Beyond the Rollup Wave, VMs Still Have Stories to Tell

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Beyond the Rollup Wave, VMs Still Have Stories to Tell

Ethereum's vast user ecosystem means that any blockchain network abandoning it will struggle to compete in the short term.

Author: PSE Trading Analyst @cryptohawk

TL;DR

1. A virtual machine (VM) is a software-emulated computer system that provides an execution environment for programs. It can simulate various hardware components, enabling programs to run in a controlled and compatible environment.

2. The Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) is a stack-based VM used to execute Ethereum smart contracts. zkEVM optimizes zk-proof generation efficiency while maintaining EVM equivalence or compatibility. In contrast, zkVM abandons EVM compatibility in favor of prioritizing zk-friendliness. Privacy zkVM adds native privacy features on top of zkVM. SVM, FuelVM, and MoveVM all pursue peak performance through parallel execution but differ in design specifics. ESC VM and BitVM conduct innovative computational layer experiments on ETH and BTC blockchains respectively, though real-world demand remains low under current conditions.

3. The massive user ecosystem built around EVM means any blockchain abandoning it will struggle to compete in the short term. Therefore, non-EVM ecosystems must adopt tools like transpilers, compilers, bytecode interpreters, or VM compatibility layers to attract EVM users and leverage their unique VM capabilities to build compelling new narratives—a likely prerequisite for success.

1.1 What is a VM?

A virtual machine (VM) is a foundational component of virtualized computing resources, offering nearly all the functionalities of a physical computer, including running applications and operating systems. The concept of VMs is not new and has been widely adopted across numerous technology ecosystems.

In the context of blockchain, a VM is software that runs programs—commonly referred to as the runtime environment for executing blockchain smart contracts. A VM typically provides a virtual computing environment by simulating different hardware devices. While simulated hardware varies across VMs, common components include CPU, memory, disk storage, and network interfaces. When a transaction is submitted on-chain, the VM processes it and updates the blockchain state—the global state of the entire network—affected by the transaction. The specific rules governing state changes are defined by the VM. During transaction processing, the VM converts smart contract code into a format executable by nodes/validators.

