From "Burning Money" to Industrial Ecosystem: Web3 Is Retracing the Internet's Old Path

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

From "Burning Money" to Industrial Ecosystem: Web3 Is Retracing the Internet's Old Path

From storytelling and token issuance, to acquiring users through subsidies, then validating real-world use cases, and ultimately moving toward ecosystem structuring.

By: Jiayi

Some say crypto is a Ponzi, a bubble, a speculative game destined to go to zero.

Others say Web3 is a revolution, a paradigm shift, a new stage of civilization built upon technological continuity.

Two voices, one fractured narrative.

Don't rush to pick sides—first, consider a simpler conclusion:

The fundamental logic of business has never changed.

Whether it's Web2, evolving from portals to apps, or Web3, shifting from token issuance and storytelling to infrastructure building, beneath the surface both follow the same old path—only this time, narratives wrap around protocols, and capital hides within code.

Looking back over the past decade, China’s internet trajectory is clear: concept-driven, funding ahead of user growth; subsidies pulling traffic, capital fueling expansion; followed by layoffs, efficiency drives, and profitability pushes; then platform transformation and technical restructuring. Today’s Web3 is walking a strikingly similar developmental rhythm.

Over the past year, competition among projects has evolved into a battleground where TGEs and Airdrops serve as user acquisition tools. No one wants to fall behind, yet no one knows how much longer this "user exchange" race will last. So I’ve written this piece to break down what seems like chaotic narratives into several more traceable stages.

Let’s follow history’s footprints to see how Web3 arrived at today—and where it might be headed.

