The Merits and Flaws of CeFi from a Liquidity Perspective

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Merits and Flaws of CeFi from a Liquidity Perspective

Where there is finance, there will always be risk.

Author: Solv Research Group

[Note] This article is the third in-depth analysis by the Solv Research Group on the recent crypto market crash. Building upon the previous discussion about dollarization in the crypto market, it focuses on how centralized financial (CeFi) institutions have effectively functioned as banks—providing liquidity, leverage management, and maturity transformation services to the industry—while also examining their shortcomings and root causes.

TL;DR

After dollarization of the crypto market, liquidity (in the form of USD stablecoins) is primarily supplied externally to support investment, speculation, and operational needs within the ecosystem. During the 2017–2018 ICO era, fundraising in the crypto industry was mainly conducted through direct equity investments, which suffered from high volatility, significant moral hazard, and led to widespread fraud.

Since 2020, the crypto industry has seen a surge in debt-based financing alongside equity financing, creating a mixed landscape of direct and indirect investment. As such, the industry now requires institutions akin to banks to deliver four critical functions:

First, create liquidity;

Second, provide credit to help productive sectors leverage while managing leverage risks;

Third, perform maturity transformation, manage term risk, and enable necessary risk isolation;

Fourth, optimize capital allocation.

Delivering these functions requires robust credit risk management capabilities. However, at current technological and infrastructural levels, DeFi lacks any credit mechanism entirely. Nearly all DeFi protocols algorithmically offload risk entirely onto users without assuming any themselves—an approach that underpins DeFi’s success but also defines its limitations.

Over the past two years, centralized financial institutions (CeFi) in the crypto space have effectively served as banking systems, taking on risk and delivering the above services to the broader market. Yet due to widespread lack of expertise and experience, they made several critical mistakes in risk management, including:

-

Arbitrary, unregulated, and opaque lending practices;

-

Procyclical aggressive leveraging, exposing massive risk exposure;

-

Mixed operations with unrestricted use of funds for high-risk speculative trading.

Now, many people attribute the entire collapse solely to the greed and stupidity of certain CeFi institutions—a convenient narrative, yet ultimately meaningless. The root cause lies instead in the immaturity of the crypto industry during its early development phase: no reputation-based credit system exists; blockchain advantages haven't been fully leveraged to establish disclosure and behavioral oversight mechanisms for centralized institutions; and foundational infrastructure like fixed-term DeFi lending or inter-institutional repo markets remains undeveloped. Consequently, when the bear market hit, CeFi institutions collapsed en masse—not mitigating or isolating systemic risk, but amplifying the crisis.

The crypto industry must first clearly recognize these structural issues, then build industry-wide collaborative frameworks, using mechanisms like SBTs to explicitly introduce reputation, creditworthiness, and term-dated financial products on-chain. It should actively develop inter-institutional lending and repo markets, establishing a money market distinct from secondary trading. Only then can the crypto industry enter a more stable and healthy growth trajectory, enabling broad-scale advancement of Web3 and blockchain applications.

[Main Text]

The 2022 crypto bear market occurred against the backdrop of an increasingly dollarized crypto economy.

If allocating responsibility, two-thirds stem from external macroeconomic monetary policy shifts, and one-third from internal industry flaws.

However, for the long-term development of crypto, it's precisely this one-third of internal problems that require deep reflection and reform.

Let us begin with USD stablecoins.

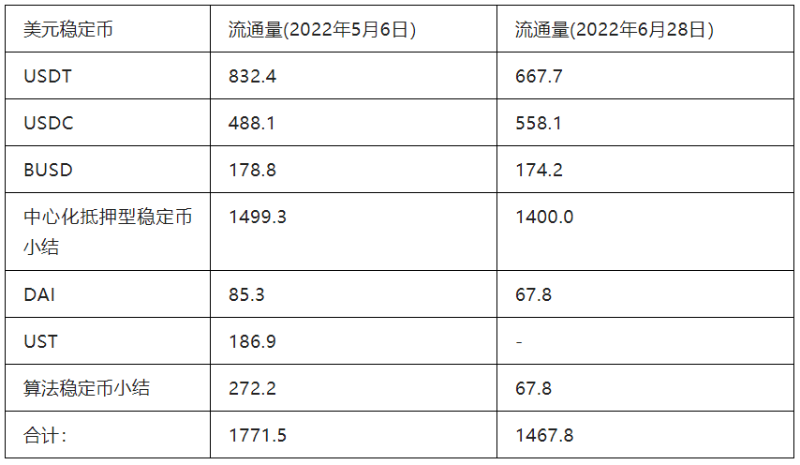

On May 6, 2022—before the full-scale Terra crisis erupted—the circulating supply of major USD stablecoins stood at:

Unit: hundred million USD

Figure 1. Circulating Supply of Major USD Stablecoins Before and After Terra Collapse

As shown, the sharp decline between May and June 2022 reduced overall crypto market liquidity by 17.1%, of which 10.6 percentage points stemmed directly from the Terra collapse. Undoubtedly, this represents a severe contraction in liquidity and is the immediate driver behind the onset of the bear market.

How did these USD stablecoins enter the crypto economy? Who created them, and through what mechanisms?

1. The Supply-Demand Imbalance in USD Stablecoin Liquidity

During the 2017–2018 ICO period, fundraising in the crypto industry was dominated by direct equity investments, characterized by extreme volatility, high risk, and rampant fraud. Individual investors lacked professional financial knowledge, risk management skills, maturity transformation capabilities, and thorough project evaluation abilities, making them highly susceptible to herd mentality. Their liquidity provision exhibited strong procyclicality—“buying high, selling low”—amplifying market swings. In bull markets, such capital floods in, creating excess liquidity and enabling low-quality projects to thrive. In downturns, capital flees rapidly, accelerating liquidity contraction and price declines, often leading to sudden market collapses. Moreover, since equity investments involve shared risk between investors and projects, moral hazard is extremely high, facilitating fraud. Practically speaking, retail investor crowds often display “adverse selection,” consistently picking the most fraudulent projects, resulting in a capital allocation process where劣币驱逐良币 (bad drives out good). Thus, after the 2018 ICO bubble burst, the industry largely abandoned this funding model.

After 2020, lending platforms and protocols surged in popularity, ushering in a dual regime of debt and equity financing, as well as direct and indirect investment. Instead of investing stablecoins directly into projects, many users began channeling funds through intermediaries like funds. More individuals opted for debt instruments, making two models dominant in liquidity creation:

First, centralized collateralized stablecoins like USDT, USDC, and BUSD are issued against fiat USD reserves. Prior to the crisis, this category accounted for ~85% of total stablecoins; afterward, its share rose to 95.4%.

Second, algorithmic stablecoins like DAI and UST are over-collateralized using digital assets such as BTC, ETH, and LUNA via platforms like MakerDAO and Terra. These constituted about 15% of total stablecoins pre-crisis, dropping to 4.6% post-crash.

Once debt financing became mainstream, it introduced new challenges for liquidity management in crypto markets. Real value creators and economic actors—projects—have specific capital needs, broadly summarized as follows:

-

First, ample but not excessive capital supply. Sufficient funding supports quality projects, but oversupply enables scams and Ponzi schemes, increasing systemic risk.

-

Second, stable and predictable funding flows insulated from market volatility, allowing teams to plan long-term.

-

Third, diverse tenor options—long-term funding via equity or token sales, medium- to short-term liquidity via collateralized or credit-based loans.

-

Fourth, clear, professional, value-driven evaluation systems to optimize capital allocation, filter out weak projects, and ensure innovative, value-generating initiatives succeed in competitive funding environments.

Yet these needs cannot be met by existing DeFi solutions. Algorithmic stablecoin protocols like Terra and Maker, or lending platforms like Compound and Aave, exhibit strong procyclicality themselves—expanding liquidity when collateral prices rise, and aggressively liquidating positions when prices fall. This behavior, vividly demonstrated by Terra’s real-time implosion over the past year, is now widely understood.

Another less-discussed issue is that current DeFi assumes zero risk, aggressively pushing all risk onto users via algorithms. For instance, almost no DeFi protocol incorporates credit assessment or handles maturity transformation—all are effectively “on-demand” or “checking account” models. When collateral values drop, DeFi stablecoin or lending protocols instantly and mechanically trigger large-scale asset liquidations, dumping sell pressure onto already fragile markets and frequently triggering cascading collapses. This dynamic has played out repeatedly during every major market crash since 2020, acting as a key catalyst turning volatility into full-blown crashes.

