End-to-End: The Decentralized Link Built by DID and On-Chain Data

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

End-to-End: The Decentralized Link Built by DID and On-Chain Data

When we push open the door to Web 3.0, all we see is desolation.

When we push open the door to Web 3.0, all we see is desolation.

DID cannot exist independently—it must grow and evolve together with other components of Web 3.0. DID functions like a gateway: there can be many such gates to ensure decentralization and prevent any single gatekeeper from monopolizing access and charging excessive tolls. But once users walk through the gate, there must be meaningful content waiting for them; otherwise, they will never stay. Without sustained user engagement, DID becomes water without a source, a tree without roots. Our discussion of DID is grounded in the belief that Web 3.0 represents the future.

As a front-end infrastructure for user entry, DID is the first step toward building a fully decentralized user experience. Behind it, however, must come complementary DApps such as SocialFi, GameFi, and DeFi. These require public blockchains as operating networks, decentralized storage solutions like IPFS and AR, middleware such as oracles and decentralized network nodes to maintain decentralized data flow, and finally on-chain verification mechanisms to ensure data authenticity and prevent fraud.

Within this architecture, SBT and DID serve highly similar functions. It's difficult to clearly categorize a product as purely DID or SBT. Even projects like BAB or GAL resemble PASS tokens—verifying information that has undergone centralized validation before being recorded on-chain. This process is fundamentally centralized, much like how USDT cannot be considered an algorithmic stablecoin.

Uniswap is a form of DeFi, but it would be incorrect to say DeFi consists only of Uniswap. Even within decentralized exchanges (DEX), there are distinctions between spot trading, derivatives protocols, AMM mechanisms, and order book models.

DID and SBT are functional descriptions for verifying personal identity. On-chain addresses, non-custodial wallets, decentralized email, and Web3 social protocols can all serve as carriers of DID or SBT. Current products marketing themselves around these concepts are largely early-stage promotional tactics.

Only under the protection of DID will users have the incentive to generate large volumes of valuable data. On-chain data analysis will then enter its 2.0 era—moving beyond today’s limited focus on DeFi and NFT market analytics. Directly analyzing user behavior offers far greater economic potential and could reshape how Web 3.0 applications iterate, breaking free from Ponzi schemes and mere imitation.

Starting from DID, accumulated native data will naturally grow richer—not just transaction records or whale address tracking. This wealth of data not only supports personal privacy but also becomes the monetization foundation for future Web 3.0 economic models, forming the core value layer of Web 3.0 applications rather than relying on the ad-driven models dominant among big tech firms today.

In short, what we need is complete decentralization. Any missing component or compromise with centralization leads to fragmentation and rupture—preventing Web 3.0 from fully realizing its advantages.

Identity Falls into the Data Web: The History of DID and Personal Data Integration

The medium is the message; the soul is identity.

Decentralization brings about the return of individual value. Viewed broadly, DID is a supporting measure for DeSoc. As Vitalik stated in "Finding Web3’s Soul," the future lies in a decentralized DeSoc society where DID becomes a unique personal identifier—not only within the Web 3.0 digital world but extending into broader real-world applications.

If everything must be decentralized, then identity should be no exception. Relying on Twitter or Facebook in a decentralized society is clearly unsustainable. Once Web 3.0 becomes new infrastructure, it may begin to feed back into the physical world—for example, DeBank already achieves some success by using on-chain addresses to display individuals’ on-chain activity as personal profile pages.

DeGenScore goes further, focusing on scoring individual on-chain activities. Credit systems have already proven powerful in the real world—from official credit reports to Alipay’s Zhima Credit—demonstrating that digitalized credit records offer superior risk control compared to traditional methods.

Of course, this line of thinking somewhat diverges from viewing DID strictly as a Web 3.0 entry point. It represents a conceptual expansion—treating DID as a tangible manifestation of the “soul” in a wider decentralized society. From this perspective, DID transcends its role as an access tool and becomes a node for interaction across on-chain and off-chain environments, between Web 3.0 and Web 2.0, and even between people. This vision is significantly broader than the simple notion of an entrance.

Nonetheless, we must recognize one key point: only after establishing DID as a functional entry point to Web 3.0 can such expansive connectivity become feasible over meaningful time horizons.