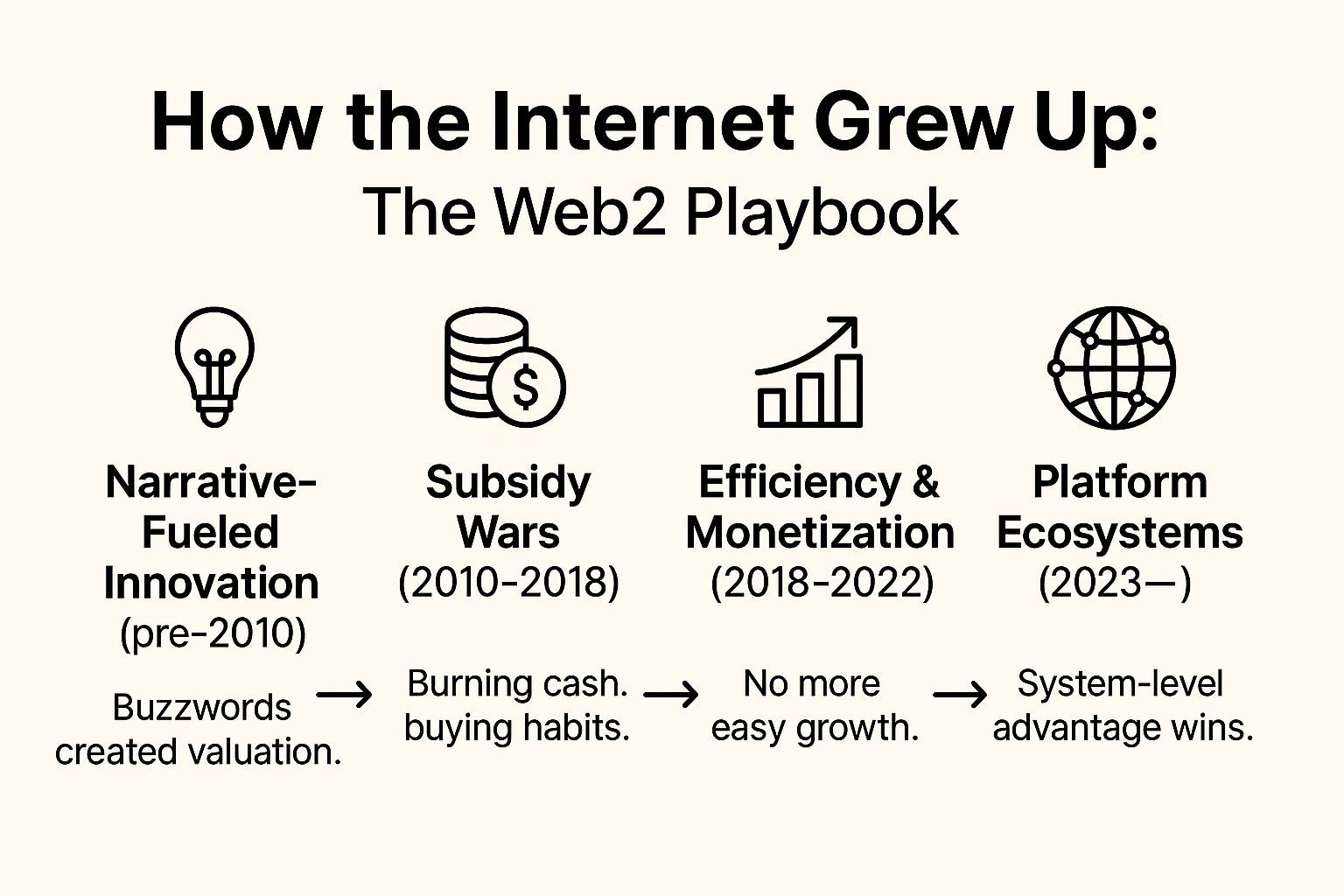

1. Review of Internet Industry Development Stages: From Cash-Burning Expansion to Industrial Collaboration

Most people are likely familiar with this history:

The early internet was a massive carnival, where over a dozen apps competed to let you “freeload”—a single phone number could feed you, hail rides, cut your hair, and give you massages, like being in perpetual holiday mode.

Today’s internet, however, is a system that’s already completed most of its journey: you know which platform offers the cheapest deals, which app to open for maximum efficiency in specific scenarios, and the ecosystem landscape is largely settled, with innovation now embedded in operational efficiency.

So without over-explaining, here’s a brief breakdown of four stages—reviewing these logics may help us better understand the path Web3 is now replicating.

1. Narrative-Driven, Mass Innovation Phase (Pre-2010)

This was an era defined by “buzzwords.”

“Internet+” became a magic key—no matter if you were in healthcare, education, transportation, or local services, just attach those three characters and you could unlock hot money and attention. Entrepreneurs weren’t rushing to build products but first scrambling to identify trends, create concepts, and write business plans. Investors weren’t chasing revenue curves but asking whether a founder could tell a “new enough, big enough, and easy-to-imagine” story.

O2O, social e-commerce, sharing economy—the rotating buzzwords drove valuations skyward, with fundraising rhythms dictated by narrative momentum. Core assets weren’t users, products, or data, but a well-crafted pitch deck that aligned perfectly with the trend.

This was an era of “first mover advantage.” Validating product-market fit or business model came second; you had to get your story onto the风口 first to even qualify for the game.

2. Cash-Burning Expansion, Traffic Competition Phase (2010–2018)

If the previous phase was about capturing attention through stories, this one was about seizing markets through subsidies.

From the Didi-Kuaidi ride-hailing war to the Mobike-ofo bike-sharing chaos, the entire industry converged on one strategy: use capital to gain scale, price cuts to shape habits, and losses to secure access points. Whoever raised another round could keep expanding; whoever secured the next investment would survive on the battlefield.

This was a period where user acquisition trumped everything else. Experience, efficiency, and product moats took a back seat—the key was becoming users’ default choice.

Subsidy wars intensified, low prices became standard: rides under $1, bike rentals for a penny, offline stores plastered with app QR codes offering free meals, haircuts, and massages. It looked like service democratization, but was actually a capital-controlled traffic grab.

It wasn’t about who had a better product, but who could burn more cash; not about solving problems, but about who could “claim territory” faster.

In the long run, this also laid the groundwork for later refinement—when users are bought, you must work harder to retain them; when growth relies on external forces, self-sustainability becomes impossible.