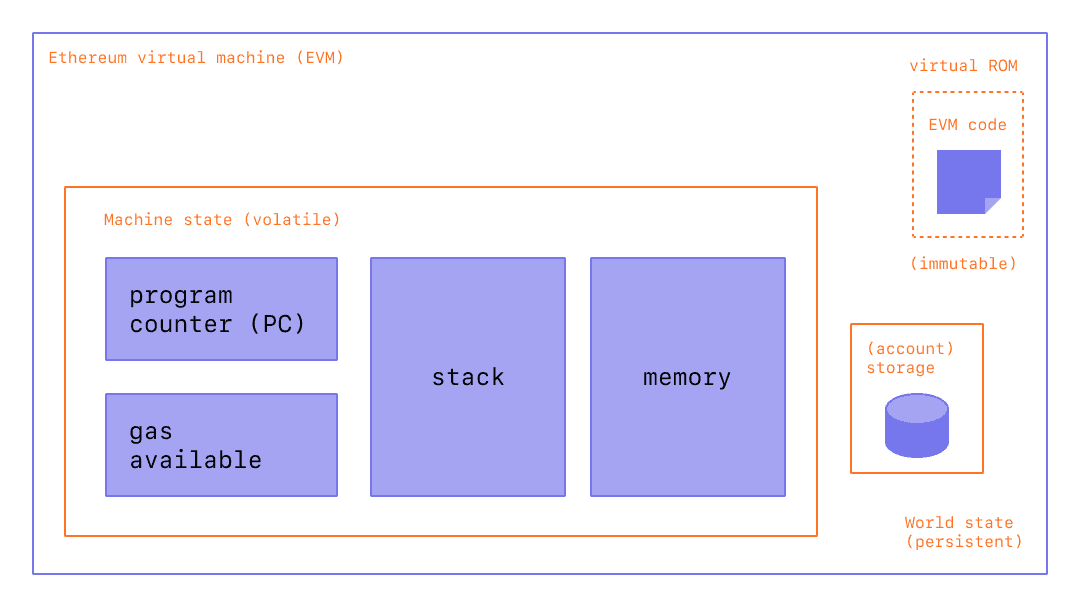

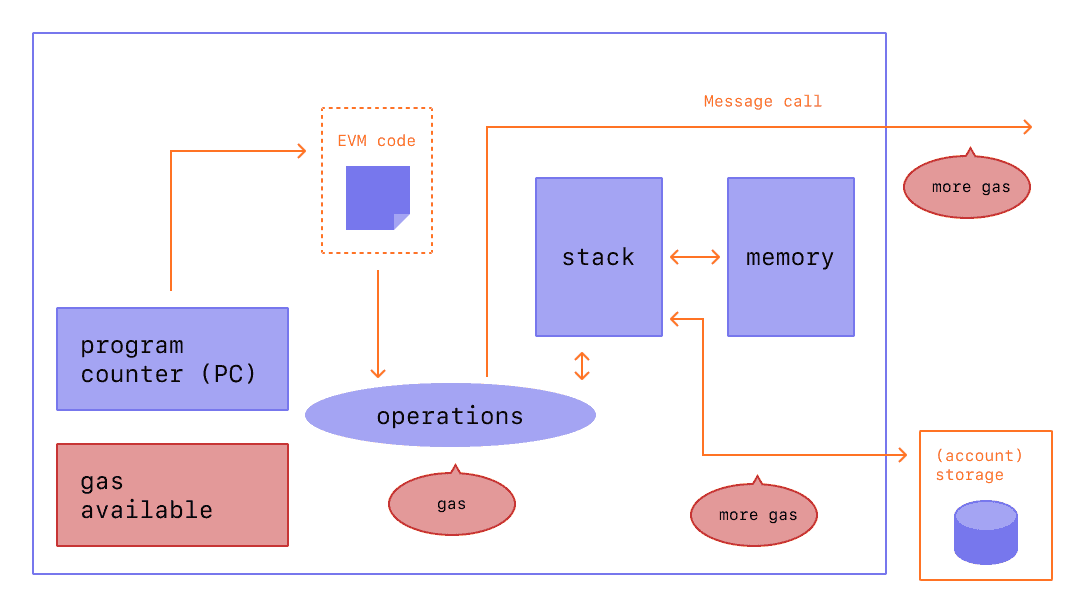

The most critical kernel within a VM is LLVM (low-level virtual machine), which serves as the core of compilers. The diagram below illustrates the original EVM workflow: smart contracts are transformed via LLVM IR (Intermediate Representation) into bytecode. This bytecode is stored on the blockchain. When a smart contract is invoked, the bytecode is converted into corresponding opcodes and then executed by the EVM and node hardware.

1.2 Mainstream VMs

1.2.1 EVM — "One Stone Rules Them All: EVM Takes Eight Dou, Others Share Two Dou"

Representative Projects: Optimism, Arbitrum

As the most active blockchain ecosystem in terms of developers and users today, the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) is a stack-based virtual machine that simulates hardware such as CPU, memory, storage, and stack to provide a virtual computing environment for executing smart contract instructions and storing their states and data. The EVM instruction set includes various opcodes—for example, arithmetic operations, logical operations, storage operations, and jump operations.

The memory and storage simulated by the EVM are used to store the state and data of smart contracts. The EVM treats memory and storage as two distinct regions, accessing contract state and data through read and write operations.

The stack simulated by the EVM stores operands and results of instructions. Most instructions in the EVM instruction set are stack-based—they pop operands from the stack, perform operations, and push results back onto the stack.

The design process of the EVM was clearly bottom-up: first defining the simulated hardware environment (stack, memory), then designing its own assembly instruction set (opcodes) and bytecode accordingly. To improve EVM execution efficiency, the Ethereum community developed two compiled high-level languages: Solidity and Vyper. Solidity needs no introduction; Vyper was designed by Vitalik to address certain flaws in Solidity but failed to gain significant adoption and gradually faded from prominence.

1.2.2 zkEVM — "I Want It All": EVM Compatibility + Support for zk-Proof Generation on Global State Transitions

