The Collapse of the FTX Empire: Demystifying Market Makers

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Collapse of the FTX Empire: Demystifying Market Makers

Whether in traditional markets or crypto markets, for the average investor, talking about market makers always feels like playing a game of blind men touching an elephant.

Author: Yaoyao

FTX collapsed, an empire crumbled, a series of top-tier platforms suffered severe blows, and market makers and lending firms were hit hardest: Alameda, one of the largest crypto market makers, was wiped out in this fiasco and officially ceased trading on November 10; DCG’s market-making and lending arm Genesis also faced solvency issues.

The collapse of major market makers, massive capital losses, and sharp one-sided market moves... triggered unprecedented panic among industry market makers. Amid the aftershocks, market making ground to a halt, communities and projects faced immense stress tests, and crypto market liquidity plummeted.

Whether in traditional or crypto markets, for retail investors, discussing market makers always feels like playing a game of blind men touching an elephant.

Now let's start from the beginning and demystify market makers.

Table of Contents

01. Market Makers in Crypto

- What are market makers, how do they make markets, and how do they profit?

- Market makers in the crypto market

- The role of market makers

- Market making strategies

- Opportunities, risks, and the Wild West

02. Yes or No: Is Everyone a Market Maker?

- Market Makers vs. Automated Market Makers

- AMM: Everyone Can Be a Market Maker

- Why Do LPs Lose Money?

03 Collapse of Top Market Makers: After the Market Loses Liquidity

- Market Makers in the Domino Effect

- What Happens When the Market Loses Liquidity?

- How DODO Meets Market Making Needs

01.Market Makers in Crypto

What Are Market Makers, How Do They Make Markets, and How Do They Profit?

According to Wikipedia, a market maker (MM) is known as a "specialist" in the New York Stock Exchange, a "bookmaker" in Hong Kong's securities market, and a "market creator" in Taiwan.

As the name suggests, a market maker creates a "market."

In traditional finance, a market maker is a commercial entity—typically a brokerage firm, large bank, or other institution—whose primary function is to create liquidity by buying and selling securities in the market.

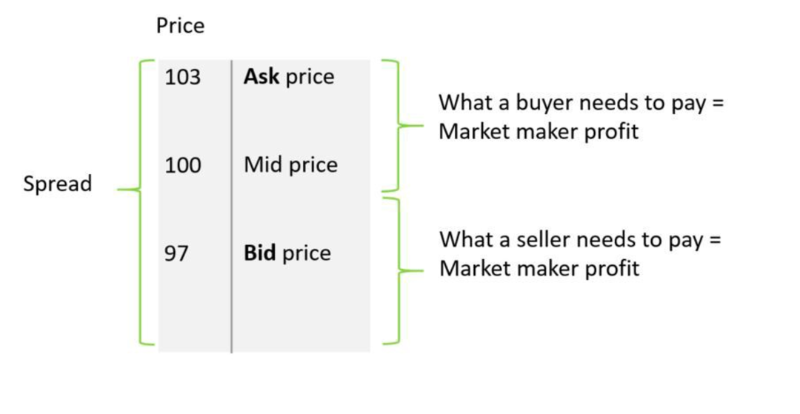

Market making is an established financial practice where market makers provide liquidity and depth to the market. Buyers and sellers don't need to wait for counter-parties; as long as a market maker steps in as the counterparty, trades can be executed. Market makers profit from the spread—the difference between the bid and ask prices—known as the bid-ask spread. This spread is their main source of profit (though some exchanges also rebate fees to designated market makers to boost trading volume and profitability).

In liquid markets with many buyers, sellers, and market makers, spreads are small, so market makers must execute high volumes to profit. They use sophisticated quantitative algorithms to build very short-term positions—from seconds to hours. The more volatile the market and the higher the trading volume, the greater their potential profits.

Buying this asset costs 103, selling it yields 97; the market maker earns a 6-point spread.

In short, market making involves providing two-way quotes—buy and sell—for any given market, establishing order book depth. Without market makers, markets would be relatively illiquid, hindering trade convenience.