3. Grounding and Refined Operations Phase (2018–2022)

Eventually, after too many stories, the industry faced a hard truth: “After growth, how do you ground?”

Starting in 2018, mobile internet user growth slowed, traffic红利 gradually faded, and customer acquisition costs kept rising.

According to QuestMobile, by the end of September 2022, monthly active users on China’s mobile internet neared 1.2 billion—up only about 100 million since 2018, a near four-and-a-half-year crawl showing sharply decelerated growth. Meanwhile, online shopping users reached 850 million in 2022, nearly 80% of all internet users, signaling saturation.

At the same time, many funding-dependent “story-first” projects began collapsing. O2O and the sharing economy saw the most intense cleanups: Street Power, Bluegogo, Wukong Travel—all fell, exposing unsustainable growth models lacking user loyalty.

Yet precisely during this downturn, truly viable projects emerged. They shared one trait: their traction wasn’t driven by subsidies, but by fulfilling real needs and systemic capabilities that closed their business loops.

Meituan, for example, built a full-service chain in local life—from order placement to fulfillment, traffic to supply—evolving into a platform-level infrastructure. Pinduoduo rapidly captured lower-tier e-commerce with extreme supply chain integration and operational efficiency. Social media remained dominated by Tencent, e-commerce by Alibaba, gaming split between Tencent and NetEase.

What they shared wasn’t “vision,” but stability and clarity in execution—structurally closing the loop from traffic to value, becoming sustainable product systems.

Growth was no longer the sole goal. The real dividing line became whether growth could translate into structural retention and value accumulation. Extensive expansion was weeded out; only system-level projects capable of creating positive feedback across efficiency, product, and operations survived.

This marked the end of the narrative-driven era—business models now needed “self-closing” capabilities: retaining users, sustaining the model, and maintaining structural integrity.

4. Ecosystem Maturation, Technological Breakthroughs for New Opportunities (2023–Present)

Once dominant players emerged, survival ceased to be an issue for most, and true divergence began.

Competition between platforms shifted from user battles to ecosystem capability contests. As leading platforms closed off growth paths, the industry entered a stable, resource-concentrated phase led by coordination ability. True moats were no longer about feature superiority, but whether internal systems operated efficiently, stably, and cohesively.

This became the era of system builders. With格局 largely fixed, any new entrant seeking breakthroughs must exploit structural gaps or technological discontinuities.

In this phase, almost all high-frequency, essential sectors have been claimed by giants. In the past, being first and burning fast secured position; today, growth must be embedded within systemic capability. Platform logic evolved: from stacking multiple products to building ecosystem flywheels, from individual user acquisition to organizational-level synergy.

Tencent integrated WeChat, mini-programs, and advertising into a seamless internal flow; Alibaba restructured Taotian, Cainiao, and DingTalk to reconnect commercial chains and regain efficiency leverage. Growth no longer came from new users, but from structural compounding generated by system self-operation.

As user pathways, traffic entrances, and supply chain nodes became controlled by a few top platforms, industrial structures grew increasingly closed, leaving little room for newcomers.

Yet within this tightening structure, ByteDance emerged as an anomaly.

Instead of fighting for resources inside existing ecosystems, it took a detour—starting from foundational technology, using recommendation algorithms to rebuild content distribution logic. While mainstream platforms still relied on social graphs for traffic routing, ByteDance created a user-behavior-based distribution system, establishing its own user base and commercial loop.

This wasn’t incremental improvement—it was a technological leap that bypassed existing paths and rebuilt growth structures.

ByteDance reminds us: even in a rigid industrial landscape, new players can emerge if structural fractures or technological voids remain. But this time, the path is narrower, the pace faster, and the bar higher.

Today’s Web3 sits precisely in such a critical zone.