Representative Projects: Taiko, Scroll, Polygon zkEVM

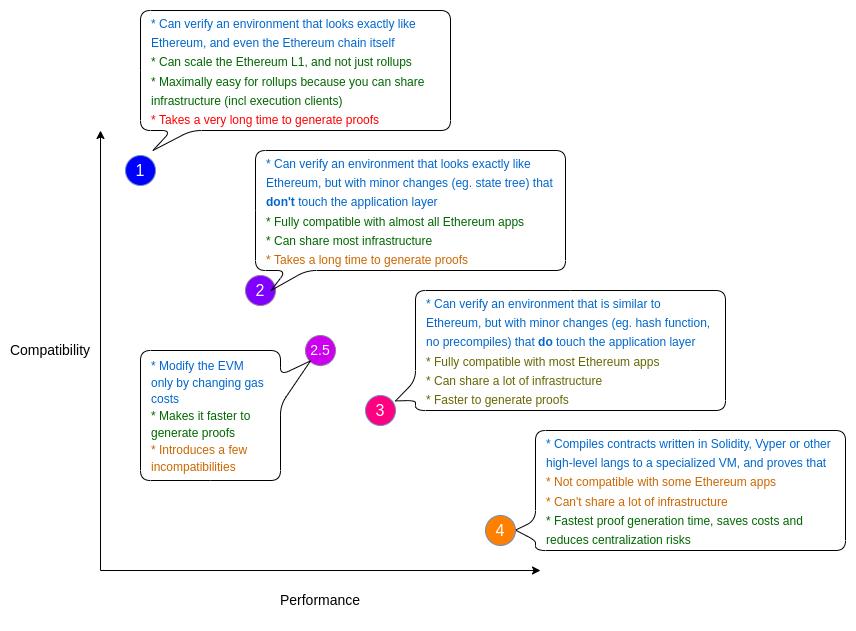

Since the EVM was not originally designed with zk-proof computation in mind, it exhibits characteristics unfriendly to proof circuits—especially concerning special opcodes, stack-based architecture, storage overhead, and proof costs. zkEVM is a virtual machine that executes smart contracts in a way compatible with zk-proof computation, allowing the EVM's execution process to be verified more efficiently and cost-effectively using zk-proofs or validity proofs. Unlike OP Rollups, which simply replicate the EVM at the execution layer, building a ZK-friendly version of the EVM presents an additional challenge for ZK Rollups.

ZK rollups face difficulty achieving compatibility with the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). Proving general-purpose EVM computations in a circuit is significantly harder and more resource-intensive than proving simple operations (e.g., token transfers described earlier).

However, advances in zero-knowledge technology have reignited interest in wrapping EVM computations inside zero-knowledge proofs. These efforts aim to create a zero-knowledge EVM (zkEVM) implementation capable of efficiently verifying the correctness of program execution.

Like the EVM, zkEVM transitions between states after performing computations on certain inputs. The key difference is that zkEVM also generates zero-knowledge proofs to verify the correctness of every step in program execution. Validity proofs can confirm the correctness of operations involving virtual machine states (memory, stack, storage) and the computation itself (i.e., whether correct opcodes were called and properly executed).

The idea sounds great, but reality is harsh: current Rollups struggle to achieve both ZK-friendliness and EVM compatibility (let alone full equivalence). One must either fully replicate Ethereum L1’s execution layer—including hashes, state trees, transaction trees, precompiles—so that Ethereum L1 execution clients can directly process Rollup blocks, or abandon EVM compatibility entirely, redesign existing opcodes for provability in circuits, thereby enabling smart contract execution.

1.2.3 zkVM — Sacrificing EVM Compatibility for zk-Proof Efficiency

Representative Projects: Starknet, Zksync, RISC ZERO

zkVM sacrifices EVM compatibility, focusing instead on data proving and state updates. It finds a common abstraction layer between cryptography and high-level programming languages, providing a universal framework for diverse applications.

Starkware benefits from early entry and strong technical accumulation in the ZK space, giving it a leading position technologically. It represents a ZK-centric architectural approach, building around ZK with Cairo VM and the Cairo language. However, Cairo has a steep learning curve.

ZKsync’s framework blends features of both EVM and ZK systems, integrating Solidity with its proprietary circuit language Zinc, unifying them at the IR level within the compiler. Its advantage lies in the LLVM-based compiler core supporting multiple languages.

RISC Zero uses the RISC-V architecture to build a simulator, allowing developers to write programs for zkVM using general-purpose languages like Rust, C/C++, and Go. This removes the limitation of expressing logic solely in Solidity and enables chain-agnostic code development.

1.2.4 Privacy zkVM — Combining zk-Friendliness with Native Privacy to Spark New Ecosystem Possibilities

Representative Projects: Aleo, Ola, Polygon Miden

Blockchain operates as a public ledger where all transactions are recorded on-chain, meaning asset-related state changes tied to addresses or accounts are transparent. Beyond scalability solutions, some blockchain teams believe privacy is the next essential functionality to implement.

Privacy zkVM goes beyond typical zk-friendly scaling properties. Thanks to native privacy support in its programming language, developers can build privacy-focused dApps on top, unlocking novel use cases and powerful narratives—such as completely solving MEV issues or ensuring user data ownership. That said, the complexity of Privacy zkVM designs requires large technical teams and may take several years before practical deployment becomes feasible.

1.2.5 SVM — Performance Optimization Pushed to the Extreme: An Execution Environment Built for Speed

Representative Projects: Eclipse Mainnet, Nitro, MakerDAO Chain (maybe)

