After venture capital drops 70%, the crypto industry enters merger and acquisition season: buy existing or build from scratch?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

After venture capital drops 70%, the crypto industry enters merger and acquisition season: buy existing or build from scratch?

This is an era of strategic exits.

By: Saurabh Deshpande

Translated by: Luffy, Foresight News

Coinbase acquired Deribit for $2.9 billion, marking the largest M&A deal in cryptocurrency history.

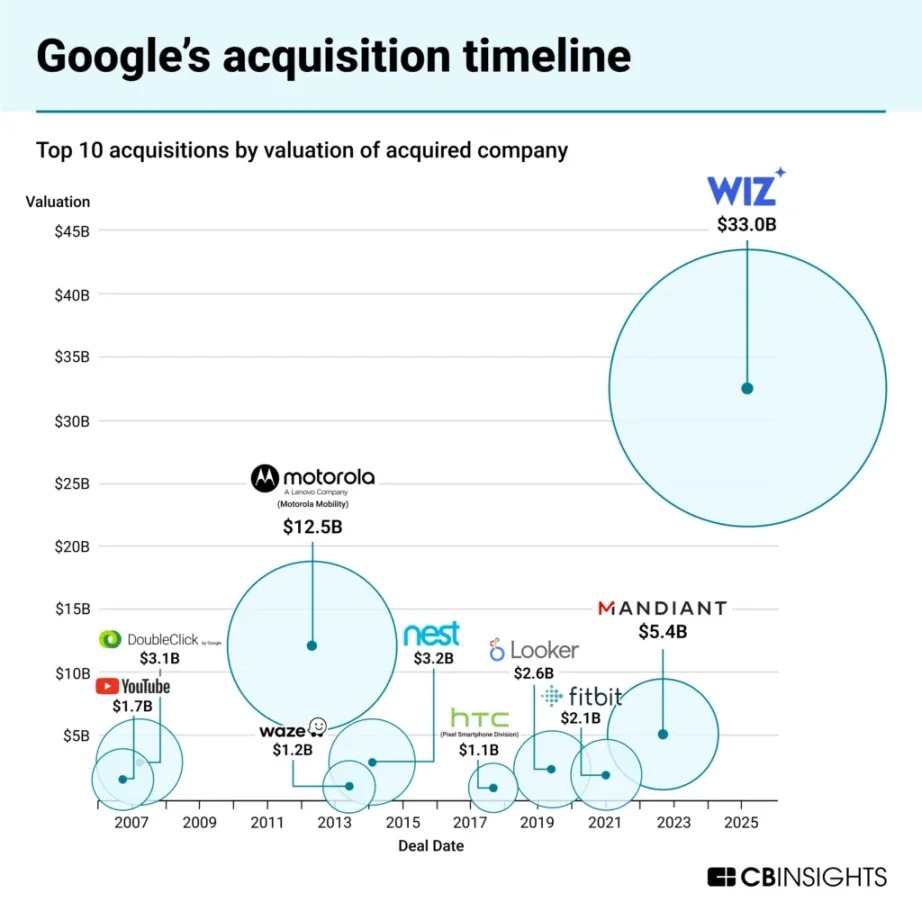

History in the tech sector follows a similar pattern. Google has acquired 261 companies to date. These acquisitions gave rise to products such as Google Maps, Google AdSense, and Google Analytics. Among them, perhaps the most significant was Google’s $1.65 billion acquisition of YouTube in 2004. In Q1 2025, YouTube generated $8.9 billion in revenue, accounting for 10% of Alphabet’s (Google's parent company) total revenue. Similarly, Meta has completed 101 acquisitions so far. Instagram, WhatsApp, and Oculus are prominent examples. Instagram generated over $65 billion in annual revenue in 2024, contributing more than 40% of Meta’s total business revenue.

Buy built, or build yourself?

The cryptocurrency industry is no longer new. The number of crypto users is estimated at 659 million, with Coinbase having over 105 million users, while global internet users stand at approximately 5.5 billion. Therefore, crypto users now represent 10% of all internet users. These numbers matter because they help us identify the sources of future growth.

User growth is an obvious path forward. Currently, we've only developed use cases for crypto in finance. If other applications adopt blockchain technology as infrastructure, the total market size would expand dramatically. Acquiring existing users, cross-selling, and increasing per-user revenue are some ways established companies can grow.

When the pendulum swings toward acquisition

Acquisitions solve three critical problems that simple fundraising cannot. First, in highly specialized fields where experienced developers are scarce, acquisitions facilitate talent acquisition. Second, in environments where organic growth is increasingly expensive, acquisitions enable user acquisition. Third, acquisitions accelerate technological integration, allowing protocols to go beyond their original use cases. These issues will be further explored later with industry examples.

We are in the midst of a new wave of M&A in crypto. Coinbase acquired Deribit for a record $2.9 billion; Kraken acquired the CFTC-regulated retail futures trading platform NinjaTrader for $1.5 billion; Ripple acquired multi-asset prime broker Hidden Road for $1.25 billion and previously made an offer to acquire Circle, which was rejected.

These deals reflect shifting priorities in the space. Ripple seeks distribution and regulatory channels, Coinbase pursues options trading volume, and Kraken fills product gaps. All these acquisitions stem from strategic positioning, survival, and competitive dynamics.

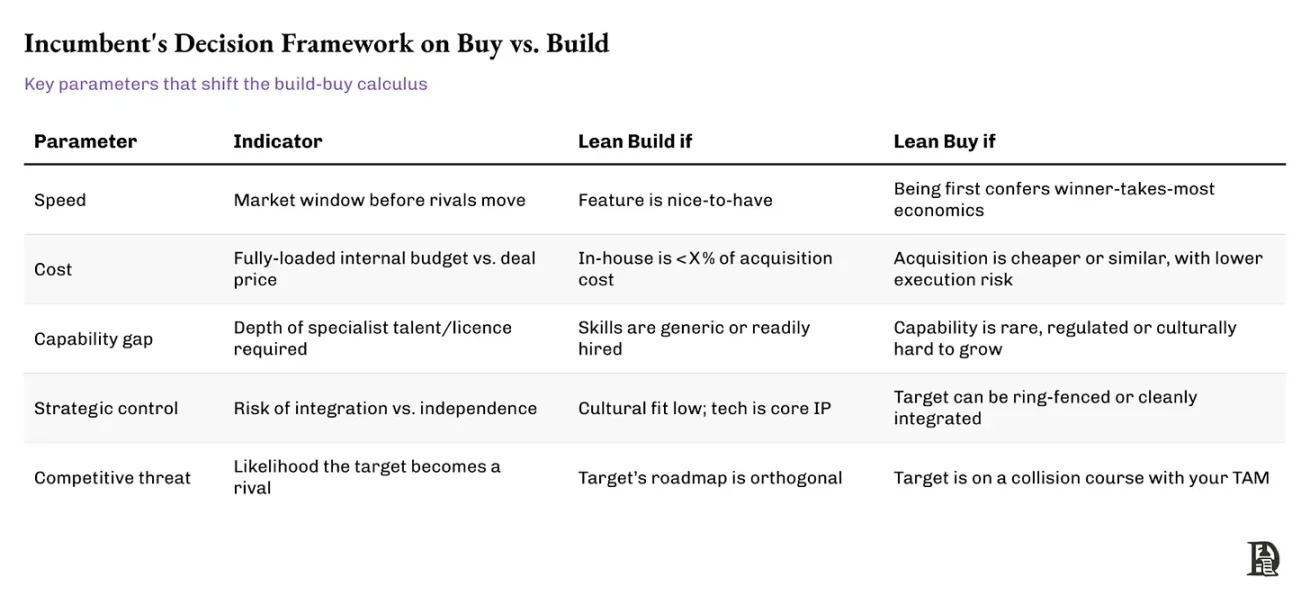

The table below illustrates how incumbent players think when weighing build vs. buy decisions.

While the table summarizes key trade-offs in build-vs-buy decisions, incumbents often act decisively based on unique signals. A strong example is Stripe’s 2020 acquisition of Nigeria’s Paystack. Building infrastructure in Africa would have required navigating steep learning curves around regulation, local integration, and merchant onboarding.

Stripe chose acquisition. Paystack had already solved local compliance, built a merchant base, and proven its distribution capability. Stripe’s acquisition met multiple criteria: speed (first-mover advantage in a growing market), capability gap (local expertise), and competitive threat (Paystack becoming a regional rival). This move accelerated Stripe’s global expansion without diverting focus from its core business.

Before diving into why deals happen, two questions deserve attention: Why should founders consider being acquired? And why is now the right time to consider this?

Successful acquisitions can serve as catalysts

Why does the current macro environment favor acquisitions?