Market Makers in Crypto

In both traditional and crypto markets, liquidity is the lifeblood of all trading, and market makers are the helmsmen. In crypto, market makers are often called liquidity providers (LPs), which directly highlights a key point: like traditional markets, crypto markets need market makers to help guide the "invisible hand" and solve liquidity traps.

This liquidity trap manifests as a vicious cycle: crypto projects need participants (exchanges and investors) to contribute token liquidity, yet these participants only join once tokens have sufficient market liquidity. And this is where market makers come in.

Simply put, market makers use liquidity to breed liquidity. A project typically relies on market makers to provide liquidity, confidence, and upward price momentum until trading volume is sufficient to sustain its own ecosystem.

How professional crypto market makers solve market liquidity issues. Source: Wintermute

What Is the Role of Market Makers?

Take cryptocurrencies as an example. The most fundamental role, repeatedly emphasized, is liquidity—because liquidity underpins any efficient market.

-

Strong pricing power: Market makers continuously track price movements and determine fair market value, offering reliable reference quotes. For instance, platforms like 1inch route funds across different pools while also sourcing quotes from market makers such as Wintermute.

-

Enhanced market liquidity: Investors can trade directly with market makers without waiting for or seeking counterparties. Providing two-way quotes is at the core of liquidity provision.

-

Improved market efficiency: Market makers quote across multiple platforms and arbitrage away inefficiencies, enhancing overall market efficiency. For example, Kairon Labs currently connects APIs from over 120 exchanges, helping mitigate price volatility.

-

Facilitates new token launches and lowers issuance costs: Market makers drive rising trading volumes and help new tokens appear across multiple crypto exchanges.

-

Boosts trading volume and market expectations: Attracts investor attention, strengthens market confidence, and drives token prices upward.

-

Enables large block trades: Market makers naturally serve as counterparties for institutional block trades.

Market Making Strategies

A market making strategy refers to placing limit buy and sell orders to exploit price fluctuations, triggering orders and profiting from the bid-ask spread. This falls under high-frequency trading and is a risk-neutral order book arbitrage strategy—essentially what was mentioned earlier: middlemen earning spreads.