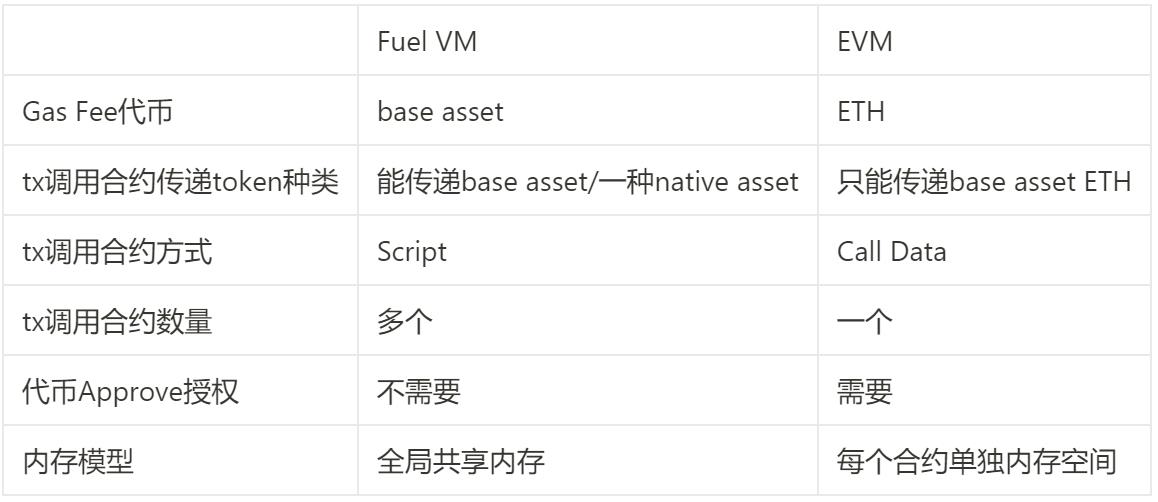

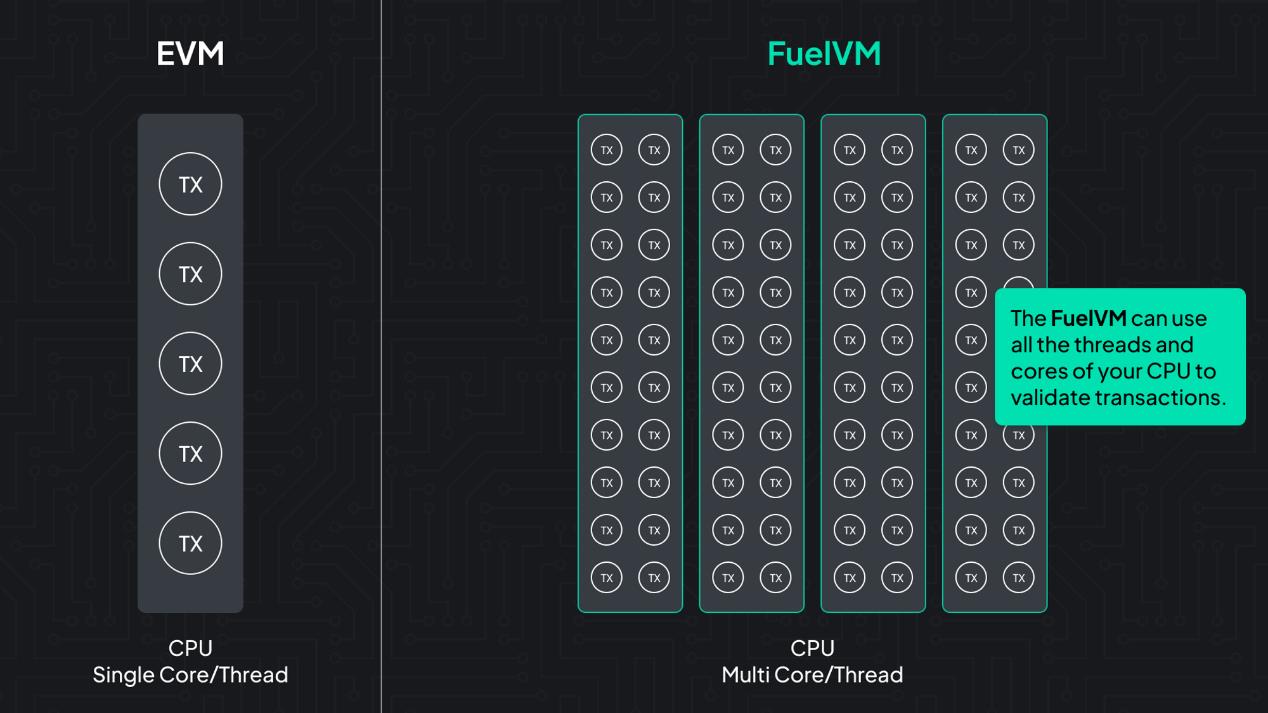

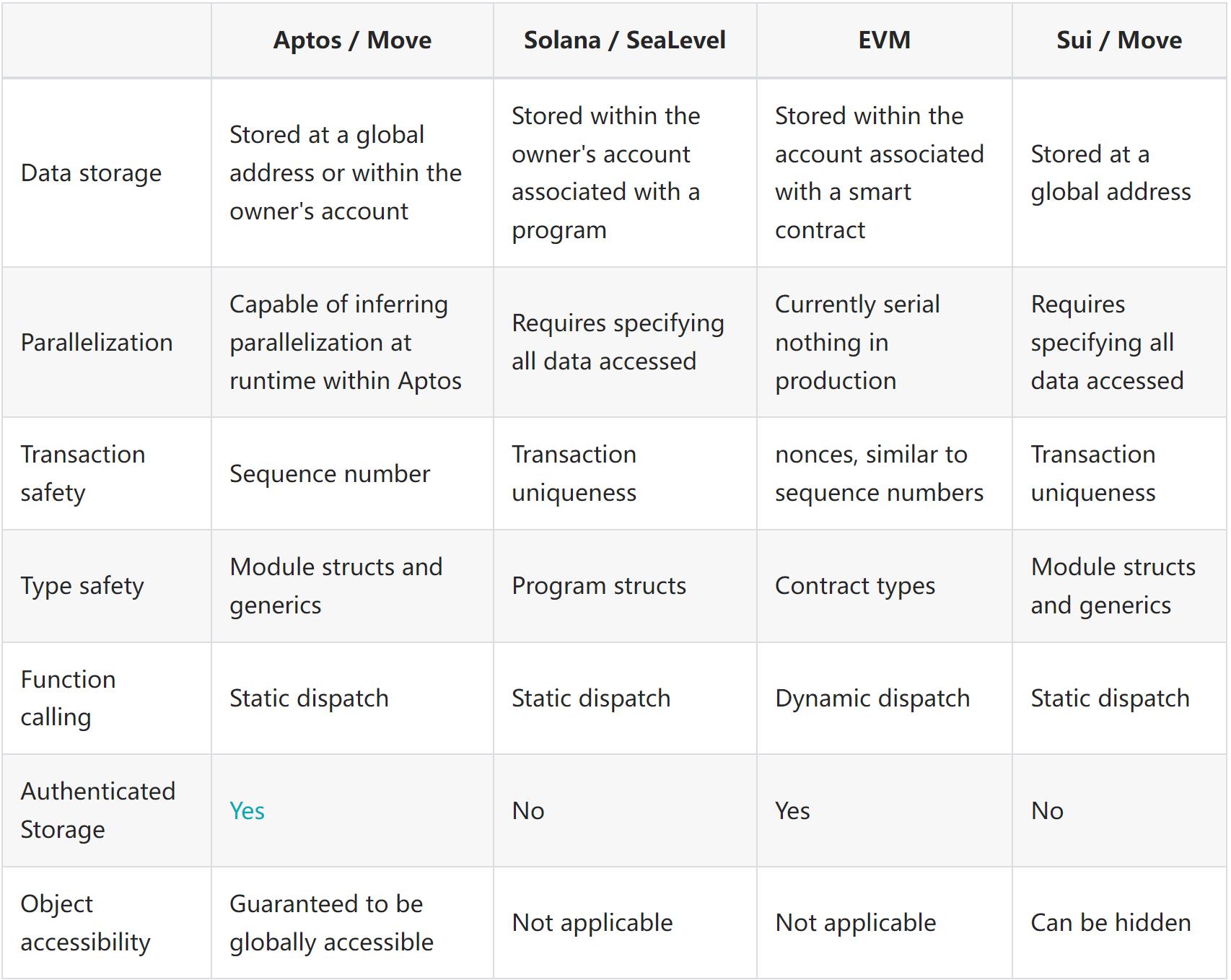

SVM, or Solana Virtual Machine, emphasizes high-performance execution environments, primarily using Rust for writing smart contracts. Unlike single-threaded EVM and EOS WASM execution environments, SVM achieves concurrent execution of non-overlapping transactions and read-only transactions by requiring Solana transactions to declare all states they will read or write during execution.

Additionally, to enable fast validation and broadcasting of large volumes of transaction blocks, Solana employs pipeline optimization—a technique borrowed from CPU design—in its transaction verification process. This involves processing a stream of input data through a series of stages, each handled by dedicated hardware. A classic analogy is a laundry setup with washing, drying, and folding machines working sequentially on multiple batches: washing precedes drying, which precedes folding, yet each operation is performed by separate units.

Moreover, SVM is register-based and has a much smaller instruction set compared to EVM, making it easier to generate zk-proofs for SVM execution. For optimistic rollups, a register-based design simplifies checkpoint setup.

1.2.6 Fuel VM — Maximized Performance: A Parallel Virtual Machine Under the UTXO Framework

Representative Project: Fuel

Fuel VM improves upon frameworks derived from EVM, Solana, WASM, BTC, and Cosmos. Compared to EVM, it has the following features:

Most uniquely, Fuel not only sets access lists similar to SVM—enabling parallel execution of non-overlapping transactions—but also adopts the UTXO model, distinguishing between token UTXOs and contract UTXOs, further improving access efficiency and computational throughput.

Furthermore, Fuel VM offers a robust and seamless developer experience through its domain-specific language Sway and toolchain Forc. Its development environment retains advantages of smart contract languages like Solidity while incorporating paradigms from Rust's tool ecosystem.

