每个国家都负债累累,那么谁是债主?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

每个国家都负债累累,那么谁是债主?

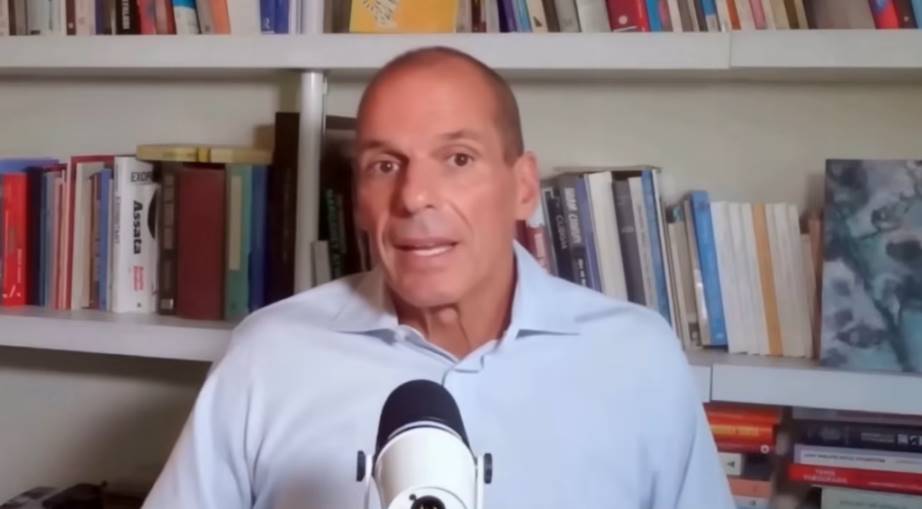

Former Greek finance minister: It's "all of us."

By Yaqi Zhang

Source: Wall Street Insight

Today, every major nation on Earth is deeply mired in debt, raising the century-old question: "If everyone is in debt, who exactly is doing the lending?" Recently, Yanis Varoufakis, former finance minister of Greece, delved into this complex and fragile global debt system on a podcast, warning that it now faces unprecedented risks of collapse.

Yanis Varoufakis explained that lenders to government debt are far from external entities—they form closed-loop systems within nations themselves. Take the United States as an example: the largest creditors to the U.S. government are domestic institutions such as the Federal Reserve and government trust funds like Social Security. The deeper secret lies in the fact that ordinary citizens, through their pensions and savings, hold vast amounts of government bonds, making them collectively the biggest lenders.

For countries like Japan, purchasing U.S. Treasury bonds serves as a tool to recycle trade surpluses and maintain currency stability. Thus, in wealthy nations, government debt has become the safest asset sought after by creditors.

Varoufakis warned that this system could plunge into crisis once confidence collapses—a scenario with historical precedents. While conventional wisdom holds that major economies won’t default, rising global debt levels, high interest rates, political polarization, and climate change are piling up risks that could erode systemic trust and trigger disaster.

Varoufakis summarized the riddle of “who are the creditors?”: the answer is all of us. Through pensions, banks, central banks, and trade surpluses, nations collectively lend to one another, forming a massive, interconnected global debt network. This system has brought prosperity and stability, yet its extreme fragility grows as debt climbs to unprecedented heights.

The issue isn't whether it can last indefinitely—but how the adjustment will come: gradually or suddenly through crisis. He warned that margins for error are shrinking. Although no one can predict the future, structural problems—such as disproportionate benefits going to the rich while poor countries pay exorbitant interest—cannot persist forever, especially since no one truly controls this complex system governed by its own logic.

Highlights from the podcast:

-

In wealthy countries, citizens are both borrowers (benefiting from government spending) and lenders, as their savings, pensions, and insurance policies are invested in government bonds.

-

U.S. government debt is not a burden imposed on unwilling creditors—it’s an asset they actively seek to own.

-

The U.S. is expected to pay $1 trillion in interest during fiscal year 2025.

-

One great irony of modern monetary policy: we create money to save the economy, but these funds disproportionately benefit those already wealthy. The system works—but worsens inequality.

-

Paradoxically, the world needs government debt.

-

Historically, crises erupt when confidence evaporates—when lenders suddenly decide they no longer trust borrowers.

-

If every country has debt, who are the creditors? The answer is all of us. Through our pension funds, banks, insurance policies, and savings accounts; through our central banks; and through currencies generated by trade surpluses and recycled into bond purchases—we collectively lend to ourselves.

-

The real question isn’t whether this system can go on indefinitely—it can’t, just as nothing in history lasts forever. The key question is how it will adjust.