Next, R3PO takes us on a retrospective journey through internet usage.

Origins: The Emergence of Information Networks

Web 1.0: WWW and Browsers

After networking technologies moved out of DARPA labs and universities, the concept of civilian internet emerged. At that time, browsers and the World Wide Web constituted the entire idea of the network. IDs were primarily email addresses, personal domains, and forum usernames, while RSS and BBS became primary venues for data accumulation.

In other words, at the very beginning, ID existed prior to applications—just as is the case with Web 3.0 today.

Root of Evil: Growth and Abuse of Personal Data

Web 2.0, UGC, Blogs, iPhone, 5G, XR

From forums and blogs to Twitter and TikTok, the history of the internet has been one of continuous democratization of expression—from elite creators to everyone becoming media. From middle-aged professionals to teenagers coming online, by the time the concept of Web 3.0 arose, the internet had already become a taken-for-granted reality for Gen Z—ubiquitous and essential as electricity, water, or gas, with unquestionable status.

The 2016 U.S. election revealed Facebook’s sale of personal data, later confirmed to have enabled Cambridge Analytica to manipulate voter behavior. Two prerequisites made this possible: first, people leave extensive digital traces of their private lives online; second, users concentrate their personal data on specific platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

We must clarify: the concept of personal data came first, followed by debates over privacy rights. Over time, ID gradually shifted toward social tools—not rendering email obsolete, but reflecting changes in user habits. More accurately, Facebook became an alternative login option alongside email, implicitly assuming universal adoption of Facebook.

But the downsides of this model are increasingly evident today. Our personal data is siloed within apps like Google and Facebook. While we discuss privacy, we're really discussing our relationship with these platforms.

Whereas in Web 1.0 there was no separation between individuals and their data, in Web 2.0, social media giants and search engines alike have appropriated users’ labor—all under the guise of “free” services.

Under this paradigm, user IDs, game items, and social media data are at best only partially owned by users—if not outright controlled by platforms, granting users merely usage rights. GDPR offers partial protection of data sovereignty, but fails to return the economic value generated by user data directly to individuals. The situation continues to deteriorate.

DID Under Web 3.0: Reunification of Individuals and Their Data

What belongs to users returns to users; what belongs to protocols stays with protocols

In Satoshi Nakamoto’s original vision, users should ideally use a new address for every transaction to maximize privacy. In practice, aside from hackers and those who lose their seed phrases, few do this—it contradicts human nature’s preference for convenience.

Web 3.0 sits at a conceptual crossroads. Since its inception in 2004, it has evolved through phases of transforming traditional internet infrastructure and gradually integrating with blockchain. This integration didn’t happen overnight—it passed through eras defined by public chains like Bitcoin, Ethereum, and EOS, and now enters the multi-chain and Layer 2 era. Attempting to replace the WWW with a single public chain remains a work in progress. Current blockchain TPS still lags behind conventional networks in concurrency, and lacks efficiency advantages over centralized databases.

Still, we believe the next generation will grow up using Web 3.0. Therefore, we firmly affirm the importance of DID. There will be entry points—and likely multiple ones—but due to interoperability and decentralization trade-offs, their number will remain limited. Much like social tools, foundational infrastructure develops strong user stickiness. Human nature is lazy: people may change nicknames and avatars frequently, but rarely switch WeChat IDs or phone numbers.

Put differently, Web 3.0 will eventually take center stage, absorbing blockchain, DeFi, and NFTs into the construction of the next-generation internet. DID will become the most direct interface for interaction. We cannot yet confirm whether hardware like VR devices or software like wallets will prevail, but a solution will emerge.

The ultimate benchmark for success is the restoration of individual control over personal data. This ownership isn’t a promise from platforms to users—it’s a verifiable hash on-chain, immutable and unfalsifiable.

During FTX’s historic collapse, we could easily track fund movements across addresses, witnessing the fall of a giant in real time. Yet the problem persists: CEXs still control our data. When individual users lack control over their own addresses, they lose value.

Conversely, only when data and value are unified can the full power of decentralized systems be unleashed—ensuring individuals retain control over their own worth. Without genuine on-chain presence, no DID or SBT can claim true decentralization.