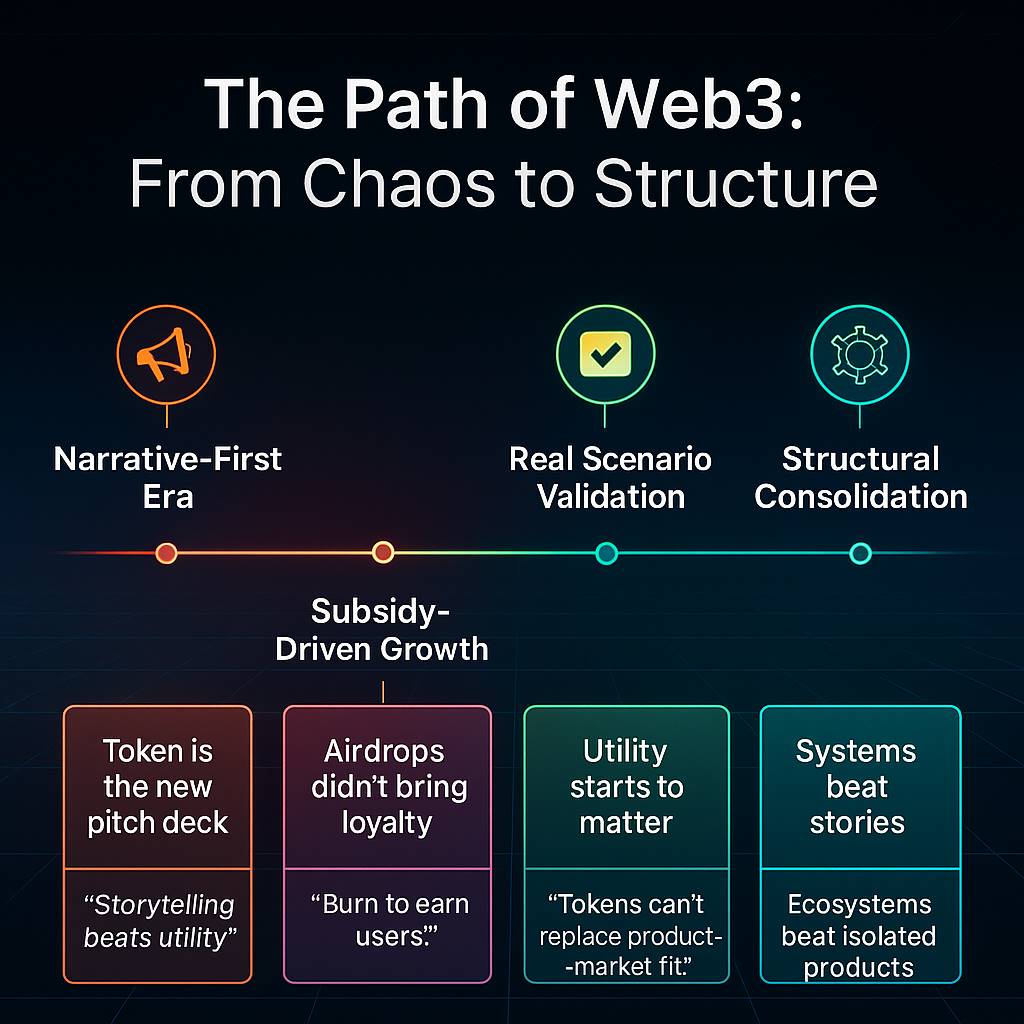

2. Current Stage of Web3: A Parallel Mirror of Internet Evolution Logic

If Web2’s rise was an industrial reorganization powered by mobile internet and platform models, then Web3’s starting point is a system reconstruction built on decentralized finance, smart contracts, and on-chain infrastructure.

The difference? Web2 established strong connections between platforms and users; Web3 attempts to shatter and redistribute “ownership,” rebuilding new organizational structures and incentive mechanisms on-chain.

But the underlying drivers haven’t changed: from story-pulling to capital-driving, from user grabs to ecosystem flywheels, Web3’s path mirrors Web2 almost exactly.

This isn’t mere comparison—it’s a parallel replication of structural trajectories.

