Madman or Genius? The 10-Year Rollercoaster of Two Crypto Maniacs

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Madman or Genius? The 10-Year Rollercoaster of Two Crypto Maniacs

Everyone trusted those two guys from 3AC—they knew what they were doing, right?

By Jen Wieczner

Translated by Amber, Foresight News

The vessel is stunning: a 500-ton, 171-foot hull built of glass and steel, pristine white like the cliffs of Santorini, complete with a swimming pool featuring a glass bottom. Set for completion in July, it promises sunset dinners off Sicily and cocktails over turquoise shallows along Ibiza’s coast—the perfect setting. The prospective captain showed photos of his $50 million yacht to friends at a party, boasting it was “bigger than all the yachts of Singapore’s richest billionaires combined,” and describing plans to outfit guest cabins with projector screens so they could better display their collected NFT art.

Priced at $150 million, this superyacht is the largest ever sold by established shipbuilder San Lorenzo in Asia—an extravagant celebration for crypto “new money.” “This marks the beginning of a fascinating journey,” said the yacht broker in last year’s auction announcement, expressing hopes to “witness many joyful moments aboard.” The buyers even picked a name fitting both crypto culture and humor: Much Wow.

The purchasers, Su Zhu and Kyle Davies, are two Andover-educated graduates running Three Arrows Capital (3AC), a Singapore-based crypto hedge fund. But they never got to pop champagne on the bow of Much Wow. Instead, in July—just as the boat was about to be launched—the pair filed for bankruptcy and vanished before making the final payment, leaving the yacht “stranded” at its berth in La Spezia, Italy. Though not yet officially listed for resale, whispers of the luxury vessel have already circulated among international superyacht dealers.

Since then, the yacht has become an endless meme and cocktail-party gossip on Twitter. From millions of small crypto holders to industry insiders and investors, nearly everyone has watched in shock or dismay as Three Arrows Capital—the once possibly most revered investment fund in the booming global financial sector—collapsed. The firm’s implosion triggered a chain reaction that forced historic sell-offs of Bitcoin and “wiped out” much of the crypto industry’s gains over the past two years.

Multiple crypto firms in New York and Singapore were direct victims of 3AC’s collapse. Voyager Digital, a publicly traded New York–based cryptocurrency exchange once valued at billions of dollars, filed for bankruptcy protection in July, disclosing that Three Arrows Capital owed it over $650 million. Genesis Global Trading extended $2.3 billion in loans to 3AC. Blockchain.com, an early crypto company offering digital wallets and evolving into a major exchange, had lent 3AC $270 million—still unpaid—and has since laid off a quarter of its staff.

Most astute observers of the cryptocurrency industry believe Three Arrows Capital bears significant responsibility for the 2022 crypto crash, which saw Bitcoin and other digital assets plunge by 70% or more amid market chaos and forced liquidations, wiping out over a trillion dollars in value. Sam Bankman-Fried, CEO of FTX, said, “About 80% of this downturn can probably be attributed to 3AC’s blowup.” Having rescued several bankrupt lenders in recent months, he may know these issues better than anyone. “It wasn’t just that 3AC had problems—they were just bigger than everyone else. And because of that, they gained more trust across the entire crypto ecosystem, leading to far worse consequences.”

For a firm that always portrayed itself as playing only with its own money—“We don’t have any outside investors,” Su Zhu, CEO of 3AC, told Bloomberg in February—the scale of destruction was staggering. By mid-July, creditors had filed claims exceeding $2.8 billion, and that figure likely represents only the tip of the iceberg. From the most prominent lending institutions to wealthy individual investors, everyone in crypto seems to have lent their digital assets to 3AC—even 3AC’s own employees, who deposited their salaries into its proprietary platform to earn interest.

“A lot of people feel betrayed, and some feel embarrassed,” said Alex Svanevik, CEO of blockchain analytics firm Nansen. “They shouldn’t, because many lives could be ruined—many trusted them with their money.”

That money now appears gone, along with the assets of several affiliated funds and portions of capital managed by 3AC across various crypto projects. The true extent of the losses may never be known. For many crypto startups that kept funds with the company, publicly disclosing such relationships risks intensified scrutiny from investors and government regulators. (For this reason, and due to legal complexities as creditors, many who spoke about their experiences with 3AC requested anonymity.)