The problem is now clear. With dollarization comes widespread debt financing, forming a hybrid system of equity/debt and direct/indirect investment. Therefore, the crypto industry needs bank-like institutions to deliver four essential functions:

-

First, create liquidity;

-

Second, extend credit to help productive sectors leverage while managing leverage risk;

-

Third, conduct maturity transformation, manage duration risk, and implement necessary risk isolation;

-

Fourth, optimize capital allocation.

Which entities played this banking role over the past two years?

2. CeFi as Crypto Banks

The rise of numerous CeFi institutions was another defining feature of the 2020–2022 bull cycle. During the preceding bear market (pre-2020), although some CeFi entities existed, most focused on trading, arbitrage, and other speculative activities. Few engaged in productive investment or lending, and those that did were small in scale. After the 2020 bull run began, CeFi institutions proliferated, growing their managed assets by orders of magnitude and undergoing a fundamental functional shift—effectively becoming the banking system of the crypto economy.

According to the Bank of England, the banking system performs three core functions: money creation, leverage provision, and maturity transformation. Examining the recent bull market closely reveals that CeFi institutions indeed fulfilled these roles. Ironically, the chain of defaults and blowups among CeFi players over the past two months has helped clarify just how central their prior role truly was.

First, USD stablecoin liquidity is primarily created on the balance sheets of CeFi institutions. Most CeFi firms raise capital through proprietary funds and convert those funds into stablecoins. This conversion ultimately occurs on the balance sheets of stablecoin issuers like Tether, Circle, and Binance—but the demand-side initiation and structuring happen within CeFi entities. This method represents the dominant pathway for stablecoin liquidity creation today. Hence, CeFi institutions can rightly be viewed as the de facto money creators of the entire crypto economy.

Second, CeFi institutions extend credit and provide leverage to other sectors. Lending among CeFi players is widespread, with unsecured or partially secured credit lines being common. The recent cascading failures of Three Arrows Capital, Celsius, Voyager, and others revealed just how vast the web of inter-CeFi credit had become. Public reports indicate much of this borrowed capital was funneled into high-risk speculation—the direct cause of their collapse. Nevertheless, it's important to note that CeFi-to-project credit lines—leveraging productive sectors—are also emerging. For example, Solv platform has facilitated nearly $30 million in project-level borrowing, all used to fund actual development work.

Additionally, CeFi institutions perform maturity transformation. When CeFi firms make token-based investments in projects, they are essentially converting short-term or on-demand capital into long-term investments. This "borrow short, lend long" model inherently introduces liquidity risk. But by bearing this risk internally, CeFi institutions provide stable, long-term funding to projects, enabling them to execute multi-year plans. For instance, Three Arrows Capital announced startup investments shortly before its collapse. From the recipient’s perspective, once funds are received, there is no obligation to return them even if the investor later goes bankrupt. The project can continue development uninterrupted. In this sense, Three Arrows transformed its own short-term liabilities into long-term capital for others, acting as a firewall—even in failure, protecting downstream recipients. In contrast, DeFi lending is almost entirely on-demand; under stress, protocols immediately pass risk back to users, offering no maturity transformation. Why can’t DeFi do this? Because maturity transformation requires credit mechanisms—and DeFi lacks credit systems altogether. Thus, only CeFi can currently fulfill this role.

From the above, it is evident that numerous CeFi institutions have effectively functioned as the banking backbone of the crypto industry.

Therefore, despite the chain-reaction collapses of CeFi institutions during the bear market—which worsened the depth of the downturn and triggered widespread media backlash, with some even calling for “de-CeFi-ification” and advocating that all financial functions should migrate to DeFi, we must adopt a more balanced view. Finance inherently involves risk. For the industry to grow stably, someone must manage risk—and at critical junctures, absorb it. In extreme cases, institutions must act as firewalls, sacrificing themselves to prevent crises from spreading. In the crypto industry, it was CeFi institutions—not DeFi protocols—that took on this risk management role, providing capital and stability to productive sectors. Their contribution to the industry’s evolution cannot be overlooked.