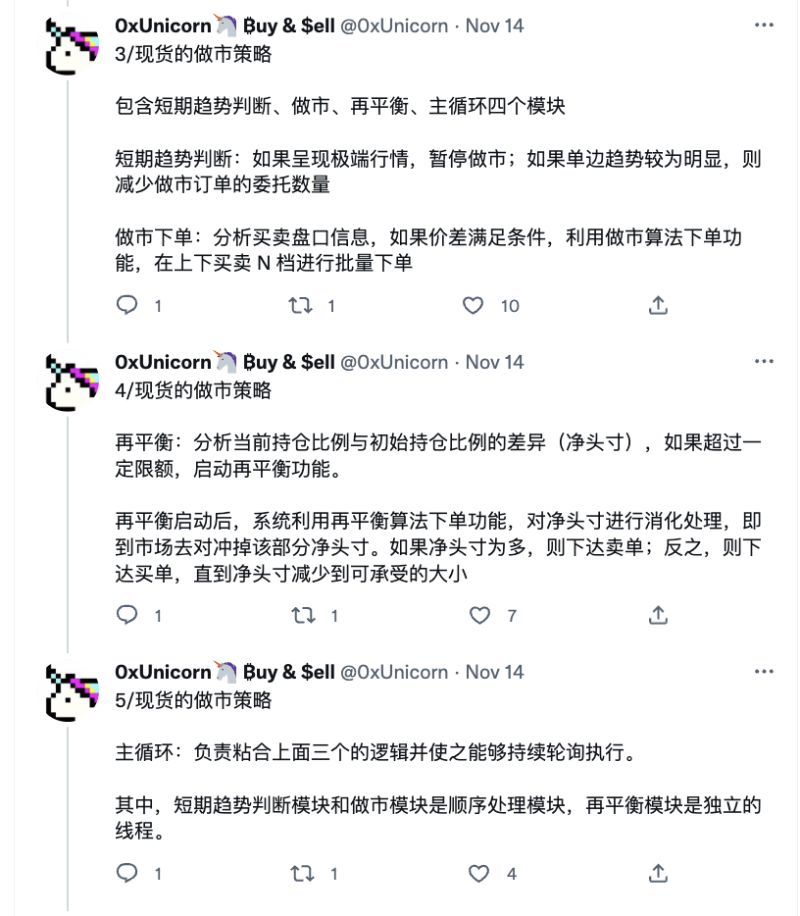

Twitter user 0xUnicorn detailed common market maker strategies categorized by spot and futures in a tweet, which we won’t reiterate here. More granular classifications include delta-neutral market making (self-hedging inventory risk), high-frequency “instant” market making, grid market making, etc.

https://twitter.com/0xUnicorn/status/1592007930328776706

https://twitter.com/0xUnicorn/status/1592007930328776706

At its core, market making strategies focus on the number of limit orders and the distance of bid/ask prices from the mid-price. Thus, classic strategies primarily study mid-price estimation, then place buy and sell orders appropriately around it. Consequently, market makers fear sharp one-sided market moves, as these lead to unidirectional fills and accumulation of risky inventory positions.

Risks, Opportunities, and the Wild West

As mentioned above, the primary risk stems from inventory risk.

Holding large inventories increases the likelihood that market makers cannot find buyers, creating a risk: holding excessive assets at the wrong time (usually during depreciation). Conversely, when asset prices rise, market makers may be forced to sell inventory at a loss to maintain operations.

In DeFi, handling market making risks tends to be more cautious. Take perpetual contracts, for example. Market makers often exploit funding rates (which anchor contract prices to spot prices) to arbitrage between spot/leverage and perpetual markets. In short: establish positions of equal value but opposite direction in both markets. Thus, under abnormal price volatility, market makers face significant liquidation risks due to large positions accumulated via funding rate arbitrage.

Opportunities arise from high-risk, high-reward scenarios. Even a $0.01 spread can yield $10,000 in profit if executed a million times daily. Market makers also offer leverage; when clients get liquidated, market makers seize their margin. According to Coinglass data, daily crypto liquidations range from $100 million to $1 billion—creating massive profit potential for market makers.

Undeniably, the crypto market remains early-stage. Compared to mature traditional financial market making, it still operates with wild abandon. Zooming into certain details: relatively low asset liquidity; significant slippage risks; flash crashes when large orders appear or when numerous sell orders cancel the best bid on the order book. These characteristics often create hidden corners—or profits—for crypto market makers.

Overall, due to technological and regulatory factors, both crypto market makers and users still experience a chaotic, blind-men-touching-an-elephant perception.

Welcome to the Wild West. When a market maker promises a token issuer a specific trading volume, the next step becomes even more ambitious: promising the token price will reach a certain level. How?

-

Wash Trading: A novice places a large sell order and seconds later buys it back with their own funds. A sophisticated player uses smaller orders over longer periods and avoids detection by using multiple accounts instead of just one.

-

Pump-and-dump: Among all price manipulation tactics, pump-and-dump is especially common. Social media serves as the frontline—once FOMO kicks in, selling previously accumulated tokens generates profits.

-

Ramping: Creating the illusion of a big buyer. Market makers execute large trades over fixed periods to simulate strong demand. Again, FOMO takes hold—other traders rush ahead of the “big buyer” (only to lose). When the market notices, prices naturally rise. But once the activity stops, the phantom buyer vanishes mysteriously, and token prices likely crash.

-

Cornering: When multiple market makers exist for a token, one might attempt to corner the market by buying up most available supply, forcing others to raise prices to maintain their spreads.

Due to complete lack of regulation, these speculative tactics indeed appear in market makers’ execution strategies. Ultimately, they disrupt markets, erode confidence in traded assets, lose exchange trust, damage project reputations, and cause long-term losses.

02. Yes or No: Is Everyone a Market Maker?

Market Makers vs. Automated Market Makers

Although market makers (MM) and automated market makers (AMM) sound similar, they are entirely different entities.

As previously noted, in traditional finance, a market maker is an institution or platform that submits buy/sell orders for various securities across multiple exchanges, providing liquidity and profiting from bid-ask spreads.