For some, it's about liquidity upon exit. For others, it's access to durable distribution channels, ensuring long-term viability, or becoming part of a platform that amplifies impact. For many, it's a way to bypass the increasingly narrow venture capital route—VC funding is scarcer than ever, investor expectations are higher, and time is tighter.

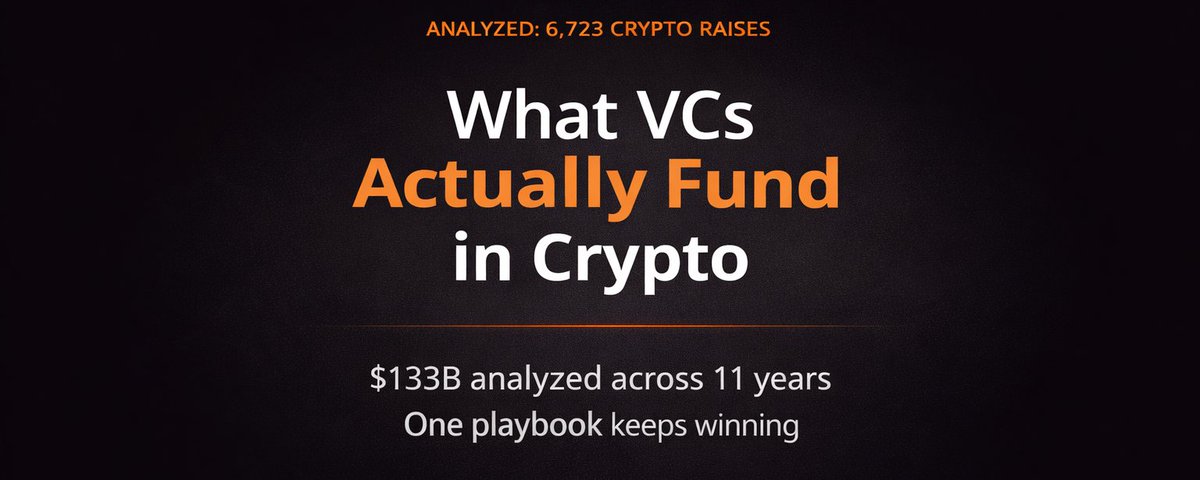

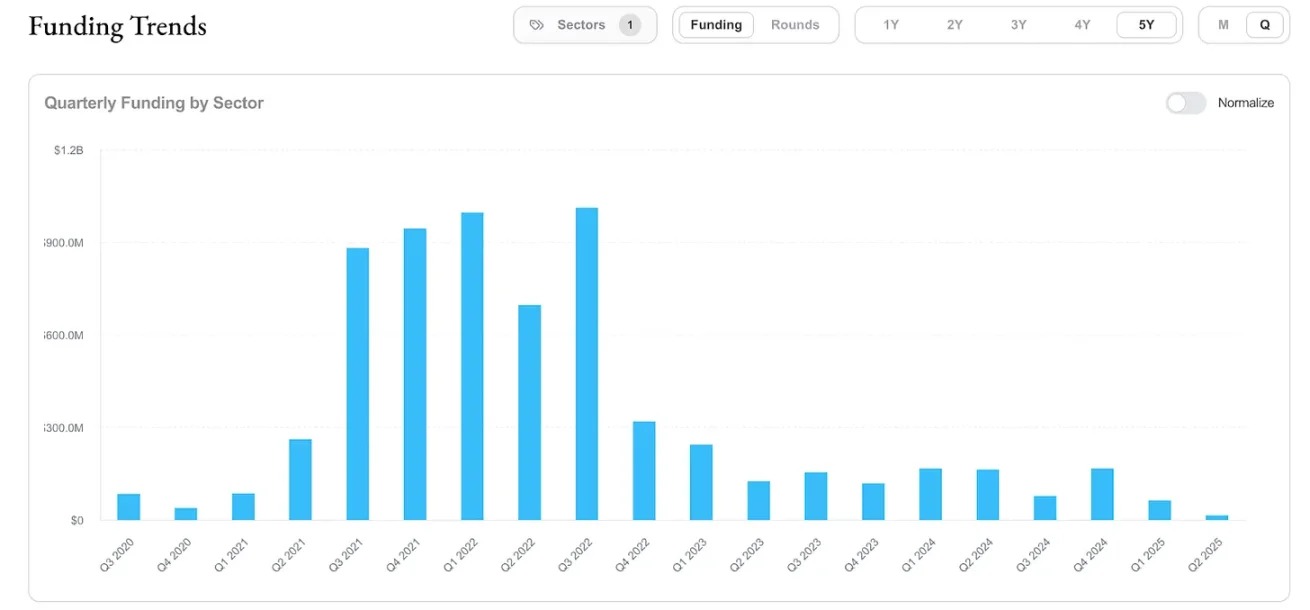

A rising tide doesn’t lift all boats

The venture capital market lags public markets by several quarters. Typically, after Bitcoin reaches a peak, VC activity takes months or even quarters to cool down. Venture investment in crypto has declined by over 70% since its 2021 peak, with median valuations returning to 2019–2020 levels. I don't believe this is a temporary correction.

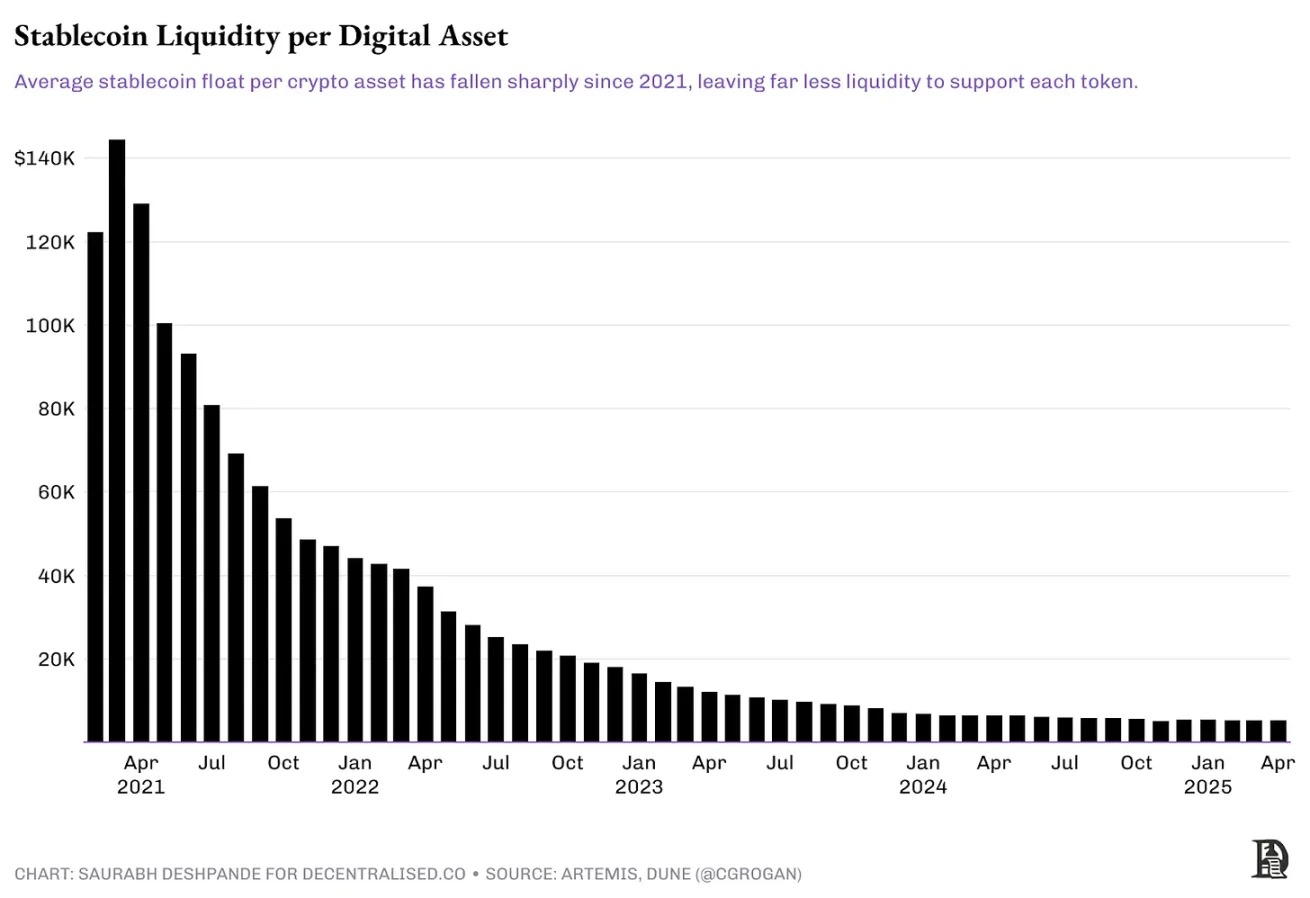

Here’s why. Simply put, VC returns have declined while the cost of capital has risen. As a result, with higher opportunity costs, less venture capital chases deals. From a crypto-specific standpoint, market structure has been affected by the massive increase in asset supply. Most token businesses should pay attention to this chart. Just because it's easy to launch a new token doesn’t mean you should. Capital online is finite. With every new asset launched, the liquidity chasing it diminishes, as shown below.