Meanwhile, the abandoned superyacht stands as a slightly absurd embodiment of the arrogance, greed, and recklessness of the firm’s 35-year-old co-founders. As their hedge fund undergoes chaotic liquidation, Su Zhu and Davies remain in hiding. (Multiple emails sent to them and their lawyers requesting comment went unanswered, except for Davies’ auto-reply stating, “Please note I am currently out of the office.”) For an industry constantly defending itself—where practitioners have spent day one trying to prove it isn’t a scam—Three Arrows Capital seemed to single-handedly validate the skeptics’ arguments.

Su Zhu and Davies are two ambitious young men, exceptionally intelligent and deeply attuned to structural opportunities in digital currency: crypto being a game where virtual wealth is created from thin air and convinced into reality using traditional monetary forms. They insisted these digital fortunes should translate into real-world wealth. They built social media credibility by performing the role of billionaire financial geniuses, converting that influence into actual financial credit, then borrowing billions for speculative investments, amplifying success through their influential platforms. Unbeknownst to many, the pretenders grew into genuine billionaires capable of buying superyachts. They navigated by instinct, seemingly making every plan work perfectly—until doom arrived suddenly.

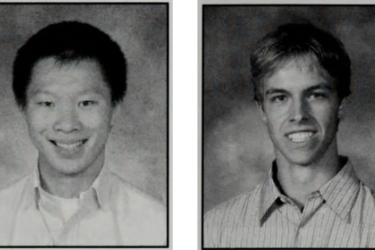

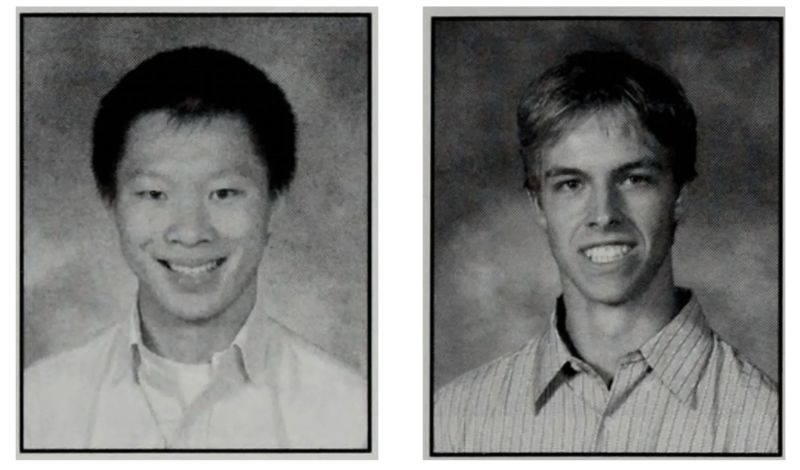

Su Zhu and Davies in their senior year at Andover in 2005. Source: Phillips Academy

Su Zhu and Kyle Davies met at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts—a school known for students from immense wealth or prestigious families—but both grew up in relatively modest environments in Boston’s suburbs. “Our parents weren’t rich,” Davies said in a recent interview. “We were very middle-class.” They weren’t especially popular either. “They were called nerds, especially Su,” one classmate said. “Actually, they weren’t odd at all—just shy.”

Su Zhu, a Chinese immigrant who came to the U.S. at age six, was known for perfect GPAs and rigorous AP courses; in his senior yearbook, he received the top honor of “Most Diligent”. He won special awards for math but wasn’t just a numbers person—he also received Andover’s highest fiction prize upon graduation. “Su was the smartest in our class,” recalled a classmate.

Davies was also a star on campus, though otherwise seen as an outsider—if remembered at all. An aspiring Japanophile, Davies earned top honors in Japanese at graduation. According to Davies, he and Su Zhu weren’t particularly close back then. “We went to high school together, college together, found our first jobs together,” he said on a 2021 crypto podcast. “We weren’t best friends. I didn’t really know him in high school. I knew he was smart—he was our class valedictorian—but in college we interacted more.”

“College together” meant Columbia University, where both took math-heavy courses and joined the squash team. Su Zhu graduated a year early with honors, then moved to Tokyo to work in derivatives trading at Credit Suisse, with Davies interning alongside him. Their desks sat side by side until Su Zhu was laid off during the financial crisis and later joined Flow Traders, a high-frequency trading platform in Singapore.