An AMM, however, is a decentralized exchange (DEX) protocol. Unlike traditional exchanges that use order books, AMMs price assets based on specific algorithms, which vary by protocol. For example, Uniswap uses the formula: x * y = k, where x and y represent quantities of two assets in a liquidity pool, and k is a fixed constant ensuring total pool liquidity remains unchanged.

AMMs operate similarly to traditional order-book exchanges, both setting trading pairs (e.g., ETH/DAI). However, traders don’t need specific counterparties. In AMM systems, traders interact with smart contracts to “create” their own markets. Liquidity comes from liquidity providers (LPs), who earn fees from pool transactions in return for supplying capital.

AMM: Everyone Can Be a Market Maker

In traditional finance terms, an AMM simulates human market maker behavior through algorithms. In DeFi, however, it has evolved into a brute-force engine:

It uses automated algorithms to balance supply and demand within trading pools, avoiding situations in order-book models where one-sided markets deplete one token (no buyers/sellers left to trade). Unlike CEX market makers who profit from spreads and manage inventory strategically, DEX market makers differ—they also earn transaction fees. When these fees are distributed to LPs, they incentivize users to deposit idle assets into pools, thereby addressing shallow order book depth.

AMM-based DEXs have proven one of the most impactful DeFi innovations, breaking order-book limitations and enabling DEXs to challenge CEX dominance in crypto trading, making open, permissionless on-chain trading a reality. It is AMM that allows ordinary users to participate in market making permissionlessly, letting every DEX proudly declare: Everyone Can Be a Market Maker.

Permissionless, efficient, transparent, self-created markets, everyone shares in liquidity creation rewards. The vision painted by DEXs sounds almost too perfect.

Why Do LPs Lose Money?

Now let’s examine the gap between vision and reality.

First question: Will users definitely profit by becoming LPs and providing liquidity on DEXs? (A voice replies: Didn’t you forget impermanent loss?)

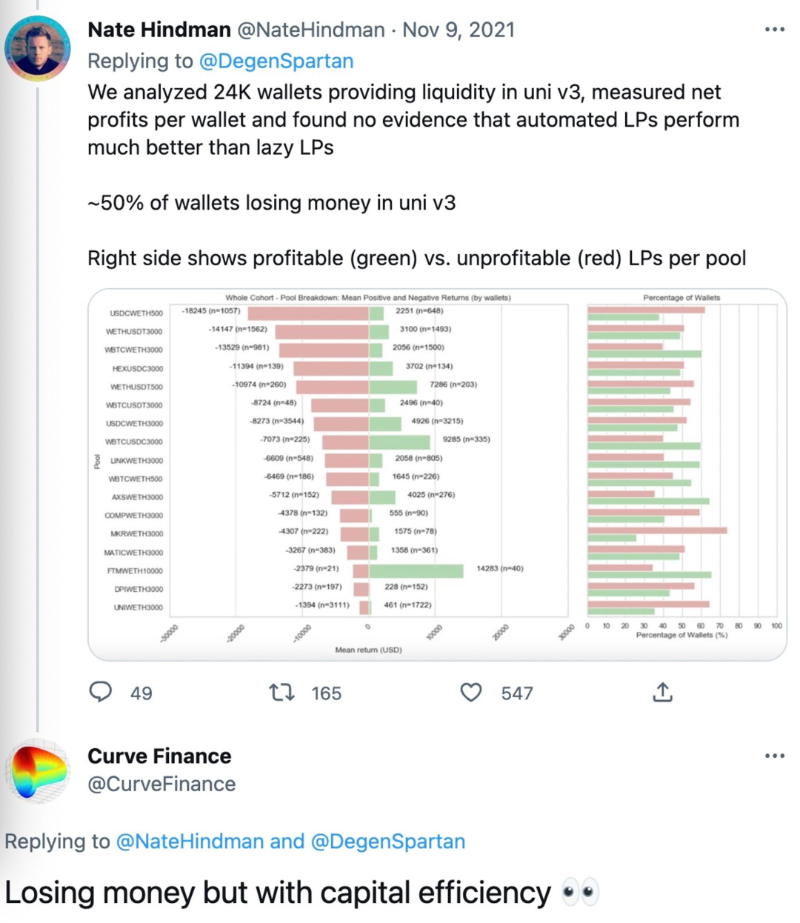

In a widely cited study on Uniswap v3 LP losses, rekt bluntly stated: Users would have been better off HODLing rather than providing liquidity on Uniswap v3.