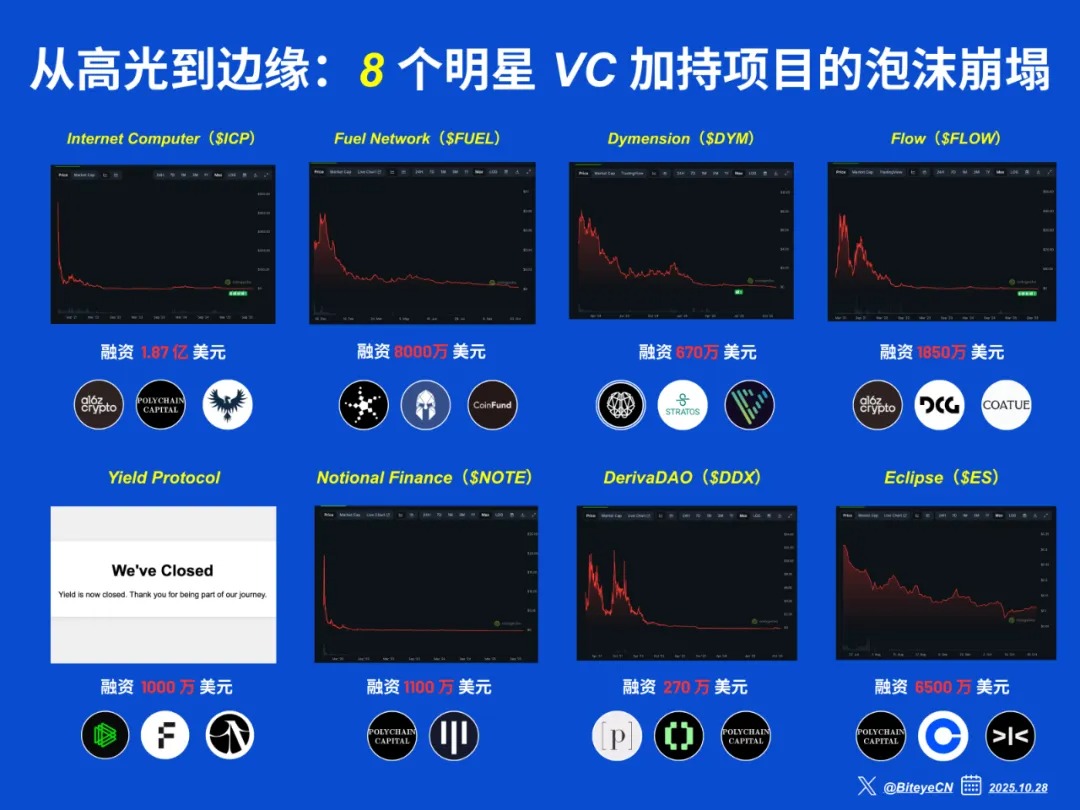

Every VC-backed token launched with a high fully diluted valuation (FDV) requires substantial liquidity to reach a multibillion-dollar market cap. For example, EigenLayer’s EIGEN token launched at $3.90 with a $6.5 billion FDV. At launch, circulating supply was about 11%, giving it a market cap of ~$720 million. Today, circulating supply is ~15%, with an FDV of ~$1.4 billion. After multiple unlock rounds, 4% of supply has entered circulation since TGE. Since launch, the token price has dropped ~80%. To return to its initial valuation amid increased supply, the price would need to rise 400%.

Unless tokens actually accumulate value, there's little reason for market participants to chase them—especially in a market flooded with investment options. Most of these tokens may never return to their initial valuations. I reviewed the 30-day revenue of all projects on Token Terminal and found only three (Tether, Tron, and Circle) generate over $1 million monthly. Only 14 generate over $100,000 monthly. Of those 14, eight have tokens with actual investment value.

This means individual investors either can’t exit or must do so at a discount. Poor secondary market performance pressures VC returns, leading to more cautious investment strategies. Therefore, products must either achieve product-market fit (PMF) or represent something entirely novel to attract investors and earn valuation premiums. A startup with just an MVP and no users will struggle to find investors. So if you’re building another “blockchain scaling layer,” your chances of attracting top-tier investors are slim.

We’ve already seen this unfold. As noted in our Venture Funding Tracker, monthly VC inflows into crypto dropped from a peak of $23 billion in 2022 to $6 billion in 2024. Total funding rounds fell from 941 in Q1 2022 to 182 in Q1 2025, reflecting VC caution.

Why now?

So what comes next? Acquisition may make more sense than another funding round. Protocols or companies with existing revenue will pursue niche players that fill their blind spots. The current environment pushes teams toward consolidation. Higher interest rates make capital expensive; user adoption has plateaued, making organic growth harder; token incentives are less effective; and regulation forces teams to professionalize faster. All these factors push crypto toward acquisition as a growth strategy. This time, M&A activity in crypto appears more deliberate and focused than in previous cycles. We’ll explore why later.

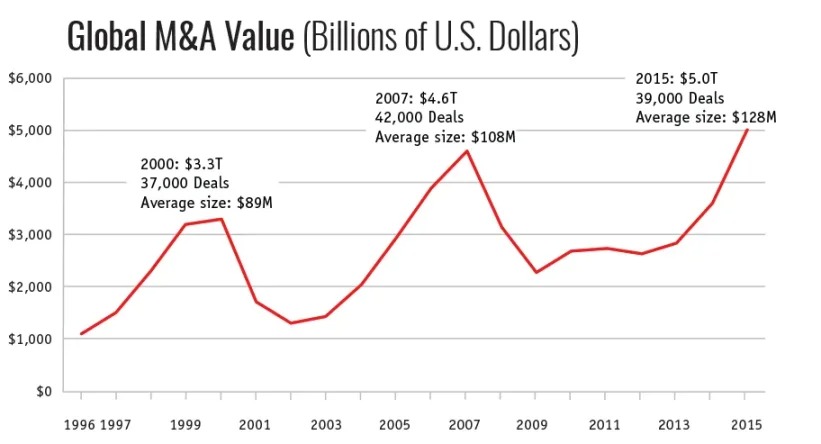

M&A cycles

Historically, traditional finance has seen five to six major waves of M&A, driven by deregulation, economic expansion, cheap capital, or technological change. Early waves were driven by vertical integration and monopolistic ambitions; later ones emphasized synergies, diversification, or global reach. We don’t need to delve into a century of M&A history—simply put: when growth slows and capital is abundant, consolidation accelerates.