Only this time, the fuel is token incentives; the architecture is modular protocols; the competition revolves around TVL, active addresses, and airdrop point tables.

We can roughly divide Web3’s development so far into four phases:

1. Concept-Driven Phase—Token Launch: Story First, Capital Follows

If Web2’s early days thrived on the “Internet+” narrative template, then Web3’s opening act was written in Ethereum’s smart contracts.

In 2015, Ethereum launched, and the ERC-20 standard provided a unified interface for asset issuance, making “token creation” a basic function accessible to every developer. It didn’t alter the essence of fundraising but dramatically lowered the technical barriers to issuance, circulation, and incentives, turning “technical narrative + contract deployment + token incentive” into the standard startup model for early Web3 ventures.

This phase’s explosion stemmed primarily from technological advances—blockchain empowered entrepreneurs in standardized form, transforming asset issuance from permissioned to open-source.

No need for a complete product, no mature user base required—just a whitepaper clearly articulating a blockchain-powered blockchain 1.0 vision, an enticing token model, and a working smart contract, and a project could instantly close the loop from “idea” to “fundraising.”

Early Web3 innovation wasn’t due to smarter teams, but because blockchain adoption unleashed imagination during the blockchain 1.0 era.

Capital quickly formed a “betting mechanism”: whoever seized a new sector first, launched earliest, and pushed the narrative hardest stood to gain exponential returns.

This birthed an “unprecedented capital efficiency”: between 2017 and 2018, the ICO market exploded, becoming one of the most controversial yet iconic fundraising phases in blockchain history.

According to CoinDesk, in Q1 2018 alone, ICO fundraising hit $6.3 billion—118% of the total for all of 2017. Telegram’s ICO raised $1.7 billion; EOS raised $4.1 billion over a year, setting a record.

During the “everything can be blockchain” window, simply adding a label and crafting a narrative—even without a clear roadmap—allowed projects to pre-cash future valuations. DeFi, NFT, Layer1, GameFi… each buzzword opened a window. Project valuations soared to hundreds of millions or even billions before tokens ever traded.

This offered low-barrier access to capital markets and gradually established a clear exit path: secure early positioning in the primary market, trigger sentiment via narrative and liquidity in the secondary market, then exit during the window.

Under this mechanism, valuation wasn’t based on progress made, but on who moved first, who best manipulated sentiment, and who controlled liquidity release timing.

At its core, this reflects a classic trait of blockchain’s early paradigm—infrastructure newly deployed, cognitive space unoccupied, prices forming before products exist.

Thus arose Web3’s “concept dividend era”: value defined by narrative, exits driven by emotion. Projects and capital search for certainty within a liquidity-driven structure.

2. Cash-Burning Expansion Phase—Project Clustering, Full-Scale User Wars

All change began with one “the most expensive thank-you letter in history.”

In 2020, Uniswap airdropped 400 UNI tokens to early users—each worth about $1,200 at the time. The team called it “community appreciation,” but the industry recognized it as something else: the optimal cold-start solution.

What started as a gesture of goodwill accidentally opened Pandora’s box: projects realized tokens could buy loyalty, traffic, even the illusion of a community.

Airdrops went from optional to mandatory.

Since then, the lightbulb moment arrived—virtually every new project treats “airdrop anticipation” as a default cold-start module. To showcase ecosystem vitality, they pay users with tokens, making point systems, interaction tasks, and snapshots a standard toolkit.

Many projects fell into a “incentive-driven rather than value-driven” growth illusion.

