a16z Partner’s Self-Reflection: Boutique VCs Are Dead—Scaling Up Is the Endgame for VCs

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

a16z Partner’s Self-Reflection: Boutique VCs Are Dead—Scaling Up Is the Endgame for VCs

“The VC industry is undergoing a paradigm shift—from being driven by ‘judgment’ to being driven by ‘deal-winning capability.’”

Author: Erik Torenberg

Translation & Editing: TechFlow

TechFlow Intro: In the traditional narrative of venture capital (VC), the “boutique” model is often celebrated—scaling up is seen as compromising soul and authenticity. Yet in this essay, a16z partner Erik Torenberg mounts a forceful counterargument: with software now the backbone of the U.S. economy—and the dawn of the AI era—the needs of startups for capital and services have undergone a qualitative shift.

He argues that the VC industry is undergoing a paradigm shift—from being “judgment-driven” to being “deal-winning-driven.” Only “mega-institutions” like a16z, equipped with scalable platforms and capable of delivering comprehensive support to founders, can prevail in trillion-dollar contests.

This isn’t just an evolution of models—it’s the VC industry’s self-evolution amid the “software-eats-the-world” wave.

Full Text Below:

In classical Greek literature, there exists a meta-narrative above all others: reverence for the divine versus hubris—disregard for the sacred order. Icarus was burned by the sun not fundamentally because he was too ambitious, but because he disrespected the divine order. A more recent example is professional wrestling: ask “Who respects wrestling, and who disrespects it?” and you instantly distinguish the face (hero) from the heel (villain). All great stories adopt one form or another of this dichotomy.

VC has its own version of this story. It goes like this: “VC used to be—and always should be—a boutique business. Large institutions have grown too big and aim too high. Their downfall is inevitable, because their approach constitutes hubris toward the game itself.”

I understand why people want this story to hold true. But reality has changed—and so has venture capital.

Today, there’s more software, more leverage, and more opportunity than ever before. More founders are building larger-scale companies. Companies stay private longer. And founders’ expectations of VCs have risen dramatically. Today’s top founders don’t need passive check-writers waiting on outcomes—they need partners ready to roll up their sleeves and help them win.

Thus, the primary goal of today’s VC firms is to build the best interface for helping founders win. Everything else—how to staff, how to deploy capital, how large a fund to raise, how to support deal execution, how to empower founders—is derivative of that core objective.

Mike Maples famously said: “Your fund size is your strategy.” Equally true is: “Your fund size is your belief about the future.” It’s your bet on the scale of startup output. Raising massive funds over the past decade may have seemed “arrogant,” but that belief was fundamentally correct. So when top-tier firms continue raising enormous funds to deploy over the next decade, they’re betting on the future—and backing that bet with real capital. Scaled venture isn’t a corruption of the VC model; it’s the VC model finally maturing—and adopting the very traits of the companies it supports.

Yes, Venture Capital Is an Asset Class

In a recent podcast, Sequoia’s legendary investor Roelof Botha laid out three points. First, although VC is scaling, the number of “winning” companies each year remains fixed. Second, scaling VC means too much capital chasing too few great companies—so VC cannot scale; it is not an asset class. Third, the VC industry should shrink to match the actual number of winning companies.

Roelof is one of the greatest investors of all time—and a genuinely good person. But I disagree with him here. (It’s worth noting, of course, that Sequoia itself has scaled: it’s among the world’s largest VC firms.)