Source: Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance

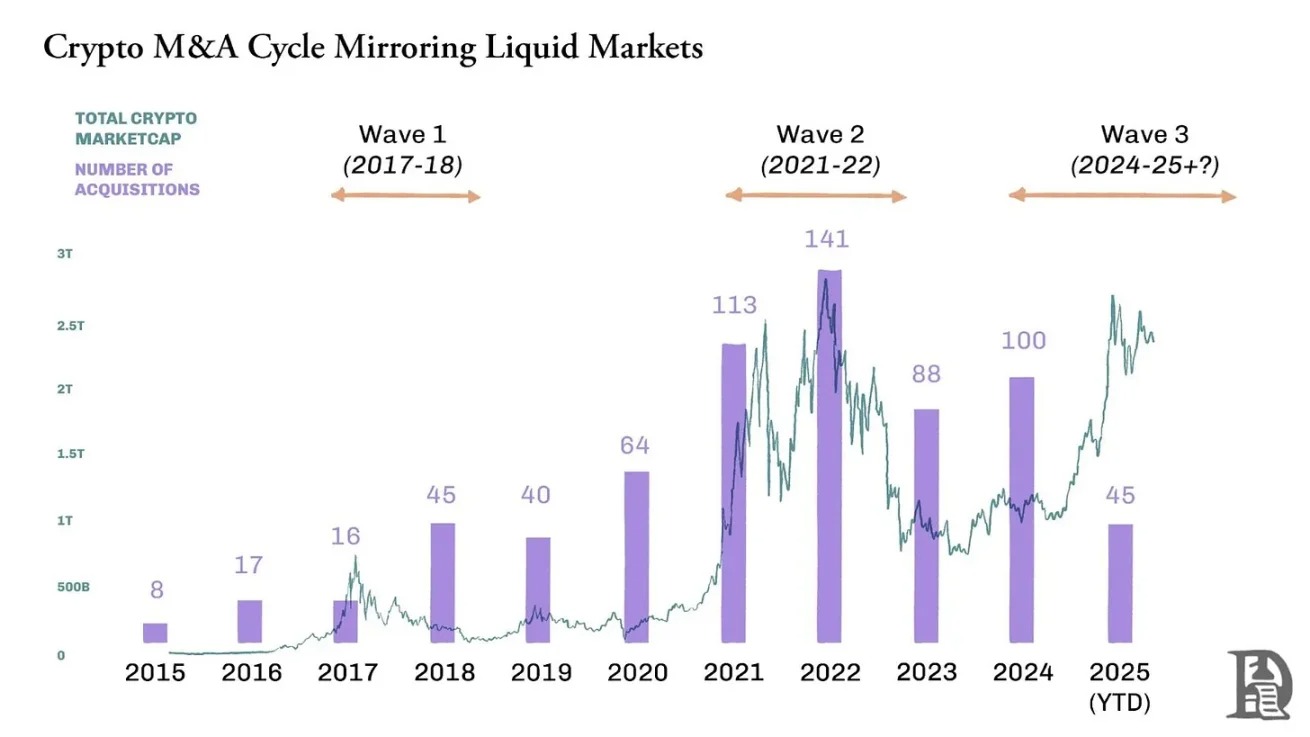

How can we interpret different stages of M&A in crypto? It mirrors what we’ve seen in traditional markets over decades. Growth in emerging industries tends to be wave-like, not linear. Each M&A wave reflects different needs along the industry maturity curve: from building products, to finding PMF, to acquiring users, and finally securing distribution, compliance, or defensive capabilities.

Source: CBInsights

We saw this during the early internet and mobile eras. Recall Google’s mid-2005 acquisition of Android—a strategic bet that mobile devices would become the dominant computing platform. As described in *Androids: The Team That Built the Android Operating System* by Chet Haase, a veteran Android engineer and Google employee:

In 2004, global PC shipments totaled 178 million units. Mobile phone shipments reached 675 million—nearly four times as many—but their processors and memory performed at 1998 PC levels.

The mobile OS market was fragmented and constrained. Microsoft charged licensing fees for Windows Mobile, Symbian ran mostly on Nokia devices, and BlackBerry’s OS was limited to its own hardware. This created a strategic opening for an open platform.

Google seized the opportunity by acquiring a free, open-source OS that manufacturers could adopt without costly licenses or building from scratch. This democratization allowed hardware makers to focus on strengths while accessing a sophisticated platform capable of competing with Apple’s tightly controlled iOS ecosystem. Google could have built an OS from scratch, but acquiring Android gave it a head start and helped counter Apple’s growing dominance. Twenty years later, 63% of web traffic comes from mobile devices, 70% of which runs on Android. Google foresaw the shift from PCs to mobile, and Android helped it dominate mobile search.

The 2010s were dominated by cloud infrastructure-related deals. Microsoft’s $26 billion acquisition of LinkedIn in 2016 aimed to integrate identity and professional data across Office, Azure, and Dynamics. Amazon’s 2015 acquisition of Annapurna Labs to develop custom chips and edge computing for AWS signaled that vertical integration of infrastructure was becoming crucial.

These cycles emerged because each stage of industry development introduced new constraints. Early on, speed to market mattered most. Later, user acquisition took priority. Ultimately, regulatory clarity, scalability, and sustainability became decisive. Acquisitions allow industry winners to compress time—buying licenses instead of applying, acquiring teams instead of hiring, purchasing infrastructure instead of building from scratch.

Thus, crypto’s M&A rhythm echoes traditional markets. The technology differs, but the logic remains the same.

Three waves of crypto M&A

Upon reflection, crypto M&A has gone through three distinct phases, each shaped by prevailing market demands and technological conditions.

First Wave (2017–2018)—ICO Boom: Smart contract platforms were emerging, DeFi didn’t exist yet, and the goal was simply to build on-chain apps that attracted users. Exchanges and wallets acquired smaller front-end platforms to capture new token holders. Notable deals from this era include Binance acquiring Trust Wallet and Coinbase acquiring Earn.com.

Second Wave (2020–2022)—Capital-Fueled Acquisitions: Protocols like Uniswap, Matic (now Polygon), and Yearn Finance, along with firms like Binance, FTX, and Coinbase, had achieved product-market fit (PMF). During the 2021 bull run, their valuations surged, leaving them flush with overvalued tokens to spend. Protocol DAOs used governance tokens to acquire related teams and technologies. Yearn’s acquisition spree, OpenSea’s purchase of Dharma, and FTX’s pre-collapse buying frenzy (e.g., LedgerX, Liquid) defined this era. Polygon also pursued ambitious acquisitions, buying Hermez (a zero-knowledge scaling solution) and Mir (zero-knowledge tech) to establish leadership in ZK scaling.

Third Wave (2024–Present)—Compliance and Scalability Phase: Amid tighter VC funding and clearer regulations, well-capitalized firms are snapping up teams that bring regulated venues, payment infrastructure, ZK talent, and account abstraction primitives. Recent examples include Coinbase acquiring BRD Wallet to strengthen its mobile wallet strategy and user onboarding, and FairX to accelerate its push into derivatives.

Robinhood acquired Bitstamp to expand internationally. Bitstamp holds over 50 active licenses and registrations globally, giving Robinhood access to customers in the EU, UK, US, and Asia. Stripe acquired OpenNode to deepen its crypto payment infrastructure.

Why do acquirers acquire?

Some startups are acquired for strategic reasons. When an acquirer initiates a deal, they typically aim to accelerate their roadmap, eliminate competitive threats, or expand into new user bases, technologies, or regions.

For founders, being an acquisition target isn’t just about financial return—it’s about scale and continuity. A well-executed acquisition can provide broader distribution, long-term resources, and the ability to embed products into a larger ecosystem. Rather than struggling through another funding round or pivoting to catch the next wave, being acquired may be the most effective way to fulfill a startup’s original mission.

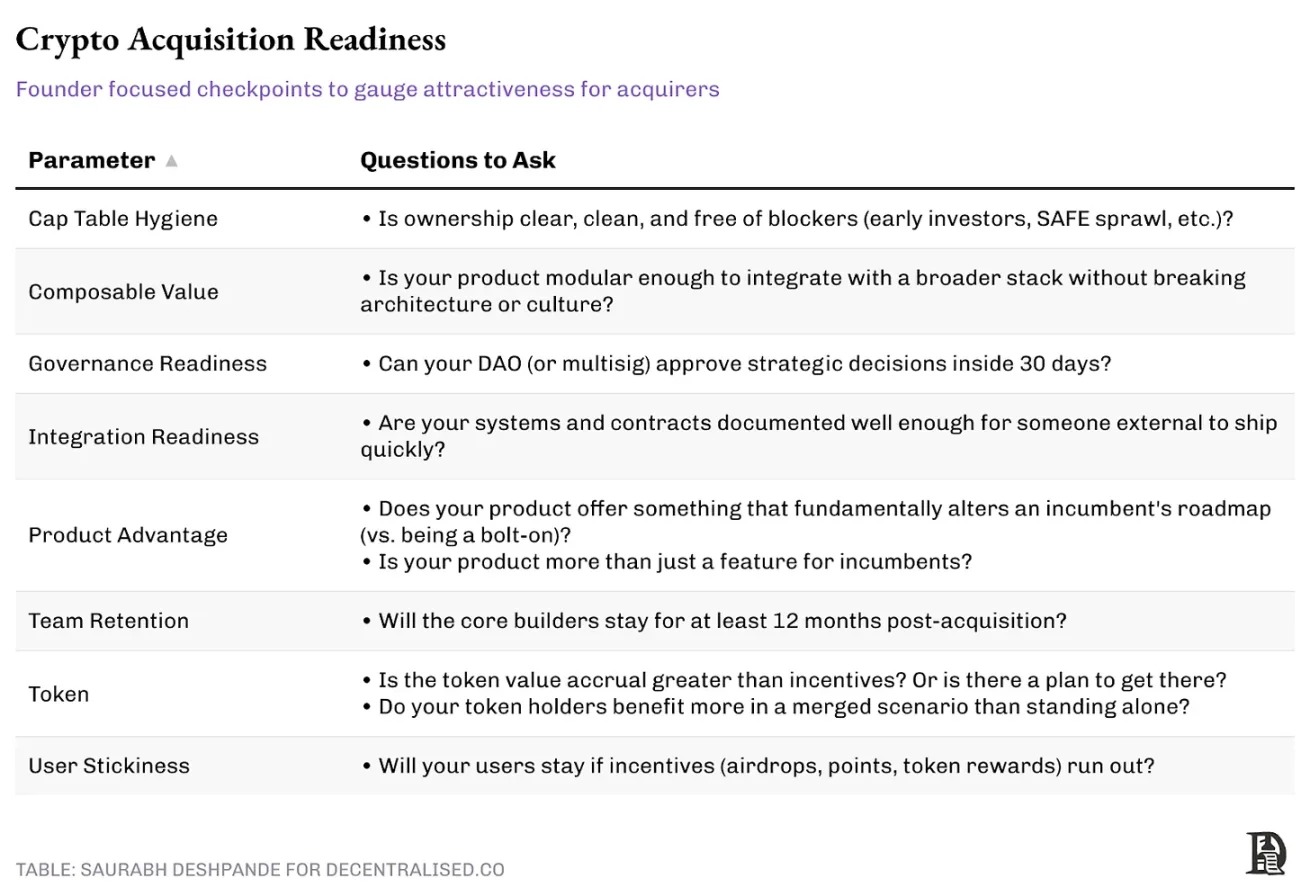

Below is a framework to assess how close your startup is to becoming a “compelling acquisition target.” Whether you’re actively considering an exit or just building with acquisition potential in mind, excelling in these parameters significantly increases your visibility to the right buyers.