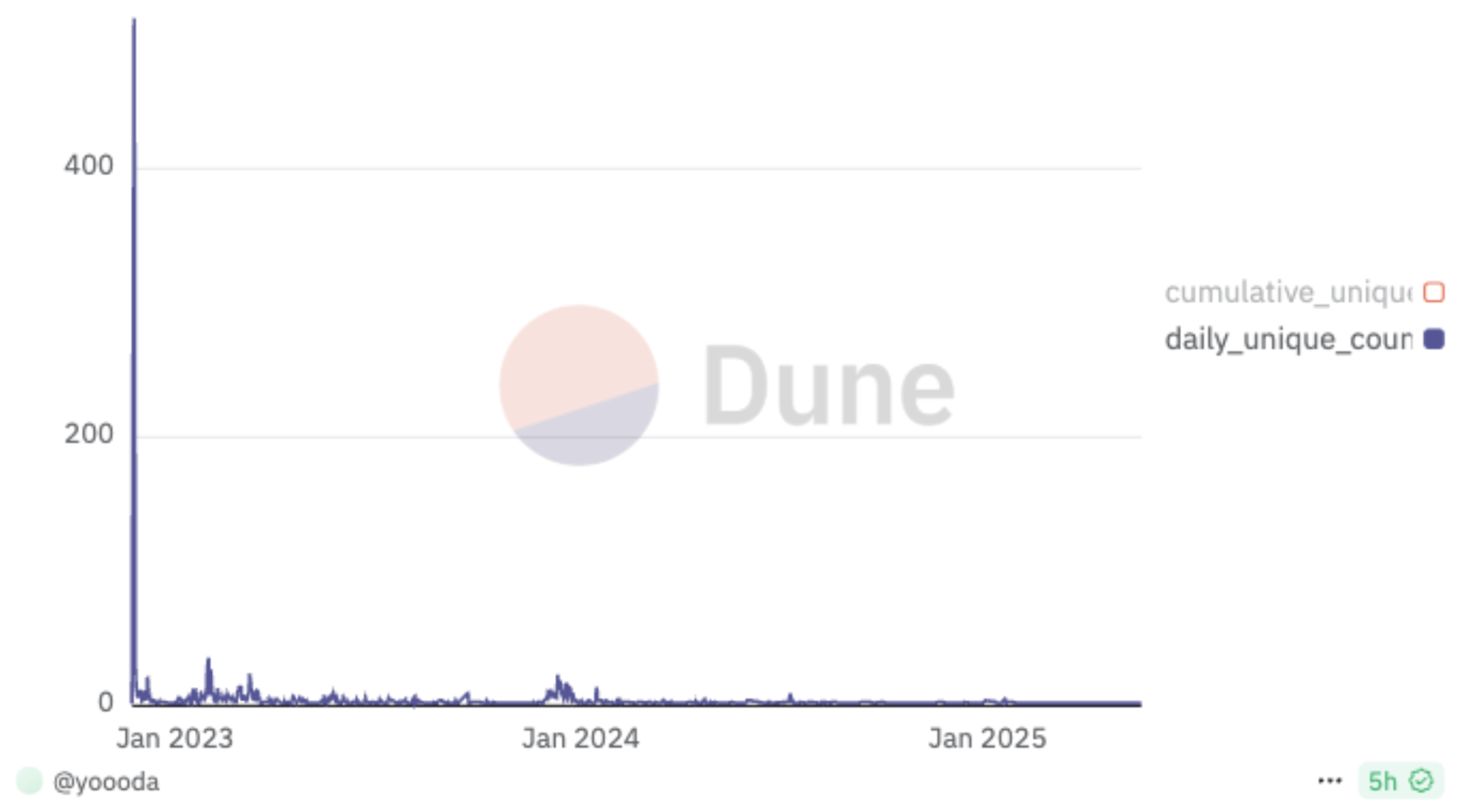

On-chain metrics skyrocketed, founders basked in “success” fantasies: millions of users pre-TGE, hundreds of thousands of daily active users—then post-TGE, activity crashed overnight.

I recall in 2024, Fusionist’s on-chain DAU briefly exceeded 40,000, but immediately after Binance announced its listing, on-chain activity plummeted to near zero.

I’m not dismissing airdrops. At heart, they’re a way to purchase user behavior—an effective user acquisition tool during cold starts that doesn’t drain funding. But their marginal returns are rapidly diminishing. Many projects are stuck in formulaic airdrop cycles. The real question is whether your business scenario and product strength can retain users post-acquisition. That’s the true return to value and the only viable path for survival. (Note: projects surviving solely on secondary market manipulation are outside this discussion.)

