The Computation of Institutions

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Computation of Institutions

Democracy is essentially a distributed computer.

Author: Zhou Hang

This article unavoidably mixes Chinese and English to circumvent certain issues—an无奈 linguistic corruption, if you will.

Having spent a long time in tech circles, no one can avoid Moore's Law. The saying goes: the number of transistors on a chip doubles every eighteen to twenty-four months, and computing power takes another leap forward. Don't underestimate this empirical formula—it has shaped the world over the past fifty years. Computers have become faster, phones smarter, and AI can even write articles, all thanks to Moore's Law.

Sometimes I wonder: does society have a similar law? Not about transistors, but about us humans. How we organize ourselves, make decisions, handle complex problems—is there a kind of "computing power" that upgrades over time? The more I think about it, the more convinced I become: that thing is Democracy.

Democracy isn't just empty rhetoric; it's a mechanism, a machine. It aggregates millions of people's information and judgments, then computes an outcome. It’s slow, noisy, chaotic—but it is society’s "supercomputer."

Democracy is essentially a distributed computer

Think of it this way: when a person votes, speaks, or expresses an opinion, it's like a CPU executing an instruction. A single instruction means little, but when millions or tens of millions are combined, society completes a massive computation.

Autocracy resembles a standalone computer. All decisions are centralized on one CPU. Reactions are fast—building highways or launching projects requires only a few nods. Superficially efficient, but once that CPU crashes, the entire State bluescreens. We've seen too many such stories in history.

Democracy is a distributed system. It has many nodes, high latency, and constant arguments, yet the system rarely collapses. If one part fails, others can compensate. The more complex society becomes, the more it needs this distributed architecture.

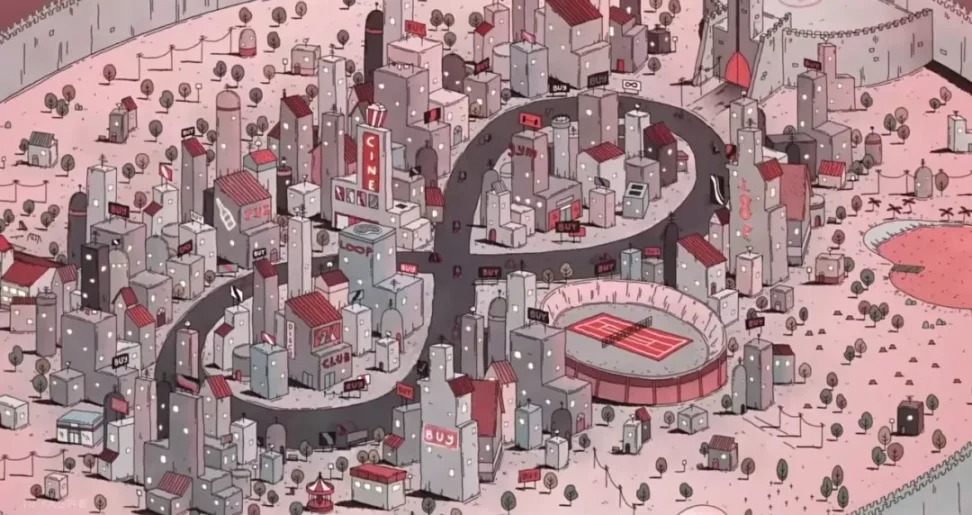

Take a recent example: Polymarket. It's a prediction market platform where users buy shares labeled "yes" or "no" to bet on whether an event will happen—like "Will the US enter recession in 2025?" The share price reflects the collective probability estimate. As new information emerges, prices adjust instantly—the market continuously corrects itself.

This is like a small-scale distributed computer: individuals with different information place bets, and the final market price becomes a synthesized result. It's not perfect, but often more reliable than expert forecasts.

Win probability trends for Trump, Biden, and Harris on Polymarket during the 2024 US election, accurately predicting the outcome

This is the "computing power of Democracy": not relying on a few geniuses guessing, but on countless ordinary people constantly inputting and correcting, synthesizing a judgment closer to reality.

This machine certainly has its flaws

Some might say: then why do we often see Democracy societies in chaos? Parliaments erupt in shouting matches, governments shut down, elections turn into dog-eat-dog battles—how is this like a "supercomputer"?

In fact, this is like seeing a distributed computer's log output for the first time—full of errors, delays, and conflicts. To laypeople it looks messy; experts know this is normal operation. The advantage of distributed systems isn't the absence of problems, but the ability to keep running despite them.

That said, this "Democracy computer" does have its bottlenecks:

-

Information noise: everyone can speak, so misinformation and junk content flood the space, lowering signal-to-noise ratio.

-

Polarization: nodes stop communicating and start attacking each other, wasting computing power on internal friction.

-

Short-termism: driven by elections, everyone chases immediate gains while long-term issues go unaddressed.

-

Asymmetry: some have access to vast data, others only consume gossip news—huge disparities in input quality.

The problem therefore isn't that "Democracy doesn't work," but how to better utilize its computing power. To improve quality, we must upgrade the algorithm—faster fact-checking, smoother communication channels, more rational incentive structures.

With AI arriving, we must decide how this machine keeps playing

Now comes the crucial question: will AI accelerate Democracy's computing power, or replace it entirely?

If AI is used to help filter information, predict policy outcomes, and provide multi-angle analysis, then it becomes an accelerator for Democracy. The Democracy machine was already noisy and chaotic—now it gains a smart assistant to clear out much of the noise.

But if AI is controlled by a few, it becomes dangerous. It could turn into a super standalone machine, siphoning away computing power and creating a new Autocracy that appears efficient but lacks error correction.

So the future doesn't hinge on whether AI can surpass Democracy, but whether we can integrate AI into Democracy. Open-source, transparent, decentralized—ensuring diverse groups can access it, rather than letting a few institutions monopolize it.

In the end, Democracy's computing power isn't perfect. It's slow, messy, and often disappointing. But it has one irreplaceable trait: fault tolerance. It allows mistakes, enables correction, and permits coexistence of diversity. In a complex world, fault tolerance matters more than speed.

Whoever can effectively aggregate more people's judgments will go further. Moore's Law may have limits, but as long as human society keeps growing in complexity, Democracy's computing power will always have room to rise.

All images in this article|Loop. This is an animated short film directed by Argentine filmmaker Pablo Polledri. Using abstract and repetitive visual language, it portrays a mechanized, institutionalized society: people function like gears, repeating the same behaviors day after day—until broken by "love"...

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News