Four models of crypto acquisitions

Analyzing major deals over recent years reveals clear patterns in structure and execution. Each model represents a different strategic emphasis:

1. Talent Acquisition

Vibe coding exists, but teams still need skilled engineers who can build without relying on AI. We haven’t reached the point where AI can write production code trusted with millions of dollars. Thus, acquiring small startups before they become threats to secure talent is a valid rationale for incumbents.

But why is talent acquisition economically rational? First, acquirers gain relevant IP, ongoing product lines, and existing user bases and distribution. For example, when ConsenSys acquired Truffle Suite in 2020, it gained not just a dev tool team but key IP like Truffle Boxes, Ganache, and Drizzle.

Second, talent acquisitions let incumbents rapidly integrate specialized teams at lower cost than building from scratch in a competitive labor market. As far as I know, there were only about 500 engineers truly versed in ZK tech in 2021. That’s why Polygon’s $400M acquisition of Mir Protocol and $250M purchase of Hermez Network made sense. Hiring those ZK cryptographers individually could have taken years.

Instead, these acquisitions instantly brought elite ZK researchers and engineers into Polygon’s fold, massively simplifying recruitment and onboarding. Compared to hiring, training, and ramp-up timelines, these deals were economically efficient—especially since the acquired teams were already shipping products.

When Coinbase acquired Agara for $40–50 million at the end of 2021, the deal was more about engineering talent than customer service automation. Agara’s India-based team had deep expertise in AI and NLP. Post-acquisition, many of these engineers joined Coinbase’s product and ML teams to support its broader AI initiatives.

Though framed as tech acquisitions, the real assets were people: engineers, cryptographers, and protocol designers capable of realizing Polygon’s ZK vision. While full integration and productization took longer than expected, these deals gave Polygon a deep bench of ZK talent—a strategic advantage that continues to shape its competitive stance.

2. Capability / Ecosystem Expansion

Some strategic acquisitions focus on expanding ecosystem coverage or internal capabilities. The acquirer’s positioning and market reputation often aid this effort.

Coinbase exemplifies capability expansion through acquisition. Its 2019 acquisition of Xapo expanded its custody offerings, laying the foundation for Coinbase Custody—a secure, compliant digital asset storage solution. The 2020 purchase of Tagomi led to Coinbase Prime, a comprehensive suite of institutional trading and custody services. Acquiring FairX in 2022 and Deribit in 2025 helped solidify Coinbase’s position in U.S. and global derivatives markets.

Consider Jupiter’s early 2025 acquisition of Drip Haus. Jupiter, Solana’s leading decentralized exchange aggregator, aims to expand from DeFi into NFTs. Drip Haus built a highly active on-chain audience by offering creators free NFT collection distribution on Solana.

Given Jupiter’s tight integration with Solana’s infrastructure and developer ecosystem, it has unique insights into trending cultural content. It viewed Drip Haus as a key attention hub, especially within creator communities.

By acquiring Drip Haus, Jupiter gained a foothold in creator economies and community-driven NFT distribution. This allows it to extend NFT functionality to broader audiences and offer NFTs as incentives to traders and liquidity providers. It’s not just about collectibles—it’s about owning Solana-native NFT channels that command attention. This ecosystem expansion marks Jupiter’s first foray into culture and content, areas it previously hadn’t touched—mirroring how Coinbase systematically built custody, prime brokerage, derivatives, and asset management via acquisitions.

Source: Bloomberg

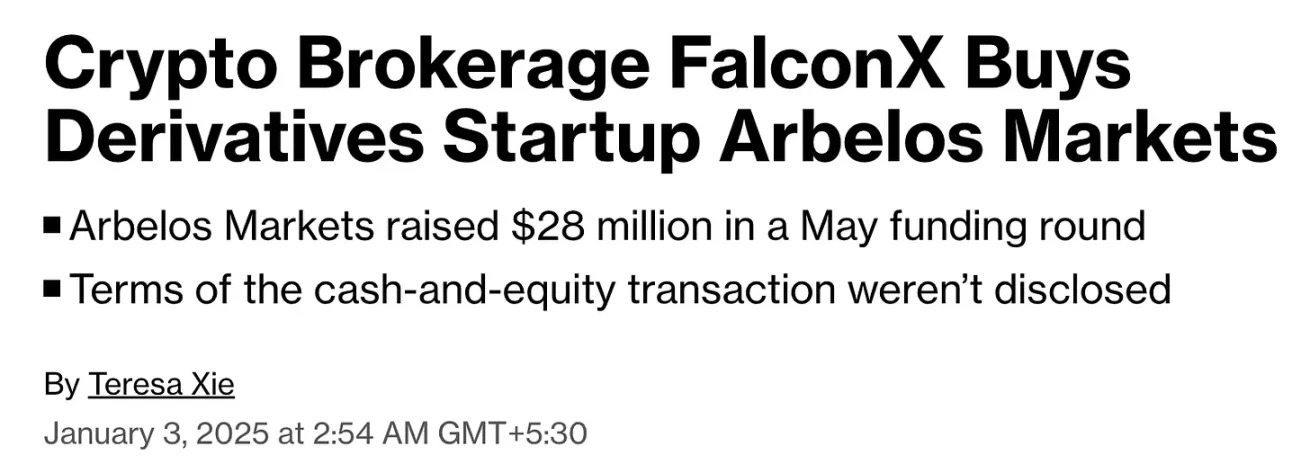

Another example is FalconX’s April 2025 acquisition of Arbelos Markets. Arbelos is a specialist trading firm known for expertise in structured derivatives and risk warehousing—capabilities critical for serving institutional clients. As a primary broker for institutional crypto flows, FalconX understood Arbelos’ derivatives volume firsthand, likely reinforcing its view of Arbelos as a high-value target.

By bringing Arbelos in-house, FalconX enhanced its ability to price, hedge, and manage risk for complex crypto instruments. This acquisition strengthens core infrastructure to attract and retain sophisticated institutional capital.

3. Infrastructure Distribution

Beyond talent, ecosystems, or users, some acquisitions center on infrastructure distribution. They embed a product into a broader stack to improve defensibility and market reach. A clear example is ConsenSys’ 2021 acquisition of MyCrypto. While MetaMask was already the leading Ethereum wallet, MyCrypto brought UX experimentation, security tools, and a different user base focused on advanced users and long-tail assets.

This wasn’t a full rebrand or merger—both teams continued parallel development. Eventually, MyCrypto’s feature set was integrated into MetaMask’s codebase. This strengthened MetaMask’s market position and defended against more agile wallet competitors by directly absorbing innovation.

Such infrastructure-driven acquisitions aim to lock in users at critical layers by improving tooling stacks and protecting distribution channels.

4. User Base Acquisition

Finally, the most direct strategy: buying users. This is especially evident in NFT marketplace competition, where battles for collectors are fierce.

OpenSea’s April 2022 acquisition of Gem is illustrative. At the time, Gem had ~15,000 weekly active wallets. For OpenSea, this was a preemptive defense: locking in a high-value cohort of “pro” users and accelerating development of an advanced aggregator interface, later launched as OpenSea Pro. In competitive markets, acquisition is more cost-effective when speed matters. The lifetime value (LTV) of these users—especially NFT “pros” who spend heavily—is likely sufficient to justify the acquisition cost.

Acquisition only makes economic sense when justified. Industry benchmarks show average 2024 NFT user revenue at $162. But Gem’s core “pro” users likely generated orders of magnitude more. Conservatively estimating $10,000 LTV per user implies $150 million in value. If OpenSea paid under $150 million, the deal likely broke even purely on user economics—not to mention saved development time.

While user-centric acquisitions lack the glamour of talent- or tech-driven deals, they remain one of the fastest ways to consolidate network effects.