There, Su Zhu learned the art of arbitrage—capturing tiny shifts in relative value between two related assets, typically selling overpriced ones and buying underpriced ones. He focused on exchange-traded funds (ETFs)—essentially mutual funds listed like stocks—trading related funds for slim profits. He excelled, ranking near the top in profitability at Flow. This success boosted his confidence. He became known for openly criticizing colleagues’ performance, even calling out his boss. Su Zhu stood out in another way: Flow’s office, packed with servers, was hot, and he’d show up in shorts and T-shirts, often stripping down shirtless, even walking through hallways without re-dressing. “Su would walk around bare-chested in his tiny shorts,” recalled a former colleague. “He was the only trader who’d take off his shirt.”

After Flow, Su Zhu briefly worked at Deutsche Bank, following in the footsteps of crypto legend and BitMEX co-founder Arthur Hayes. Davies stayed at Credit Suisse, but both were already tired of big banks. Su Zhu complained to acquaintances about low-caliber bank colleagues losing company money with no consequences. In his view, the best talent had already left hedge funds—or gone independent. He and Davies, then 24, decided to launch their own platform. “Leaving had almost no downside,” Davies explained in a recent interview. “Like, if we left and completely failed, we’d still get another job for sure.”

In 2012, Su Zhu and Davies temporarily lived in San Francisco, pooling savings and borrowing from parents to raise about $1 million in seed funding for Three Arrows Capital. The name came from a Japanese fable where a great daimyo or warlord teaches his sons the difference between breaking one arrow easily and failing to break three bound together.

On the podcast UpOnly, Davies said their money doubled in less than two months. They quickly moved to Singapore, a jurisdiction with no capital gains tax, registering the fund there by 2013 and planning to renounce their U.S. citizenship. Su Zhu, fluent in Mandarin and English, navigated Singapore’s social circles smoothly, occasionally hosting poker games and friendly matches with Davies. Still, they seemed frustrated that Three Arrows Capital couldn’t reach the next level. At a dinner around 2015, Davies lamented to another trader how hard it was to raise funds from investors. The trader wasn’t surprised—after all, Su Zhu and Davies lacked pedigree and track record.

In this early phase, Three Arrows Capital focused on a niche: arbitraging emerging-market foreign exchange (or “FX”) derivatives—financial products tied to future prices of smaller currencies (like the Thai baht or Indonesian rupiah). BitMEX’s Hayes recently wrote on Medium that access to these markets depended on strong trading relationships with big banks, making entry “almost impossible.” “When Su and Kyle told me how they started, I was impressed by how quickly they entered this lucrative space.”

At the time, FX trading was shifting to electronic platforms, making it easy to spot pricing discrepancies or spreads between different banks. Three Arrows Capital positioned itself perfectly to “pick off” these mispricings, as Wall Street calls it, usually earning cents per dollar traded. It was a strategy banks hated—Su Zhu and Davies were essentially siphoning profits institutions would’ve kept. Sometimes, when banks realized they’d mispriced quotes to 3AC, they’d demand to reverse or cancel trades, but Su Zhu and Davies wouldn’t budge. Last year, Su Zhu tweeted a photo from 2012 of himself smiling at 11 screens. Seemingly referencing their FX strategy of picking off bank quotes, he wrote, “You haven’t lived until you’ve beaten five traders at 2:30 a.m. on identical quotes.”

By 2017, banks began trying to block such arbitrage. “Whenever Three Arrows Capital asked for a quote, every bank FX trader would say, ‘Fuck these guys, I’m not pricing for them,’” said a former trader who once faced 3AC. Recently, a joke circulated among FX traders: they knew 3AC very early and now, watching it collapse, felt somewhat vindicated. “We FX traders bear some blame because we knew these guys couldn’t make money in FX,” the former trader said. “But when they entered crypto, everyone thought they were geniuses.”