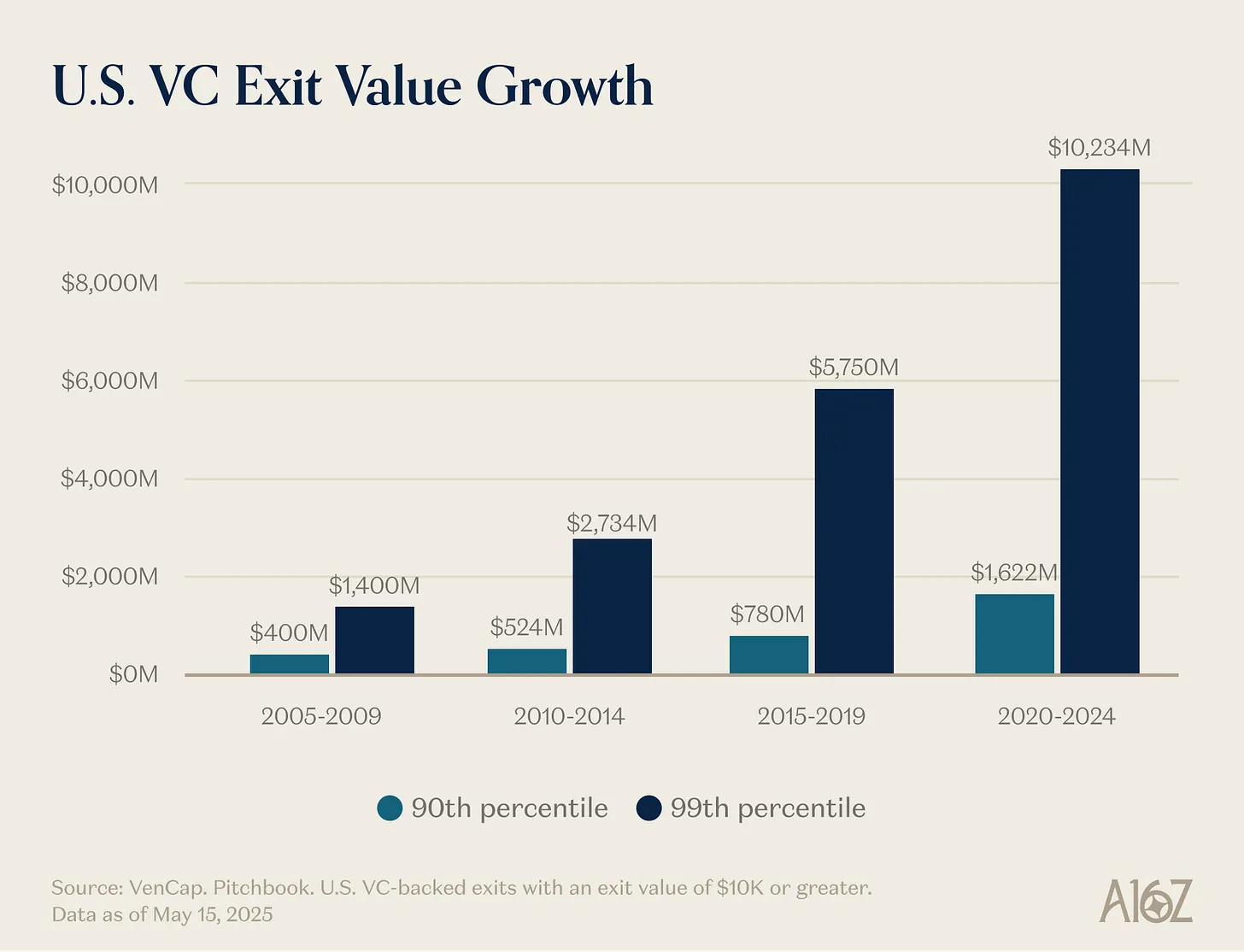

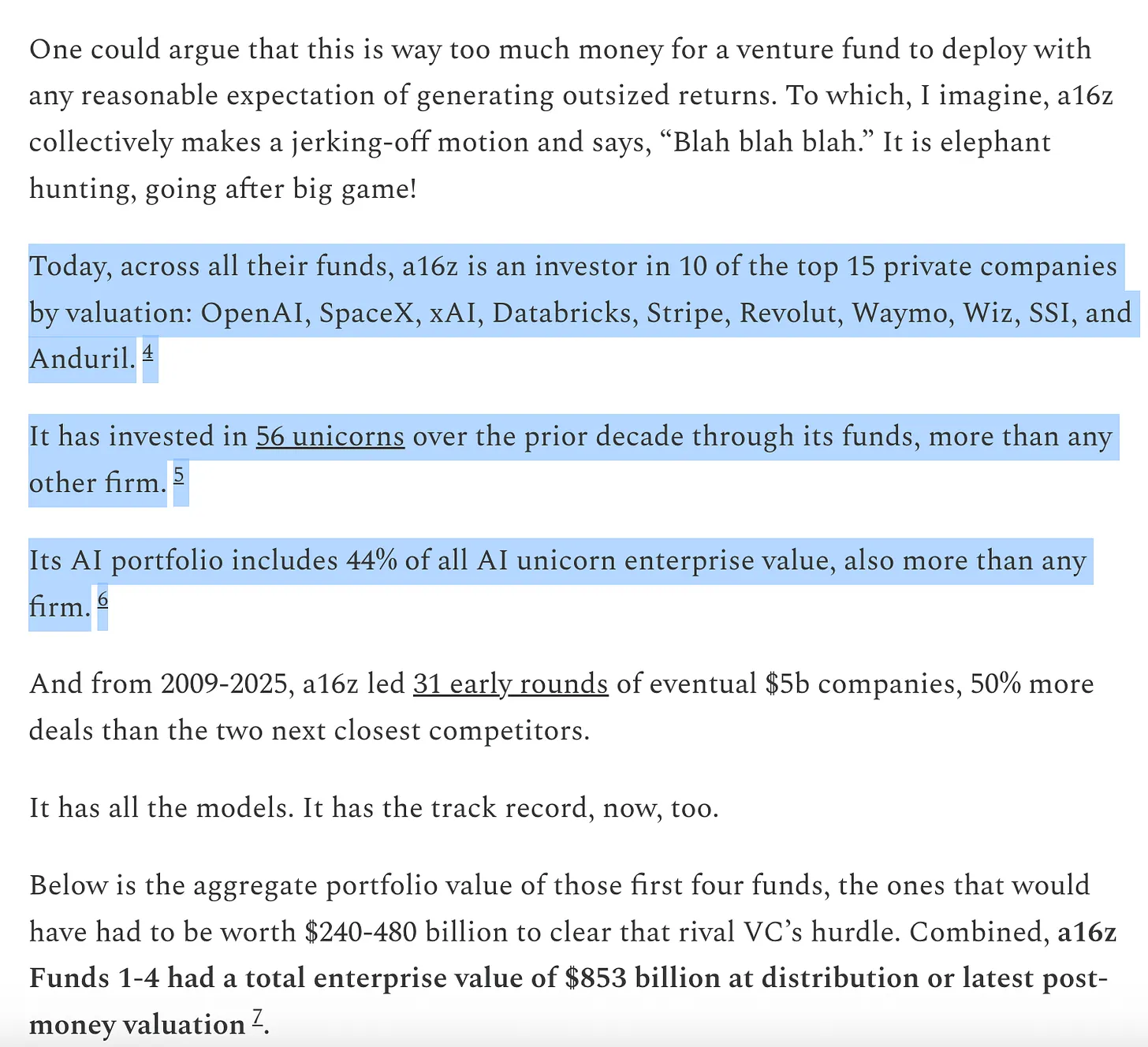

His first point—that the number of winners is fixed—is easily falsifiable. Roughly 15 companies reached $100M in revenue annually a decade ago; today, that number is ~150. Not only are there more winners—but they’re bigger, too. While entry prices have risen, output is vastly greater than before. The ceiling for startup scale has risen from $1B to $10B—and now to $1T and beyond. In the 2000s and early 2010s, YouTube and Instagram were considered billion-dollar acquisitions—so rare that we dubbed $1B+ companies “unicorns.” Today, we simply assume OpenAI and SpaceX will become trillion-dollar companies—and several more will follow.

Software is no longer a fringe, quirky corner of the U.S. economy. Software is the U.S. economy. Our largest companies—our national champions—are no longer General Electric and ExxonMobil, but Google, Amazon, and Nvidia. Private tech firms now represent 22% of the S&P 500. Software hasn’t finished eating the world—in fact, thanks to AI acceleration, it’s just getting started—and it’s more important than it was fifteen, ten, or even five years ago. So the potential scale of a successful software company is far greater than before.