As shown in the report, between May 5 and September 20, 17 pools with TVL > $10 million (accounting for 43% of total TVL) generated ~$200 million in fees from over $100 billion in volume. Yet, IL losses exceeded $260 million, resulting in a net loss of over $60 million. In other words, about 50% of Uniswap v3 LPs lost money.

While Uniswap v3 popularized leveraged liquidity provision—narrowing the price range and improving capital efficiency by eliminating unused collateral—this leverage increases fee earnings but also raises risk, as highly concentrated positions face greater impermanent loss.

The root lies in Uniswap v3’s design goal: customized market making. Greater user control makes market making more complex. LP returns depend heavily on market timing ability, increasing decision costs and leading to uneven outcomes. This design also enables JIT (Just-In-Time) attacks—adding and removing concentrated liquidity within the same block to capture disproportionate fees.

Higher capital efficiency but lower net returns—that’s not what LPs want.

https://twitter.com/NateHindman/status/1457744185235288066?s=20&t=jb-YsLK25pE8GuHZaMAudg

https://twitter.com/NateHindman/status/1457744185235288066?s=20&t=jb-YsLK25pE8GuHZaMAudg

This leads to the next question: Do DEX LPs always lose money?

Let’s answer simply: Whether DEX market makers profit depends not only on skill, but mainly on the pool model they use.

-

Traditional AMM model pools—The profit logic for regular LPs is no different from professional market makers. Both are constrained by the AMM function. Ultimately, it’s a battle of TVL—whoever provides more capital captures higher fees.

-

Pools with customizable pricing—Such as Uniswap V3, Balancer V2, Curve V2, DODO V2. These allow market makers to actively influence pool pricing, leveraging price differences and lags between CEX and DEX markets to profit (and with many DEX aggregators today, better pricing increases the chance of being routed).

One reason LPs lose money is choosing unsuitable models.

Why do top DEXs offer customizable pricing pools? Not just Uniswap V3—when liquidity spreads evenly across curves, high slippage and fragmentation occur. Traditional AMMs aim to improve capital efficiency. Models like Uniswap V3, Balancer V2, Curve V2, and DODO V2 all move toward concentrated liquidity.

By contrast, active market making lets users concentrate liquidity in specific ranges, improving capital efficiency, reducing slippage, and increasing depth. But the downside is higher barriers for average users, making it more suitable for professionals. While profits may rise, so does risk—ordinary users simply can’t match professionals in skill and market sensitivity.

“Everyone can be a market maker”—we must reinterpret this slogan: Anyone can become a market maker, but not everyone can be a good one.

03. Collapse of Top Market Makers: After the Market Loses Liquidity

Market Makers in the Domino Effect

FTX’s collapse severely impacted a series of top platforms, with market makers and lenders hit hardest: Alameda, one of crypto’s largest market makers, perished in this chaos and officially halted trading on November 10; DCG’s market-making and lending subsidiary Genesis suspended redemptions and new loans due to solvency issues caused by FTX’s collapse, while seeking $1 billion in emergency funding from investors.

As a critical domino piece, the impact of market maker collapse includes:

-

Sharp decline in market liquidity

FTX collapse → market maker implosion → liquidity gap. With top market makers gone, a significant drop in market liquidity is inevitable. Other market makers also suffer losses from FTX’s failure, further widening the gap. A harsh reality: crypto liquidity is dominated by just a few firms—Wintermute, Amber Group, B2C2, Genesis, Cumberland, and Alameda. Less than six months after the Three Arrows Capital crisis, the market darkens again, making market making extremely difficult.