On May 5, 2021, at the peak of Three Arrows Capital’s wealth, Su Zhu tweeted a photo from 2012 showing him and Davies trading from a two-bedroom apartment. The message was implicit: imagine building a multi-billion-dollar company from such humble beginnings. Source: Su Zhu’s Twitter

A fundamental thing to understand about cryptocurrency is that, so far, it has proceeded through extreme but roughly regular boom-and-bust cycles. In Bitcoin’s 13-year history, the 2018 bear market was particularly painful. After hitting a record high of $20,000 at the end of 2017, the cryptocurrency plunged to $3,000, taking down thousands of smaller tokens along the way. It was against this backdrop that Three Arrows Capital turned its attention to crypto—timing its entry so perfectly that Su Zhu was frequently hailed as a genius (i.e., credited) for pinpointing the cycle’s bottom. In later years, to many impressionable crypto newcomers—and even industry insiders—following Su Zhu and Davies on Twitter, it looked like brilliance. But in reality, that timing might have simply been luck.

With cryptocurrencies trading on exchanges worldwide, the firm’s arbitrage expertise immediately paid off. A famous strategy involved the “kimchi premium”—buying Bitcoin in the U.S. or China and selling it at a higher price in South Korea, where tighter exchange regulations led to inflated prices. Back then, such profitable trades were abundant. They became 3AC’s bread and butter, allowing the fund to tell investors it employed low-risk strategies designed to profit in both bull and bear markets.

Another form of crypto arbitrage might involve buying Bitcoin at the current (“spot”) price while selling Bitcoin futures, or vice versa, to capture price premiums. “The fund’s investment objective is to achieve consistent market-neutral returns while preserving capital,” stated 3AC’s official documents. Of course, investing with limited downside regardless of market direction is called “hedging”—hence “hedge fund.” But hedging strategies tend to drain the most capital when scaled up, so Three Arrows Capital began borrowing funds to deploy. If all went well, the profits generated could exceed loan interest. Then they’d do it again, expanding their investment pool to borrow even larger sums.

Beyond heavy borrowing, the firm’s growth strategy relied on another plan: building massive social media influence for the two founders. In crypto, the only important social media platform is Twitter. Many key figures in this global industry are anonymous or pseudonymous accounts with silly cartoon avatars. In this unregulated space with no traditional institutions and 24/7 global market action, Crypto Twitter is the arena’s center—a hub for market-moving news and opinions.

Su Zhu earned entry into the upper echelons of Crypto Twitter. Friends say Su Zhu had a clear plan to become a “Twitter celebrity”: post constantly, cater to the crypto masses with extremely optimistic predictions, attract massive followings, and ultimately become a top predator on Crypto Twitter—profiting at the expense of everyone else.

Su Zhu amassed 570,000 followers by promoting his “supercycle” theory—the idea of a multi-year Bitcoin bull run pushing prices to millions per coin. “As the crypto supercycle continues, more and more people will try to figure out how early they are,” Su Zhu tweeted last year. “The only thing that matters is how many coins you have right now.” And: “As the supercycle continues, mainstream media will talk about how early whales owned everything. The richest in crypto had net worths near zero in 2019. I know someone sarcastically said, if someone had borrowed them $50,000 more back then, they’d have $500 million more now.” Su Zhu repeated this mantra across platforms, podcasts, and video shows: buy, buy, buy now—the supercycle will make you rich someday.

“They used to boast about borrowing as much as they wanted,” said a former trader who knew them in Singapore. “It was all planned, man—from how they built credibility to how the fund was structured.”

As it grew, Three Arrows Capital expanded beyond Bitcoin into a range of startup crypto projects and more obscure cryptocurrencies (sometimes called “shitcoins”). The firm seemed indiscriminate in these bets, almost treating them like donations. Earlier this year, Davies tweeted: “What venture capital invests in doesn’t matter—more fiat in the system benefits the industry.”

Many investors recall first sensing something might be wrong with Three Arrows Capital in 2019. That year, the fund approached peers in the industry touting a rare opportunity. 3AC invested in Deribit, a crypto options exchange, then offered to sell part of its stake; the term sheet valued Deribit at $700 million. But some investors noticed the valuation seemed off—and discovered its actual valuation was only $280 million. It turned out 3AC was trying to sell its stake at a steep markup, effectively generating a huge kickback for the fund. In venture capital, this is a serious breach, blinding both outside investors and Deribit itself.