The definition of a “software company” has also shifted. Capex has surged—large AI labs are becoming infrastructure companies, owning their own data centers, power generation facilities, and chip supply chains. Just as every company became a software company, now every company is becoming an AI company—and perhaps an infrastructure company, too. More and more firms are entering the atomic world. Boundaries are blurring. Companies are aggressively vertically integrating—and the market potential of these vertically integrated tech giants dwarfs anything imagined for pure software companies.

This leads directly to why the second point—that too much money chases too few companies—is wrong. Output is vastly larger than before; competition across the software landscape is fiercer than ever; and companies go public much later. All of this means great companies need to raise far more capital than before. VC exists to invest in new markets—and time and again, we learn that new markets end up far larger than anyone expected. The private markets have matured enough to support top-tier companies reaching unprecedented scale—as evidenced by the liquidity available to today’s top private companies. Both private and public market investors now believe VC output will be staggering. We’ve consistently underestimated how large VC, as an asset class, can—and should—become. VC is scaling to catch up with that reality—and with the expanding opportunity set. The new world demands flying cars, global satellite constellations, abundant energy, and intelligence so cheap it’s free.

The reality is that many of today’s best companies are capital-intensive. OpenAI spends billions on GPUs—far more compute infrastructure than anyone imagined possible. Periodic Labs must build automated labs at unprecedented scale to drive scientific innovation. Anduril must build the future of defense. And all these companies must recruit and retain the world’s best talent in the most competitive talent market in history. The new generation of large winners—OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, Anduril, Waymo, and others—are capital-intensive and raised massive initial rounds at high valuations.

Modern tech companies typically require hundreds of millions of dollars because the infrastructure needed to build world-changing frontier technology is extraordinarily expensive. In the dot-com bubble era, a “startup” entered a blank slate, anticipating consumer demand still waiting for dial-up connections. Today, startups enter an economy shaped by thirty years of tech giants. Supporting “little tech” means arming David to fight a handful of Goliaths. Yes, companies in 2021 were overfunded—much of that capital flowed into sales and marketing for products that weren’t 10x better. But today, capital flows into R&D or capex.

So winners are far larger than before—and need to raise far more capital, often from day one. Thus, the VC industry must logically grow much larger to meet this demand. Given the size of the opportunity set, this scaling is justified. If VC had scaled beyond what its underlying opportunities warranted, we’d see the largest firms delivering poor returns. But we haven’t seen that at all. Even while scaling, top-tier VCs have repeatedly delivered exceptional multiples—and so have the LPs fortunate enough to gain access. A famous VC once claimed a $1B fund could never deliver a 3x return: “It’s too big.” Since then, some firms have surpassed 10x on a single $1B fund. Some point to underperforming firms to indict the asset class—but any power-law industry inevitably features massive winners and long-tail losers. The ability to win deals without relying solely on price is what enables sustained returns. In other major asset classes, you sell product to—or lend to—the highest bidder. But VC is uniquely competitive across dimensions beyond price. VC is the only asset class where top decile firms show significant persistence.

Last, the idea that the VC industry “should shrink” is also wrong—or at least, harmful for the tech ecosystem, for the goal of creating more generational tech companies, and ultimately for the world. Some complain about second-order effects of increased VC funding (and yes, there are some!), but it’s accompanied by a dramatic rise in startup valuations. Advocating for a smaller VC ecosystem likely means advocating for smaller startup valuations—and slower economic growth. That may explain why Garry Tan recently said on a podcast: “VC can—and should—be 10x bigger than it is today.” True, if competition vanished and a single LP or GP became “the only player,” that might benefit them individually. But more VC—more capital, more support, more ambition—is unequivocally better for founders and for the world.

To further illustrate this, consider a thought experiment. First: do you think the world should have far more founders than it does today?

Second: if we suddenly had far more founders, what kind of institution would best serve them?