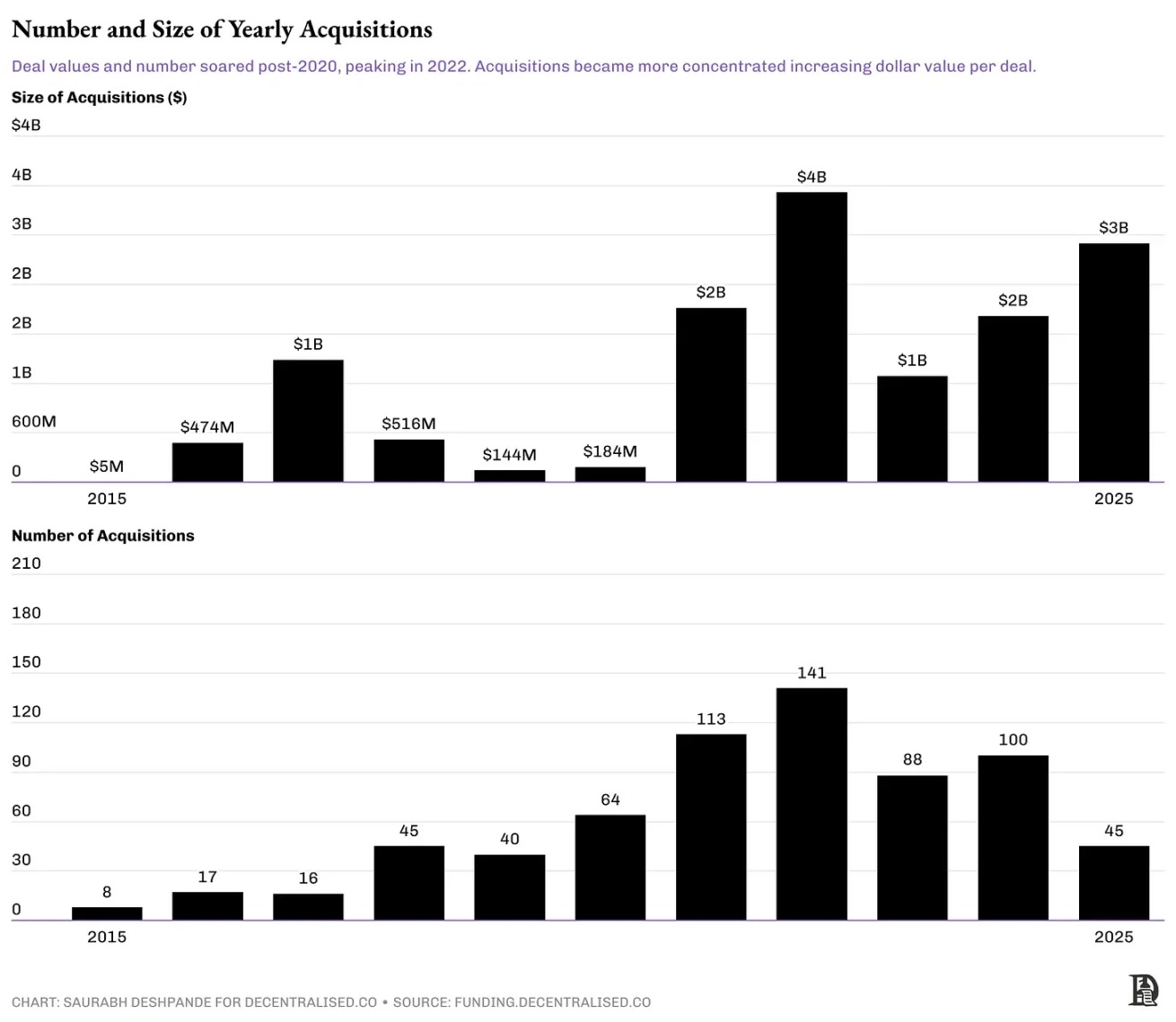

What do the numbers tell us?