But the firm was thriving. During the pandemic, with the Fed injecting money into the economy, the crypto market rose for months. By the end of 2020, Bitcoin had quintupled from its March lows. To many, it truly looked like a supercycle was underway. According to its annual report, Three Arrows Capital’s flagship fund returned over 5,900%. By year-end, it managed over $2.6 billion in assets and $1.9 billion in liabilities.

One of 3AC’s largest positions—and a pivotal one in its fate—was a stock-exchange-traded form of Bitcoin called GBTC (short for Grayscale Bitcoin Trust). The company abandoned its old arbitrage playbook, accumulating up to $2 billion in GBTC. At the time, it traded at a premium to regular Bitcoin, and 3AC happily pocketed the spread. On Twitter, Su Zhu frequently expressed bullish views on GBTC, repeatedly noting that buying it was “smart” or “clever.”

Su Zhu and Davies’ public personas grew increasingly extreme; their tweets more flamboyant, and acquaintances say they openly condescended toward old friends and less wealthy peers. “They have little empathy for most people, especially ordinary folks,” said a former friend.

Three Arrows Capital was notorious for high employee turnover, especially among traders, who complained they never got credit for winning trades but were berated as stupid when they failed—even having salaries withheld and bonuses cut. (Still, 3AC traders were highly sought after in the industry; before the fund collapsed, Steve Cohen’s hedge fund Point72 was interviewing a team of 3AC traders to quietly poach its trading staff.)

Su Zhu and Davies kept internal operations secret. Only the two of them could transfer funds between certain crypto wallets; most 3AC employees didn’t know how much money the company managed. While employees complained about long hours, Su Zhu resisted hiring new staff, fearing they’d “leak trade secrets.” In Su Zhu’s view, Three Arrows Capital was doing workers a favor. “Su said they should be paid for providing valuable learning opportunities to employees,” added the friend. Some business associates in Singapore described the 3AC founders as playing roles straight out of a 1980s Wall Street trading pit.

Now married fathers with young children, they became fitness fanatics, working out up to six times a week and restricting calories. Su Zhu reduced his body fat to around 11%, posting shirtless “updates” on Twitter. A friend recalled that at least once, he called his personal trainer “fat.” When asked about his drive to become a “big shot,” Su Zhu told an interviewer, “Most of my life I was very weak. After COVID, I got a personal trainer. I have two kids, so it’s wake up, play with your kids, go to work, go to the gym, come home, put them to sleep.”

Though not yet billionaires, Su Zhu and Davies began enjoying some luxuries of the ultra-rich. In September 2020, Su Zhu bought a $20 million mansion in Singapore under his wife’s name, known locally as a “good-class bungalow.” The next year, he purchased another property for $35 million under his daughter’s name. (Davies, after becoming a Singapore citizen, also bought a luxury home, though renovations weren’t complete and he hadn’t moved in.)

Yet personally, Su Zhu remained introverted, disliking small talk. Davies was outspoken in business deals and social events. Some acquaintances who first met the pair on Twitter found them surprisingly low-key in person. “He’s very dismissive of many mainstream, popular things,” said a friend of Davies. After getting rich, Davies went to great lengths to buy and customize a Toyota Century—a deceptively simple-looking car priced similarly to a Lamborghini. “He takes pride in that,” another friend said.

While Su Zhu and Davies gradually adjusted to their new wealth, Three Arrows Capital remained a massive funnel for borrowed funds. A lending frenzy swept the crypto industry as DeFi (“decentralized finance”) projects offered depositors interest rates far above traditional banks. Three Arrows Capital held crypto assets belonging to employees, friends, and other wealthy individuals via its platform. When lenders demanded collateral from 3AC, it was often refused. Instead, it offered 10% or higher interest—above any competitor. As one trader put it, due to its “gold standard” reputation, some lenders didn’t even request audited financial statements or documentation. Even with massive size and apparent capital strength,

For other investors, Three Arrows Capital’s hunger for cash was another red flag. In early 2021, Warbler Capital—a fund managed by a 29-year-old Chicago native—tried raising $20 million to implement a strategy largely outsourcing capital to 3AC. Matt Walsh, co-founder of crypto-focused Castle Island Ventures, couldn’t understand why a multi-billion-dollar fund like Three Arrows Capital would bother with such a small sum. “I was sitting there baffled,” Walsh recalled. “It started ringing alarm bells. Maybe these institutions were already insolvent.”