DID X On-Chain Data:Overview of Major Projects

Below is an overview of major projects involving DID functionality and on-chain data. Given DID’s broad scope, this includes SBTs, social protocols, login tools, and other systems generating substantial on-chain data—to deepen understanding of how DID integrates with on-chain data.

Social Protocols and On-Chain Data

The data types produced by social protocols mainly consist of personal data generated by users. Currently, the volume of user-generated data directly correlates with economic rewards such as airdrops. Operationally, these protocols fall into two categories: native Web3 social protocols and plugin-based protocols.

• Lens Protocol—Native Web3 Social Protocol

Lens Protocol, developed by the Aave team, launched in February 2022 and has garnered significant attention. Architecturally, it operates more like a meta-protocol—enabling developers to build custom social DApps on top of it. For instance, the official demo app LensFrens functions as a decentralized version of Twitter, allowing users to follow others with shared interests.

Image caption: lens protocol Source: lens protocol

Notable applications in the Lens ecosystem include Lenster (a decentralized social media platform), LensFrens (recommends profiles based on Web3 footprints), Phaver (a Share-to-Earn social app), Refract (trending leaderboard), Lenstube (decentralized 'YouTube'), Soclly (time auction network for creators), Clipto (custom video service for celebrities), and LensAI (an AI-powered NFT image generator).

Additionally, prominent projects in the official Lens ecosystem include:

Decentralized streaming service LensTube

AI NFT creation tool LensAI

Decentralized social protocol service Lenster

Decentralized social media app ORB

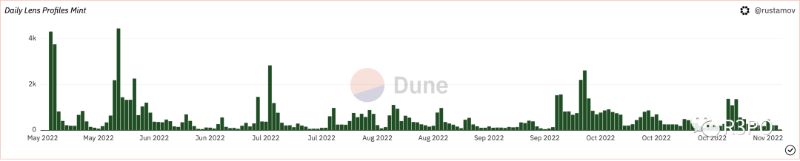

Image caption: Daily mint volume Source: dune.xyz

However, most apps have yet to achieve significant network effects. While Profile Mint counts exceed 100,000, daily active users hover around 600, and only 44% of registered users have posted content.

On Lenster, only about 10% of users post more than 20 times, while 36% publish just one post. Despite low overall activity, creator centralization is already apparent. (Detailed operational data)

• Mask Network—Plugin-Based Protocol

This model relies on platforms like Twitter and Instagram for user identification, while keeping data under user control—a compromise with centralization.

Yet as Meta improves NFT support and Twitter moves toward decentralization under Musk, plugin-based protocols like Mask are gaining traction—becoming connection points bridging Web 2.0 and Web 3.0.

Boosted by Musk’s acquisition of Twitter, $MASK briefly doubled in price. In the long term, Mask strengthened its position in July 2022 by partnering with Next.ID, becoming its preferred Decentralized Identity-as-a-Service (DIaaS) provider.

Next.ID is a decentralized identity aggregator building foundational identity layers. It employs a unique approach to decentralized identity, seamlessly integrating Web 2.0 and Web 3.0 accounts to create a highly interoperable environment where both coexist.

Ultimately, whether linking content from platforms like Twitter or integrating plug-in DID services like Next.ID, Mask is making user data more decentralized.

Personal Domains and Data

Personal domains are relics of the Web 1.0 era. Driven by ENS, they have become coveted entry tickets into Web 3.0, sparking widespread interest.

• ENS: The On-Chain Version of Personal Identifiers

ENS, or Ethereum Name Service, is a domain service operating on the Ethereum network. Primary domains function as cross-platform Web 3.0 usernames and profiles, enabling direct access to decentralized websites.

Vitalik once praised ENS as the most successful non-financial Ethereum application to date—analogous to a decentralized contact book.