We won’t dwell long on the first question—if you’re reading this, you likely already agree the answer is obviously yes. We won’t belabor why founders are exceptional and essential. Great founders build great companies. Great companies build new products that improve the world, organize our collective energy and risk appetite toward productive ends, and generate disproportionate new enterprise value and exciting jobs. And we certainly haven’t reached equilibrium—where everyone capable of founding a great company already has. That’s why more VC helps unlock more growth in the startup ecosystem.

The second question is more interesting. If we woke up tomorrow with 10x—or 100x—more entrepreneurs (spoiler: it’s happening), what should the world’s venture institutions look like? How should VCs evolve in a more competitive world?

Win the Deal—Don’t Just Go All-In

Marc Andreessen loves telling the story of a famous VC who described the VC game as akin to a conveyor-belt sushi restaurant: “A thousand startups rotate past you—you meet them. Occasionally, you reach out, grab one off the belt, and invest.”

The VC Marc describes—well, for most of the past few decades, nearly every VC operated this way. Back in the 1990s or early 2000s, winning deals really was that easy. Hence, for a great VC, the only truly critical skill was judgment: distinguishing great companies from bad ones.

Many VCs still operate this way—essentially identical to how VCs operated in 1995. Yet beneath their feet, the world has transformed utterly.

Winning deals used to be easy—like grabbing sushi off a conveyor belt. Now it’s extremely hard. People sometimes describe VC as poker: knowing when to pick a company, what price to pay, etc. But that analogy obscures the full-scale war you must wage to earn the right to invest in the best companies. Old-school VCs pine for the days when they were “the only player” and could dictate terms to founders. But today there are thousands of VC firms—and founders have easier access to term sheets than ever. So increasingly, the best deals involve ferocious competition.

The paradigm shift is this: Deal-winning ability is becoming as important—or even more important—than picking the right company. What good is picking the right deal if you can’t get in? Several things drove this change. First, the explosion in VC firms means VCs must compete fiercely with each other to win deals. With more companies competing for talent, customers, and market share than ever, top founders need powerful institutional partners to help them win. They need firms with resources, networks, and infrastructure to give their portfolio companies an edge.

Second, because companies stay private longer, investors can make later-stage investments—when companies are more validated, making competition fiercer—yet still achieve VC-style returns.

Third—and least obvious—is that picking has become slightly easier. The VC market has become more efficient. On one hand, more repeat founders are consistently building iconic companies. If Elon Musk, Sam Altman, Palmer Luckey, or a brilliant repeat founder starts a company, VCs rush to line up. On the other, companies reach hyper-scale faster (with longer private lifespans and greater upside), reducing PMF (product-market fit) risk relative to the past. Finally, with so many great firms today, founders find it far easier to connect with investors—making it hard to find deals other firms aren’t pursuing. Picking remains central to the game—selecting durable companies at the right price—but it’s no longer the overwhelmingly dominant factor.

Ben Horowitz hypothesizes that repeatedly winning deals automatically makes you a top-tier firm: because if you can win, the best deals come to you. You only earn the right to pick once you can win any deal. You might miss the perfect one—but at least you get the chance. Of course, if your firm repeatedly wins the best deals, you’ll attract the best pickers to join you—because they want access to the best companies. (As Martin Casado told Matt Bornstein when recruiting him to a16z: “Come here to win deals—not lose them.”) So winning ability creates a virtuous cycle that elevates your picking ability.

For these reasons, the rules have changed. My partner David Haber describes the transformation VC must undergo in response, in his piece: “Firm > Fund.”

In my definition, a “fund” has one objective function: “How do I generate the most carry with the fewest people, in the shortest time?” A “firm,” by contrast, has two objectives: delivering exceptional returns—and, equally intriguingly, “How do I build a compounding source of competitive advantage?”

The best firms will reinvest their management fees into strengthening their moats.

How Can You Help?

I entered venture capital a decade ago—and quickly noticed Y Combinator played a different game than most. YC secured favorable terms from outstanding companies at scale—and seemed to serve them at scale, too. Compared to YC, many other VCs played a commoditized game. I’d attend Demo Day thinking: “I’m at the table—but YC is the house.” We were all happy to be there, but YC was happiest of all.