Trouble seemed to begin last year, with 3AC’s massive bet on GBTC at the heart of the problem. Just as the firm profited when GBTC traded at a premium, it suffered when GBTC began trading below Bitcoin’s price. GBTC’s premium stemmed from its initial uniqueness—it allowed owning Bitcoin in your eTrade account without dealing with crypto exchanges and arcane wallets. As more people entered the space and new alternatives emerged, the premium vanished—then turned negative. But many sharp market participants saw this coming. “All arbitrage eventually disappears,” said a trader and former colleague of Su Zhu.

Davies recognized the risk this posed to 3AC. On a September 2020 episode of a podcast produced by Castle Island, he admitted he expected this position to lose money. But before airing, Davies requested the clip be removed. 3AC’s GBTC shares were locked for six months—though Su Zhu and Davies had a chance to exit around that fall, they didn’t.

“They had plenty of chances to escape,” Fauchier said. “I don’t think they’d be dumb enough to do this with their own money. I don’t know what gripped their minds. Clearly, this is one trade you want to be first into—and not last out.” Colleagues now say 3AC held onto its GBTC position betting the SEC would approve GBTC’s long-awaited ETF conversion, making it more liquid and tradable and potentially eliminating the Bitcoin price mismatch. (In June, the SEC rejected GBTC’s application.)

By spring 2021, GBTC had fallen below Bitcoin’s price, severely hurting 3AC. Yet, crypto continued its bull run into April, with Bitcoin setting records above $60,000 and Dogecoin soaring amid Elon Musk-fueled irrational exuberance. Su Zhu was bullish on Dogecoin too, with reports citing Nansen saying 3AC’s assets were around $10 billion at the time (though Nansen’s CEO now clarifies most of that was likely borrowed).

Looking back, Three Arrows Capital seems to have suffered a fatal blow—human rather than financial—later that summer. In August, two minority partners at the fund, based in Hong Kong and working 80 to 100 hours weekly managing most of 3AC’s operations, retired simultaneously. This left most responsibilities to Three Arrows Capital’s chief risk officer, Davies, who appeared to take a more relaxed approach to identifying corporate vulnerabilities. “I think their risk management used to be much better,” said the former friend.

Around that time, signs emerged that Three Arrows Capital faced a cash crunch. When lenders demanded collateral for the fund’s margin trading, it typically pledged equity in the private company Deribit rather than liquid assets like Bitcoin. Such illiquid assets aren’t ideal collateral. But another issue arose: 3AC co-owned Deribit shares with other investors who refused to sign agreements allowing their stakes to be used as collateral. Clearly, 3AC was trying to pledge assets it had no right to—and tried repeatedly, offering the same shares to multiple institutions, especially after Bitcoin began falling in late 2021. The firm seemed to have pledged the same locked-up GBTC to several lenders. FTX CEO Bankman-Fried said: “We suspect Three Arrows Capital tried to pledge some collateral to multiple parties simultaneously.” “If that were the only misrepresentation here, I’d be very surprised—that’d be a strange coincidence. I strongly suspect they did more.”

Crypto bear markets often dwarf volatility in any traditional financial market. The crashes are so severe insiders call them “crypto winters,” and these downturns can last years. This was the situation Three Arrows Capital found itself in by mid-January 2022—unable to hold on. Its GBTC position was creating an ever-larger hole on 3AC’s balance sheet, while most of its capital was tied up in restricted stock of smaller crypto projects. Other arbitrage opportunities had dried up. In response, Three Arrows Capital appears to have decided to increase investment riskiness, hoping for a big win to stabilize the company. “All that changed was excessive pursuit of returns,” said a senior lending executive. “They might’ve said, ‘What if we go long?’”

In February this year, Three Arrows made its biggest gamble yet: investing $200 million in Luna, a trendy token created by Do Kwon, a charismatic, arrogant Korean developer and Stanford dropout.

Around the same time, Su Zhu and Davies were planning to leave Singapore. They had already moved part of the fund’s legal infrastructure to the British Virgin Islands, and in April, Three Arrows Capital announced relocating its headquarters to Dubai. Friends say that month, Su Zhu and Davies bought two villas totaling about $30 million—one on Crystal Lagoons in Dubai’s District One, an artificial aquamarine oasis larger than anywhere else on Earth. Sharing photos of the side-by-side mansions, Su Zhu told friends he’d bought his new seven-bedroom estate from the consul—a 17,000-square-foot compound.