Podcast transcript below:

Heavy Global Debt: The "Mysterious" Lenders Are Ourselves

Yanis Varoufakis:

I want to talk about something that sounds like a riddle—or maybe a magic trick. Every major nation on Earth is deeply buried in debt. The U.S. owes $38 trillion. Japan's debt stands at 230% of its entire economic output. Britain, France, Germany—all running deep deficits. Yet somehow, the world keeps turning, money keeps flowing, markets keep functioning.

This is the puzzle that keeps people awake at night: If everyone is in debt, who is doing the lending? Where is all this money coming from? When you borrow from a bank, the bank has the money—that makes perfect sense. It comes from somewhere: depositors, investors, capital, pools of funds, borrowers. Simple. But scale this up to the national level, and something very strange happens—the math stops making intuitive sense. Let me explain what’s actually happening, because the truth is far more fascinating than most realize. I should warn you: once you understand how this system really works, you’ll never look at money the same way again.

Let’s start with the United States, the easiest case to examine. As of October 2, 2025, U.S. federal debt reached $38 trillion. That’s not a typo—$38 trillion. To put that in perspective, if you spent $1 million every single day, it would take over 100,000 years to spend it all.

Now, who holds this debt? Who are these mysterious lenders? The first answer may surprise you: Americans themselves. The single largest holder of U.S. government debt is actually America’s own central bank—the Federal Reserve. They hold around $6.7 trillion in U.S. Treasuries. Think about that for a moment: the U.S. government owes money to its own government bank. But that’s only the beginning.

Another $7 trillion exists in what we call “intragovernmental holdings”—money the government owes itself. The Social Security Trust Fund holds $2.8 trillion in U.S. debt. Military retirement funds hold $1.6 trillion. Medicare takes up a large chunk too. So the government borrows from Social Security to fund other programs, promising to repay later. It’s like taking money from your left pocket to pay your right pocket. So far, the U.S. effectively owes itself about $13 trillion—more than a third of total debt.

The question “Who are the lenders?” starts to get weird, doesn’t it? But let’s continue. The next major category is private domestic investors—ordinary Americans participating through various channels. Mutual funds hold about $3.7 trillion. State and local governments hold $1.7 trillion. Then there are banks, insurers, pension funds, and others. In total, private American investors hold roughly $24 trillion in U.S. government debt.

And here’s where it gets truly interesting. These pension and mutual funds are funded by American workers, retirement accounts, and everyday savers. So, in a very real sense, the U.S. government is borrowing directly from its own citizens.

Let me tell you a story about how this works in practice. Imagine a schoolteacher in California, 55 years old, who’s taught for 30 years. Every month, part of her salary goes into her pension fund. That fund needs to invest the money somewhere safe—somewhere reliable to generate returns so she can retire comfortably. What’s safer than lending to the U.S. government? So her pension fund buys Treasury bonds. That teacher might also worry about national debt. She watches the news, sees those scary numbers, and feels anxious—and rightly so. But here’s the twist: she’s one of the lenders. Her retirement depends on the government continuing to borrow and pay interest on those bonds. If the U.S. paid off all its debt tomorrow, her pension fund would lose one of its safest, most reliable investments.

This is the first big secret of government debt: in wealthy countries, citizens are both borrowers (benefiting from government spending) and lenders, because their savings, pensions, and insurance policies are invested in government bonds.

Now let’s move to the next category: foreign investors. This is what most people picture when they think about who holds U.S. debt. Japan holds $1.13 trillion. The UK holds $723 billion. Foreign investors—governments and private entities combined—hold about $8.5 trillion in U.S. Treasuries, roughly 30% of publicly held debt.

But what’s fascinating about foreign holdings is: why do other countries buy U.S. debt? Let’s take Japan. Japan is the world’s third-largest economy. They export cars, electronics, and machinery to the U.S. Americans pay in dollars, so Japanese companies earn huge sums in USD. Now what? These companies need to convert dollars into yen to pay employees and suppliers at home. But if they all try to sell dollars at once, the yen would surge, making Japanese exports more expensive and less competitive.

So what does Japan do? The Bank of Japan buys those dollars and invests them in U.S. Treasury bonds. It’s a way to recycle trade surpluses. Think of it like this: the U.S. imports physical goods—Sony TVs, Toyota cars—while Japan uses those dollars to buy financial assets from the U.S., namely Treasury bonds. Money flows in a loop, and debt is just the accounting record of that loop.

This leads to a crucial point for much of the world: U.S. government debt is not a burden forced upon reluctant creditors—it’s an asset they actively want. U.S. Treasuries are considered the safest financial asset in the world. When uncertainty hits—war, pandemics, financial crises—money floods into U.S. debt. This is known as a “flight to safety.”