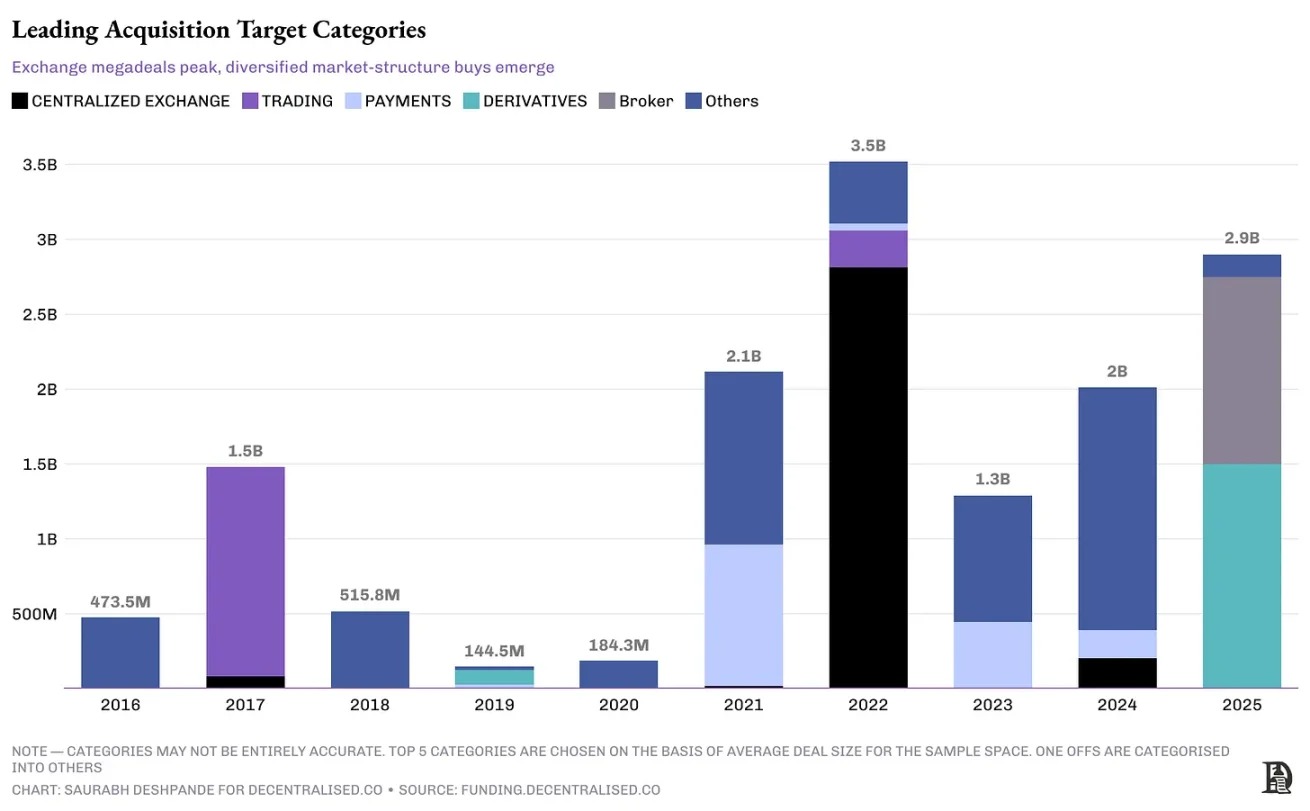

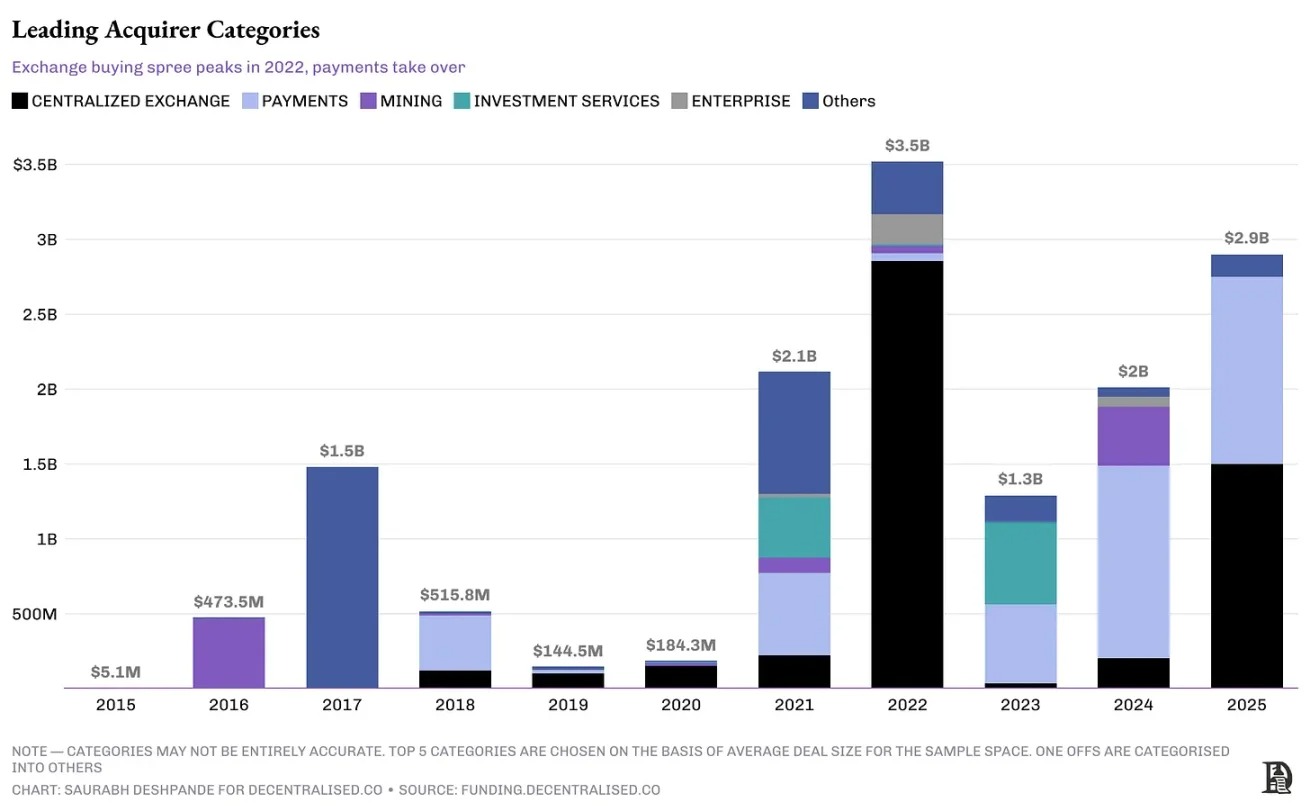

Below is a macro view of crypto M&A evolution over the past decade—broken down by volume, acquirers, and target categories.

As noted earlier, deal volume doesn’t perfectly align with public market price movements. In the 2017 cycle, Bitcoin peaked in December, but M&A momentum continued into 2018. A similar lag occurred this time: Bitcoin peaked in November 2021, but crypto M&A peaked in 2022. Private markets react slower, often digesting trends with delay.

Post-2020, M&A activity surged, peaking in both volume and cumulative value in 2022. But volume alone doesn’t tell the full story. Though M&A cooled in 2023, the scale and nature of deals changed. Broad defensive buying has given way to more selective category investments. Interestingly, despite fewer deals post-2022, total transaction value rebounded in 2025. This suggests the market isn’t shrinking—rather, mature acquirers are making fewer, larger, and more targeted deals. Average deal size rose from $25 million in 2022 to $64 million in 2025.

Coinbase’s Deribit deal not included in this chart

In terms of target categories, early M&A targets were scattered. Marketplaces acquired gaming assets, rollup infrastructure, and made ecosystem bets spanning early games, Layer 2 infrastructure, and wallet integrations. Over time, however, target categories have become more concentrated. At the 2022 M&A peak, deals focused on acquiring trading infrastructure—matching engines, custody systems, and front-end interfaces needed to enhance trading platforms. Recently, M&A has centered on derivatives and user-facing brokerage channels.

Coinbase’s Deribit deal not included in this chart

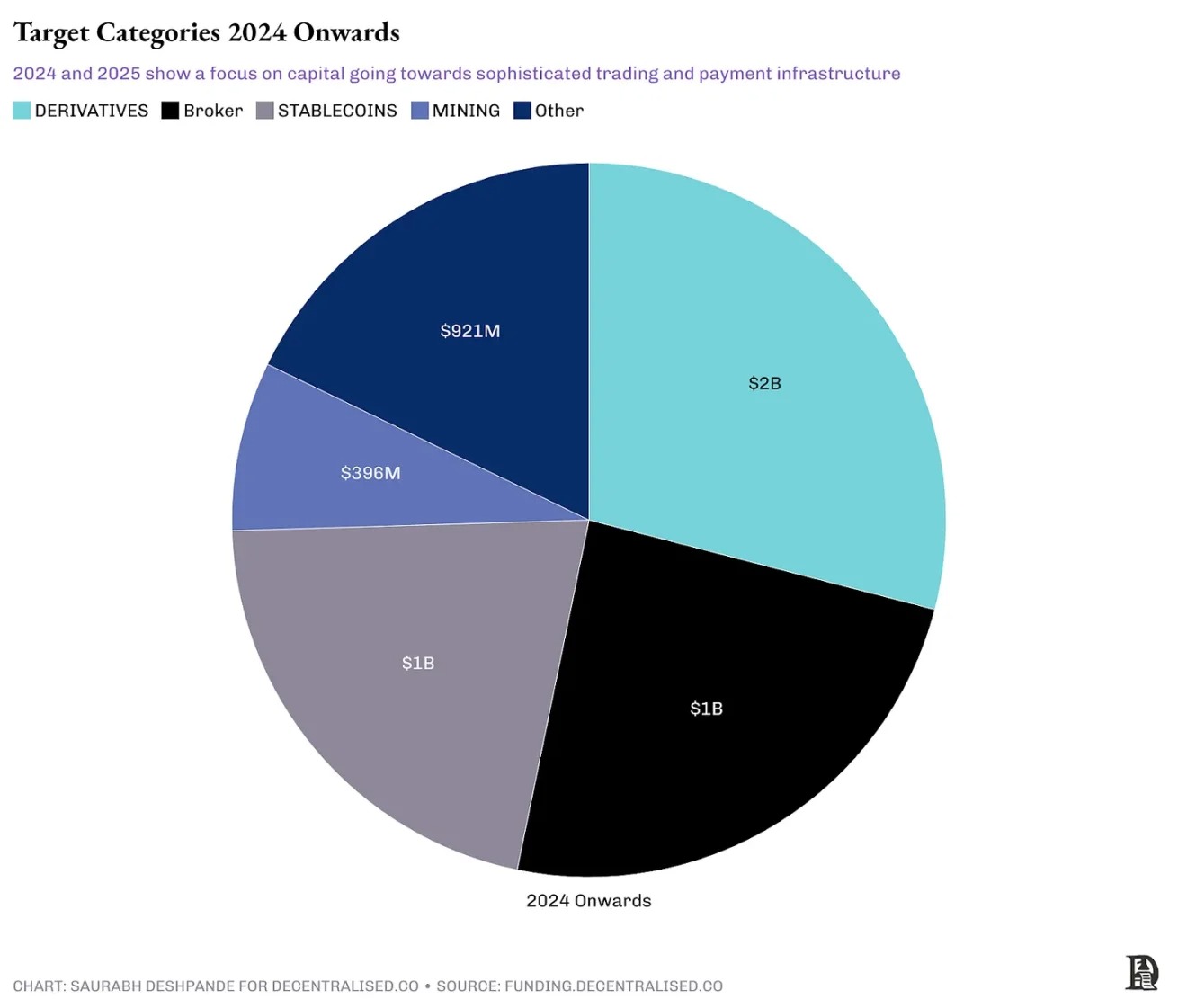

Diving deeper into 2024–2025 deals reveals rising concentration. Derivatives exchanges, brokerage channels, and stablecoin issuers absorbed over 75% of disclosed deal value. Clearer CFTC rules on crypto futures, MiCA’s green light for stablecoins, and Basel guidelines on reserve assets reduced risks in these areas. Giants like Coinbase responded by buying regulatory footholds instead of building them. NinjaTrader gave Kraken necessary licenses and 2 million U.S. customers. Bitstamp provides MiCA-compliant trading coverage, while OpenNode connects USD stablecoin rails directly into Stripe’s merchant network.

Coinbase’s Deribit deal not included in this chart

Acquirers are also evolving. In 2021–2022, exchanges led M&A by acquiring infrastructure, wallets, and liquidity layers to defend market share. By 2023–2024, the baton passed to payment firms and financial tool platforms targeting downstream products like NFT channels, brokers, and structured product infrastructure. But with regulatory shifts and underserved derivatives markets, exchanges like Coinbase and Robinhood have reemerged as acquirers, buying derivatives and brokerage infrastructure.

A common trait among these acquirers is ample capital. By end-2024, Coinbase held over $9 billion in cash and equivalents. Kraken generated $454 million in operating profit in 2024. Stripe had over $2 billion in free cash flow in 2024. Most acquirers, by deal value, are profitable. Kraken’s acquisition of NinjaTrader to control the entire futures trading stack—from UI to settlement—is an example of vertical integration aimed at capturing more of the value chain. In contrast, horizontal acquisitions expand market reach at the same level—Robinhood’s Bitstamp purchase to broaden geography is a case in point. Stripe’s OpenNode acquisition combines vertical and horizontal integration.