I soon realized YC had a moat. It enjoyed strong positive network effects. It possessed structural advantages. People used to say VC firms couldn’t have moats or unfair advantages—after all, they’re “just providing capital.” But YC clearly did.

That’s why YC remained powerful even as it scaled. Critics disliked YC’s scaling; they predicted its demise, claiming it lacked soul. For the past decade, people have forecast YC’s death. It hasn’t happened. During that time, they replaced their entire partner team—and death still didn’t arrive. A moat is a moat. Like the companies they back, scaled VCs possess moats beyond brand alone.

Then I realized I didn’t want to play the commoditized VC game—so I co-founded my own firm, plus other strategic assets. These assets proved highly valuable and generated strong deal flow—so I tasted the differentiated game. Around the same time, I watched another firm build its own moat: a16z. So when the chance to join a16z arose a few years later, I knew I had to seize it.

If you believe in venture capital as an industry, you—almost by definition—believe in power laws. But if you truly believe the VC game is governed by power law dynamics, then you should believe VC itself follows a power law. Top founders will cluster around the institutions best positioned to decisively help them win. Top returns will concentrate in those institutions. Capital will follow.

For founders building the next iconic company, scaled VCs offer an incredibly compelling product. They provide deep expertise and full-stack support for everything fast-scaling companies need—hiring, GTM strategy, legal, finance, PR, government relations. They provide sufficient capital to truly reach your destination—not forcing you to penny-pinch while facing well-funded competitors. They offer massive reach—introducing you to everyone you need to know in business and government, connecting you with every major Fortune 500 CEO and world leader. They grant access to 100x talent—a global network of tens of thousands of top engineers, executives, and operators, ready to join your company when needed. And they’re everywhere—for the most ambitious founders, that means anywhere.

Meanwhile, for LPs, scaled VCs are an exceptionally attractive product on the most basic, critical question: Are the companies driving the most returns choosing them? The answer is simple: Yes. All the largest companies partner with scaled platforms—often at the earliest stage. Scaled VCs get more swings at those pivotal companies—and more ammunition to convince them to accept investment. This shows up in returns.