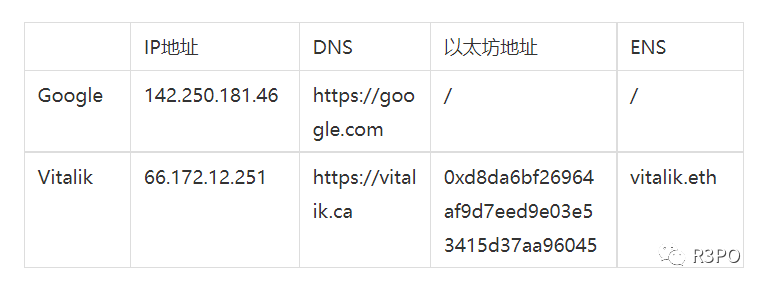

Launched on May 4, 2017, by Alex Van de Sande and Nick Johnson of the Ethereum Foundation, ENS aimed to create human-friendly domain services. Similar to how DNS maps IP addresses to readable names, ENS maps complex Ethereum addresses to readable .eth names:

Each ENS domain is also an NFT, fully on-chain and compliant with ERC-721. These can be minted and resold on NFT marketplaces like OpenSea. The highest recorded sale was paradigm.eth, purchased for 420 ETH.

ENS serves multiple purposes, with three main use cases emerging: user domains, Web3 business cards, and DID:

User Domain

ENS isn't just for display as an NFT—it's a functional Ethereum domain. By enabling IPFS services, it enables fully decentralized user experiences, giving individuals full control over website domains and data without reliance on centralized providers.

This evolution explains why, over five years, ENS has transformed from a simple Ethereum address resolver into a personal Web3 identity card.

For example, Vitalik uses vitalik.eth as his personal domain. Entering this in an IPFS-enabled browser automatically redirects to his page.

The final result appears as follows:

Image caption: Vitalik’s personal webpage Source: vitalik.eth

Beyond IPFS, ENS gateway operator ETH.LIMO now supports multiple content types, allowing each ENS-compatible storage layer—including IPFS, IPNS, Swarm, Skynet, and Arweave.

Although hosted on Ethereum, ENS is inherently cross-chain—for instance, it can bind addresses on Polkadot.

As on-chain domain systems gain popularity, ENS will continue expanding support to other blockchains, creating a unified, customizable on-chain domain system.

Web3 Business Card

Second, ENS domains can serve as digital business cards. After purchasing personalized domains, individuals and organizations can showcase them on platforms like Twitter to express unique identities.

On-chain user data typically includes timestamps, amounts, currencies, and NFT holdings—but lacks a unified identity system. In other words, we need something to represent ourselves.

ENS domains provide readable combinations of digits, letters, and symbols linked to on-chain addresses. Self-representation is a fundamental need—just as paper business cards served the analog era and internet domains defined the digital age, individuals have the right to shape and present their digital selves.

For instance, popular numeric ENS addresses reflect cultural aspirations. Nick Tomaino, founding partner of venture firm 1confirmation, bought «1492.eth», referencing Columbus’s first voyage in 1492. He calls ENS the perfect NFT series: «Some don’t consider ENS NFTs, but they’re actually the most widely held NFTs.»

Businesses also leverage ENS for branding. Puma famously changed its Twitter handle to «PUMA.eth» in February. According to ENS records, the associated website and Twitter profile were updated to reflect official Puma information.

Image caption: PUMA.eth Source: ens

DID

As a nickname for personal accounts, ENS serves as a unique identity marker. Especially when linked to both Web3 and Web2 social media, ENS allows unambiguous identification of individuals without needing their exact on-chain address.

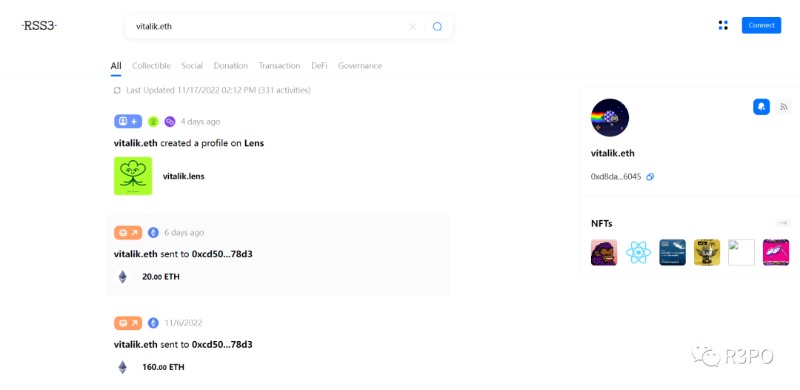

On Web3 social platform RSS3, users can directly search address information via ENS, delivering a Google-like experience built entirely on decentralized infrastructure.