Coinbase’s Deribit deal not included in this chart

Remember Google’s Android story? Google prioritized two things over short-term revenue, simplifying the mobile experience for hardware makers and software creators. First, providing a unified system for hardware manufacturers to adopt—eliminating fragmentation plaguing the mobile ecosystem. Second, offering a consistent software programming model so developers could build apps running across all Android devices.

We see similar patterns in crypto. Well-funded incumbents aren’t just filling gaps—they’re strengthening market positions. Examining recent deals reveals a gradual strategic shift in both targets and acquirers. The key takeaway: we’re seeing signs of industry maturation. Exchanges are fortifying moats, payment firms race to own channels, miners bolster operations ahead of halving, and hype-driven verticals like gaming have quietly vanished from M&A records. The industry is beginning to understand which integrations create compounding effects—and which merely burn capital.

Gaming is a telling example. Between 2021–2022, investors poured billions into game-related startups. Since then, investment has sharply slowed. As Arthur noted on our podcast, investors have lost interest in gaming unless clear PMF exists.

Source: funding.decentralised.co

This context helps explain why so many M&A deals—despite strategic intent—fail to deliver. It’s not just about what was acquired, but how well it was integrated. While crypto is unique in many ways, it’s not immune to these pitfalls.

Why M&A often fails

In *The M&A Failure Trap*, Baruch Lev and Feng Gu studied 40,000 global M&A cases, concluding that 70%–75% fail. They attribute failure to factors like target companies being too large, overvaluation, unrelated-to-core-business acquisitions, weak target operations, and misaligned executive incentives.

Crypto has seen failed M&A cases where these factors apply. Take FTX’s $150 million 2020 acquisition of portfolio tracker Blockfolio. At the time, the deal was touted as strategic—converting Blockfolio’s 6 million retail users into FTX traders. Though the app was rebranded FTX App and briefly gained traction, it failed to meaningfully boost retail trading volume.

Worse, when FTX collapsed in late 2022, the Blockfolio partnership virtually disappeared. Years of brand equity vanished overnight. This shows that even acquisitions with strong user bases can evaporate due to platform-wide failure.

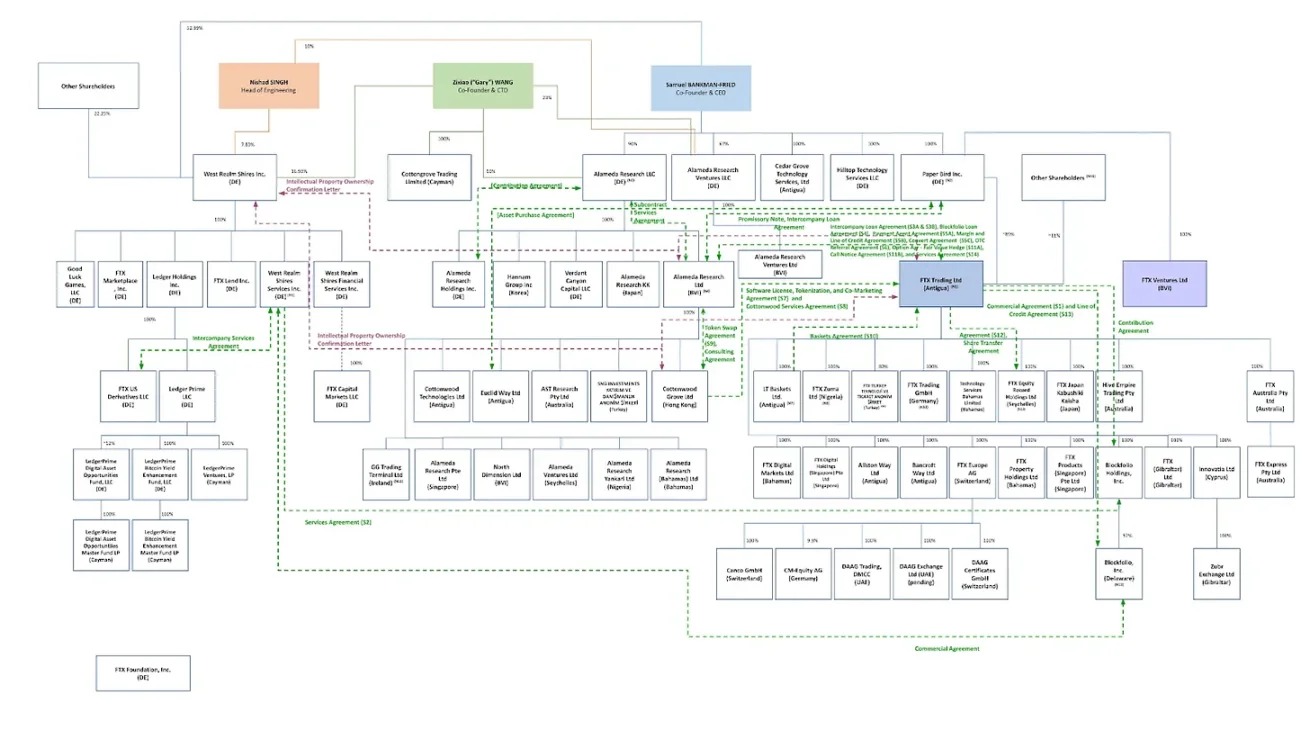

Many companies move too fast and make mistakes. The image below shows how quickly FTX acquired entities—perhaps unnecessarily so. It acquired licenses through purchases; the diagram shows its post-acquisition corporate structure.

Source: Financial Times

Polygon stands out as a case highlighting the risks of aggressive acquisition. Between 2021 and 2022, it spent nearly $1 billion acquiring ZK-related projects like Hermez and Mir Protocol. At the time, these moves were praised as visionary. But two years later, these investments haven’t translated into meaningful user adoption or market leadership. One of its flagship ZK projects, Miden, eventually spun off as an independent company in 2024. Once central to crypto discourse, Polygon has significantly declined in strategic relevance. Of course, such things take time—but to date, there’s little evidence of ROI from these acquisitions. Polygon’s buying spree reminds us that even well-funded talent-driven acquisitions can fail without proper timing, integration, and clear downstream use cases.

Native on-chain DeFi has also seen failed acquisitions. In 2021, Fei Protocol and Rari Capital merged via token swap and joint governance under the newly formed Tribe DAO. In theory, the merger promised deeper liquidity, lending integration, and DAO collaboration. But the merged entity quickly faced governance disputes, suffered a costly Fuse market exploit, and ultimately voted to return funds to token holders.

Nonetheless, crypto holds three advantages over traditional industries in successful M&A:

-

Open-source foundations mean technical integration is usually easier. When most code is already public, due diligence is more straightforward, and merging codebases presents fewer issues than combining proprietary systems.

-

Tokenomics can create incentive alignment mechanisms unmatched by traditional equity—provided tokens have real utility and value capture. When teams from both sides hold tokens in the merged entity, their incentives stay aligned long after the deal closes.

-

Community governance introduces accountability mechanisms rare in traditional M&A. When major changes require token holder approval, deals driven solely by executive hubris become harder to execute.

So where do we go from here?

Build to be acquired

The current funding environment demands pragmatism. If you're a founder, your pitch shouldn't just be “why we should raise,” but “why someone might acquire us.” Below are the three main drivers shaping today’s crypto M&A landscape.

First, venture capital will be more precise

Funding conditions have shifted. VC investment has plummeted over 70% from its 2021 peak. Monad’s $225 million Series A and Babylon’s $70 million seed round are outliers, not signs of market recovery. Most VCs now focus on companies with traction and clear business models. With higher interest rates raising capital costs and most tokens failing to demonstrate sustainable value accrual, investors are extremely selective. For founders, this means considering acquisition offers alongside increasingly difficult fundraising paths.

Second, strategic leverage

Well-funded incumbents are buying time, distribution, and defensibility. As regulatory clarity improves, licensed entities become prime acquisition targets. But this appetite extends further. Companies like Coinbase, Robinhood, Kraken, and Stripe are acquiring to enter new regions faster, gain stable user bases, or compress years of infrastructure development into a single deal. If what you build reduces legal risk, accelerates compliance, or gives acquirers a clearer path to profitability or reputational gains, you’re already on their radar.

Third, distribution and interfaces

The missing piece in infrastructure is reliably and quickly delivering products to users. The key is acquiring components that unlock distribution, simplify complexity, and shorten time-to-market fit. Stripe acquired OpenNode to streamline crypto payments. Jupiter bought DRiP Haus to add NFT distribution to its liquidity stack. FalconX acquired Arbelos to add institutional-grade structured products, potentially enabling service to broader client segments. These are infrastructure strategies aimed at expanding reach and reducing operational friction. If what you build enables other companies to grow faster, reach farther, or serve better, you’re on the buyer’s shortlist.

This is an era of strategic exits. Build your company with the understanding that your future depends on whether others want what you’ve built.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News