Future upgrades to Fuel VM will enhance the Sway language, including compiler optimizations for bytecode size, support for additional backends (EVM backend currently in development), economically optimized abstractions, migration of more applications from Solidity/Vyper to Sway, and improved reentrancy analysis at the compiler level.

1.2.7 ESC VM — Heir to Ordinal/Smartweave: Computation Layer on Ethereum

Representative Project: Ethscriptions Protocol

ESC VM, or Ethscriptions Virtual Machine, is a smart contract scheme proposed by the Ethscriptions Protocol. Ethscriptions Protocol itself is an Ethereum-based protocol similar to BTC Ordinals, focused on exploring low-cost alternatives distinct from traditional smart contracts and L2s.

Ethscriptions allow users to bypass smart contract storage and execution at extremely low cost by leveraging predefined protocol rules applied to calldata within transactions. Simply put, any successful Ethereum transaction whose calldata conforms to valid data specifications, is unique, and has a non-zero "to" address is considered a legitimate Ethscription, with the "from" address as creator and "to" address as owner.

Initially, each Ethscription resembled NFTs—for instance, image NFTs encoded directly into calldata using Base64 format:

Recently popular eths follow the brc-20 specification to create Ethscriptions:

The smart contracts introduced by ESC VM are called “dumb contracts”—logical contracts published publicly but not interacting on-chain via EVM. Additionally, ESC VM introduces a special format—"computer commands"—where Ethscriptions created using this format are recognized by ESC VM as interacting with dumb contracts, e.g., Deploy (deploy a dumb contract), Call (invoke a dumb contract).

This approach has limitations: first, functions in "dumb contracts" are not payable. To send ETH via a dumb contract, one must use a "bridge contract," which carries risks of control abuse and asset theft. Second, there is an ecosystem entry barrier—arbitrary creation of dumb contracts is not allowed; their code must be defined through governance proposals in the Ethscriptions Protocol.

In summary, ESC VM uses Ethereum L1 as a data storage layer and builds a computation layer atop it, placing contract logic, calls, and related data within Ethereum transaction calldata. The global state consensus of ESC VM relies on client-side consensus, analogous to Arweave’s SmartWeave logic—except SmartWeave uses Arweave as its data storage layer.

1.2.8 Bit VM — An Interesting Research Experiment: Peer-to-Peer Execution Channels on Bitcoin

Representative Project: ZeroSync

On October 9, Robin Linus, founder of ZeroSync, released a whitepaper titled “BitVM: Compute Anything On Bitcoin.” Strictly speaking, it is not a VM but an attempt to create a Turing-complete computational space where contracts are stored on the Bitcoin blockchain, but their logic is executed off-chain. If one party suspects breach, they can initiate a challenge on-chain; if the counterparty fails to respond correctly, the challenger can claim all funds in the contract.

Its main advantage is granting Turing completeness to Bitcoin without modifying the Bitcoin protocol, introducing new opcodes, or requiring soft forks—making it immediately applicable.

However, its drawbacks are evident: first, it only supports transactions between two parties (one proves, one verifies); second, creating a contract requires generating vast amounts of data and pre-signing numerous transactions, resulting in high off-chain storage costs.

Below is a brief overview of the technical logic:

(1) Point Input Commitment

Point input commitment allows the prover to set input values 0 or 1 for logic gates. This commitment contains two hash values H(A0) and H(A1). The prover reveals a preimage—e.g., A0 sets input to 0, revealing A1 sets input to 1.

(2) Logic Gate Commitment

With input values established, arbitrary logic gates can be composed in Bitcoin scripts using Bitcoin’s AND, NOT, and other opcodes.

(3) Binary Circuit Commitment

By combining hundreds of millions of logic gates into a binary circuit, Turing completeness can be achieved. To commit this binary circuit to the Bitcoin network, all logic gates must be placed within leaf nodes of a Taproot address.

(4) Challenge-Response Phase

Committing the circuit on-chain is insufficient—both parties need an effective way to verify the correctness of computation results. Ideally, the contract runs off-chain, both parties cooperate, and agree on outcomes. But in case of disputes, a challenge-response mechanism verifies results and enforces balance distribution via Bitcoin scripts.

Therefore, BitVM is far from being a Bitcoin rollup or L2—it lacks a complete virtual machine execution environment, global state, high-level languages for complex smart contracts, and easy interaction for arbitrary users. To put it plainly: BitVM is like building a room-sized supercomputer in an age where everyone uses mobile devices.

1.2.9 MoveVM — A Legacy of Facebook’s Web2 DNA

Representative Projects: Aptos, Sui

Move is a programming language designed for writing secure smart contracts, initially developed by Facebook to support the Diem blockchain. After Diem’s discontinuation, projects like Aptos and Sui carried forward the Move language. The defining feature of Move-based blockchains is global storage, structured as a tree rooted at account addresses, where each address can store resource data and module code.