3. The “Three Sins” of CeFi Risk Management

That CeFi institutions effectively served as the banking system in crypto over recent years is undeniable and deserves recognition. But how should we evaluate their performance *as* banks? Frankly, quite poorly. Specifically, while they performed adequately in supplying liquidity to productive sectors, their own risk management was disastrous. Banks are risk managers—if they fail to manage their own risks, let alone protect the broader industry, their performance is fundamentally unacceptable. And indeed, the poor risk governance of CeFi institutions intensified the severity of the recent market crash.

More concretely, some CeFi institutions committed three major errors in risk management:

First, engaging in large-scale, unregulated shadow credit. Many CeFi institutions extended massive unsecured credit lines to each other. In principle, this mirrors traditional interbank lending—an essential mechanism for optimizing capital and risk distribution among financial entities. However, in today’s CeFi landscape, there is no standardized, transparent, or regulated credit market. As a result, these credit arrangements occur opaquely, chaotically, and without rules—neither subject to peer oversight nor public disclosure. We can only treat them as underground transactions, rendering market discipline ineffective. For example, Three Arrows Capital, once managing $18 billion in assets, suffered hundreds of millions in losses from the LUNA crash and subsequently borrowed billions in unsecured credit from over twenty CeFi lenders. These counterparties had no visibility into 3AC’s true financial condition, could not verify fund usage, and were unaware of its parallel borrowings across multiple venues. When 3AC collapsed, it dragged down Voyager, Celsius, and others into insolvency or restructuring. This case starkly illustrates the dangers of non-marketized, shadow banking practices.

Second, mixed operations with arbitrary misuse of funds for high-risk speculation. Many CeFi institutions heavily engage in speculative activities—trading tokens, futures, quant strategies, DeFi arbitrage. Using proprietary capital for such purposes is acceptable if risks are self-contained. However, due to insufficient disclosure and oversight, they often divert client or fundraising proceeds toward speculation, starving productive sectors of needed liquidity. For instance, many crypto venture firms raise funds under the guise of supporting startups, yet deploy capital to speculate on Bitcoin or Ethereum when opportunities arise. Industry insiders know that during speculative frenzies, genuine innovation struggles to raise capital—not because money is scarce, but because it’s diverted into zero-sum games. Speculative capital does not generate lasting value. Such behavior fundamentally violates the principles expected of a banking system.

Third, aggressive leveraging and unchecked expansion of risk exposure. Many CeFi founders come from trading backgrounds, accustomed to high-stakes markets. Their institutions often have deep roots in leveraged trading. During bull markets, bold leveragers stand out, achieving explosive asset growth. In a culture that glorifies asset size and growth speed, winners are often those who take the greatest risks. But this risk appetite is fundamentally misaligned with the conservative ethos required of banking systems. For example, one centralized lending platform long relied on recursive staking to amplify leverage. It nearly collapsed during the March 2020 market crash, survived by implementing hedges, yet continued pursuing self-financed high-leverage growth throughout the bull cycle, achieving remarkable returns. But when the 2022 market crashed from May to June, the same leverage worked in reverse, causing its rapid implosion.

When discussing these failures, it’s tempting to blame individual CeFi leaders’ greed or incompetence—as if the problem stems merely from personal moral failings. Blaming “bad actors” may be convenient, but it’s always shallow and emotionally driven. The leaders of CeFi institutions are no different from anyone else—they will always have moral imperfections, always grapple with greed and fear. The issue isn’t people; it’s systems and infrastructure.

The crypto industry remains in its infancy—immature, lacking a reputation-based credit system, failing to harness blockchain’s potential to enforce transparency and oversight over centralized institutions, and missing foundational infrastructure like fixed-term DeFi lending or inter-institutional repo markets. Credit instruments like bonds are only beginning to emerge. As a result, when the bear market arrived, CeFi institutions collapsed en masse—not containing or isolating risk, but magnifying the crisis.

The crypto industry must first fully acknowledge these structural deficiencies, then establish industry-wide cooperative mechanisms, leveraging tools like SoulBound Tokens (SBTs) to explicitly embed reputation, creditworthiness, and term-based financial products on-chain. It must strive to build inter-institutional lending and repo markets, creating a dedicated money market separate from volatile secondary trading. Only then can the crypto industry transition into a more stable and sustainable growth phase, paving the way for the broad adoption of Web3 and blockchain-powered applications.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News