But I’ve focused on the U.S. What about the rest of the world? Because this is a global phenomenon. Global public debt now stands at $111 trillion—95% of global GDP. In just one year, debt grew by $8 trillion. Japan may be the most extreme case. Japanese government debt is 230% of GDP. If you imagine Japan as a person earning £50,000 a year but owing £115,000, that would be bankruptcy territory. And yet, Japan keeps functioning. Japanese government bond yields hover near zero—or even negative. Why? Because nearly all Japanese debt is held domestically. Japanese banks, pension funds, insurers, and households hold 90% of Japanese government debt.

There’s a psychological element here. The Japanese are known for high savings rates—they save diligently. Those savings are invested in government bonds because they’re seen as the safest store of wealth. The government then uses that borrowed money for schools, hospitals, infrastructure, and pensions—benefiting the very citizens whose savings funded it. It’s a closed loop.

How It Works and Inequality: QE, Trillion-Dollar Interest, and the Global Debt Trap

Now let’s discuss how it actually functions: Quantitative Easing (QE).

Quantitative easing means central banks digitally create money out of thin air—by typing numbers into computers—and use that newly created money to buy government bonds. The Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan—they don’t need to raise funds elsewhere to lend to their governments. They simply increase the digits in an account. Money that didn’t exist before—now it does. During the 2008–2009 financial crisis, the Fed created about $3.5 trillion this way. During the pandemic, they created another massive sum.

Before you think this is some elaborate scam, let me explain why central banks do this and how it’s supposed to work. During crises like financial meltdowns or pandemics, economies stall. People stop spending out of fear. Businesses stop investing due to lack of demand. Banks stop lending due to default fears. A vicious cycle forms: less spending means less income, which means even less spending. At that point, governments must step in—build hospitals, send stimulus checks, rescue failing banks—whatever it takes. But governments need to borrow heavily for this. In normal times, enough people might lend at reasonable rates. But in emergencies, there may not be enough willing lenders. So central banks step in—create money and buy government bonds—to keep interest rates low and ensure governments can borrow what they need.

Theoretically, this new money flows into the economy, encourages lending and spending, and helps end recessions. Once the economy recovers, central banks reverse the process—sell the bonds back into the market, pull the money out, and restore normalcy.

But reality is messier. The first round of QE after the financial crisis seemed effective—it prevented total systemic collapse. But at the same time, asset prices soared—stocks and real estate. Why? Because all that new money ended up in the hands of banks and financial institutions. They didn’t necessarily lend it to small businesses or homebuyers. Instead, they used it to buy stocks, bonds, and property. So the wealthy—who already owned most financial assets—got richer.

Research by the Bank of England estimated that QE boosted stock and bond prices by about 20%. Behind that figure: the wealthiest 5% of UK households saw average wealth rise by £128,000, while families with little or no financial assets gained almost nothing. This is one of the great ironies of modern monetary policy: we create money to save the economy, but it disproportionately enriches those already rich. The system works—but it widens inequality.

Now, let’s talk about the cost of all this debt—because it’s not free. Interest accumulates. The U.S. is projected to pay $1 trillion in interest during fiscal year 2025. Yes—just interest payments, $1 trillion. That’s more than the entire military budget. It’s the second-largest item in the federal budget after Social Security, and it’s rising fast. Interest payments have nearly tripled in three years—from $497 billion in 2022 to $909 billion in 2024. By 2035, interest payments are expected to hit $1.8 trillion annually. Over the next decade, the U.S. government will spend $13.8 trillion just on interest—money not going to schools, roads, healthcare, or defense. Just interest.

Think about what that means: every dollar spent on interest is a dollar not spent elsewhere. It’s not building infrastructure, funding research, or helping the poor. It’s just paying bondholders. Here’s the current math: as debt rises, interest payments rise; as interest payments rise, deficits grow; as deficits grow, more borrowing is needed. It’s a feedback loop. The Congressional Budget Office projects that by 2034, interest costs will consume about 4% of U.S. GDP and 22% of federal revenue—meaning more than one out of every five tax dollars will go purely to interest.

But the U.S. isn’t alone. Across the OECD—a club of wealthy nations—interest payments now average 3.3% of GDP, more than these governments spend on defense combined. Globally, over 3.4 billion people live in countries where government debt interest exceeds spending on education or healthcare. Some governments pay more to bondholders than they do educating children or treating patients.

For developing countries, the situation is worse. Poor nations paid a record $96 billion servicing foreign debt. In 2023, their interest costs hit $34.6 billion—four times higher than a decade ago. In some countries, interest payments alone consume 38% of export earnings. That money could have modernized armies, built infrastructure, educated populations—but instead, it flows as interest to foreign creditors. Sixty-one developing countries now spend 10% or more of government revenue on interest. Many are trapped—spending more to repay old loans than they receive in new ones. It’s like drowning—paying your mortgage while watching your house sink underwater.