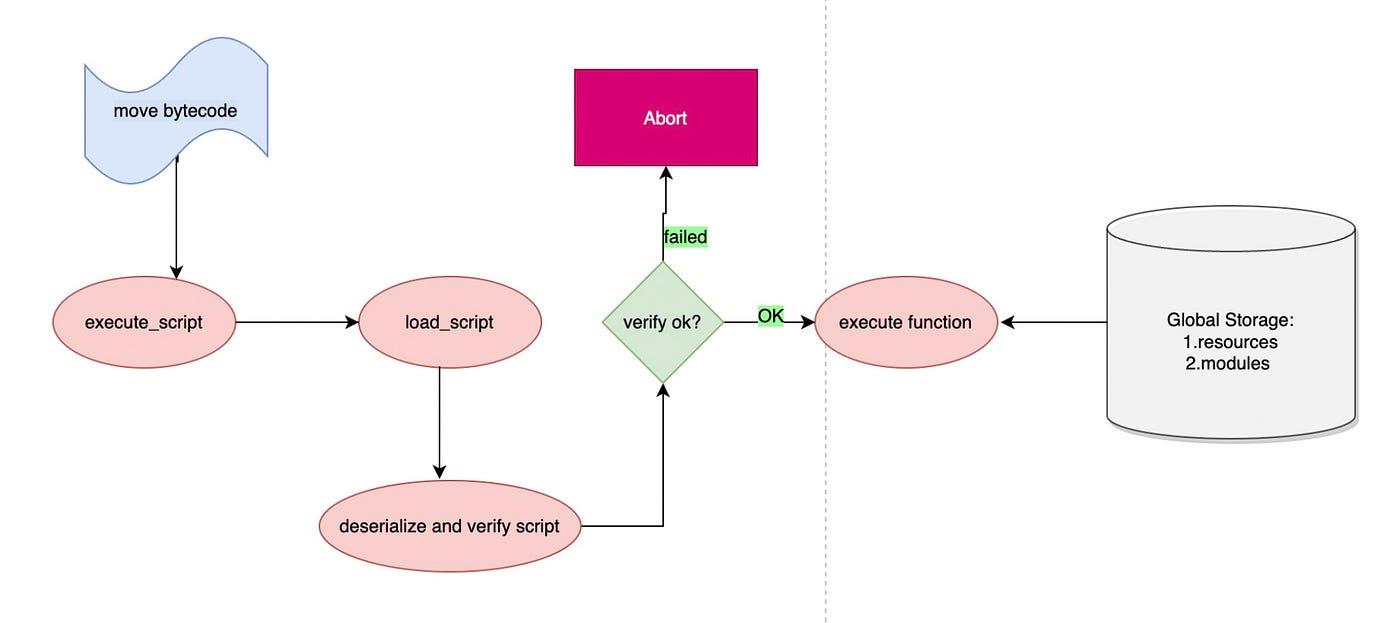

Move supports two types of programs: modules and scripts. Modules are libraries defining struct types and functions operating on those types. Struct types define the schema of Move’s global storage, and module functions define rules for updating storage. Modules themselves are also stored in global storage. Scripts serve as entry points for executable files—similar to the main function in traditional languages—and represent temporary code snippets not published in global storage.

In summary, Move modules resemble dynamically loaded library modules in system executables, while scripts resemble main programs. Users can write custom scripts to access global storage—including calling modules—while publishing modules or executing scripts occurs via the Move VM.

1.3 Ecosystem Development Trends

Given the immense network effects of EVM today, attracting EVM users to non-EVM chains has become the primary growth vector for emerging blockchain projects. This shift could unlock greater dApp composability and connectivity, potentially triggering faster user growth in the coming years.

1.3.1 Wallet Frontend Compatibility

Bringing EVM users to non-EVM chains has historically been a major hurdle, but the recent launch of MetaMask Snap aims to break this barrier. EVM users can continue using MetaMask without switching wallets. Thanks to Drift’s open-source contribution implementing an excellent MetaMask Snap integration, the UX is equivalent to interacting with any EVM chain. Eclipse mainnet users will be able to interact with native apps within MetaMask or use Solana-native wallets (like Salmon).

1.3.2 VM Backend Compatibility

1.3.2.1 Transpilers / Compilers

Representative Project: Warp

Warp is a Solidity-to-Cairo transpiler, already completed by Nethermind, a well-known Ethereum infrastructure team. Warp translates Solidity code into Cairo, though the resulting Cairo programs often require manual adjustments and additions (e.g., calling built-in functions, optimizing memory usage) to maximize execution efficiency.