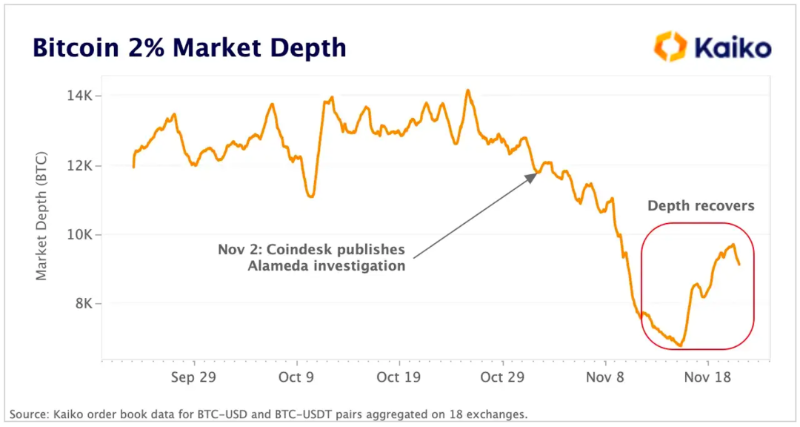

According to Kaiko data tracking, since CoinDesk revealed Alameda’s financial state, BTC liquidity within 2% of mid-price dropped from 11.8k BTC to 7k—the lowest since early June. Numerous data points in that article show Alameda’s collapse and other market makers’ losses significantly impacted overall market liquidity.

Fortunately, depth has slightly recovered in the past week, indicating market makers are redeploying capital. But clearly, the pace is slow.

BTC amount within 2% of mid-price rose from 6.8k to 9.1k. In dollar terms, market depth increased from $112 million to $150 million. Source: Kaiko

-

Token liquidity and project stress tests

Alameda invested in dozens of projects, holding millions in low-liquidity tokens (as a market maker, they were also primary liquidity providers). Though full details of Alameda and FTX’s token holdings remain unclear, the Financial Times’ balance sheet analysis calls it “a systemically important market maker.” Especially for tokens beyond BTC and ETH, this extreme market condition poses a massive stress test for affected projects.

Take SOL (Solana), one of Alameda’s major bets. According to CoinDesk, Alameda held roughly $1.2 billion in SOL as of June 30. SOL was one of the best-performing tokens during the 2021 bull run, but now trades down 95% from its all-time high.

This scale of collapse: first causes liquidity crunches and risks to DeFi via mass liquidations, potentially burdening lending protocols with bad debt; second, triggers loss of confidence, mass staked token withdrawals, increasing disruption risks, lowering network security, and reducing attack costs.

In the weeks following FTX and Alameda’s implosion, SOL plunged from ~$35 to ~$11—a 68.5% drop. Source: TradingView

-

Double collapse of confidence and trust

More importantly, a dual collapse of confidence and trust.

Confidence: The "black swan" event shook industry faith in so-called high-performance public chains and undermined user and supporter confidence in FTX’s ecosystem projects. Confidence is worth more than gold; fear is worse than hell. The crypto market has endured two Lehman moments in half a year—Luna/Terra and Three Arrows Capital—teaching users about uncertainty and spreading panic faster than any virus.

Trust: From Alameda’s collapse, we see how even top-tier market makers operated recklessly—using FTX customer funds improperly to fund their entire trading operation. Yet investors and projects had no way of knowing. This reflects the implicit trust transfer CeFi has demanded from the public since inception. But when even a trusted, well-backed, large-scale market maker reveals its raw ugliness, your faith in the crypto world shatters. Though we’ve said it many times: FTX / Alameda ≠ Blockchain.

After the Market Loses Liquidity

As noted earlier, liquidity is the engine behind any market.

When overall market trends turn bearish and top market makers withdraw, conditions worsen—project and investment stagnation follows, creating a vicious cycle (until fundamentals recover):

Market slowdown → liquidity drops or major crisis → sharp one-sided moves → reduced market making → lower trading volume and investment → further liquidity decline → deeper market slowdown.