So why don’t countries just default—refuse to pay? Default does happen. Argentina has defaulted nine times in history. Russia defaulted in 1998. Greece nearly collapsed in 2010. But the consequences are catastrophic: shut out from global credit markets, currency collapse, unaffordable imports, retirees losing life savings. No government defaults unless it has no choice.

For major economies like the U.S., UK, Japan, and core European nations, default is unthinkable. These countries borrow in their own currencies—they can always print more money to repay. The problem isn’t solvency—it’s inflation. Printing too much devalues the currency, which is itself another kind of disaster.

The Four Pillars Holding Up the Global Debt System—and Its Risks of Collapse

This raises the question: what keeps this system running?

First is demographics and savings. Populations in wealthy nations are aging. People live longer and need safe places to store retirement wealth. Government bonds fulfill that need. As long as people demand safe assets, there will be demand for government debt.

Second is the structure of the global economy. We live in a world of massive trade imbalances. Some nations run large trade surpluses—exporting far more than they import—while others run huge deficits. Surplus nations often accumulate financial claims—via government bonds—on deficit nations. As long as these imbalances persist, debt will persist.

Third is monetary policy itself. Central banks use government bonds as policy tools—buying them to inject money into the economy, selling them to withdraw it. Government debt acts as lubricant for monetary policy. Central banks need abundant government bonds to function.

Fourth, in modern economies, safe assets are valuable precisely because they’re scarce. In a risky world, safety commands a premium. Government bonds from stable nations provide that safety. If governments actually repaid all their debt, there’d be a shortage of safe assets. Pension funds, insurers, banks all struggle to find secure investments. Paradoxically, the world needs government debt.

But here’s what keeps me awake—and should concern us all: this system remains stable until it isn’t. Throughout history, crises erupt when confidence vanishes—when lenders suddenly decide they no longer trust borrowers. That happened in Greece in 2010. In the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. In many Latin American nations in the 1980s. The pattern is always the same: years of apparent normality, then suddenly triggered by an event or loss of faith—investors panic, demand higher interest rates, governments can’t pay, crisis hits.

Could this happen to a major economy? Could it happen to the U.S. or Japan? Conventional thinking says no—because these nations control their own currencies, have deep financial markets, and are “too big to fail” globally. But conventional wisdom has been wrong before. In 2007, experts said nationwide housing prices couldn’t fall—then they did. In 2010, experts called the euro indestructible—then it nearly collapsed. In 2019, no one predicted a global pandemic would paralyze the world economy for two years.

Risks are accumulating. Global debt is at peacetime highs never seen before. After years of near-zero rates, interest rates have risen sharply—making debt servicing far more expensive. Political polarization in many nations makes coherent fiscal policy harder to achieve. Climate change demands massive investment—funds that must be raised atop already record-high debt. Aging populations mean fewer workers supporting retirees, straining government budgets.

Finally, there’s trust. The entire system relies on confidence: that governments will honor payments, that currencies will hold value, that inflation will remain under control. If that trust collapses, the whole system unravels.

Who Are the Creditors? All of Us

Back to our original question: every country has debt—so who are the creditors? The answer is all of us. Through our pension funds, banks, insurance policies, and savings accounts; through our central banks; through currencies created by trade surpluses and recycled into bond purchases—we collectively lend to ourselves. Debt is a claim by one part of the global economy on another—a vast, interconnected web of obligations.

This system has delivered immense prosperity—funding infrastructure, research, education, healthcare. It allows governments to act during crises without being limited by tax revenues. It creates financial assets that support retirement and provide stability. But it’s also extremely fragile—especially as debt reaches unprecedented levels. We’re in uncharted territory. Never before in peacetime have governments borrowed so much, nor have interest payments consumed such a large share of budgets.

The question isn’t whether this system can last forever—it can’t. Nothing in history lasts forever. The real question is how it will adjust. Will it be gradual? Will governments slowly rein in deficits while growth outpaces debt accumulation? Or will it come suddenly—as a crisis forcing all painful changes at once?

I don’t have a crystal ball. No one does. But I can tell you this: the longer we wait, the narrower the path between these outcomes becomes. Margins for error are shrinking. We’ve built a global debt system where everyone owes everyone else, central banks create money to buy government bonds, and today’s spending is paid for by tomorrow’s taxpayers. In such a world, the rich gain disproportionate benefits from policies meant to help everyone, while poor countries pay heavy interest to wealthy creditors. This cannot go on forever. We will have to make choices. The only questions are what, when, and whether we manage the transition wisely—or let it spiral out of control.

When everyone is drowning in debt, the riddle of “who is lending?” isn’t really a riddle at all—it’s a mirror. When we ask who the lenders are, we’re really asking: who’s involved? Where is this system headed? Where is it taking us? And the unsettling truth is: no one truly is in control. The system has its own logic and momentum. We’ve built something complex, powerful, and fragile—and we’re all struggling to steer it.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News