But in early May, Luna suddenly crashed to nearly zero, vaporizing over $40 billion in market cap within days. Its value was pegged to a related stablecoin called terraUSD. When terraUSD failed to maintain its dollar peg, both currencies collapsed. According to Herbert Sim, a Singapore investor tracking 3AC’s wallets, 3AC’s Luna holdings—once worth about $5 billion—“vanished overnight,” triggering a death spiral.

Scott Odell, head of lending at Blockchain.com, contacted the company to assess the damage. After all, loan agreements stipulated 3AC must notify them if its overall drawdown reached at least 4%. “It wasn’t that large as part of the portfolio anyway,” wrote Edward Zhao, a top 3AC trader, according to public messages from Blockchain.com. Hours later, Odell notified them he needed to reclaim a large portion of its $270 million loan, payable in dollars or stablecoins. This caught them off guard.

The next day, Odell reached Davies directly, who assured him tersely that everything was fine. He sent Blockchain.com a simple, watermark-free one-sentence letter claiming the firm managed $2.387 billion. Meanwhile, Three Arrows Capital made similar statements to at least six lenders. According to affidavits in a 1,157-page document released by 3AC’s liquidators, Blockchain.com “now doubts the accuracy of this net asset value statement.”

Days later, rather than backing down, Davies threatened to “blacklist” Blockchain.com if it reclaimed 3AC’s loan. “Once that happened, we knew something was wrong,” said Lane Kasselman, chief commercial officer at Blockchain.com.

Inside Three Arrows Capital, the atmosphere shifted.

According to a former employee, Su Zhu and Davies used to hold regular Zoom presentations, but that month they stopped appearing, and managers eventually canceled these meetings altogether.

In late May, Su Zhu posted a tweet that might as well be his epitaph: “The supercycle price argument was wrong, unfortunately.” Still, he and Davies acted calm, seemingly reaching out to every wealthy crypto investor they knew, asking to borrow large amounts of Bitcoin at the same high interest rates the company always offered. “Clearly, even after knowing they were in trouble, they were still boosting their image as a powerful crypto hedge fund,” said someone close to one of the largest lenders. In practice, Three Arrows Capital was merely seeking funds to repay other lenders. “It’s robbing Peter to pay Paul,” said Matt Walsh. In mid-June, a month after Luna’s collapse, Davies told Blockchain.com’s chief strategy officer Charles McGarraugh he was trying to find another lender to avoid liquidating his positions.

But in practice, such financial chaos often triggers mass sell-offs by all involved to raise cash and stay solvent. 3AC’s positions were so large that it began impacting the broader crypto market: 3AC itself and other panicked investors scrambled to sell and meet margin calls, further driving prices down in a vicious cycle. As lenders demanded more collateral and sold positions when 3AC and others couldn’t deliver, Bitcoin and its peers fell to multi-year lows, fueling further declines. With the total crypto market value plunging from a late-2021 peak of $3 trillion to under $1 trillion, the crash made global headlines. McGarraugh said Davies told him, “If the crypto market keeps falling, 3AC has no chance.” That was the last time anyone at Blockchain.com spoke to Davies. After that, he and Su Zhu stopped answering lenders, partners, and friends.

Rumors of the company’s collapse spread rapidly on Twitter, further accelerating broader crypto sell-offs. On June 14, Su Zhu finally acknowledged the issue: “We are communicating with relevant parties and fully committed to resolving this,” he tweeted. Days later, Davies spoke to The Wall Street Journal, saying he and Su Zhu remained “believers in crypto,” but admitted, “Terra-Luna caught us completely off guard.”

Su Zhu began trying to sell at least one of his luxury properties. Meanwhile, the company started moving funds. On June 14—the same day Su Zhu tweeted—3AC sent nearly $32 million in stablecoins to a crypto wallet belonging to a shell subsidiary in the Cayman Islands. “It’s unclear where these funds went afterward,” wrote the liquidators in their affidavits. But there’s a working theory. In 3AC’s final days, partners reached out to every wealthy crypto whale they knew, borrowing more Bitcoin, and top crypto executives and investors—from the U.S. to the Caribbean to Europe to Singapore—believe 3AC found willing final lenders among organized crime figures. Owing a large sum to such figures could explain why Su Zhu and Davies went into hiding. These are also the kind of lenders you’d want to repay before anyone else, but you might need to route funds through the Cayman Islands. Said a former trader and 3AC business partner, “They paid back the mafia,” adding, “If you start borrowing from these people, you’re definitely desperate.”