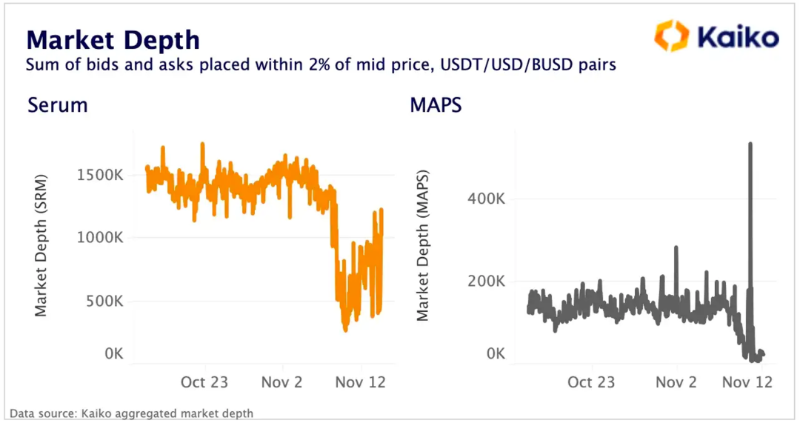

SRM and MAPS also saw dramatic depth declines, affected by Alameda. Source: Kaiko

To maintain crypto market liquidity, many market makers provide liquidity to blockchain exchanges and financial protocols. Therefore, in the absence of market making or with sharply reduced activity, trading volume and investment may shrink. We must distinguish: Liquidity normally dips during volatility—market makers pull bids/offers to manage risk and avoid adverse flows. But sudden drops caused by major crises or market maker withdrawals pose serious short-term challenges.

Currently, liquidity decline is more severe than in any prior downturn, and recovery during this bear market is extremely slow—indicating this liquidity gap may persist in the near term.

So what should be done?

How Does DODO Meet Market Making Needs?

As discussed, we’ve raised two main questions:

-

When AMMs optimize toward concentrated liquidity and becoming an LP may become challenging or even unprofitable, how can market makers generate returns?

-

When the FTX collapse wipes out top market makers and market liquidity dries up, how can trust be rebuilt and the true decentralized nature of crypto leveraged to deliver much-needed liquidity to projects—and genuine permissionless, efficient, transparent market making to market makers?

Regarding the second question, the answer is already self-evident: Use DEX, Use Blockchain. Return on-chain, to code, to “don’t trust, verify.”

For the first question, many protocols already offer liquidity management tools to help LPs manage risk and stabilize returns. Here, DODO offers one solution: bringing professional market makers on-chain.

In the article “Interview with DODO Market Maker: How to Improve Market Making Efficiency Using DODO”, Shadow Labs, a market maker, mentioned that after deducting gas and other fees, they achieve 30–40% net profit from on-chain revenue. For example, the WETH-USDC market maker pool on DODO generated $500K in net year-to-date profit, a net return of approximately 36.2% after expenses.

How is this achieved?

It’s well known that AMMs are often called “lazy liquidity” because traders cannot control price points, unlike traditional market makers who are more informed and flexible. This is where DODO steps in, pioneering the PMM (Proactive Market Making) algorithm. PMM uses price oracle inputs to adjust pricing curves—simple yet highly flexible. Flatter curves significantly improve capital efficiency, reduce slippage, and minimize impermanent loss. For comparative analysis of how different algorithms enhance concentrated liquidity efficiency, see “Deep Comparison of Uniswap V3, Curve V2, DODO Market Making Algorithms — Efficiency Gains from Concentrated Liquidity”.

Beyond these familiar features, let’s discuss DODO’s V2 upgrade launched in March this year: DODO Private Pools (DPP), or private pools, designed specifically for professional market makers.

As the name implies, private pools allow market makers to independently deploy their own capital and flexibly modify configurations during market making—including trading fee rates, external reference price i, curve slippage coefficient K, and support for adjusting pool capital size. All changes are triggered via smart contract calls by authorized accounts (either through the DODO DPPProxy contract or direct underlying pool calls—see DODO V2 Private Pool Operation Guide for details). Thus, these pools primarily serve professional market makers’ needs.

In terms of returns, according to DODO data, the WETH-USDC market maker pool on Polygon achieved a total return of 16%, while BSC-based market maker pools (launched end-July) reached total returns of 10% to 22% over the past four months—overall quite

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News