idealized visions and are clearly not yet competitive with cloud giants.

While writing this article, I’ve noticed small, early-stage (PPT-phase) projects exploring alternative entry points—focusing on lower-hanging fruit like inference or small-model training. These are valuable experiments. In the long term, decentralization and permissionless access matter deeply. The right to access and train AGI should not concentrate in the hands of a few centralized gatekeepers. Humanity doesn’t need a new “religion” or “pope,” nor should it pay exorbitant dues.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News