Excerpted from Packy’s work: https://www.a16z.news/p/the-power-brokers

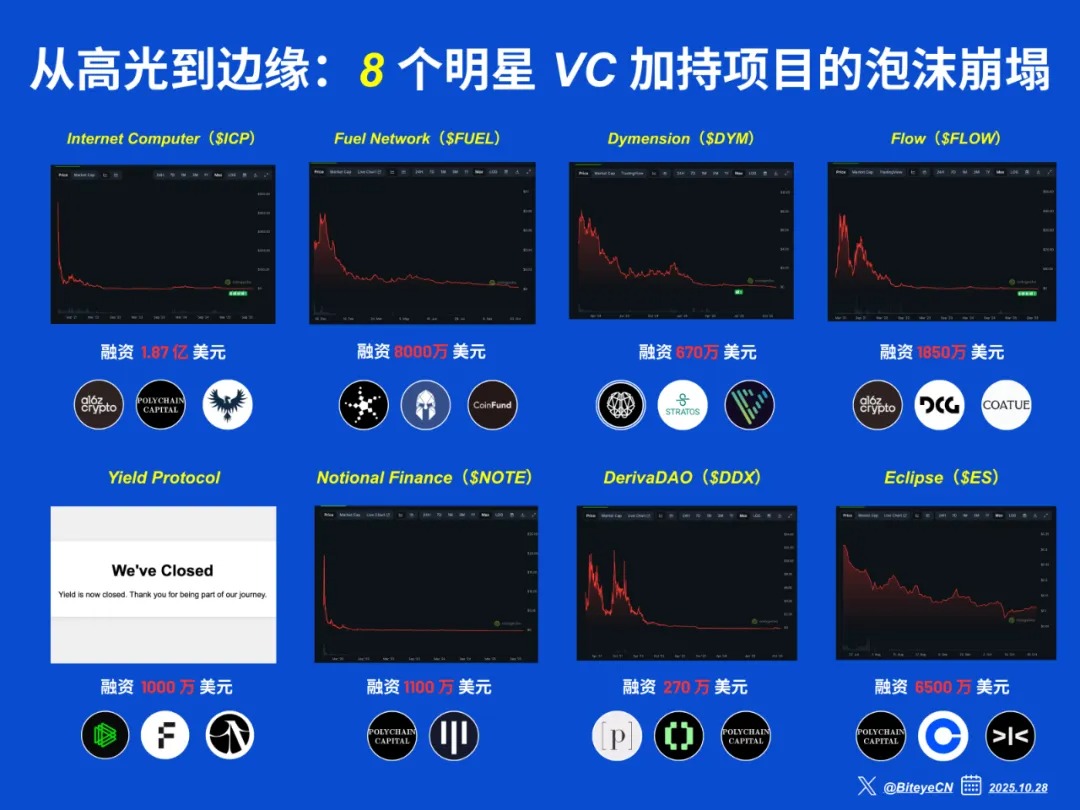

Consider where we stand today. Eight of the world’s ten largest companies are West Coast-based, venture-backed firms. Over the past few years, these companies have driven most of the world’s new enterprise value growth. Meanwhile, the world’s fastest-growing private companies are also predominantly West Coast–based, venture-backed firms—companies born just years ago racing toward trillion-dollar valuations and the largest IPOs in history. The best companies are winning more than ever—and all have scaled institutional backing. Of course, not every scaled firm performs well—I can name some epic blowups—but nearly every great tech company has scaled institutional support behind it.

Go Big—or Go Boutique

I don’t believe the future is solely scaled VCs. Like every domain touched by the internet, VC will become a “barbell”: a few ultra-large players on one end—and many small, specialized firms on the other, each operating within a specific domain and network, often partnering with scaled VCs.

What’s happening in VC mirrors what typically occurs when software eats a service industry. One end features four or five large, vertically integrated service providers; the other end features a long tail of highly differentiated micro-suppliers—whose very existence is enabled by industry disruption. Both ends of the barbell thrive: their strategies are complementary and mutually empowering. We’ve backed hundreds of boutique fund managers outside our firm—and will continue supporting and collaborating closely with them.

Both scaled and boutique firms will thrive—it’s the middle that’s in trouble: funds too large to absorb missing giant winners, yet too small to compete structurally with larger institutions offering superior founder-facing products. a16z’s uniqueness lies in straddling both ends of the barbell—it functions as a set of specialized boutiques, while benefiting from a unified, scaled platform team.

The institutions best equipped to partner with founders will win. That might mean massive standby capital, unprecedented reach, or a vast complementary service platform. Or it might mean irreplicable expertise, elite advisory services, or sheer, unbelievable risk tolerance.

There’s an old joke in VC: VCs believe every product can be improved, every great technology scaled, every industry disrupted—except their own.

In truth, many VCs dislike the rise of scaled VCs outright. They believe scaling sacrifices soul. Some claim Silicon Valley has become too commercialized—not the haven for misfits it once was. (Anyone claiming tech lacks misfits hasn’t attended a San Francisco tech party—or listened to the MOTS podcast.) Others resort to self-serving narratives—calling change “hubris against the game”—while ignoring that the game has always existed to serve founders. Of course, they’d never voice similar concerns about the companies they back—whose very existence rests on achieving massive scale and rewriting industry rules.

Saying scaled VCs aren’t “real venture capital” is like saying NBA teams shooting more threes aren’t playing “real basketball.” Maybe you don’t think so—but the old rules no longer dominate. The world has changed, and a new model has emerged. Ironically, the way the rules change here mirrors exactly how the startups VC backs transform their industries. When technology disrupts an industry—and a new cohort of scaled players emerges—something is always lost in the process. But far more is gained. VCs intimately understand this tradeoff—they’ve spent decades backing it. The disruptive process VCs want to see in startups applies equally to venture capital itself. Software ate the world—and it won’t stop at VC.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News