MM on the Offensive 3: Statistical Edge and Signal Design

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

MM on the Offensive 3: Statistical Edge and Signal Design

The absolute domain of market makers: speed.

Author: Dave

The Rise of MM 1: Market Maker Inventory Quotation System

The Rise of MM 2: Market Maker Order Book and Order Flow

The first two episodes mentioned order flow and inventory-based pricing, making it seem like market makers can only passively adjust. But do they have any proactive tools? The answer is yes. Today we'll introduce statistical edge and signal design—the "micro alpha" that market makers pursue.

1. What Is a Market Maker's Alpha?

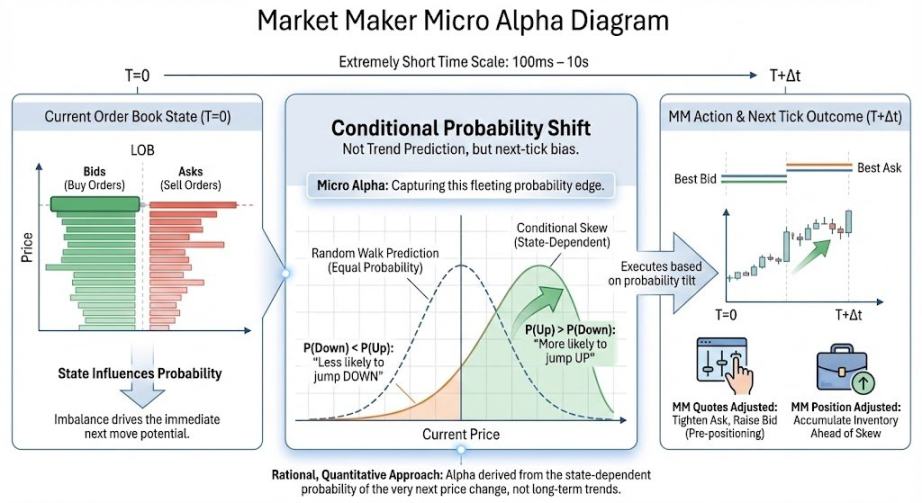

Micro alpha refers to the "conditional probability shift" in the next price move direction / mid-price drift / trade asymmetry over an extremely short time scale (~100ms to ~10s). Note that the alpha seen by market makers (mm) isn't about trend prediction or guessing up/down moves—it only requires a slight probability edge. This is different from what most people mean by alpha. Let’s break it down in plain terms:

A market maker’s statistical advantage means determining whether, within a very short time window, the current order book state tends to push price to move first in one direction. If mm can calculate, using certain indicators, the probability of the next millisecond’s price movement, they can: 1) be more willing to buy when an upward move is more likely; 2) cancel buy orders faster when a downward move is imminent; 3) reduce exposure during risky moments.

The financial foundation for predicting the next price move lies in the fact that, due to factors like order flow, outstanding order volume, and cancellation ratios (which we’ll discuss shortly), the market isn’t undergoing pure “random walk” Brownian motion in the short term—it has directional bias. This is the financial interpretation of the mathematical concept "conditional probability."

With such alpha, market makers can actively steer prices directionally—finally earning money from price positioning rather than just spread as a service fee.

2. Introduction to Classic Signals

2.1 Order Book Imbalance (OBI)

OBI examines which side has more presence near the current price level—it’s a normalized volume differential statistic.

The formula isn’t complicated—it’s just a proportional sum logic: comparing bid versus ask volume. OBI approaching 1 means almost all are bid orders, with deep support below. Approaching -1 means thick offers above. Near 0 indicates symmetric buying and selling.

Note that OBI is a "static snapshot"—a classic indicator, but not effective alone. It should be used together with cancellation ratios, order book slope, etc.

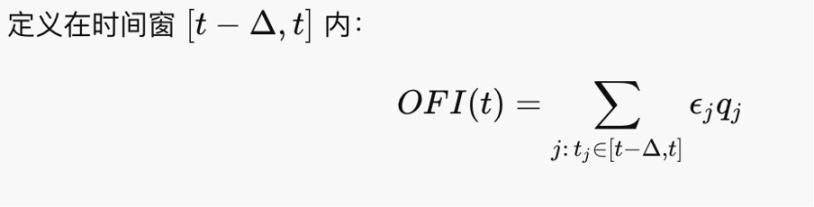

2.2 Order Flow Imbalance (OFI)

OFI looks at who has been actively attacking in the recent brief period. OFI is the primary driver of price changes because prices are pushed by taker orders, not resting limit orders.

It feels similar to net trading volume. Within the Kyle (1985) framework, ΔP≈λ⋅OFI, where λ is tick depth—thus OFI becomes the factor driving price movement.

2.3 Queue Dynamics

Most exchanges today use continuous double auction rules based on best price and FCFS (first-come, first-served). Therefore, submitted orders wait in line to be filled. The queue reflects limit order status, and the limit order status determines the state of the order book. Abnormal queue states (including replenishment and cancellation patterns) signal directional price movements—i.e., micro alpha.