After the collapse, exchange executives began tracing the digital breadcrumbs left behind. They were stunned to discover Three Arrows Capital held absolutely no short positions—meaning it had stopped hedging, the core of its original investment strategy. “It’s easy to do,” said a senior lending executive. “No trading desk knows you’re doing it.” Investors and exchange executives now estimate that by year-end, 3AC was leveraged about three times its assets, with some suspecting the number could be higher.

Three Arrows Capital appears to have pooled all money into mixed accounts—whose owners were unaware—taking bits from each to repay lenders. “They might’ve managed the whole thing on Excel spreadsheets,” said Walsh. This means when 3AC ignored margin calls in mid-June and hid information from lenders, those lenders—including FTX and Genesis—liquidated their accounts, unknowingly selling assets belonging to 3AC partners and clients.

After traders stopped responding, lenders tried calling, emailing, and messaging them on every platform, even contacting friends and visiting their homes before liquidating collateral. Some peered through 3AC’s Singapore office door, where mail had piled up for weeks. Just weeks earlier, those who considered Su Zhu and Davies close friends and lent them money (even $200,000 or more) heard nothing about the fund’s troubles and now felt angry and betrayed. “They’re definitely sociopaths,” said a former friend. “The numbers they reported in May were wildly inaccurate,” said Kasselman. “We firmly believe they committed fraud. There’s no other explanation—that’s fraud, they lied.” Genesis Global Trading, which lent 3AC the most among all lenders, has filed claims totaling up to $1.2 billion. Others lent them billions more, mostly in Bitcoin and Ethereum. So far, liquidators have recovered only $40 million in assets. “Clearly, they were insolvent but kept borrowing—that looks exactly like a classic Ponzi scheme,” said Kasselman. “Comparisons to Bernie Madoff aren’t far off.”

When Three Arrows Capital filed for Chapter 15 bankruptcy in the Southern District of New York on July 1, something curious emerged. Even as creditors rushed to file claims, the 3AC founders had already moved first: topping the claims list was Su Zhu himself, filing a $5 million claim on June 26, and Davies’ wife Kelly Kaili Chen, claiming she lent the fund nearly $66 million. Yet their claims lacked any evidence beyond a number. “It’s a complete joke,” said Walsh. Though insiders didn’t know Chen was involved, they assumed she was acting for Davies; her name appeared on various corporate entities, likely for tax reasons.知情人士透露,Su Zhu的母亲和Davies的母亲也提出了索赔。(Su Zhu后来告诉彭博社,“你知道,他们会说我在上一段时期潜逃了资金,实际上我把更多的个人资金投入了。”)

According to sources, since the company filed for bankruptcy, liquidators have not contacted Su Zhu and Davies as of publication and still don’t know their whereabouts. Their lawyers say the co-founders have received death threats. In an awkward Zoom meeting on July 8, participants using Su Zhu and Davies’ usernames logged in with cameras off and refused to unmute, even as BVI liquidators posed dozens of questions to their avatars.

Regulators are also scrutinizing Three Arrows Capital. The Monetary Authority of Singapore—the country’s equivalent of the SEC—is investigating whether 3AC “seriously breached” its rules; the agency has already sanctioned the firm for providing “false or misleading” information.

On July 21, Su Zhu and Davies gave an interview to Bloomberg “from a secret location.” This interview was unusual for several reasons—Su Zhu protested headlines about his free-spending lifestyle by citing biking to work, avoiding nightclubs, and having “only two homes in Singapore”—and blamed 3AC’s collapse on their failure to anticipate the crypto market might fall. Neither mentioned the word “supercycle,” but the attitude was clear. As Davies put it, “We did very well in good times. We just lost the most in the bad phase.”

The two also told Bloomberg they planned to go to Dubai “soon.” Friends say they’re already there. Lawyers say the desert oasis offers a particular advantage: the country has no extradition treaty with Singapore or the U.S.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News