Image caption: RSS3 search interface Source: RSS3

If on-chain addresses integrate NFT avatars, ENS domains, Twitter accounts, and other platform links, a unified on-chain/off-chain identity system emerges. Already, NFT marketplace OpenSea allows searching accounts and projects directly by ENS (.eth) format.

Total ENS domain registrations have surpassed 2.55 million, with 570,000 users. In September 2022 alone, nearly 400,000 new domains were registered—exceeding July’s 378,800 and setting a monthly record.

Behind ENS’s surge lies the revival of traditional internet domain economics. Speculative strategies include:

Buying domains matching real-world top brands/orgs, hoping for high-price buyouts;

Registering lucky numbers like 666.eth or 888.eth appealing to niche buyers;

Bulk purchasing using PFP NFT investment logic, buying low and selling high during market peaks.

Currently, the most popular ENS domains are four-digit ones (10k Club), with 24-hour sales reaching 1,445 ETH—for example, 7000.eth sold for 170 ETH. Three-digit Arabic domains (Arabic 999 Club) rank second, with 24-hour sales of 95 ETH (e.g., ٠١٠.eth sold for 30 ETH)—these are the shortest allowed ENS domains.

Other categories include five-digit 100K Club domains, Triple Ethmoji emoji domains, and Chinese-number supported 999 Club ENS Chinese domains.

ENS currently has a total market cap of $93 million, but liquidity stands at only 0.78%. Sellers outnumber buyers, and secondary market performance remains weak—still dominated by speculation and hype.

Image caption: ENS ownership data Source: NFTgo.io

This stems from ENS domains being tightly bound to individual users—similar to phone numbers—leading to long-term retention rather than frequent trading.

• TwitterScan: Data Miner Around User Behavior

Developed by MetaScan, TwitterScan aims to extract insights about token prices, NFTs, and new projects from Twitter—the most active public information hub in Web3.

Unlike pure on-chain data paired with DID, TwitterScan relies entirely on Twitter data, maintaining identity alignment with Twitter handles. Its key innovation is applying on-chain data analysis methodologies to traditional Web 2.0 services.

It currently tracks over 17,000 tokens, 150,000 KOLs, and 300+ topics.

This reverse-feeding approach—bringing insights back to Web 2.0—is worthy of deeper study. Many traditional Web 2.0 platforms can become data sources, subject to on-chain recording, identification, and analysis.

Login Tools: Identity Verification and On-Chain Data Accumulation

From a narrow login functionality standpoint, login tools have distinct uses. In Web 2.0, the most common examples are MFA tools like Microsoft Authenticator and Google Authenticator—time-based two-factor authentication widely used for CEX security.

In Web 3.0, tools centered on login and verification are collectively known as login tools.

• Unipass: Unified Login Tool

Built on Nervos CKB, Unipass is a decentralized identity (DID) protocol designed for Web 3.0 users.

Its operation relies on sufficient user adoption to accumulate data, enabling business models around traffic—such as fee structures or institutional services, scalable to both consumer and enterprise markets.

• Bright ID: V-Approved DID Service Integrating 15+ Apps

During Gitcoin’s seventh grant round, BrightID received notable donations and earned praise from Vitalik Buterin. A profitable consulting business could be built around integrating BrightID into apps, reinvesting part of its profits back into BrightID—meaning BrightID’s value depends on the number of integrated applications.

BrightID proposes selling a “sponsorship” for $1 per person. The sponsoring app pays a $1 lifetime fee per user, reinforcing its role as the user’s “first touchpoint.”