Two key scenarios to watch in queues:

1. Iceberg: Hidden Orders

Example: Only 10 contracts are visibly posted, but once hit, another 10 are immediately replenished. The actual intent might be 1,000 contracts. In Episode 1, I described how manipulative market makers lower their cost basis—that method was essentially manually creating an iceberg. In practice, some traders hide true order size using icebergs.

2. Spoofing (False Orders)

Placing large fake orders on one side to create a false sense of "pressure," then rapidly canceling them before price reaches that level. Spoofing contaminates metrics like OBI and slope, artificially thickening the queue and increasing slippage risk. Some large spoofing orders can also intimidate the market and manipulate prices. The London exchange reportedly caught a forex manipulator in 2015 who used spoofing. In crypto, however, we can also spoof to harass manipulative market makers—but if your order actually gets filled, your exposure becomes huge.

2.4 Order Book Cancel Ratio

Cancel ratio estimates the rate at which liquidity "disappears":

Cancel↑⇒Slope↓⇒λ↑⇒ΔP becomes more sensitive. It acts as a leading instability signal ahead of OFI. CR→1: nearly pure cancellations. CR→0: nearly pure order additions. The math in this episode is simple—just interpret the charts visually.

CR↑⟹the passive side perceives rising future risk. Like others, CR isn't used alone—it's combined with OFI and similar indicators.

These may sound like basic old tricks, but market makers evolve quickly. With stocks moving on-chain, even JS-based market makers may soon enter on-chain market making. Still, these indicators remain useful and inspiring.

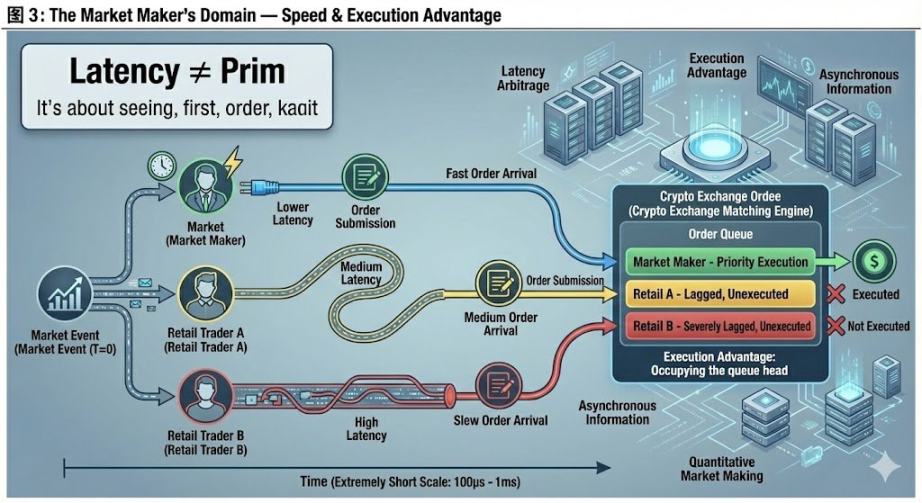

3. The Market Maker's Absolute Domain: Speed

We often hear in movies that a fund is superior because of faster network speed. Many market makers even move their servers physically closer to exchange data centers—why? In this final section, let’s discuss hardware advantages and the crypto-exchange-specific "execution priority."

Latency arbitrage isn’t about predicting future prices—it’s about executing trades at better prices before others have even reacted. In theoretical models, prices are continuous and information is synchronized. But in reality, markets are event-driven and information arrives asynchronously. Why asynchronous? Because receiving price updates from the exchange and sending your own order instructions both take time—this is a physical-world constraint. Even in fully compliant markets, differences across exchanges, data sources, matching engines, and geographic locations create latency. Thus, market makers with superior equipment gain control.

This tests the market maker’s own capabilities and has little to do with other players—so I consider it their absolute domain.

A simple example: suppose you want to sell. You quote at the best offer and expect execution. But I also want to sell—and because I see the price and react faster, I get filled first. Your inventory remains stuck, preventing you from restoring neutrality. Real-world situations are far more complex.

An interesting point: due to lack of regulation, nearly all crypto exchanges today can directly grant priority execution rights to designated accounts—essentially allowing certain accounts to jump the queue. This is especially common among smaller exchanges. It seems being "insiders" in crypto is as important as in academic research. The ability to execute safely is a crucial bridge from alpha theory to real-world practice.

This episode attempts to present content from the mm perspective. Actual operations are certainly more complex—for instance, dynamic queue management involves many practical nuances. Experts are welcome to comment.

Postscript: There’s a regret here. I originally wanted to use the title “Domain Expansion in Market Making” to discuss dynamic hedging and options, which I believe represent the most conceptually challenging part of market making—worthy of such a “domain expansion” moniker. But after working on it for a full day, halfway through writing, I realized I couldn’t systematically explain it, so I switched to micro alpha instead. @agintender wrote an article covering many professional hedging concepts—highly recommended.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News