Ultimately, bribing users isn’t the core of growth. Without anchoring to actual use cases, airdrops ultimately erode either the project’s or users’ interests. When the business model lacks closure, the token becomes the sole reason users act. Once TGE completes and rewards stop, users naturally walk away.

3. Commercial Validation Phase—Real Use Cases, Narrative Testing

I often ask project teams one thing before they start distributing tokens:

Exactly which problem are you solving, and for whom? Who are the key contributors? After TGE, does this use case still stand? Will anyone genuinely stay and use it?

Many respond that token incentives can rapidly grow their user base. My immediate follow-up: “Then what?”

Usually, they pause, smile awkwardly: “Well…”

And then—nothing.

If you’re only aiming to buy interactions with “rewards,” you might as well just launch a Meme. At least everyone knows it’s an emotional play, with no expectation of retention.

Finally, people are looking back: Where did all this traffic, interaction, and distributed tokens lead? In the end, I realize I was the clown🤡.

So the keywords now are: use cases, user needs, product architecture. Only through genuine scenarios and solid structures can a project forge its own sustainable growth path.

To be honest, I don’t particularly like Kaito’s business logic—it feels like the ultimate form of “bribery culture,” heavily exploiting incentive mechanisms, arguably repackaging the relationship between platforms and content.

Yet undeniably, Kaito succeeded. It represents a real business scenario where pre-TGE anticipation accelerated market capture, and post-TGE, the party continues. Because Kaito provides a clear logic: KOLs promote projects, the pig pays while the sheep gets shorn, and crucially, key players remain on the Kaito platform itself.

Though many KOLs may recognize this system will eventually backfire, in a structurally opportunistic market, “strategic compliance” becomes the most rational choice.

I’m also encouraged to see more projects building around authentic use cases—whether trading, DeFi, or foundational identity systems.

Teams that picked the right direction at the right time and built real products are now taking root through positive feedback loops in vertical niches—from usage to retention, from retention to monetization—gradually carving out industrial paths.

The clearest examples are exchange-type products: they turn high-frequency demand into structural traffic, then close the loop via assets, wallets, and ecosystem integrations, tracing Web3’s “structural evolution path.”

4. Structural Consolidation Phase—Platform Maturation, Shrinking Variables

Genuine, self-reinforcing business scenarios are the entry ticket to industrial influence.

Binance, for instance, started with trading and gradually connected liquidity, asset issuance, on-chain expansion, and traffic gateways, forming an end-to-end coordination system from off-chain to on-chain. Solana leveraged lightweight infrastructure and superior base-layer performance to cultivate a feedback loop of community, developers, and tooling.

This marks a shift from project experimentation to structural consolidation—not racing for speed, but competing on systemic completeness.

But this doesn’t mean new projects have no breakout chance. The ones that truly succeed won’t be the loudest or best-marketed, but those that “fill gaps” structurally or “rebuild models” fundamentally.

Remember ByteDance in the mobile internet era?

I believe in the post-blockchain era, a new cycle driven by AI is emerging. There will surely be a project like ByteDance that, leveraging AI at the right inflection point, rapidly builds a robust structure, achieving industrial breakthrough and self-closure.

Web2’s platform era left us giants and flywheels—and also gap-exploiters like ByteDance. Likewise, Web3’s structural phase may nurture the next variable project that “breaks out from the edge” through superior architecture.

Just imagine: if it’s infrastructure, it should be foundational tech built for the native AI era, driving technological product development—just as Ethereum did in the blockchain 1.0 era;

If it’s a dApp, it must leverage AI to dismantle existing user barriers (Web3’s usability is too high) and disrupt current business orders.

If someone asks me how Web3’s future will unfold?

I’d say: “Just as everything could be internet-enabled, its true potential lies in the post-blockchain era—reconstructing usage pathways, lowering collaboration barriers, and giving rise to a new wave of viable products and systems.”

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News