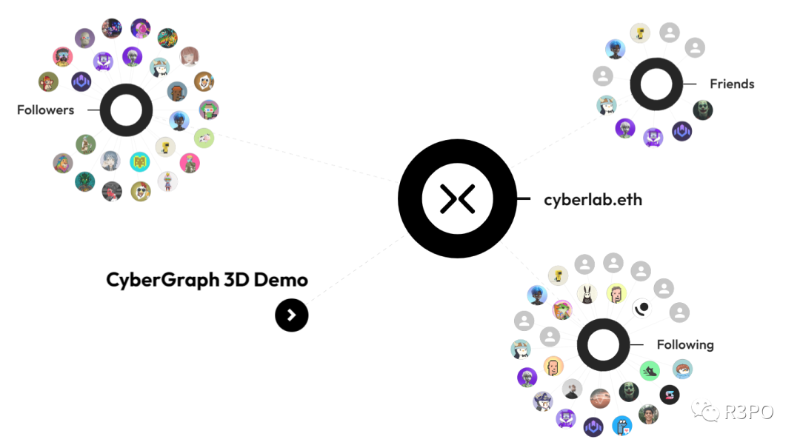

• CyberConnect: WalletConnect’s DID Upgrade

Image caption: CyberConnect operation model Source: cyberconnect

More precisely, CyberConnect is a “meta” DID. Similar to how WalletConnect provides wallet integration, CyberConnect adopts a similar philosophy—continuously incorporating new DIDs, projects, and blockchains to deliver the most seamless login experience.

CyberConnect aims to return ownership of social graph data to users and embed identity systems throughout the entire application lifecycle.

Its user base has surged recently—growing from around 400,000 in January to over 1.5 million by October. Twenty-four organizations including Binance and Protocol Labs are deeply involved, along with 35 ecosystem applications such as SpaceID, NFTGo, helloword, and ZKlink.

Reputation Systems: The Most Relevant Use Case for DID and On-Chain Data

We place this section at the end as a backend example of DID and on-chain data. Previous applications follow a DID-first model—user behavior data comes afterward. Reputation systems invert this logic: sufficient data must first accumulate before assigning users a credibility “score.” This score can serve as a unique SBT identifier, a recovery code for social login, or even the holy grail of DeFi lending—unsecured loans akin to a “Zhima Credit Score.”

• POAP: The True Beginning of Reputation Systems

POAP introduces a reliable way to record on-chain experiences. Each event attendance earns collectors a unique badge backed by on-chain data. POAP badges are non-fungible tokens (NFTs), documenting every step of a user’s journey on-chain.

Organizers can create events on the POAP platform, customizing designs and offerings for attendees. Users scan QR codes at POAP-sponsored events to collect badges. Once a community issues a POAP, the association becomes permanently recorded for both parties.

If social connections are bidirectional and high-frequency, POAP represents proof of person-event linkage—once participated, forever valid.

Major brands and events like the U.S. Open Golf Championship, Lollapalooza, Adidas, and Budweiser have partnered with POAP. By May 2022, over 4.5 million POAPs had been issued to more than 500,000 collectors.

Essentially, like Lens Protocol, POAP acts as a modular component callable by other services. Any project can build its reputation system atop POAP. As data accumulates, individual on-chain histories become rich enough that each POAP effectively fulfills DID functions.

• Galxe (formerly Project Galaxy): A “Pseudo” Decentralized Identity Rating System

Galxe uses KYC services to verify personal identity, then records verified identities on-chain for recognition.

Current approaches either repeatedly verify on-chain behaviors (like Nansen’s Smart Money tracking) or rely on front-end KYC to ensure data authenticity as the basis for identifying on-chain actions.

Its product suite includes services for Binance’s SBT project BAB and an all-in-one Web3 Passport, but it cannot escape criticism regarding the origin of its identity system.

Currently supporting over seven major public chains, partnering with 1,223 projects, and serving 8 million registered users, Galxe is arguably the richest DID data provider in Web3.

Mainstream DeFi apps like Yearn, public chains like BNB and ETH, and platforms like CyberConnect all integrate with Galxe.

However, just as KYC is not a decentralized method, Galxe’s actual operational mechanism contradicts its claimed decentralization—its biggest point of criticism.

Conclusion

From a user experience perspective, DID is the true starting point of Web 3.0—not underlying protocols like oracles or public chains. DID defines the identity of the entrant;

DID should be a feature or module embedded within products—not a standalone product. Wallets, emails, social media, login tools, and authenticators can all incorporate DID functionality;

DID connects all Web 3.0 scenarios as an identity anchor. DEX replacing CEX, ENS replacing traditional domains—

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News