1.3.2.2 Bytecode Interpreter / VM Compatibility Layer

Representative Projects: Kakarot, Neon EVM

Kakarot is an EVM bytecode interpreter written in Cairo and deployed as a smart contract on Starknet. It simulates EVM aspects such as stack, memory, and execution via Cairo smart contracts. Compared to code transpilation, Kakarot implements EVM opcodes and precompiles line by line, and includes additional components like Account Registry and Blockhash Registry to handle address mapping and block information retrieval, achieving higher native compatibility.

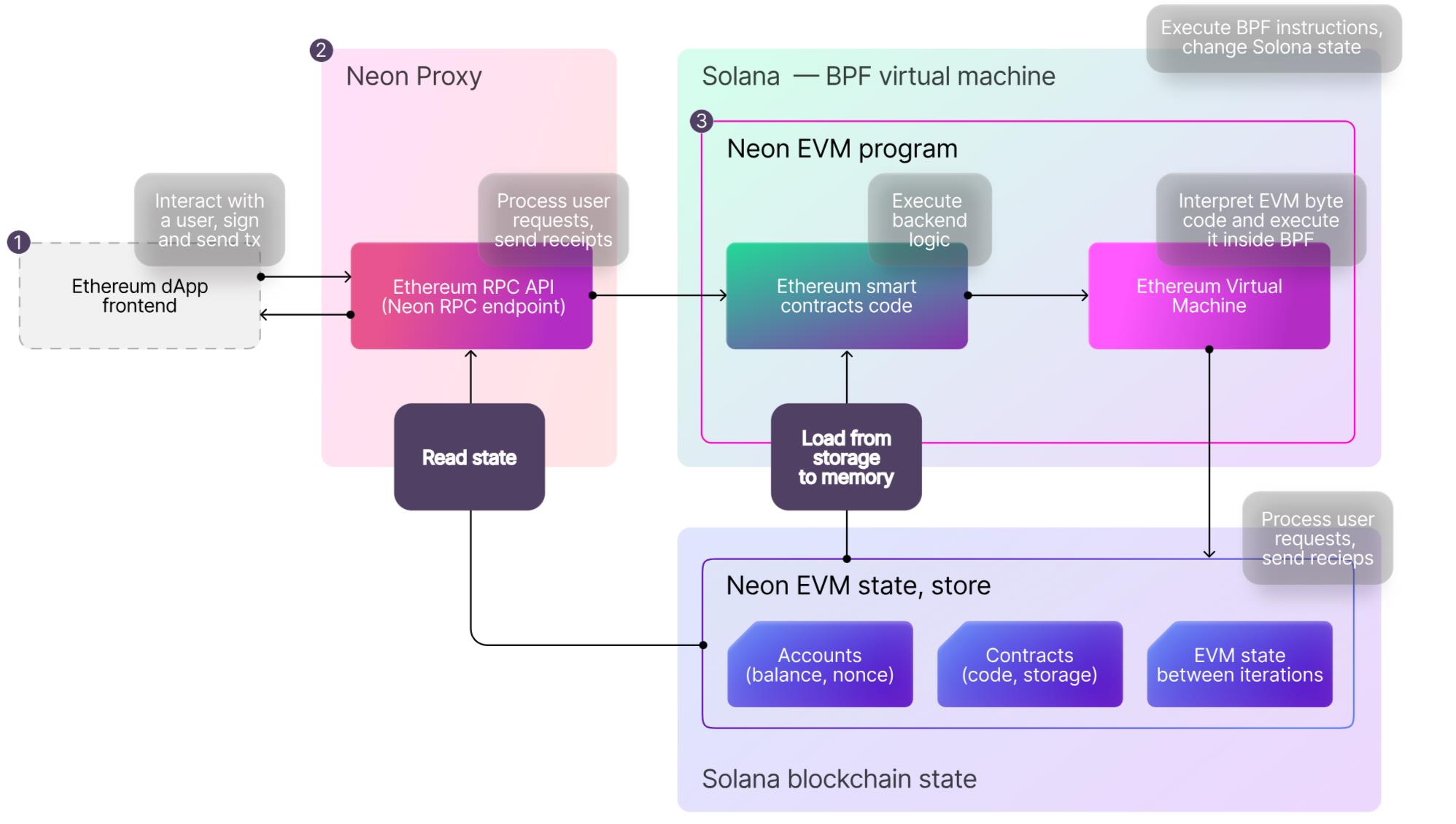

Neon EVM is an EVM implemented as a smart contract deployable on any SVM chain. Eclipse mainnet uses SVM as its execution environment but gains full EVM compatibility—including EVM bytecode support and Ethereum JSON-RPC—via Neon EVM, achieving higher throughput than single-threaded EVMs. Moreover, each Neon EVM instance has its own local fee market: a cap exists on compute units per contract interaction per block (set at 1/4 of total block compute units). Thus, users only pay priority fees during high-demand interactions or when blocks are full. In this sense, deploying applications grants near-appchain advantages, reducing negative impacts on user experience, security, or liquidity caused by congestion from specific contract interactions.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News